Sending a newsletter is easy.

...For you, that is. Open Buttondown, type out your newsletter, and click Send. Moments later, magically, your ideas appear in subscribers’ inboxes, each message a unique email customized for that recipient.

Behind the scenes, a Rube Goldberg machine makes that magic happen. Buttondown’s software grabs your subscribers’ email addresses from Amazon Relational Database Service, merges them with your newsletter text, and churns out one new message per subscriber. It then sends each message to the email delivery service Postmark, which in turn looks up each recipient’s email server and delivers their message. The email server accepts the message and, among other things, sends a notification to Apple or Google’s push notification servers, which relays it on to the subscriber.

Someone on a flight or in Frankfurt or Fort Worth clicks send, and a thousand phones buzz moments later. The modern-day equivalent of the newspaper’s hulking printing presses and network of newsstands and delivery folks.

Push notifications in your pocket aside, it all works more or less the way it has since email newsletters were first sent around 1980.

Why not email everyone?

The first newsletters, the paper fliers like Martin Luther’s Ninety-five Theses, were covertly nailed to doors and passed from one person to another. They relied on close-knit local communities to spread the word. Much like a flier advertising a bake sale at your neighborhood community center. With time, newspapers were eventually able to scale up to daily delivery, so everyone who wanted the news could get a personal copy on time.

Email took a similar path. The proto-internet, ARPANET, was a small, close-knit community of researchers and students and military generals, where emails passed between close-knit newsgroups. The goal was a network robust enough that the US Government could communicate after a nuclear attack. The result? Spam.

Only “about 2,600 users” were on that early network, in 1978, and each of their email addresses were public, in a paper phone book-esque directory. The perfect way to promote DEC’s latest computer, thought Gary Thuerk, who decided to mine that directory for leads and email them about a computer demo.

“There was no app for the email campaign. We just used our email program with its text editor,” Thuerk recalled. “I went through the paper directory and highlighted (in yellow) the names with email addresses that I wanted ... to put into our e-mail system.” Thuerk and team then dutifully entered each of the 397 email addresses into their email software’s TO field (which could only hold 320 addresses; the rest overflowed into the email body).

Header of the first spam email, with every recipient crammed in the To: field

“DIGITAL WILL BE GIVING A PRODUCT PRESENTATION OF THE NEWEST MEMBERS OF THE DECSYSTEM-20 FAMILY,” read that first bulk email.

Pandemonium ensued. “THIS WAS A FLAGRANT VIOLATION OF THE USE OF ARPANET AS THE NETWORK IS TO BE USED FOR OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT BUSINESS ONLY,” pounded out Major Raymond Czahor in reply. “We got a phone call from the Air Force Major who called to complain about what we did,” recalled Thuerk. And rightly so. The only vote in favor of what came to be called spam came from Richard Stallman (of GNU and open source fame). “I get tons of uninteresting mail. At least a demo MIGHT have been interesting,” said Stallman, before suggesting someone should start a dating service over email.

But there, in a lapse of judgment, was an idea. What if you could email everyone who wanted to hear from you, all at once? No more nailing theses to doors or emailing everyone, and incurring the wrath of priests and generals.

