So, you’ve created a newsletter. Presumably you want people to read the newsletter. Now that your mom has subscribed, a dilemma arises: how to find more readers?

Actually, this dilemma persists even if your newsletter is successful, because writers always want to expand their reach. That’s the magic of writing — it’s not just communication, but scalable communication. You can write once and reach many people.

Whether your mailing list is brand new or several thousand emails deep, you probably want to grow your subscriber base. Offering a lead magnet is an effective method to lure in new readers.

Admittedly, the word “lure” implies one of those mermaids who drowns lonesome sailors. Don’t worry, it doesn’t have to be like that! Ideally, your lead magnet is more like the sidewalk sign outside your favorite brunch spot, advertising bottomless mimosas to passersby.

A lead magnet is something you offer for free in exchange for the recipient’s contact information. It’s such a powerful technique because:

- People love free stuff. As a general principle.

- The people who want your free thing in particular are especially interested in the topic, and thus make a great audience for your writing… plus any paid products or services you may offer.

Back in ye olden days, the bank would give you a free toaster if you signed up for an account. The gimmick was powerful enough to become “a banking cliche, but that’s probably because it works.”

Definition

A lead magnet is a valuable free resource that you offer to your website visitors in exchange for their email address. This could be:

- an ebook,

- a checklist,

- a template,

- any other content that your target audience would find helpful.

By providing a desirable asset up-front, you can entice more people to subscribe to your newsletter and continue receiving valuable information from you.

Basically every single ecommerce website does this. “Join our mailing list for 15% off your first purchase!” Of course, the hope is that the discount code will be a deal-sweetener that prompts you to buy something immediately. But even if you submit your email, then get distracted while browsing and don’t make a purchase, it’s still a win. Now the brand has a ticket to your inbox 😏 They can send reminders about your abandoned cart, alert you to new collections, announce future sales, etc.

The “lead” part of “lead magnet” refers to the sales jargon of leads — people who might buy your product if “nurtured,” AKA reminded of your existence a few times. (A lead moves down the funnel to becomes a prospect once a relationship is established.)

You’ve probably been on the other side of this equation, encountering various offers around the web. I bet you hemmed and hawed about whether you wanted the free pre-formatted spreadsheet — or whatever — enough to bother signing up for an account. Does this 15% discount outweigh the consequences to my inbox? That’s why Gmail invented the Promotions tab.

I gotta admit, personally I almost always decline. I’d rather avoid the bother of unsubscribing from the newsletter later. Some people have a separate throwaway email they use to sign up for offers, the inbox of which is ignored. (Honestly a good strategy, I should start doing that…)

There’s the rub. Your lead magnet has to be good enough to be worth it. Ideally it’s so good — so well-targeted — that people are excited to start receiving emails from you. In the best case, joining your mailing list feels like an extra perk rather than a cost.

How do you achieve that? Know your audience.

Customer Persona

Who is your ideal subscriber, and what do they want? Better yet, what problems do they have that you can solve? For example…

Let’s say you have a personal style newsletter. Your ideal subscriber is a late-30s woman named Samantha who works in an office. She’s pushing for a promotion this year, and she wants to make the jump from renter to homeowner before she turns 40. Samantha has a comfortable budget for clothes, but she’s not rolling in dough — she buys Coach purses, not Chanel. In other words, she’s budget-conscious enough to love a good sale, but the sale might be at Nordstrom.

Samantha feels vaguely unsettled by Gen Z becoming the “cool generation,” making fun of the millennial trends from her teens. Looking nice and feeling put-together is important to Samantha, but she’s anxious about the prospect of updating her wardrobe as her career advances. How should she balance the desire to be “with it,” not dowdy, with the desire to feel like herself? All without breaking the bank?

Samantha needs a guide to curating a professional capsule wardrobe that will transition easily from meetings to happy hour. She needs examples of adult but fashion-forward silhouettes. She needs help identifying which $50-150 blouses are worth it, due to the materials or construction quality, and which ones are a waste of her budget.

If an influencer she trusts offers one of those ideas as a free download, you know Samantha is swiping up for the link.

That’s enough about Samantha. We wish her well, but her particular concerns aren’t really the point. The point is that she has particular concerns — based on her identity, her lifestyle, and her hopes for the future. Your ideal subscriber does too, whoever they may be.

Imagine the person you’re trying to reach, in detail. What’s bothering them? How can you help them move toward their goals with confidence?

In fact, don’t just imagine your target audience. Find where they hang out online, and observe what they complain about.

