Spinning the radio dials like mini roulette wheels was, in 1993, the best way to discover new music. Static, a snatch of a familiar song, a news report, then ah wait that sounds interesting. You’d walk into a record store with that song stuck in your head, and with any luck would walk out after a conversation with the clerk a few tapes richer, a few dozen dollars poorer.

One year later, everything had changed. For in 1994, the best way to discover new music was to email an AI.

“This sounds ****in’ moronic,” said one Dave Dell in response to the idea, convinced his love of Lustmord meant the AI couldn’t possibly match his tastes. Even he acquiesced: “I'll try it anyways.”

By the time The Cranberries released their hit single “Zombie” that September, over two thousand Daves had tried their luck, emailing Ringo with their favorite artists. To their surprise, they’d get a reply from what appeared to be early artificial intelligence, filled with recommendations of new music they’d love. Enough that, seven years later, science fiction writer Cory Doctorow would reminisce that “half the music in my collection came out of Ringo,” that nascent music AI.

Yet incredibly, Ringo was little more than those couple thousand users’ recommendations, averaged and redistributed via email. An email that users would quickly come to think of as a human, a friend, one in a quick succession of email-powered crowdsourced recommendation AIs.

The surprising wisdom of the crowds

It all started with what MIT assistant professor Paul Resnick called “A deceptively simple idea,” in 1994.

“People who agreed in the past are likely to agree again,” he postulated, an idea that’d been christened Social Filtering by MIT Thomas Malone seven years earlier. If you and another person both like the same song, or book, or author, there’s a pretty good chance that if one of you likes a new artist, the other will like it as well. The more overlapping agreements you have, the better one’s tastes should be predictive of another’s.

And, maybe, social filtering could be an organizing principle of the internet.

For as the nascent world wide web grew exponentially from a single website in 1991 and ten in 1992 to 623 sites in 1993 and over 10,000 by the end of 1994, the ancient prophecy that “knowledge shall increase” suddenly seemed more an omen of content overload than a portent of good things. Cataloguing and categorization could only go so far. It would be easy enough to find another Cranberries album once you knew you liked them. Finding the next new band that you’d love required something beyond lists. What good was infinite knowledge and limitless content without a way to discover it?

“The exploding volume of digital information makes it difficult for the user, equipped with only search capability, to keep up with the fast pace of information generation,” wrote Stanford’s Tak W. Yan and Hector Garcia-Molina, in their stab at solving the same problem. “There is a need for technology to help us wade through all the information to find the items we really want and need, and to rid us of the things we do not want to be bothered with,” as MIT Media Lab’s Upendra Shardanand summarized the issue.

Maybe the best option would be to ask someone else. We like getting recommendations from others, after all. “Choice under uncertainty is an opportunity to benefit from other more knowledgeable people,” wrote a Bellcore research team of their stab at the same problem in 1993.

Social filtering, teams from Xerox and Bell, Stanford and MIT alike agreed, seemed the perfect discovery mechanism of the future. That is, if they could gather everyone’s preferences and turn them into predictions accurately.

Email as the universal interface

The idea behind Tapestry’s social filtering

Decades before the explosion of email newsletters, newsgroups were filling up early inboxes at a time when hard drives cost as much as $4,000 per gigabyte. Storage wasn’t the only scarce resource; no one had time to read every rant and reply in their inboxes.