The first email newsletter

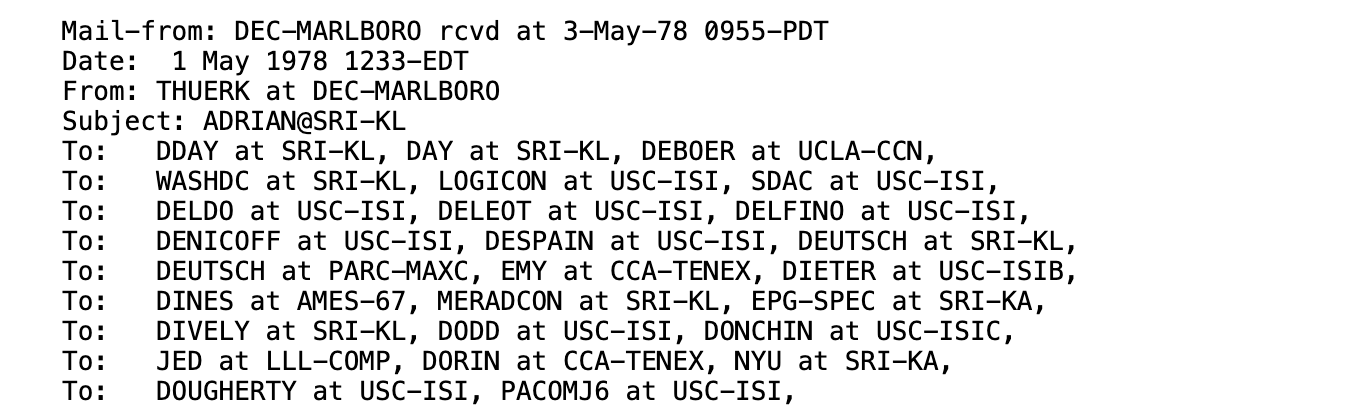

The first ARPANET Newsletter

ARPANET’s team took the first step (at least, that we could find), with their “ARPANET Newsletter.” This, too, appears to have been sent to everyone on an existing list: Those in charge of ARPANET nodes. Only, when the folks running the software send the email, it’s less spam, more in-flight announcement.

“DCA believes that it is a good idea to keep the liaisons better informed of actions that will affect you and your users over the next few years,” opened the newsletter’s inaugural issue on July 1, 1980. “To achieve this goal, DCA will publish a network newsletter which will provide management and technical information and guidance to you.”

