People like to tell the story of how VHS beat Betamax because adult film studios backed VHS. It’s a clutch-your-pearls story that says nothing about why these multi-million-dollar businesses picked one format over the other. The real story is that while Betamax tapes had better resolution and fidelity, VHS was cheaper, offered longer recordings, and, most importantly, was the more open format.

Not many people talk about how or why RSS won the content syndication war because few people are aware that a war ever took place. Everyone was so fixated on the drama over RSS’s competing standards (Atom vs RSS 2.0) that they barely registered the rise and fall of the Information and Content Exchange (ICE) specification, which had been created, funded, and eventually abandoned by Microsoft, Adobe, CNET, and other household names.

ICE was the Betamax to RSS’s VHS. The Information and Content Exchange standard was more advanced, more expensive, less open, and unable to counter the overwhelming number of bloggers who flooded the market with DIY-friendly RSS feeds.

The dawn of war over syndication

When Pew Research informally asked readers about online activities that had lost their charm, most of the responses mentioned surfing the web, something people used to do for the hell of it, just to see what was out there. That was in 2007, the same year the iPhone launched, long before most of us were addicted to social feeds. One user complained that “the net is no longer a toy but more like a Velveteen Rabbit — while some loved parts have worn away or disappeared, other parts are still in place.” People hadn’t lost interest in surfing so much as the waves of content had grown to crushing heights.

Big-name publishers got a whiff of monetization and became obsessed with content syndication. They figured that if they could make it easier for websites to repackage and republish their articles and eCommerce catalogs, corporate content creators wouldn’t need to worry about declining traffic to their sites. They could simply make a deal with whichever site was currently in vogue.

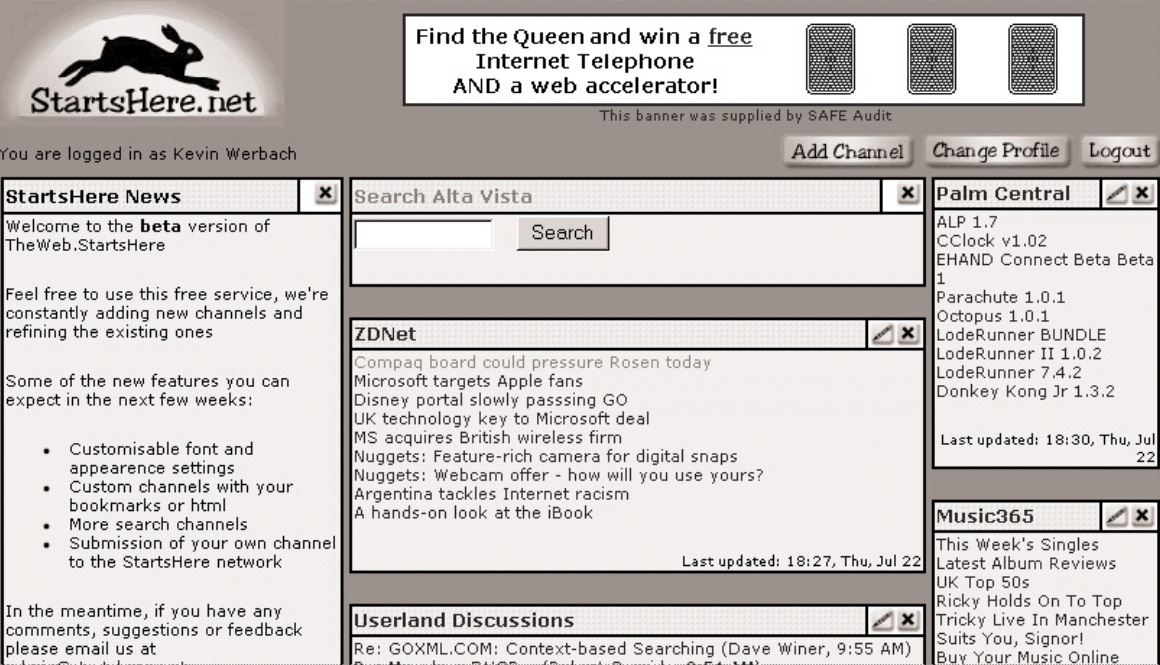

“Syndication will evolve into the core model for the Internet economy, allowing businesses and individuals to retain control over their online personae while enjoying the benefits of massive scale and scope,” Kevin Werbach wrote in the July ‘99 issue of Release 1.0. “The foundations for pervasive Web-based syndication are now being laid.”

The first attempt came in the form of the Information and Content Exchange (ICE) standard, which, like Betamax, predated its archrival by almost exactly a year. ICE’s stated goal in a March 1998 proposal was to standardize how data posted to one website could be automatically published on other websites. It was unapologetically commercial from day one, promising to “expand publishers’ electronic sales by making it easier to license the same material to multiple sources.”