This is a type of ethnography, and it’s how some of the biggest hit products were invented. Consider the origin story of the Swiffer, which consultants created for Proctor & Gamble:

Continuum researchers videotaped people cleaning their homes and realized just how much people hated touching dirty mops. They also realized that most dirt in the home is primarily dust that could be picked up electrostatically.

Paying attention to the people you want to serve is essential. In the case of the soon-to-be Swiffer, close observation led to clever innovation:

It became clear that floor cleaning was a complex process. The women had to assemble a system of products to get the job done, most of which we had not initially thought of as being relevant to our business. We noticed that generally people swept the kitchen floor before they mopped it, so dustpans and brooms were part of the system. Often people wore old clothes because cleaning a floor was a dirty job. This was the first contradiction we noticed: when you clean, you get dirty. Often people had to move furniture to get easier access to the floor. We saw that people used vacuum cleaners on carpets, but vacuums did not work well on hard floors.

But the real epiphany came after we got back to our studio and looked at the videos. We listed each of the steps required to clean a floor: move furniture, sweep loose dirt, locate components, mix solution, prepare mop, and so on. It was a very mundane list, but when we put on our anthropologist hats and tried to see what was going on outside of any preexisting framework, we noticed something strange: about half the steps were for cleaning the floor; the other half were for cleaning the mop. If we had come down from Mars we might have concluded that the women were not floor cleaning, but mop cleaning! Why was this?

The experts on detergent chemistry had talked about a successive mixing model: dirt is dissolved or suspended in the soapy water stored in the cells of the mop; when the mop is rinsed, this dirt is mixed with the cleaner water in the bucket. As a result, the water in the mop gets cleaner and the water in the bucket gets dirtier. This might be a useful model if you're in the detergent business, but we were not sure that it was the right explanation for what we were seeing.

We looked more closely at dirty sponges. Under a microscope it was clear that most of the dirt was stuck to the outside surface of the sponge. We concluded that mops also worked by the adhesion of dirt to a cleaning surface. And then we recognized the second contradiction: the better a mop was at grabbing dirt off the floor, the more difficult it was to clean the mop itself.

From this process of ethnographic fieldwork and studio- based analysis, a clear set of design requirements emerged. We were looking for a solution that:

- Works for both sweeping and mopping;

- Does not require you to clean the broom or mop after cleaning the floor;

- Is clean to use and doesn't make you want to wear old clothes;

- Is quick and fun so people want to clean more and can have cleaner homes.

Get into that anthropological mindset and explore what your audience is currently doing. From their current behavior, and gripes, you can extract pain points to address with your content. Maybe you’re not about the reinvent the floor mop, but you should have the same approach as those researchers: figure out what’s really going on in your targets’ lives, and break down their problems.

Bear in mind that what people say in direct response to your queries is less meaningful than what they say spontaneously, and behavior is more important than both. To quote The Mom Test, by Rob Fitzpatrick:

The world’s most deadly fluff is: ‘I would definitely buy that.’ It just sounds so concrete. As a founder, you desperately want to believe it’s money in the bank. But folks are wildly optimistic about what they would do in the future. They’re always more positive, excited, and willing to pay in the imagined future than they are once it arrives.

Greg Foster of Graphite read The Mom Test and realized that he needed to think about his potential customers’ feedback differently:

When I used to share my excitement about our iOS rollbacks concept, the usual response was overwhelmingly positive, but in hindsight it was probably just folks being nice to me.

Of course, my friend would tell me, “iOS rollbacks sound like a great idea!” But what I should have asked was:

- “When was the last time you googled for a way to roll back your iOS app?”

- “Did you try the answers online?”

- “You’re a great engineer, tell me about how you’ve hacked a solution here.”

- “Given that you’ve hacked a solution, do you still google from time to time for something better?”

The key is to ask questions that dig deeper, inquiring about actual behavior, like whether someone has ever actively sought a solution like yours.

Okay but wait, aren’t we talking about a free download of some kind? A lead magnet doesn’t mean selling anything. Well… yes and no. I said above that people love free stuff, and that’s a big part of why lead magnets are so effective. Still true!

But at the same time, you kinda are selling your offer. It’s just that the price is an email address. You still need to offer something valuable to make the trade.

For more, read “How do you create a product people want to buy?” from business coach Amy Hoy. Notice the ways Amy uses the sales psychology that she describes on you.

The Magnet Itself

Once you’ve figured out what subject to focus on, it’s time to think about format. There are many different types of lead magnet:

- Ebook

- Video course / training videos

- Whitepaper / research report

- Case study

- Template

- Cheatsheet / reference guide

- List of ideas / swipe file

- Quiz result

- Early access

- Community chat or forum

- Anything else you can come up with!

