Email, for just under three years, came in a blue-and-white envelope from the United States Postal Service.

Every new technology, it seemed—telegrams, telephones, faxes, and faster delivery services alike—had threatened the Postal Service’s monopoly on delivering the mail.

This time, the threat seemed existential. A 1982 Congressional report predicted that “Two-thirds or more of the mailstream could be handled electronically,” and “the volume of mail is likely to peak in the next 10 years.”

Good thing the mailmen were ready. The Post Office had landed on a plan to co-opt the email revolution.

How do you get email to the folks without computers? What if the Post Office printed out email, stamped it, dropped it in folks’ mailboxes along with the rest of their mail, and saved the USPS once and for all?

And so in 1982 E-COM was born—and, inadvertently, helped coin the term “e-mail.”

Mail on the wire

The original study that recommended the USPS start sending email, for everyone.

It all started in 1971, when the Post Office Department was rebranded for the first time in its 179-year history and turned into the United States Postal Service. Through snow, rain, sleet, and gloom, they got nearly 87 billion pieces of mail through that year.

It’d weathered the elements, and now it needed to weather sweeping technological changes. So among the newly christened USPS’s first acts was to open an Advanced Service department and hire ex-Peace Corps analyst Gene Johnson to run it and decide how mail of the future should look.

The Postal Service had long adapted by embracing the new. Jeeps in lieu of horses, Zone Improvement Plan (or ZIP, as we’d come to know them) codes to automate mail sorting. The USPS couldn’t beat telegrams for speed, so they embraced them with a Western Union partnership to send “Mailgrams” next-day through the mail for $2.75 (a moderate success, that—incredibly—ran until Western Union terminated telegram service in 2006).

The next frontier to conquer: Electronic mail.

“There was billions of billions of billions of pieces [of mail] that were computer-generated,” said Johnson to Devin Leonard in his book “Neither Snow nor Rain: A History of the United States Postal Service.” That gave Johnson an idea. Each of those letters that were currently being created on computers, printed, and mailed, could instead “be sent directly from the computer into the Postal Service and sent out to the post offices for printing and delivering,” he surmised.

This could be big. Fifty million letters a year big, according to the Postal Service’s projections.