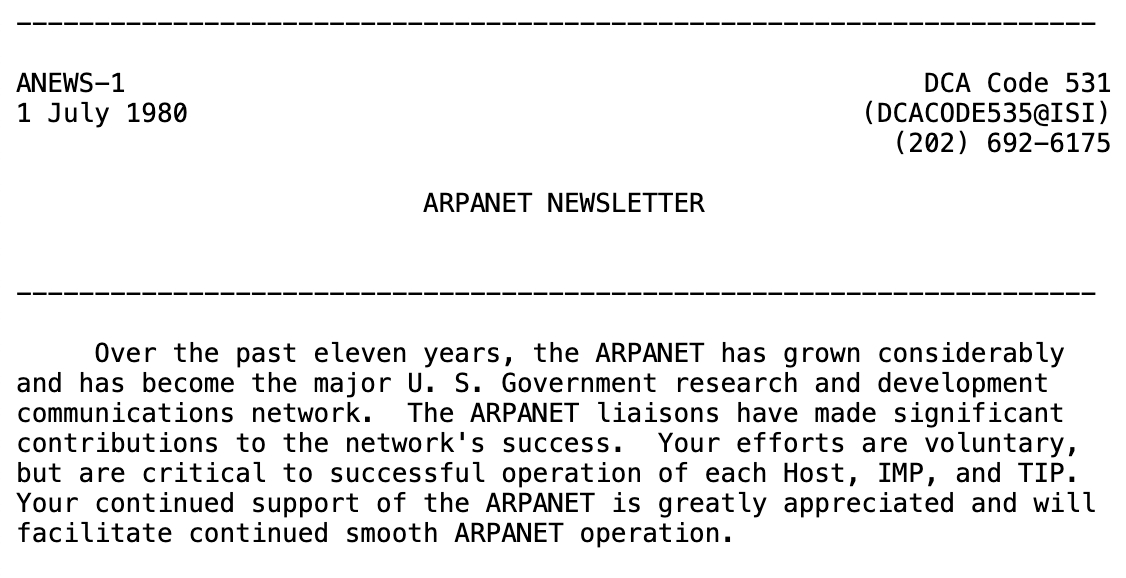

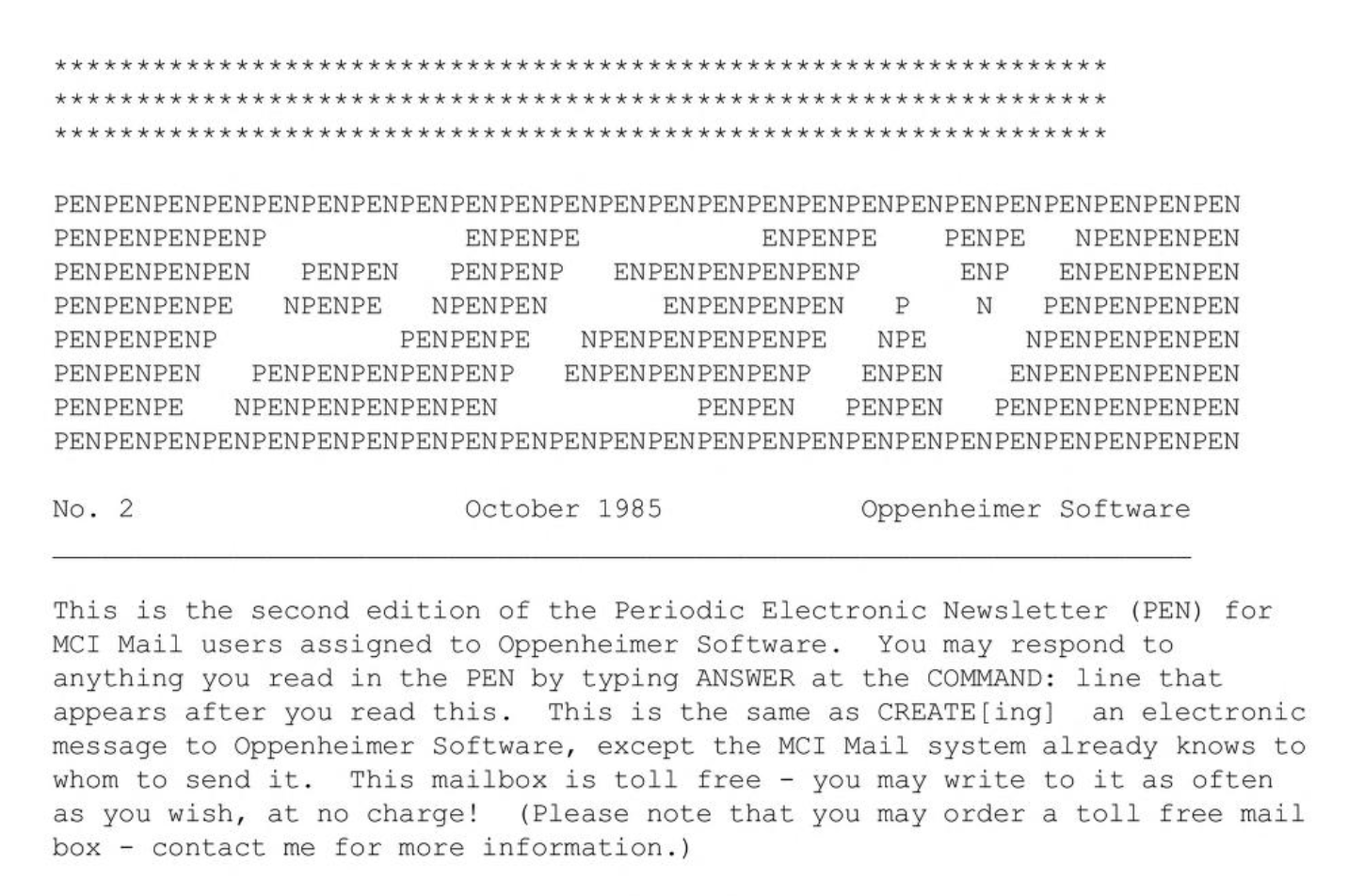

The second issue of the MCI Mail PEN Newsletter

Five years later came the first email newsletter on a commercial network from, believe it or not, another Gary.

Gary Oppenheimer, this time, a reseller of MCI’s early commercial email system launched in late 1983. MCI called itself “The Nation’s New Post System,” offered an email-to-print-letter service competing with the USPS’ own E-COM system, and let consumers send their first emails for $0.50 per 500 characters. And they relied on resellers like Oppenheimer to push email to the masses.

