You know them as the junk at the end of links, the query strings that start where your domain ends, things like ?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social. Their raison d'être is self-evident. You see utm_source=chatgpt.com on the end of a URL and realize that ChatGPT wants sites to know it’s sending them traffic.

They’re varied, defining medium (email or social, say), source (Google or Facebook or ChatGPT or any random site), campaign (where things start to get cryptic, with self-evident items like black_friday and less evident ones like any string of characters), and more. Yet long or short, detailed or not, they always start with utm.

Coined in 2002, when Windows XP and IE6 were new and the first Blackberry phone had just launched, the UTM over two decades later remains the best way to see how people found your site and if your newsletter sent traffic to the pages you wanted it to.

And it started with an urchin.

On the origin of UTM

Urchin was “too blue blue blue blue blue,” said Earthlink VP Scott Crosby.

A UTM is a query string, a bit of code tacked on to the end of URLs to detail a visitor’s origins. They, by themselves, are little more than extra text. But a server or analytics software can log that text, and remember not only that someone visited your site, but also that they visited with a specific handful of UTMs attached to their link. That data is at the core of most analytics on the web today, the thing that tells marketers if their campaigns got awareness or their ads paid off.

Universal tracking mechanism, perhaps? Unusually transparent monitoring? That or something similar would make sense as the source for the UTM acronym, something that evokes its purpose. But no: UTM stands for Urchin Tracking Module, a fossil of 2002 that lingers in analytics over two decades later.

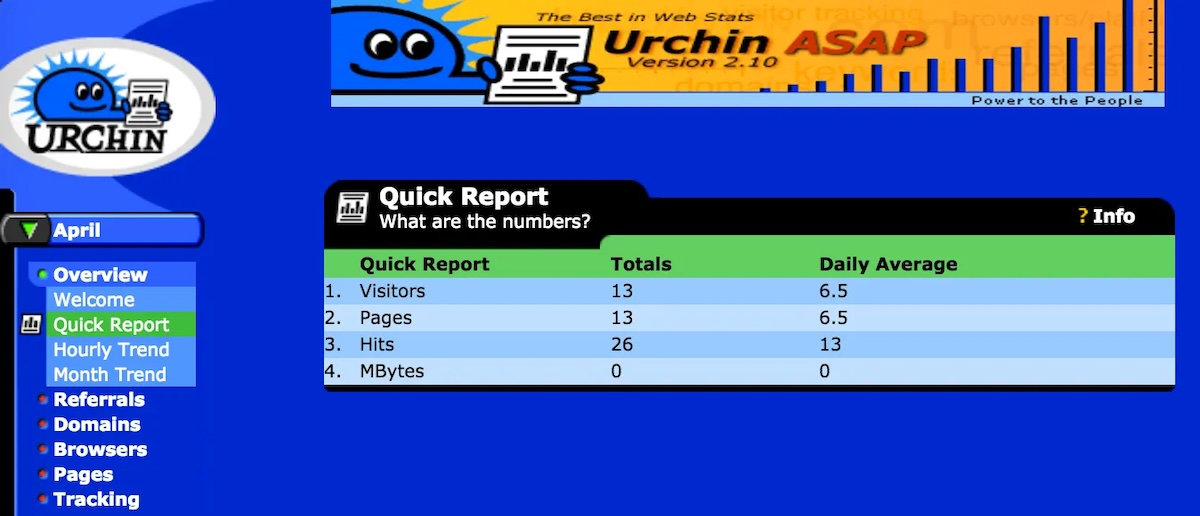

It started, just as the dotcom bubble was beginning to inflate, with a web design agency in 1995 building websites for the likes of Pioneer Electronics’ LaserDisk and Caterpillar’s Solar Turbines divisions. Each site took up precious space on their Sun SPARCstation server and bandwidth on their ISDN line, and they needed to bill each client appropriately. So the team threw together a few scripts to analyze server logs, wrapped it in a web dashboard, and voilá: The tool that was years later to become Google Analytics.

What to call this fledgling new product, an add-on to the core business of building websites? “We had this one customer… that would call us all the time and just talk forever,” recalled co-founder Scott Crosby later on a podcast. “We ended up calling him ‘The Sea Urchin’ because he would stick to you. And he would never let go.”

Gradually, Urchin turned into a shibboleth, “a generic term for anybody that would just latch onto us and waste our time.”

