There’s a single story I can picture from the binder in my childhood kitchen: A printout of a forwarded email. Neiman Marcus, it claimed, had overcharged someone to the tune of $250 for a cookie recipe, and the indignant writer got their revenge by sharing the cookie recipe for free, asking you to join in the cause and spread the recipe far and wide.

I don’t remember ever making the cookies. I’ve a weakness for chocolate chunk cookies, and would inevitably turn to the Troll House recipe instead. But that email printout, with its whiff of intrigue and vigilante justice, beckoned among the clippings, and each time I’d idly wonder if those cookies were worth their price tag.

The tale, of course, was a tall one. The New York Times debunked it in 1997 as the latest mutation in a seven-decades-long game of telephone, starting with a supposed $100 recipe for red velvet cake from the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The ingredients for virality, a fake story that taps into greed, envy, and revenge, were a human, not tech, phenomena.

Then email forwarding lowered the costs of distribution to zero, the story took on a new life, and landed as an email printout in my parents’ kitchen, 8,000 miles away from the nearest Neiman Marcus.

Simpler than copy and paste

Forwarding emails is arguably too easy. If one had to copy the email body and subject into a new email, if indeed they had to do anything that slowed them down, maybe they’d think twice before forwarding a message.

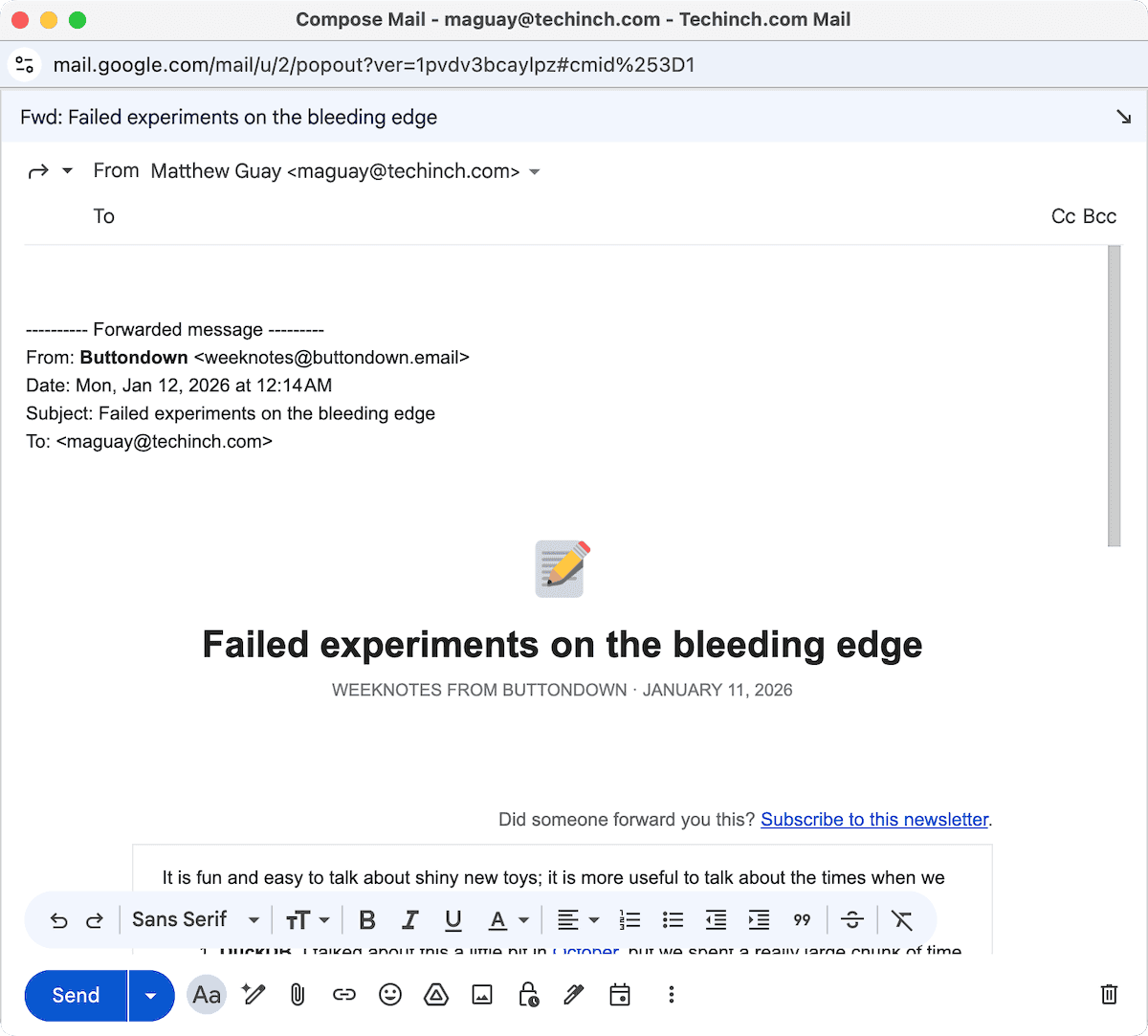

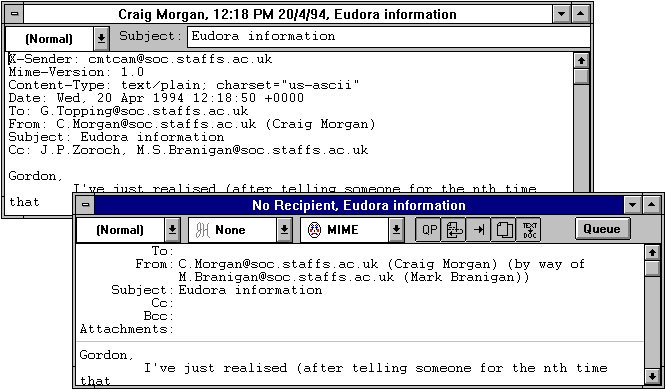

But alas, the forward button does all the work for you, a mistake Twitter would repeat, decades later, by reducing retweet to a single tap. The standard email Forward button, in a single click, prepends the original subject prefaced with Fwd:, copies the original message as an indented quote, and puts the cursor in the To: field.

It’s simplicity by design, works in practice much the same as replying to an email (only there, the sender’s address goes in the To: field, the subject is prepended with Re:, and your cursor starts in the email body). And no wonder: Reply and forward were added to email by the same inventor.

“I was getting, you know, as many as ten emails a day,” remembered John Vittal of his time in 1974 as a UC Irvine grad student, what felt like an overwhelming volume of messages at that time.

The original software to read email messages was, appropriately enough, called READMAIL, let you read email messages in order, one after another, and nothing more. Then came RD, the email software Vittal used, with tools to sort emails and read them in any order you liked.

But “you couldn’t do anything with it,” recalled Vittal. “You couldn't file messages, you couldn't do any of the things that you normally do with email today.” There were forks galore, but none did exactly what he wanted with email. “So I took another fork of the same code,” said Vittal, “and created a program called ‘MSG.’” For message, that is, not monosodium glutamate.