What better way to promote email than with email, thought Oppenheimer, who proceeded to start his MCI Mail PEN (for “Periodic Electronic Newsletter”) in October 1985. He, too, sent his newsletter to all of his customers, like modern software’s onboarding emails. It was email about email, sharing tips about MCI Mail and software to get more out of the service. It was popular enough that Oppenheimer "eventually became the firm’s largest global sales agent.” And, come 1989 with the advent of TCP/IP, it shared some of the first modern email addresses, including Oppenheimer’s own, GOPPENHEIMER@MCIMAIL.COM.

Everyone in one message vs. One message per person

It’s unclear how the ARPANET Newsletter and MCI Mail PEN were sent. Perhaps they used a custom script to send one mail merged email at a time. Or, perhaps, every recipient was crammed in the To field, DEC spam-style.

But bit by bit, the pieces were being added to turn email into a mass publication system. First up, a new email header: The BCC field.

A century earlier, carbon paper had revolutionized letter writing. Instead of penning a missive to a single person, you could stack paper interspersed with carbon paper and pen as many identical copies as your pen pressure could support.

Only, private letters carried an aura of privacy. You'd assume you were the only recipient, and might feel blindsided if someone else received an identical letter.

So the CC was invented. You'd note, on a letter, “cc.Mr. Smith” when a Mr. Smith also received the letter. It was a trust-based system, though, and sometimes you’d rather leave the illusion of privacy while still duplicating a document (and leaving a note to yourself of who all received the correspondence). Thus the BCC, or blind carbon copy. By 1957, Merriam-Webster found, the practice of listing the people who received a copy of a letter as a CC was standard, as was also listing privately copied people as BCC on the copy you kept for your records.

That carried over, as the world digitized. In 1982, BCC made its way to what were then called “ARPA Internet Text Messages,” that proto-email where spam and the newsletter were invented. Every recipient would see the primary recipient in the To field, but wouldn’t know who else might have surreptitiously received the email via BCC.

That works, to a degree, for small newsletters. Even today, if you keep your list under Dunbar’s Number, you could add everyone’s email addresses to BCC and send a newsletter straight from Gmail or Outlook without any additional software.

That, or automation, the better way to send emails to everyone. For one, you can customize the emails, merging in names along with email addresses. For another, your newsletters are more likely to be delivered, less likely to be marked as spam (and ready to scale to hundreds or thousands of subscribers).