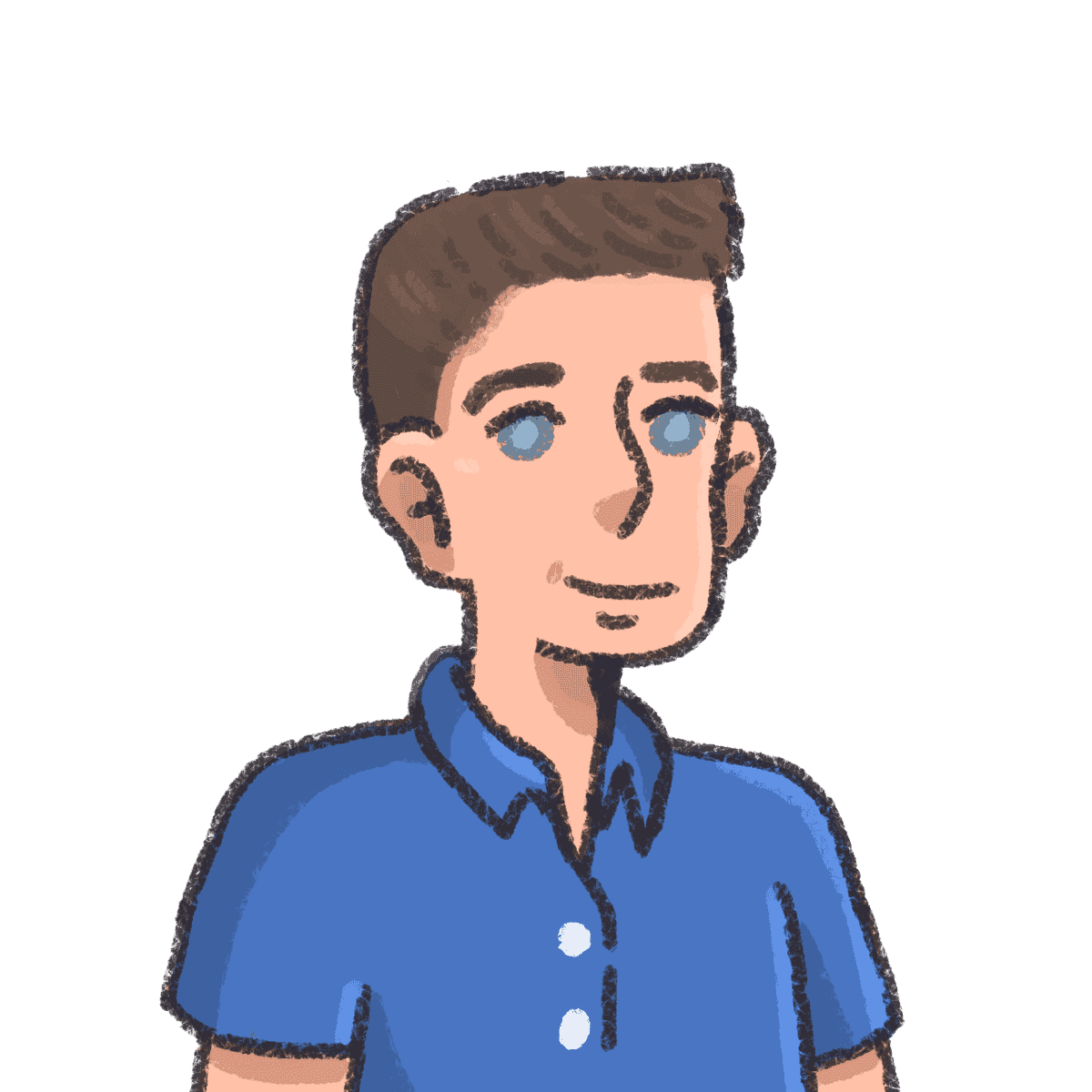

Automatic filters were too restrictive—and they weren’t intelligent. Intelligence was when a friend read a message that hit the spot, and forwarded it on to you. It was when a colleague deleted a message, a silent vote that others might also deem that message irrelevant, or when they saved or replied to was a message in a vote towards its relevance.

Therein lay an idea: “More effective filtering can be done by involving humans in the filtering process,” postulated David Goldberg, David Nichols, Brian Oki, and Douglas Terry of the Xerox PARC team. That, in 1992, was the insight behind Tapestry, a short-lived collaborative email app inside Xerox PARC.

Tapestry sorted newsgroup emails with ratings. When you read an email or other document that you liked, you’d add an endorsement that Tapestry would store in a database alongside others’ endorsements. The next time someone searched for a message or document, they’d first see the messages that had the most endorsements, or could filter by specific users’ endorsements to follow the likes of a particular tastemaker.

“Eager readers will read all the documents ... in order to get immediate access,” the team surmised, while “more casual readers will wait for the eager readers to annotate, and read documents based on their reviews.”