Forwarding emails required copying and pasting the email body, and replies required that along with copying the original sender’s email address. Something that would take a few seconds and clicks on a modern computer, but that was “unpleasant” at best, in Vittal’s words, on a 1970’s-era TENEX terminal.

MSG simplified it down to a single command. “The main innovations were forward and reply, which I called answer at the time,” recalled Vittal. Press F to forward a message, A to reply (or rather, answer), and MSG did all the hard work of copying in the background for you. Suddenly forwarding a message took less work than writing a new email; all you had to do was press f and add a few friends’ email addresses, and you set off a viral email chain.

And it set a precedent. MSG spread, through colleagues, to US military email projects and the XEROX PARC lab where it influenced other early email programs. Today, the f shortcut is still Gmail’s keyboard shortcut to forward messages (and, incredibly, both r and a still works to “answer” or reply to emails in Gmail).

Could you please ~/.forward the mail?

Passing along messages someone might enjoy is one thing. But what if you have an email inbox you no longer use, and want all messages redirected from that account to your new one? Like USPS Form 3575, telling the post office that you’ve moved and asking them to redirect mail to your new location, email needed a way to automatically get rerouted to a new address.

Source routing laid the building blocks. Its detailed email addresses, like @csnet-gateway,@sri-unix.arpa,@mit.edu:bob@mit.edu told your computer to send an email first to this server then that one, an early hack to patch together otherwise incompatible email systems in the days before DNS.

Source routing was standardized in RFC 821. The very next RFC tried to standardize ad hoc email forwarding. “Some systems permit mail recipients to forward a message, retaining the original headers, by adding some new fields,” read RFC 822. “This standard supports such a service, through the ‘Resent-‘ prefix to field names. For example, the ‘Resent-From’, indicates the person that forwarded the message, whereas the ‘From’ field indicates the original author.”

But, through momentum or lack of interest, the resent- fields never were baked into standard email apps’ forwarding. Copying and quoting the old message was enough; no need to standardize everything. That is, when forwarding a one-off email to a friend. Where resent-from headers did find a place is in automatically-forwarded emails.

Their first implementation, in the early terminal email application sendmail, was built around ~/.forward files. Much like symlinked folders or 301 redirects on a website ~/.forward files would include details of your new email address, and when sendmail fetched new messages it’d first check that forward file to see if it had any instructions. If it did, it’d resend the emails along to their ~/.forward location—with, apparently, no changes to the messages themselves, as though they were sent to the new location with no stops in-between.