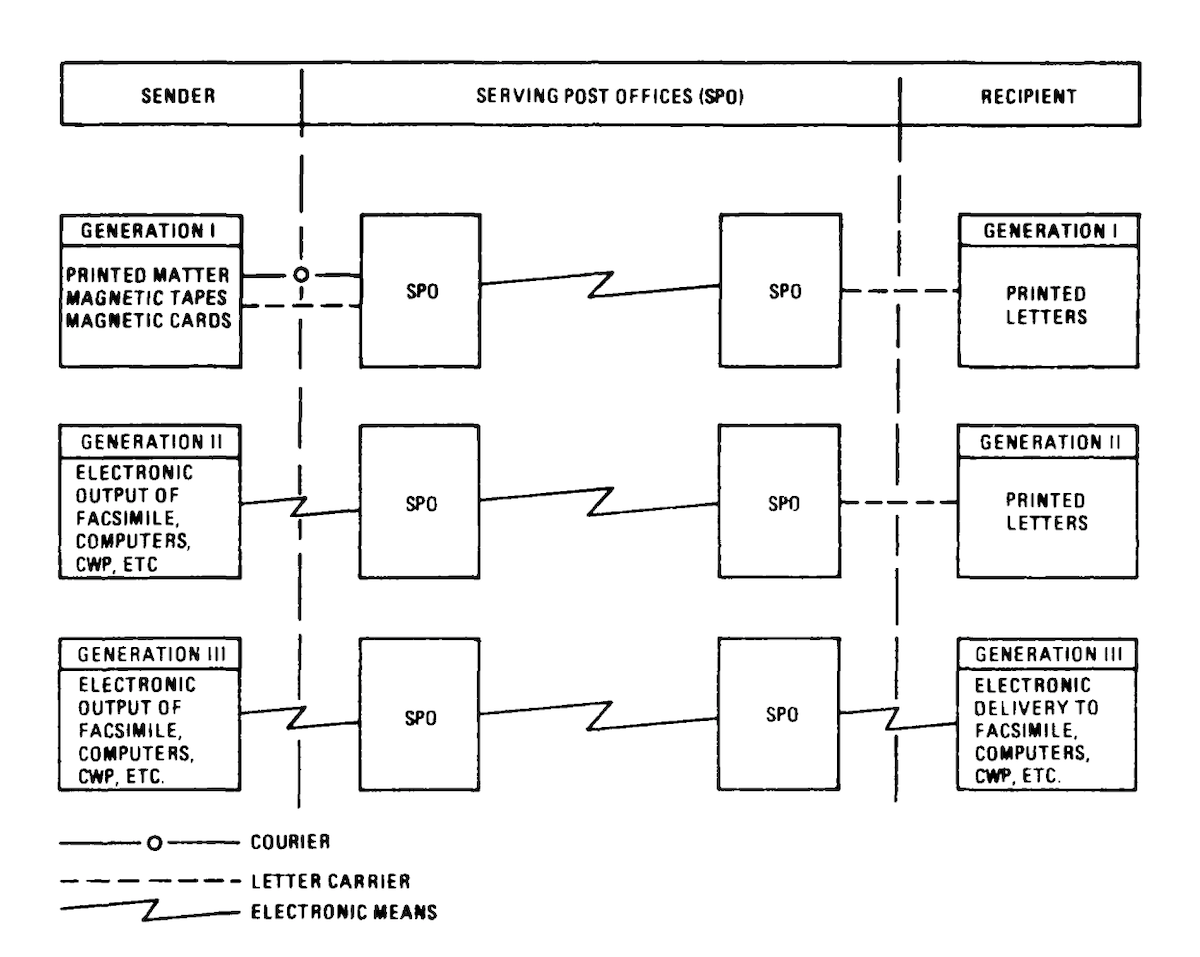

A diagram of the USPS’ ideas for how to deliver email—in print, and eventually online

So they went to the drawing board, and designed email on paper. The pitch was simple: “We convert your message, up to 2 pages, into hard copy. We fold it and insert it into an envelope. We seal the envelope and put it into the mailstream. Then, we deliver your message anywhere in the continental U.S.”

E-COM messages could be one or two pages long, with up to 41 lines of text on the first page and 56 lines on the second. You’d type up the messages, then send them via TTY or IBM 2780/3789 terminals to one of 25 post offices. There, a Sperry Rand Univac 1108 computer system would receive your messages.

E-COMs could be “Single Address Messages” with a letter for a single recipient, “Common Text Messages” with a single bulk letter intended for multiple recipients, or “Text Insertion Messages” with form letters blended with text to be inserted into the message for an early take on mail merge. The Univac would print your emails, then postal staff would fold them, stuff them in envelopes, and send them on their way.

The team had this one shot to keep the Post Office afloat. “In the future, the only way the Postal Service will be able to keep its volume rising and finances dependable is through participating in electronic mail services,” read the 1979 Annual Report of the Postmaster General.

And then bureaucracy bit.