SIFT’s social filtering model

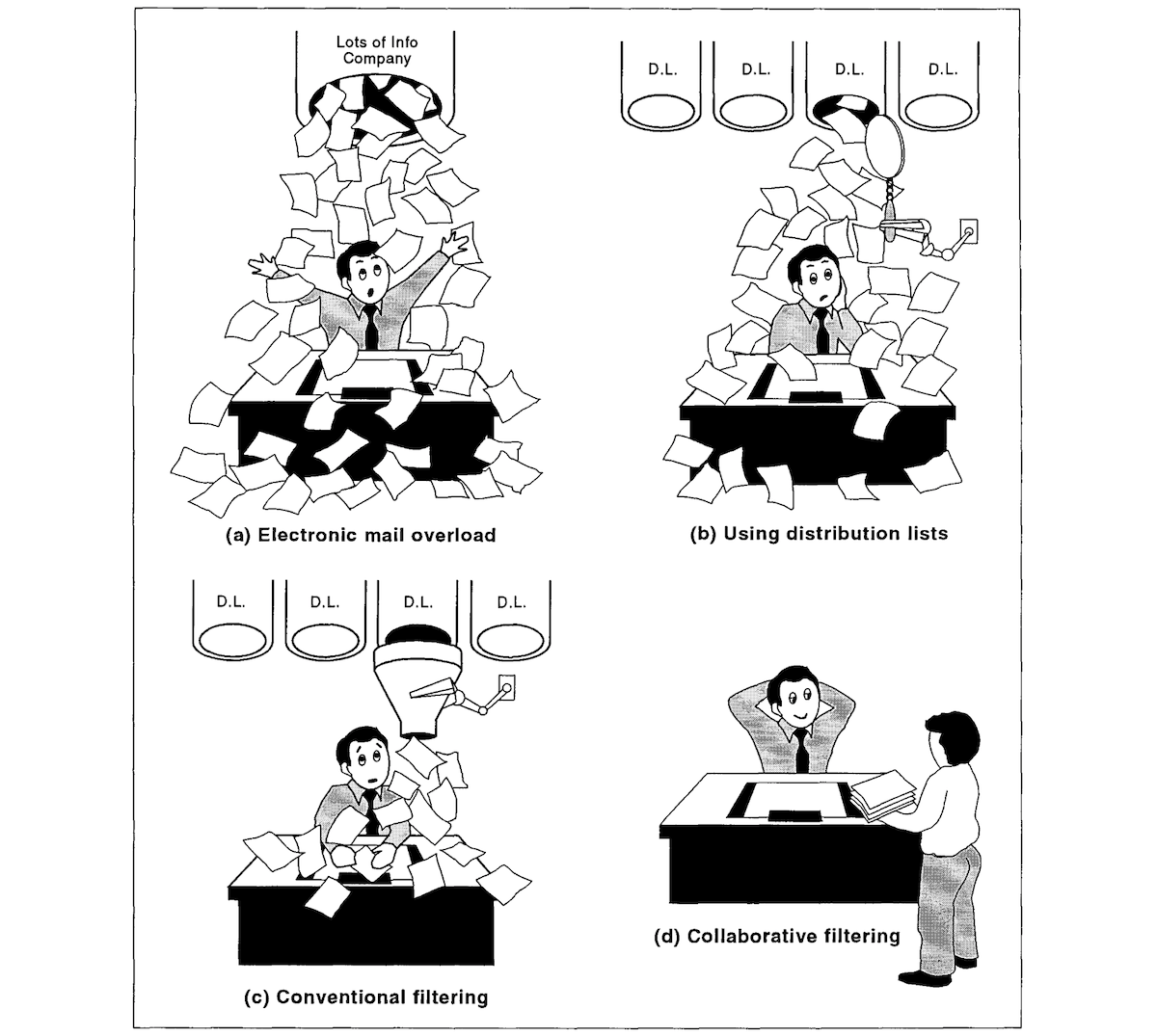

Tapestry, it seems, never left Xerox’ bounds. But two years later, in February 1994, a Stanford team took up the mantle with SIFT, or Stanford Information Filtering Tool. It, too, sorted through messages based on crowdsourced wisdom. But it didn’t require a new app. SIFT, instead, was built around email.