The My Netscape Network port via Scripting News

RSS entered the game as a humble widget on the experimental My Netscape Network portal. Any website owner who used Netscape’s nascent XML-adjacent tags to create a feed of their website’s updates could have said feed added to Netscape’s list of 600+ “channels”. When a user picked a channel from the list, it added a widget to their personalized My Netscape Network page, aggregating their favorite blogs and news sites on a single page.

ICE and RSS had a lot in common. Both used XML to create a common language between syndicators and subscribers. Both used self-describing tags to differentiate content elements. And both let subscribers “pull” the latest feed at any time. Philosophically, though, they couldn’t have been further apart.

Revenue vs readership

One of the creators of ICE was Vignette, famous for its StoryBuilder content management software. They ceded technical development to a consortium that included Microsoft, Adobe, Reuters, and others, while focusing on commercial development. In 1999, Vignette invested $14 million in the iSyndicate platform in exchange for iSyndicate moving exclusively to ICE, while shopping around their proprietary ICE server–priced at $50,000–to other publishers.

The first desktop RSS aggregator via Internet Archive

Meanwhile, RSS was sprinting in the opposite direction. Headline Viewer was released in April 1999 as a free desktop feed aggregator that promised to let users “Watch mailing lists! Watch weblogs! Be cool!” It was soon followed by the first web-based aggregator at my.userland.com. There wasn’t a whiff of server racks or five-figure investments. In fact, there wasn’t even anyone at the helm, as Netscape had abandoned development.

“Now, let the flames begin…repeated attempts to find anyone who cares about RSS at Netscape have turned up nothing,” Dave Winer ranted on his blog in the summer of 2000. “The people we worked with at Netscape left shortly after [version] 0.91 was finalized.” That would have immediately killed the consortium-driven ICE standard. Not so for RSS’s grassroots efforts. Winer simply wrote his own version.

“Up until this morning I wasn't sure if this document should be called 0.91 or 0.92. I was concerned that practice had deviated from the Netscape spec, esp in respecting the limits it imposes, which most developers (myself included) think are ridiculous and unweblike…so I changed the title from 0.92 to 0.91. So all this is a cleanup. All the Netscapeisms are removed.”

What started as a passion project by a disgruntled individual grew into a movement. And those in the ICE camp knew it. Laird Popkin went as far as writing a post about how to map RSS into ICE syntax, pointing out that “The widespread adoption of RSS by low-end syndicators to distribute promotional links should serve as a clear indicator of the importance of this scenario in the world of syndication.”

Complicated vs Uncomplicated

But there was simply no getting around how bloated ICE’s requirements were. Its North Star was automating complex, corporate publishing partnerships. It contained fields for catalog pricing and negotiation, content expiration tags, copyright enforcement functions, and the ability to apply the display website’s visual branding to feed content. While most of them could be ignored, that didn’t make its 58,000-word Getting-Started guide any more digestible.