Email by fiat

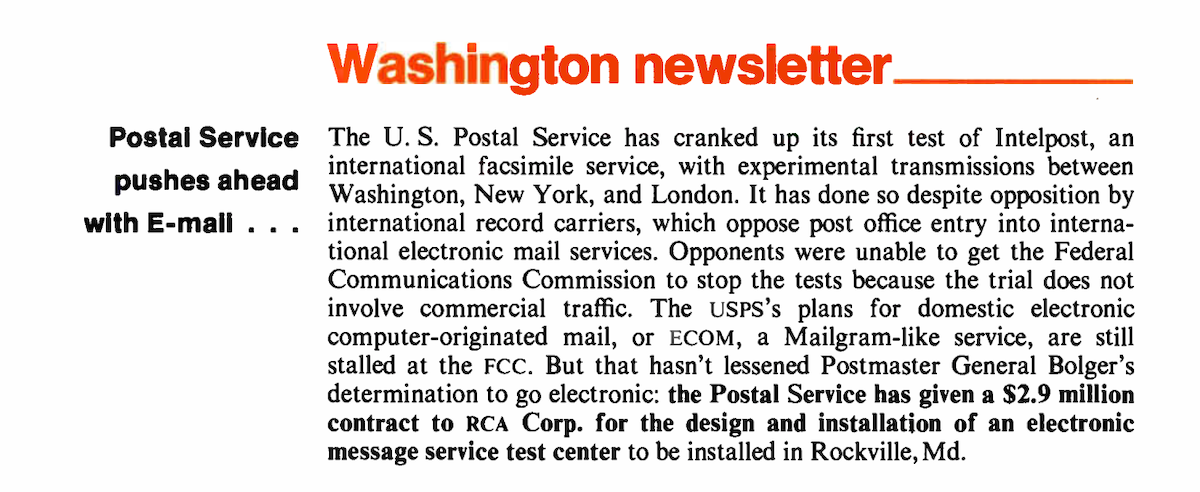

The first print use of the word “e-mail” as the FCC worked to stop the Postal Service from sending electronic messages

Optimism prevailed at first. Postmaster General William Bolger suggested charging the price of a stamp—15¢, at the time—per E-COM message, and even thought they could lower the price over time. The team promised two-day delivery, but that too they hoped to reduce to one day with volume.

And, perhaps, that volume would be easier to hit, imagined the Post Office, if Congress would authorize an expanded monopoly. The Postal Service proposed it should have “monopoly over delivery of hard copy associated with electronic messages,” said Postal Rate Commission chairman Janet Steiger in December 1978, carefully defined so Western Union, say, could still deliver telegrams while the Postal Service could have a monopoly over delivering printed email messages. “The Postal Service intends to stand on its right to be the sole delivery agent for such mail when delivery is in hard-copy form,” noted a Defense Communications report. And it was trialing sending electronic messages itself, without print—expanding its mandate.

“Postal Service pushes ahead with E-mail,” opined the Electronics journal headline in June of 1979, as the case worked its way through the courts, inadvertently using the phrase “e-mail” for what the Oxford English Dictionary believes is the first time.

It was not to be, thanks to the FCC. “The FCC interpreted the law as giving it jurisdiction over all forms of electronic communication, including incidental physical delivery.” Thus was averted a postal monopoly on printed emails.

But legal ambiguity continued to cloud the project. The Postal Rate Commission took 15 months to review E-COM—long enough that standard postage went up 5¢ in the interim. It barred the USPS from operating its own electronic networks, just in case the Post Office decided to deliver messages electronically and in print. And it raised the price on the service to 26¢ for the first page, plus 5¢ for a second page.

Sending the messages wouldn’t be simple, either. Customers had to register their company with the USPS using Form 5320, pay a $50 annual fee, send a minimum of 200 messages per post office, and “prepay postage for transmitted messages received, processed, and printed for each transmission,” dictated the 1981 Federal Register.