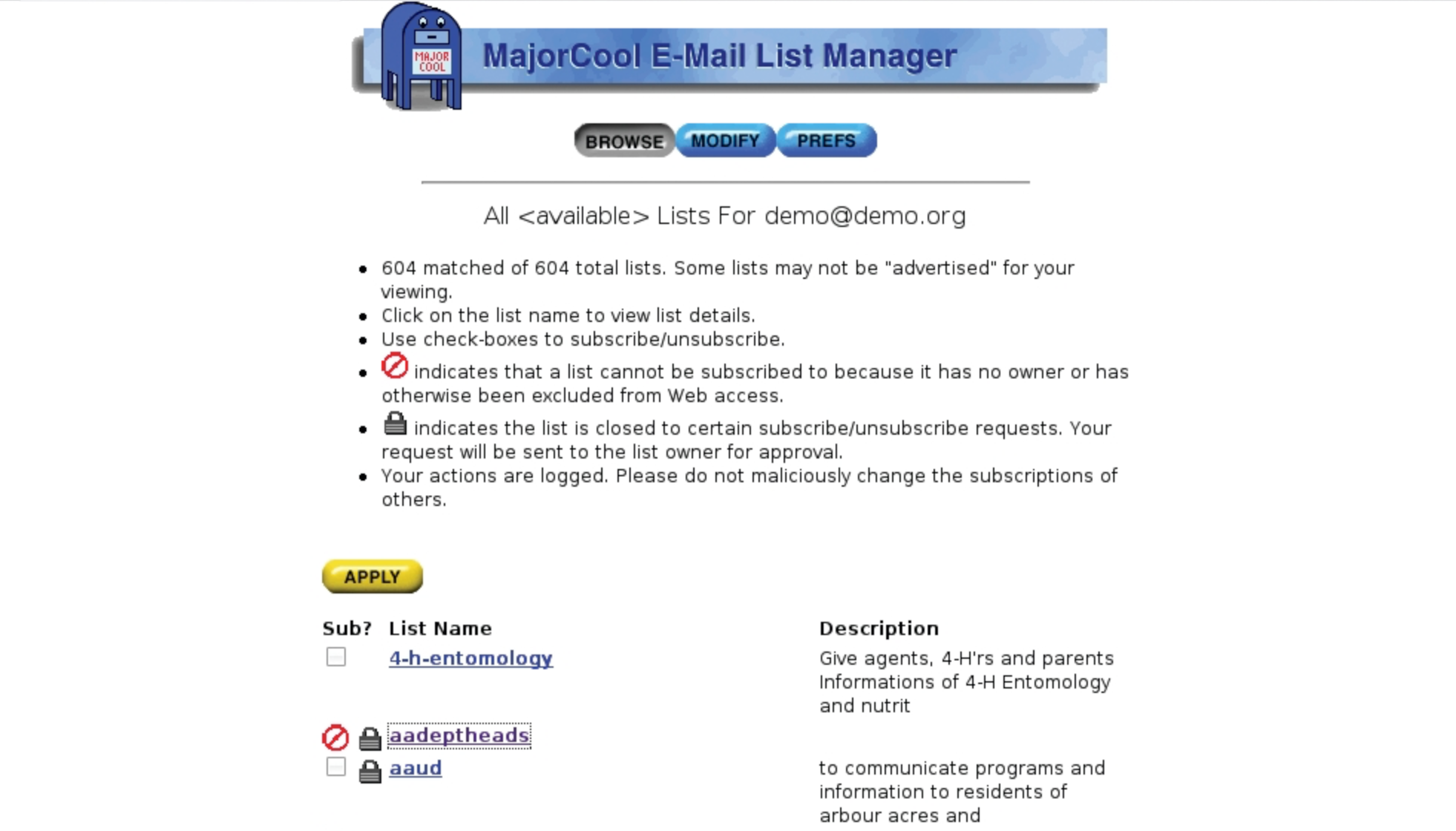

MajorCool’s front-end for Majordomo, via Linux Magazine

Listserv came first, as an automated way to send emails to a crowd launched in 1984 on IBM mainframes. It was designed for email newsgroups, where every email sent to the list was shared with every subscriber—original emails and replies alike—in a role taken on by Google Groups today. Handy to build a community, risky when gathering a large group of readers and putting publishing power in all of their hands.

Dedicated newsletter software came from a variety of early scripts. The W3 group, in late 1992, used a W3 mailing Robot to “accept incoming mail and allow remote users to subscribe to mailing lists (and unsubscribe).” Earlier that year, Majordomo had launched as perhaps the first software built specifically for email newsletters (or, at least, “moderated newsgroups” which, if you moderated out every reply, would be the same as a newsletter). It was a Perl script that would merge addresses with your newsletter copy, and send individual emails out via the UNIX sendmail command. And it, in turn, powered MajorCool in 1996, a “CGI application that provides Majordomo mailing list configuration and subscriber management via WWW,” for an early web app where you could add subscribers and write newsletters from your browser.

An early Campaign Monitor screenshot

Soon enough, email newsletters were by default sent from the browser. Digital Impact, launched in 1997, may have been the first—and by 2002 they sent email newsletters for everyone from Apple and Citibank to UPS and Xerox. “IMPACT is the first online direct marketing application built specifically for enterprise marketing teams to collaborate across departments, geographies,” said their SEC filing. Roving Software launched Constant Contact in 1998, as a tool for their clients to send emails, and called it “the first email marketing tool for small businesses, nonprofits, and associations.” MailChimp came in 2001, and by then, the pattern was well established.

You’d use an online form to add subscribers and write email newsletters. That app would trigger a server-side script to create the emails, then trigger another script to send the emails. Over time, the ingredients changed. Transactional email services took the place of sendmail, handling delivery and making messages less likely to get marked as spam. Managed database and file storage services simplified handling contacts and attachments. Where once a newsletter might have been sent by a handful of UNIX scripts, today’s newsletter apps rely on a handful of services that are each best at one task.

And that, from carbon paper to artisanal web apps, is why you can send your newsletter to everyone, today, without copying and pasting anything. That’s the value of a simple system like email: It’s infinitely flexible.