“Email communications is the lowest common denominator of network connectivity,” wrote the team. “By having an email interface, a SIFT server is accessible from users with less powerful machines, with limited network capability, or behind Internet-access firewalls,” features that, to this day, make email one of the most universally accessible bits of the internet, even behind corporate firewalls and government censorships.

A SIFT email preview in an early browser

SIFT put email front and center. You’d sign up with an early web form and choose a topic of interest, like “underwater archeology.” SIFT would then regularly email you a list of articles and their first few lines to see what piqued your interest—an early curated email newsletter of top headlines. You’d then reply again with the articles you wanted to read, and SIFT would both email you the full messages, and store your choices as votes to help it refine what it’d recommend next time.

SIFT had some hits and some misses, and users were surprisingly accepting when things went wrong. “Well, nothing is perfect,” surmised Jiří Peterka in an early review. But SIFT clearly hit a nerve. “Within ten days of the announcement, we received well over a thousand profiles,” reported the team. By November, ten months after launch, SIFT was matching 45,000 articles each week to over 13,000 subscribers’ profiles.

Movies by email

Meanwhile, on opposite coasts, a Bell team was pondering decision paralysis. “Future users of the national information infrastructure will be overwhelmed with choices,” wrote Bellcore researchers Will Hill, Larry Stead, Mark Rosenstein and George Furnas in their 1995 writeup of the project. The best way out was to ask an expert, they decided. “When making a choice in the absence of decisive first-hand knowledge, choosing as other like-minded, similarly-situated people have successfully chosen in the past is a good strategy.”

So a team from the same Bell roots as UNIX and C++ and the transistor itself decided to harness social filtering to help you figure out which movie to rent from Blockbuster.

Movies lent themselves well to the model. There were a limited number of movies to sort and recommend, and existing expert ratings from the likes of Roger Ebert to pre-seed the database. If people would share their favorite movies, the system could match them with others who liked the same movies, and recommend other movies those people liked.

And it all ran over email.

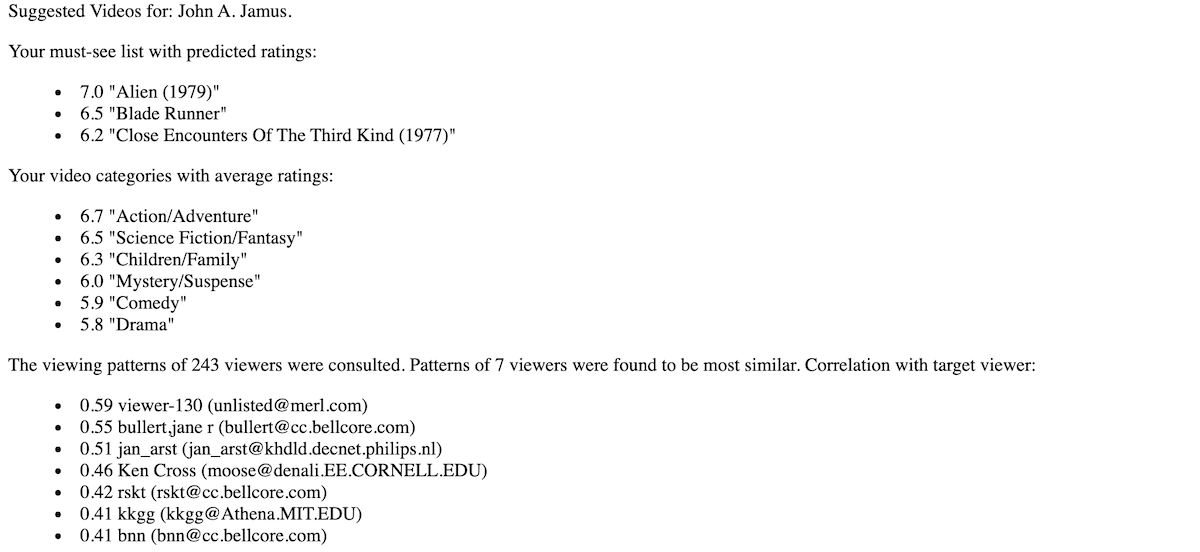

An example videos@bellcore.com email

“The Internet email interface is currently a subject-line command interface,” the team wrote. For a few short months, from October 1993 to May 1994, you could email the subject “ratings” to videos@bellcore.com, and receive a reply with an overwhelming 500 movies.