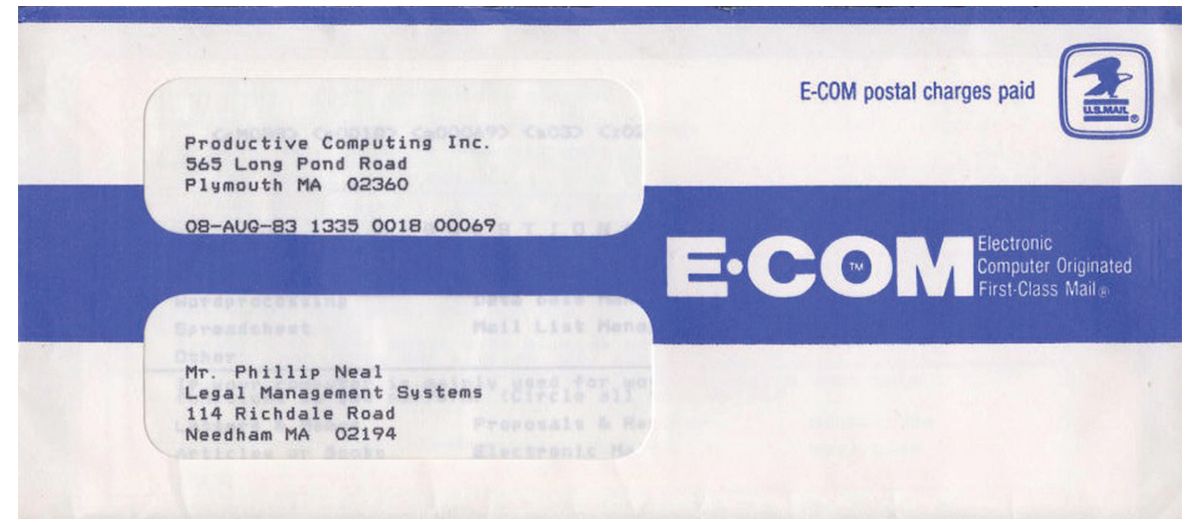

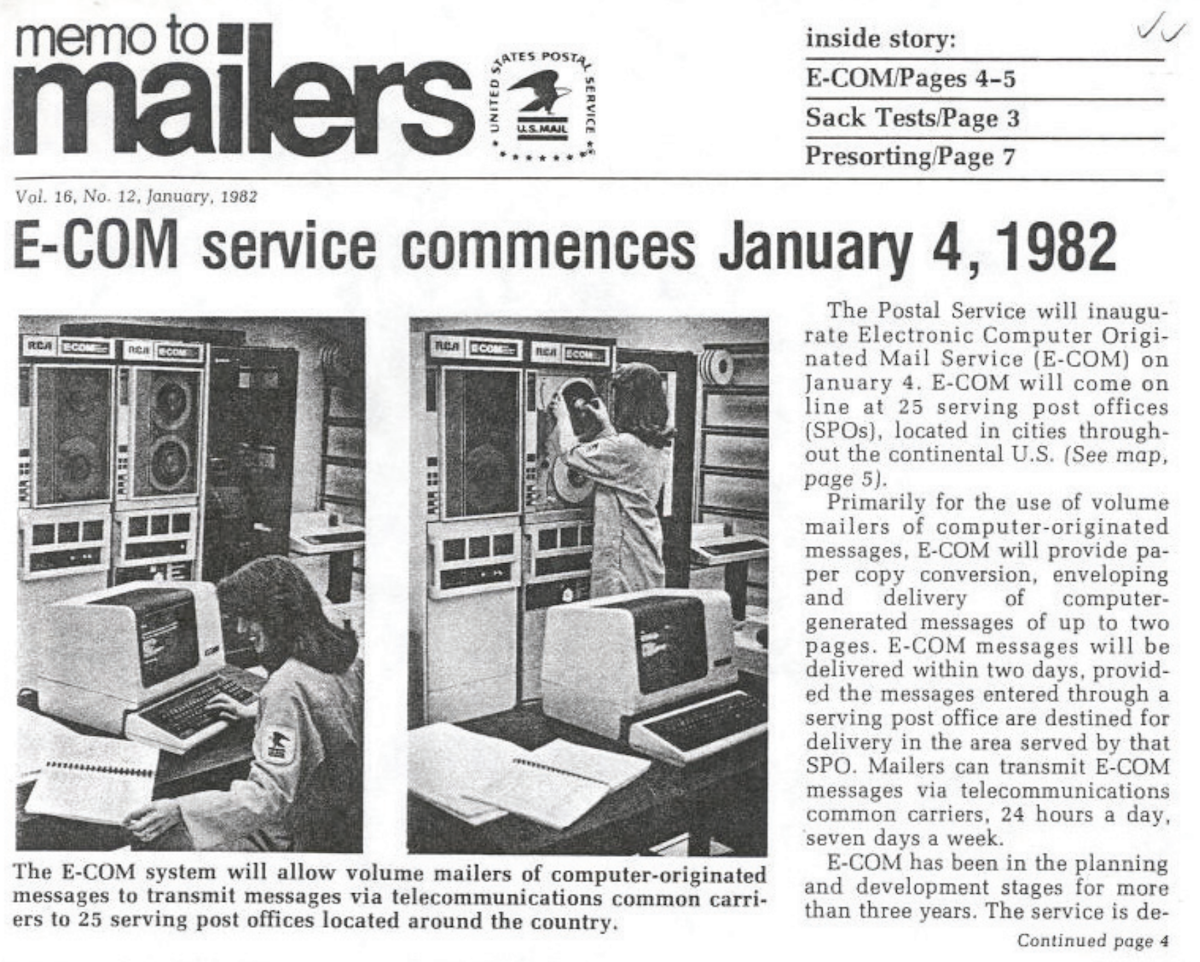

An E-COM-branded computer, handling E-COM mail for the USPS

Yet, at least the system was finally ready to launch. “We are very proud of this milestone in the history of the Postal Service and pleased to share this occasion with you through this message,” wrote Postmaster General William Bolger in the first E-COM on January 4, 1982.

Within that first year, the post office had delivered 3.2 million E-COM messages for 600 customers. Fifteen million messages the following year, 23 million the year after that. It wasn’t the breakout, 40-million-messages-a-year success they’d dreamed of, but the post office was delivering millions of real emails to people’s mailboxes, in print.