“And so, one day,” continued Crosby, “we’re thinking about what are we gonna call [our company] ... And so it doesn’t make any sense, but we just said, let’s call it Urchin.”

Urchin 4’s dashboard, inspired by Apple’s Aqua and powered by UTM data (via Tracking Garden)

One feature and customer at a time, Urchin Analytics became a major player in the fledgling web analytics space. Honda America used it. As did every Earthlink site. By 2002, Urchin 4 launched with the feature that lent it immortality: The Urchin Traffic Monitor, as Crosby says it was called at the time, shortened to UTM (the backronym that stuck to this day in Google Analytics’ documentation, though, was Urchin Tracking Module, either a co-name for the feature or one added later). Three years later, when Urchin was acquired by Google and rebranded as Google Analytics, UTM stayed on as what’d increasingly be the internet’s standard way to track how and why someone came to one’s website.

UTM was “specifically designed to provide the most accurate measurements of unique website visitors,” describes Google Analytics’ Urchin documentation. It contained multitudes: A UTM Sensor script on sites to track visitors with cookies to mark them as unique, and a UTM Engine server to log all the visits and turn them into dashboards. But its most memorable component was UTM parameters, the utm_source=google bits on the end of URLs.

Other analytics software could, at best, build their own take on similar features to what Urchin and Google Analytics offered (harder originally, easier today after the UTM patent expired in 2023). But any software could log UTM codes when someone visited their site with them appended to the end, and could parse them out to build a clear picture of how visitors ended up on their site. Even without a cookie to tell if the person had visited a site before or without HTTP referer headers (neither of which a link clicked from an email newsletter, say, would include), a UTM gave enough data to link the visitor to the ad or promotion that sent them your way. Even a human looking through logs without any specialized software could make sense of the UTM alphabet soup.

And so quickly enough, partly from the power of Google’s insistence, partly from their plain text simplicity, UTM parameters became the standard way to track the way people navigated the web via links, from early support in apps like MailChimp in 2009 to seemingly every ad and analytics tool today. Even as Google replaced other parts of Urchin over time, UTMs remain the standard way to tack data on to the end of URLs, everywhere. They’re useful on the web, where everyone wants to know which half of their ad and marketing budget they’re wasting, and even more on the web’s auxiliaries like email and real-life QR codes, where there are few other ways to ascribe source to a visit.

Putting UTMs to work

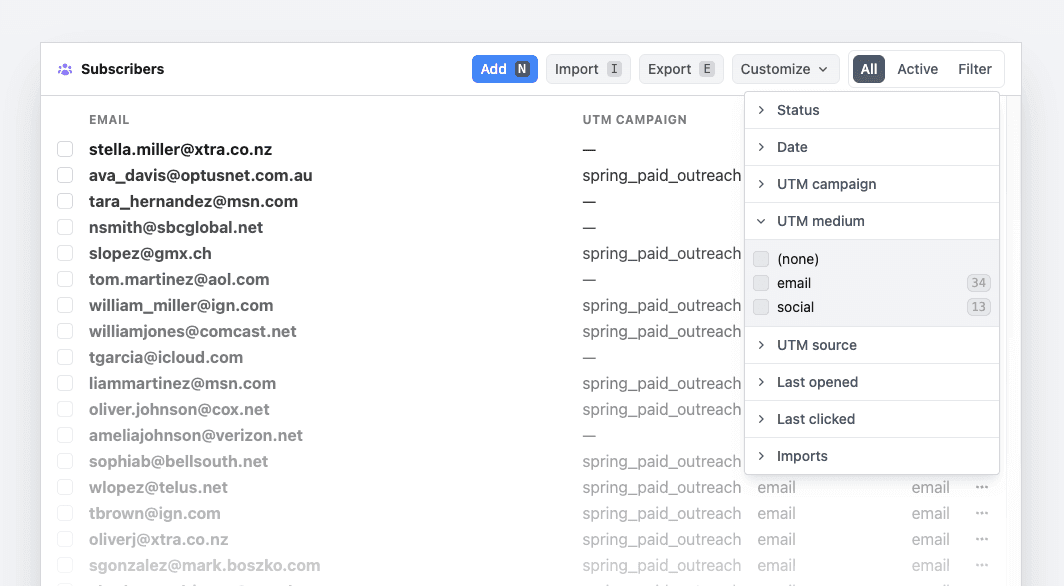

UTM filtering for your email data, in Buttondown.