Reply with your reviews of the movies you’d watched on a 1 to 10 scale, and Bellcore’s server would parse your reply and add your ratings to a database. Then, it’d look for “correlations between the new user's ratings and ratings from a random subsample of known users,” then “evaluate every unseen movie, sort them by highest prediction and skim off the top to recommend.”

Minutes later, you’d get back a reply, recommending you watch Alien and Blade Runner, say, along with a list of people who shared your tastes. It was a recommendation engine and nascent social network in one, where you just might find your next favorite movie and make a friend.

“Virtual communities may also sprout up around other domains such as music, books and catalog products,” predicted the team.

A musical mirror

It didn’t take long. Two months after videos@bellcore.com shut down, a new MIT project launched: Ringo. “Our system, in our opinion, tackled the much more difficult problem domain of music,” wrote co-founder Upendra Shardanand in his master’s thesis.

The ingredients were in place. Social filtering had been proven out by Tapestry and SIFT. “The user interface for videos@bellcore.com system was used as a reference when designing the e-mail interface for Ringo,” said Shardanand. Along with that, Ringo added email-based accounts to learn from your preferences over time, and a constrained Pearson Correlation algorithm to rate “commonality between two users when computing the weights ... proportional to the number of artists both users have rated in common.”

That, and a personality. Ringo’s original emails were written as if they came from a person, such as “I recommend that you check out these artists...” It got toned down over time, partly to ensure people sent clear, precise instructions that Ringo could understand instead of fluent, natural language—but it quickly became clear that people thought of Ringo as a friend.