You’ve got mail

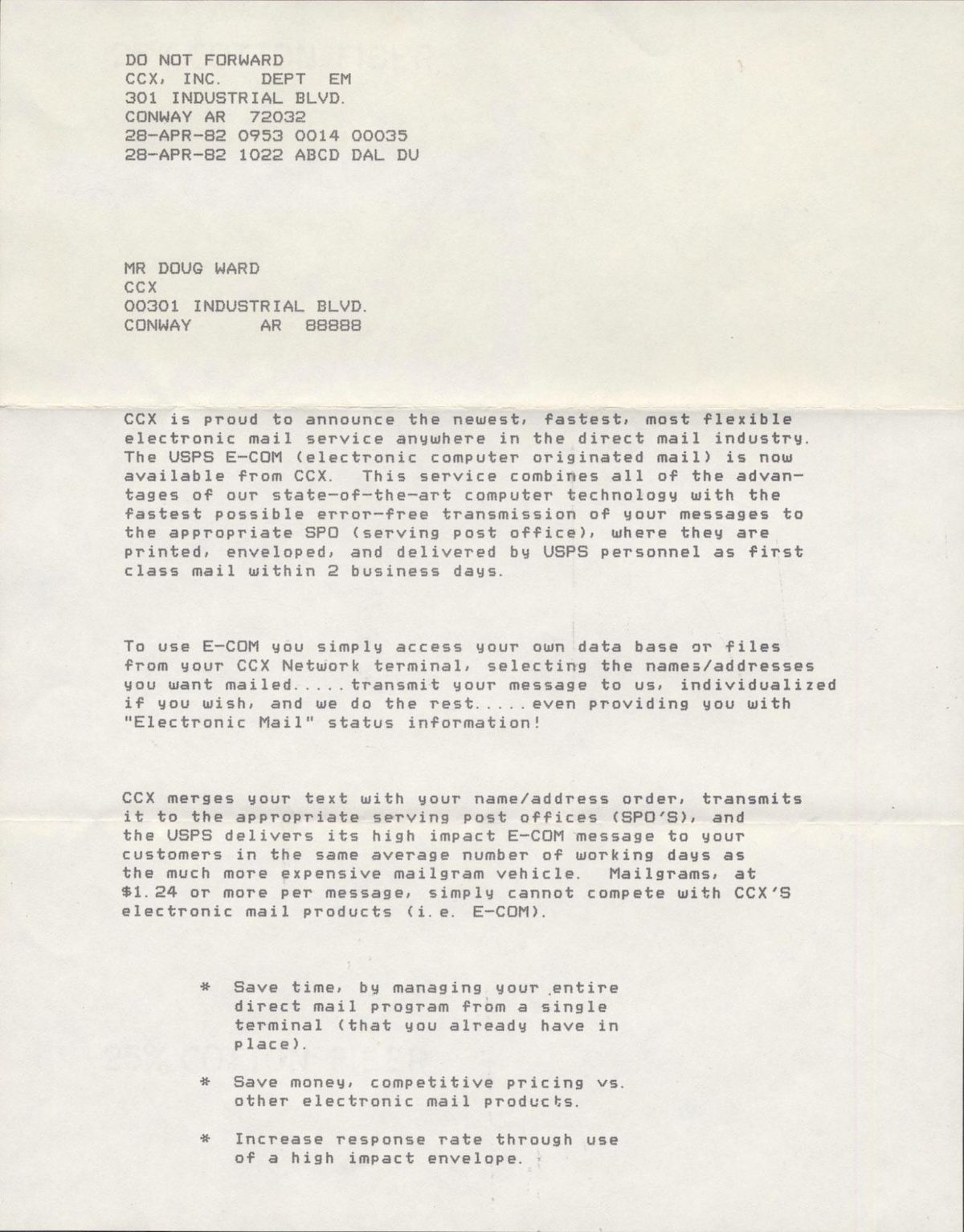

An E-COM letter, shared on Twitter/X by Doug Ward

“Imagine: if there was some way to increase the impact of your mailings—while decreasing the aggravation,” said the Post Office as it promoted its new electronic-message-to-print-mail service.

Some early adopters braved the challenges and took the Post Office up on its offer. With their official-looking, blue-and-white envelopes, “an E-COM letter carries a lot of weight with recipients,” advertised the USPS. Bank of America used E-COM partly to expedite overdue payment notifications, partly because the envelope “draws attention,” said a bank official.

Others turned to service providers to overcome the technical and bureaucratic challenges. “A company called CompuServe will let you send a single letter using their interface to E-COM for $1.26,” suggested someone in a Usenet thread. The New York Times, meanwhile, reported that “so far 70 percent of the messages have come from one company, Western Union Electronic Mail Inc,” two months after the E-COM service launched.

An E-COM advertisement from Forbes Magazine on December 19, 1983

And it worked. “The post office printed a hard copy and sent it by carrier. The messages usually arrived the next day,” recalled Seth Steinberg. “I used it to E-mail my parents and other family members.”

“‘Neither system downtime, line noise nor software bugs’ had stayed the new service from its appointed rounds,” enthused another customer to the USPS.

But it worked at an impossibly high cost. Every time a customer spent 26¢ to send those eye-catching blue-and-white envelopes that first year, the USPS lost an astounding $5.25 in printing and delivering them. Volume wasn’t enough to stop the bleeding; the second year, the USPS still lost $1.24 per E-COM it sent. And despite that implicit subsidy, and full-page ads across major magazines, the limitations—no custom font, no letterhead, no return envelopes, and no fewer than 200 recipients per post office—kept early adopters like Shell Oil from using E-COM.

The one group who loved E-COM? Junk Mailers.