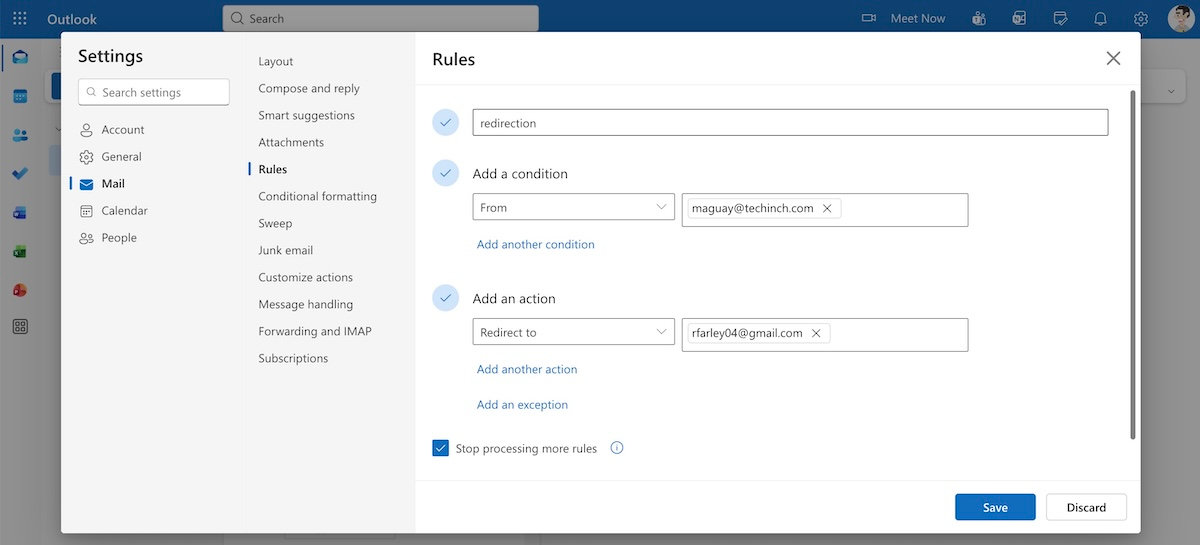

Then came the server-side implementations, and the header fields came into use. I, for one, maintain my high school Hotmail email account, and use it as my default account to sign up for loyalty cards and other things that are likely to send me more junk email than important messages. So I have Outlook.com neé Hotmail auto-forward every message to my primary email account, and those emails are where I found a rare resent-from header lurking. The email was received by Exchange in Outlook.com, then resent from my @live.com email address, and finally received by Gmail's server. The headers revealed the history, with a new Gmail Received: header, a Resent-From: header, and finally the original Received: header showing the origin server.

That, today, is the only time you’re likely to see Resent headers. Later RFCs reflect that more common usage. “The purpose of using resent fields is to have the message appear to the final recipient as if it were sent directly by the original sender, with all of the original fields remaining the same,” says RFC 2822 from 2001, and indeed my Hotmail-to-Gmail emails appear perfectly, as if they originally were sent to my Gmail account. Hotmail’s redirect feature today lets you forward all of your emails from one account to another, or via Rules forward individual emails to other recipients, complete with resent headers. Gmail includes similar features but its auto-forwarded emails use X-Forwarded-For: and X-Forwarded-To: headers. They accomplish the same goal, but without the historic continuity of Outlook neè Hotmail’s approach.

“Not at this address” for email

But what if someone sends you an email intended for someone else? If a letter addressed to the wrong person shows up in your mailbox, you write “Not at this address” on the envelope and give it back to your mail carrier. With email, another twist on forwarding, for a spell, handled the task for you.