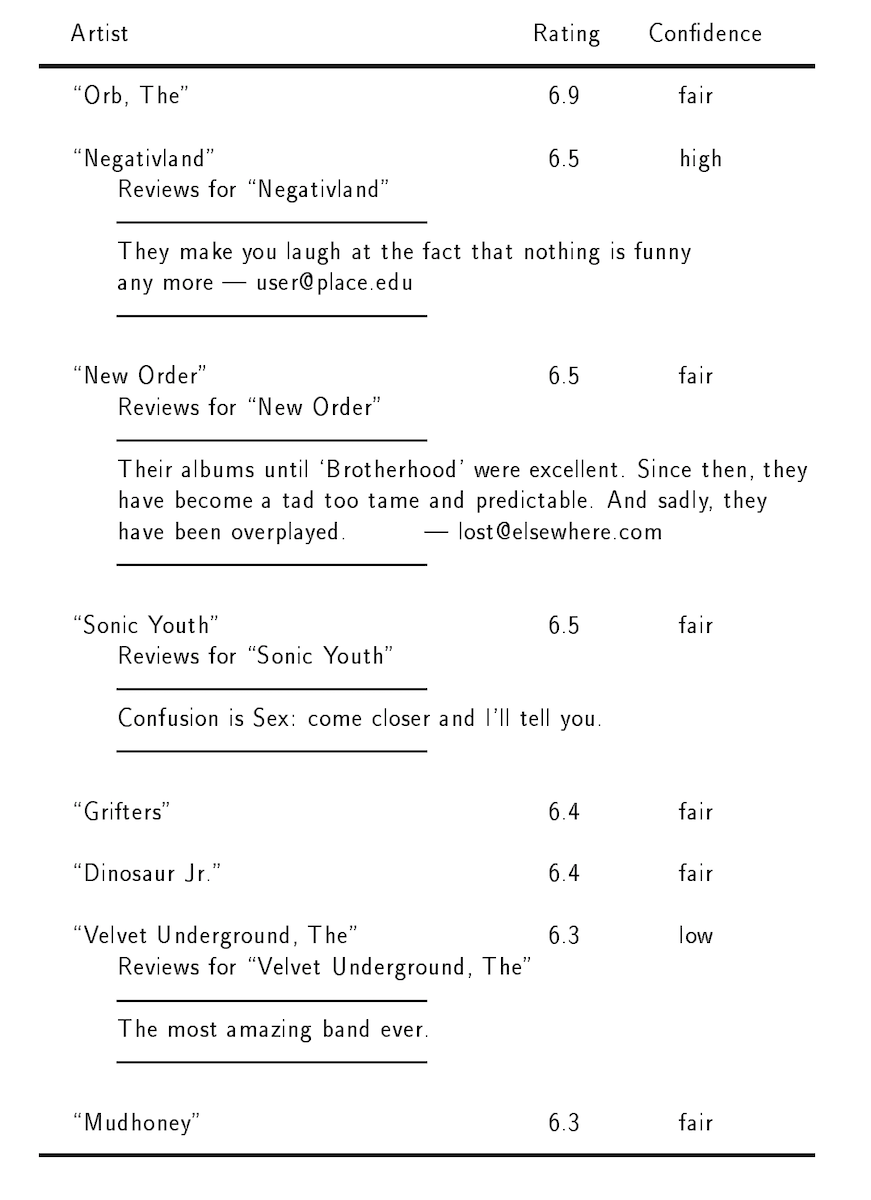

You’d email Ringo to sign up, and it’d reply with a more manageable list of 125 artists that you’d rate from 1 (“Pass the earplugs,” in Ringo’s description of its lowest rating) to 7 (“BOOM! One of my FAVORITE few!”). Ringo would then match your favorites to others with similar tastes, and reply with the eight artists it thought you’d like most.