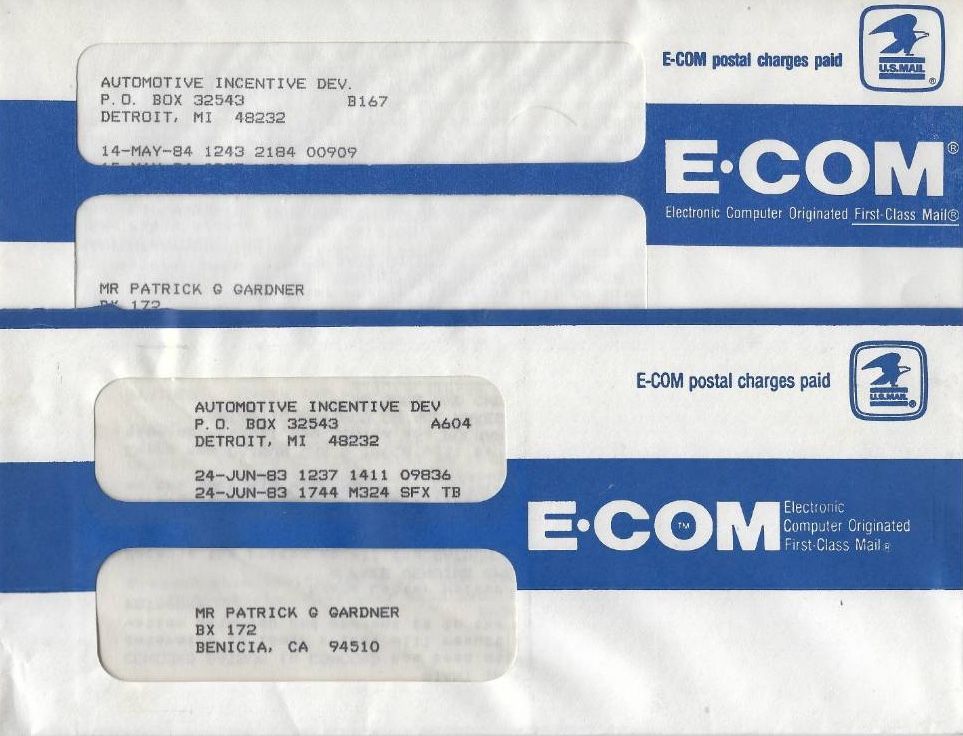

The vast majority of E-COM messages came from this one sender (via @patg23 on Stamp Community)

Of the 15 million E-COM messages the Postal Service delivered its second year in operation, “between one-half and three-fourths” were sent by Automotive Incentive Development Co., a direct-mail advertiser, according to a Washington Post investigation. As few as six companies accounted for “well over 70 percent” of E-COM messages sent, said E-COM director Karen Uemoto.

If E-COM wasn’t worth the trouble for companies like Shell, it clearly was worth it to a tiny handful of companies that valued the credibility that E-COM’s official, blue-and-white envelope lent. “The distinctive look of an E-COM letter carries a lot of weight with recipients,” advertised the USPS, and clearly direct mailers took the hint. Automotive Incentive’s letters were so common, of the less-than-a-dozen surviving E-COM envelopes we could find online, two of them were sent by Automotive Incentive.

When the best reason to use the service was its eye-catching envelope, the best way to use it was through a third-party service, and the post office was still losing money sending the messages, something was wrong.

Goodbye, E-COM. Hello, e-mail.

Another E-COM advertisement, from Time Magazine, May 1983

The USPS could change little on its own. Even a price increase had to get approved—and eventually cut—by the Postal Rate Commission. Finally, enough was enough. The USPS Board of Governors decided to “dispose of the E-COM system by sale or lease.” No buyers were forthcoming, so the post office shut E-COM down, sending the last message on September 2, 1985—with a cumulative loss north of $40 million.

And it was ok. Mail, it turned out, was more popular than ever. Throughout the .com bubble of the ’90’s, first-class mail volume continued to rise, peaking in 2001 at 103 billion pieces. The USPS regained its confidence; "E-mail is not a threat," USPS spokesperson Susan Brennan told Wired that year. The doomsayers, at least momentarily, were wrong (though eventually would be proven right, as mail volume has fallen every year since then, to 45 billion pieces in 2023—the lowest volume since 1968).

E-COM wasn’t the last time the Post Office decided to give email a try. “The Postal Service is, and always has been, one of the most high-tech companies in the world,” insisted Brennan to Wired. There was a plan, during the Clinton administration, for the postal service to give every American an @.us email address. And there was a plan for a Digital Postmark, a way to electronically sign emails through the USPS, that ran until 2010 then went quietly into the night. Johnson, even, managed to make the E-COM idea work in the private sector. He started Mail2000 in 1996 to print and mail letters for businesses—then sold it, five years later, to UPS for $100 million.

We the people were left with the name, e-mail, that over time lost its hyphen and became our universal inbox and digital passport. We were left with emails that’d remind us not to print them out, with one of the few decentralized networked systems that’d survive the internet and social networking. And the Post Office was left to deliver the e-commerce packages we’d ordered online, as email, chat, and push notifications ate away at all the reasons we’d have sent first-class mail in the past.