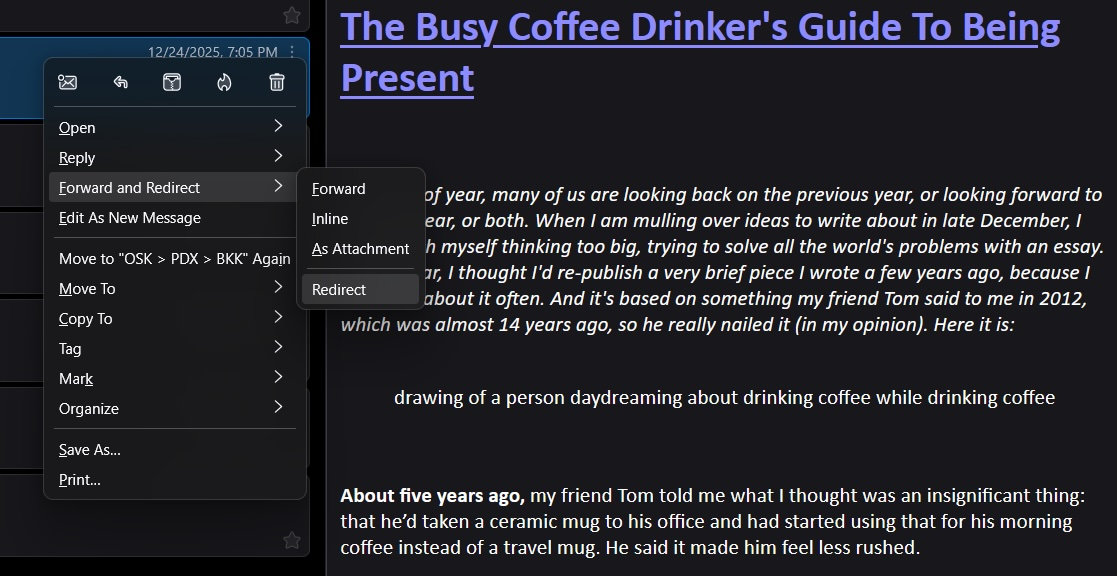

Eudora, the original fan-favorite power-user email app that brought HTML emails, powerful filters, and a customizable user interface into the mainstream, had its own ideas around forwarding emails. Along with traditional forwarding, copying and quoting the message, it included a unique option to redirect a message.

Redirecting a message copied the original message—but did not offset it as quoted text, instead leaving the original message untouched. It set the From: address to list the original sender with your address shown as an intermediary (such as From: bob@email.com (Bob Tester) (by way of j@example.com (John Smith))). You’d type the new recipient’s address, and they’d receive the email message almost exactly as if it’d been originally sent to them. And if they replied, they’d reply to the original sender, whereas in a forwarded email they’d reply to you.

With the demise of Eudora, redirecting messages seemed poised to fade away. And just in time: DMARC, which ensures an email’s From: field’s domain matches the sending domain server, was introduced in 2013, just as Eudora hit end-of-life. An Eudora redirected message would have been more likely to fail DMARC, with the original sender in the From field and your server as the behind-the-scenes sender.

Then in 2021, the Thunderbird email client revived redirecting, with a twist. If you redirect an email, it sends them the full, original email with you as the sender, but with the original email author’s address in the Reply-To: field. That way, the email will pass DMARC, while replies will go to the original sender as though they’d originally sent the email to the new recipient. It’s a rarely used feature, but it’s there, living on as an artifact.

Forwarding only some of the things

Server-side forwarding, by way of ~/.forward files or your email account’s settings, sends along the full email, with the original sender in the From: field as though it never passed through another server. You’d often be none the wiser, if you didn’t check the email source for a resent field, as the full original email comes through, HTML and CSS intact, with the correct headers to pass authentication.

Eudora-style redirecting, similarly, sent along the full message as faithful to the original as possible. Aside from a by way of tagline in the From: field, you might easily overlook that the email came to you in a roundabout fashion. You’re also incredibly unlikely to receive a redirected email today, over a decade after Eudora was retired, and if you did it’d be more likely to be blocked by your server or marked as spam.

Both these automated forwarding options and many modern email rerouting setups run the risk of breaking DMARC, as forwarded emails are sent from the forwarder’s server with the From: field and most original headers intact. The sending IP address from the server forwarding the message won’t align with domain in the From: address, causing SPF checks to fail, and the original DKIM signature may fail if the secondary server modifies the email content in any way. That cascade of failures leads to a DMARC fail, resulting in an undelivered message or one marked as spam.

Traditional forwarding, copying-and-quoting the body, still works as it did in the MSG era. For all intents and purposes, when you forward an email, it’s a new email where your email app auto-copies and quotes the details for you. It's the safest way to share an email while ensuring there’s no server-side confusion over who sent the message.

But even straghtforward forwarding often break some things, even if it's most likely to pass DMARC. Formatting’s often a bit broken in forwarded HTML emails. Images and attachments might go missing, as may truncated text in especially long messages. That’s because your email app reformats the message based on what its editor supports, occasionally stripping out CSS and dropping oversized files. That, and the oddities of quoting a whole message can make things render differently than they usually would (which is why Outlook includes an option to Forward as attachment, including a complete HTML copy of the email for posterity).

Despite its issues, simplicity helped forwarding took off. Too well, at first, with early viral chain emails and hoaxes spreading across the globe. We learned to ignore emails that started with Fwd: Fwd: Fwd:, learned to shame overuse of the similarly too-easy reply all, and combined the best parts of both into early internet communities with LISTSERV and mailing lists.

Today, for most of us, forwarding isn’t the worst problem in our inboxes. It’s one of the best ways to share email newsletters, enough that some include a subscription CTA in the footer just in case you received the email via forward. Like many of the best things in life, it’s best in moderation—and with a moment’s contemplation if this email is truly worth passing along.

Image Credits: Header photo via Wikimedia. Eudora screenshot from Eudora documentation, courtesy of the University of Padova.