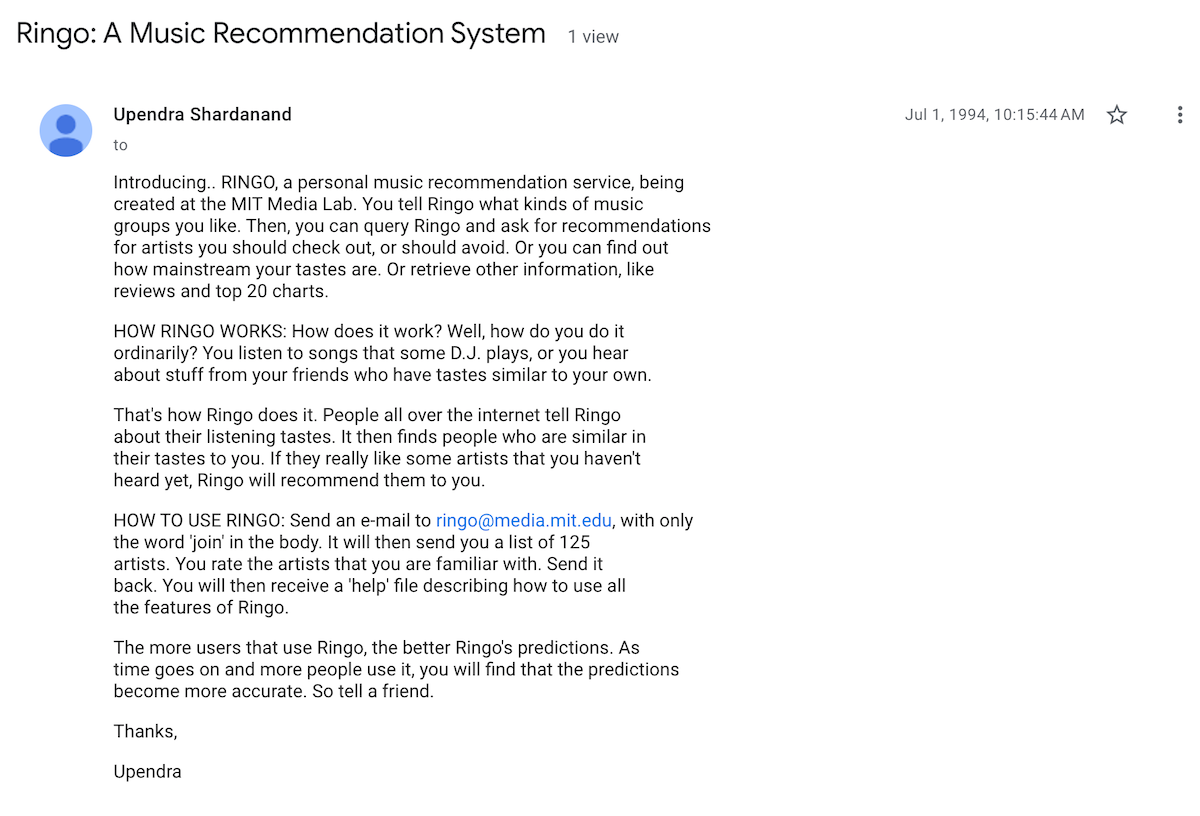

The first email promoting Ringo, on a USENET group

On July 1, 1994—four years and 11 months before Napster’s launch—Ringo opened its inbox to the world. Shardanand marketed it on USENET groups. “The more users that use Ringo, the better Ringo's predictions,” he wrote, “so tell a friend.” Soon enough, Ringo was spreading by word-of-mouth in early email newsletters and other Usenet groups.

It worked—but it wasn’t always right. “In the first couple weeks of Ringo’s life, Ringo was relatively incompetent,” Shardanand recalled, and yet that, somehow, didn’t dampen people’s enthusiasm for the email bot they quickly came to love.

Example Ringo artist suggestions

“People would see the suggestions, and say things like ‘That one’s about right, that’s right, well that one I’d probably rate lower, but wow, it’s working,’” he recalled. “I watched them score artists, then I saw the poor suggestions, and was thinking, ‘You’ve got to be kidding.’ It’s as if they expected it [to] work, and therefore it did.”

Even when it came back with no recommendations, people were impressed. “It said there weren't enough participants out there like me,” Pat Anders recalled months after Ringo’s launch. “I was flattered.”

Others, though, found magic in the recommendations. “RINGO always came up with a great selection,” said Joe Morris. “I got turned on to a bunch of stuff I would of never found otherwise.” As did Cory Doctorow, with a music library still years later influenced by Ringo’s recommendations.

For it wasn’t simple recommendations over email. It was trust in a system that seemed greater than the sum of its parts. “A fellow Media Labber commented that possibly it is because people see Ringo’s suggestions as a ‘reflection of themselves,’” said Shardanand. “Once you have decided that there must be a logical connection between what you have told the system about your tastes and the system’s recommendations, then you are much more inclined to believe the predictions to be right.”

AI is people

“I am largely of the opinion that great AI consists of aggregated human decisions, not machine generated decisions,” said Cory Doctorow, reminiscing about Ringo’s music recommendations.

For in every take on email-powered social filtering, the secret ingredient wasn’t the interface, nor was it the algorithm. It was in the crowdsourced data, and the system’s ability to match you with others of similar taste.

Some folks defied classification, felt that AI recommendations would devalue their unique tastes. Others embraced the crowdsourced models, found comfort in peeking in an AI-filtered mirror.