UTMs require little more than a valid parameter, a value, and ampersands to separate them. Take any URL (https://yoursite.com/about, for example), add a question mark to the end like so (https://yoursite.com/about?), then add the UTM parameter such as utm_source with a value separated by an equals sign (for a full URL like https://yoursite.com/about?utm_source=newsletter). Want to add another UTM parameter? Tack an ampersand on the end, and continue (https://yoursite.com/about?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email).

That’s it.

Technically, you could track the same stuff with any value. You could have your server log any bits of text that come attached to URLs, and log source=google directly without the utm_ prefix. Yet standardization counts for something, and when seemingly everything supports UTM, those four extra characters are worth their weight in gold.

Google lists nine standard UTM parameters, but the most common are the ones that Google Analytics requires and most platforms support out-of-the-box:

utm_source: Who sent the visitors, typically a site likegoogleorfacebook, a type of content likenewsletterorapp, or a non-digital source likeflyerfor a URL in a QR code on a print sign, if you wanted.utm_medium: How visitors found the link, typically via a type of site likesocial, a type of content on the site likecpcfor paid ads, or a non-site source likeemailfor a newsletter.utm_campaign: Why the link was there, to attribute clicks to an ad campaign, promotion, launch, or any other reason to be.

A couple others are common enough to keep in mind, too:

utm_term: What one searched prior to clicking the link with a+or%20in place of spaces, likebest+email+newsletter+platformorbuttondown%20app.utm_content: Which content contained the link, to differentiate, say, links in your newsletter’s copy from your logo or other linked images in the email.

You’ll notice a common denominator: Each UTM parameter can be anything you want it to be. You could make the source be 1 or the medium be stagecoach if you so wanted. As long as you can make sense of the end data, anything goes. Just like email, like the web itself, like so many standards that have passed the test of time, UTMs are straightforward, simple, and malleable enough to do anything one wants them to do. And despite Google’s insistence of including the default three, you can get by with a single UTM (stick to utm_source if you want to keep things simple; it’s the default, and most likely to get logged everywhere), and the value you include could be anything.

Which opens the gates to doing anything you want with UTMs—part of the reason for its universality and longevity. You can use them to track which of your visitors come from email or social, and if the social ones came from the network for bragging about business or the one for bragging about babies or the one formerly known for a bird. You can track which specific email sent people to your site, or which specific link in your email got clicked the most. You could segment your email subscribers who clicked a specific link in a specific email on the day you sent it—and, therefore, proved they’re the most interested in your book launch or pop-up newsletter or meetup—and send them a special mailing.

You could do all that, and more, with UTMs, with just a bit of plain text clinging on to the end of your URLs, even if you never use Google Analytics.

UTM forever

“I didn't see Google Analytics coming,” Adobe Analytics née Omniture founder Josh James recalled in 2010, when the analytics market was fragmented among 80 competitors. Yet when Google acquired Urchin for around $30m in March 2005, quickly rebranded it as Google Analytics and re-launched it for free, and through it all kept the UTM prefix, what could have, otherwise, been a feature and term lost to the onward march of technology became immortalized.

Google Analytics turned web analytics from an expensive nice-to-have into a default thing most new websites incorporated to track their visitors. “We were acquired by Google because it saw the potential of data to create a better web,” Paul Muret wrote in Google’s acquisition announcement. “By liberating this tool we could empower companies of all sizes to become smarter and more effective online.” Omniture’s team was more jaded—or clear-eyed, perhaps—about Google’s take on analytics. “They're giving it away for free because they're trying to get data from customers,” said James (don’t worry: It worked out for them, too, when Adobe Analytics acquired Omniture for $1.8b).

But a free product that originally retailed for $499/month was hard to resist. Google Analytics popularity set the standards; even Adobe Analytics ended up supporting UTM tags.

While the Google Analytics tracking script’s property ID eventually switched from a UA- prefix, equally for Urchin Analytics and Google’s later branding of Universal Analytics, to a G- prefix with Google Analytics 4’s launch in 2023, UTMs carry on strong today. “It was nice of Google to allow that to stay,” said Crosby of UTM’s longevity. “I figured they must have thought it was too much trouble to change it.”

Scrappy consultants turned product developers gave us the UTM; inertia and the long-tail power of free software turned it into a standard. If the Lindy Effect holds, we’ll still see, clinging onto the end of URLs, codes named for the sea urchin and, indeed, for an overly clingy customer, in 2046—a hundred years after the ENIAC was unveiled.