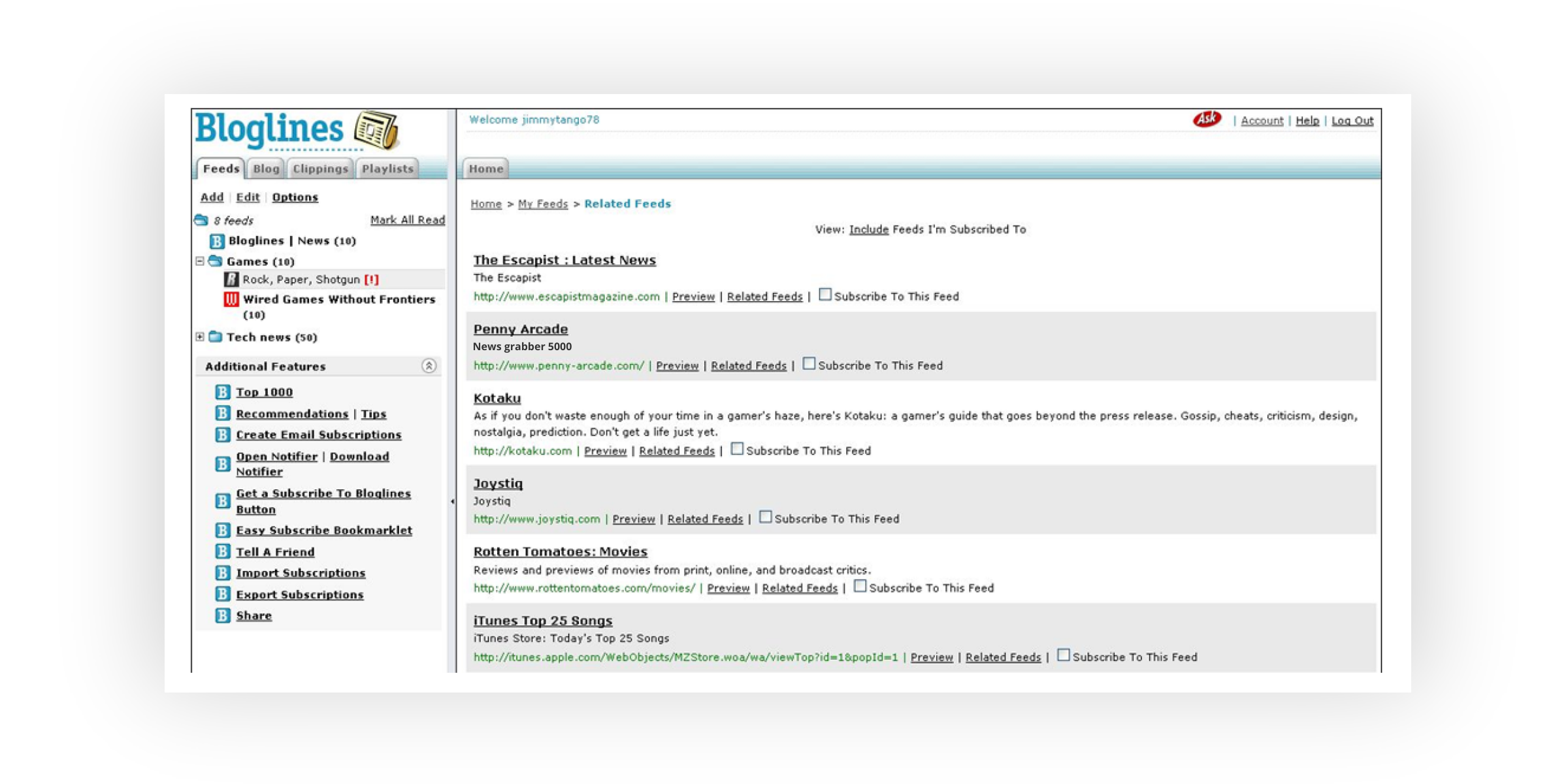

A web-based aggregator in 1999 via Release 1.0

Werbach predicted in The Web Goes Into Syndication that, because ICE was overkill for most uses, “Should this become a head-to-head competition, though, the moral of the Internet’s story is that simple, open-source protocols that scale up tend to win over complex top-down approaches.”

Almost anyone could set up an RSS feed or an RSS aggregator. When Winer released RSS version 2.0 in 2002, a feed could be considered compliant with only three elements: feed title, feed description, and a link to the items you wanted to share. “I definitely want ICE-like stuff in RSS2, publish and subscribe is at the top of my list, but I am going to fight tooth and nail for simplicity.” Winer argued in one of the many combative and public RSS mailing lists.

Never mind that the RSS group couldn’t even agree on what the acronym stood for, they were trouncing ICE. The New York Times, a publisher that should have been firmly in ICE’s wheelhouse, adopted RSS in November 2002. ICE limped on, however, with the authoring group releasing version 2.0 in 2004.

But less than a year later, Microsoft, arguably ICE’s biggest cheerleader, had a dedicated RSS blog. Its first post proposed icon designs for Internet Explorer’s built-in RSS features. It wasn’t an explicit capitulation. ICE and RSS could have theoretically co-existed. Just like Betamax could have let other companies manufacture and sell Betamax players. But they didn’t. So they lost.

When small wins are better than big ones

In their timeline of The Rise and Demise of RSS, Sinclair Target sees the glass half empty, believing that in another timeline the standard could have been more widely adopted if not for the fights between developers. “RSS, an open format, didn’t give technology companies the control over data and eyeballs that they needed to sell ads, so they did not support it. But the more mundane reason is that centralized silos are just easier to design than common standards.”

And yet, no one has heard of ICE. I couldn’t even find proof of any publishers who used it to ink syndication deals. RSS, meanwhile, lives on. RSS-to-email is one of Buttondown’s most popular features!

"I can't really explain it, I would have thought given all the abuse it's taken over the years that it would be stumbling a lot worse," Winer told Wired in 2015, as opinions on algorithmic social media began to sour.

All RSS had to do to weather ICE, Twitter, AI, and whatever comes next, was keep things simple and let users build their own feeds, filters, lists, and aggregators. Like email, it probably won’t make anyone a billion dollars or reshape entire industries. But it will always be wholly yours. And if that isn’t nice I don’t know what is.

Header image via Bloglines.softonic.com