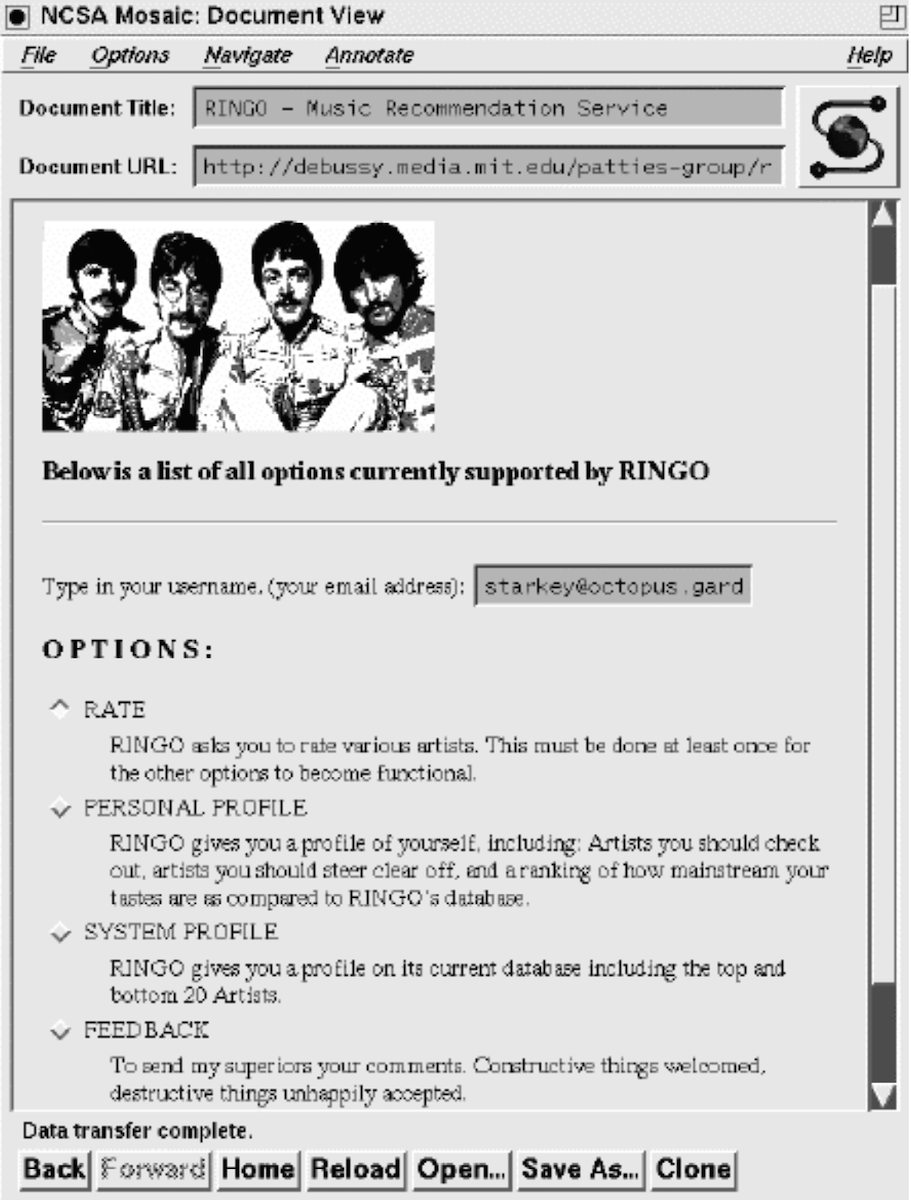

An early web form to sign up for Ringo

The services themselves faded with time. SIFT grew into a commercial project that sold ads for early newsletters, while the Stanford Library Project itself later provided the primary funding for Larry Page and Sergey Brin as they developed the ideas behind PageRank that turned into Google search (itself another way to harness the wisdom of the crowds).

Ringo later launched on the web first as HOMR (Helpful Online Music Service) then as Firefly (a community website for collaborative filtering that, fun fact, pitched RSS-competitor ICE to Microsoft), and won second place in MIT’s 1995 student business competition. The magic faded as it left email behind, though, and when Microsoft acquired it for $40 million in 1998, the only thing the software giant kept was their email-based login that, over time, morphed into Microsoft Passport.

31 years after those early crowdsourced email tools provided people’s first interactions with AI, today’s GPTs are eerily reminiscent of both those early app’s crowdsourced wisdom, and of our credulity to seemingly intelligent agents that mirror our preferences. The social filtering lives on, in ever less personal ways, in Google’s PageRank, Facebook’s feed algorithm, Netflix’s suggestions, and Spotify’s Daily Mix playlists.

And, in a roundabout way, email newsletters’ staying power may be due to the same selection bias and sorting powers that inspired social filtering-powered software. If you read something you like, there’s a fair chance you’ll continue to like the other things that person writes. Newsletters are the easiest way to select into that author’s filter bubble and find new things you like from their recommendations.

“As the information barrage continues to accelerate, agents will be as indispensable as E-mail,” predicted Ringo’s Shardanand in a foreshadowing of today’s AI and MCP servers and agents. People, it turned out though, were what was indispensable to email and recommendations you’d love.