As for how you present the lead magnet, it can have its own landing page, or be integrated into a blog post or article. Digital marketing guru Neil Patel recommends the “content upgrade” tactic, which doubles down on whatever information the reader is already perusing: “A lead magnet sweetens the pot by providing additional insight on the same exact topic they were reading about.”

Author Lead Magnets

Sci-fi author Ryan Williamson uses BookFunnel to deliver a free download his novella Land of the Black Sun, which he promotes to his followers on X:

The free novella is positioned as a “welcome gift” for joining the newsletter.

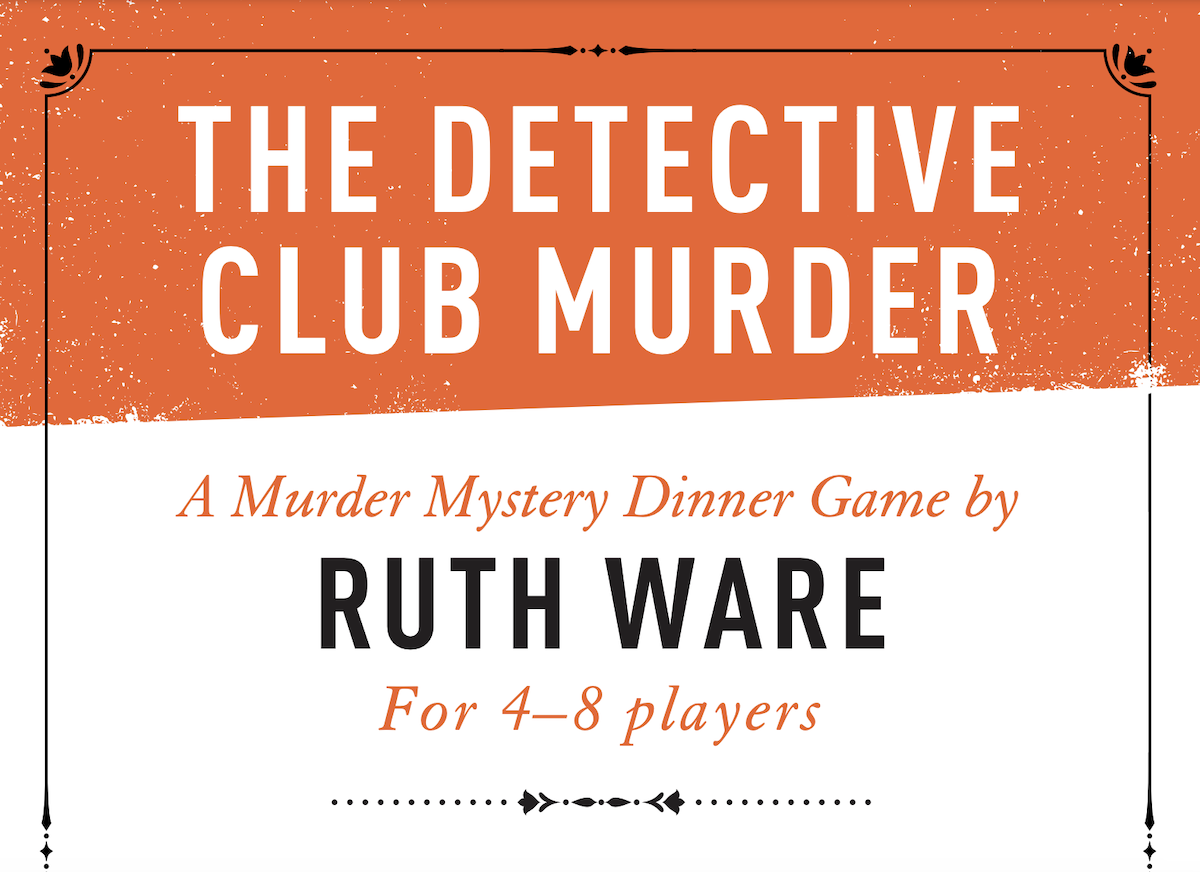

Bestselling novelist Ruth Ware writes psychological thrillers. On her website, she offers a free murder mystery party game called The Detective Club Murder:

Interestingly, The Detective Club Murder isn’t gated at all — you don’t need to sign up for anything to get the download. Presumably Ware has decided it works the best when people actually play the game together. She has pre-packaged an experience that her devoted fans can use to create new ones.

This brings up an important point: What if people share the lead magnet after downloading it? That’s a good thing! It means you created something genuinely useful. Just make sure your information is included in the file so you’re easy to find. Notice the size of Ware’s byline on the first page of the game guide:

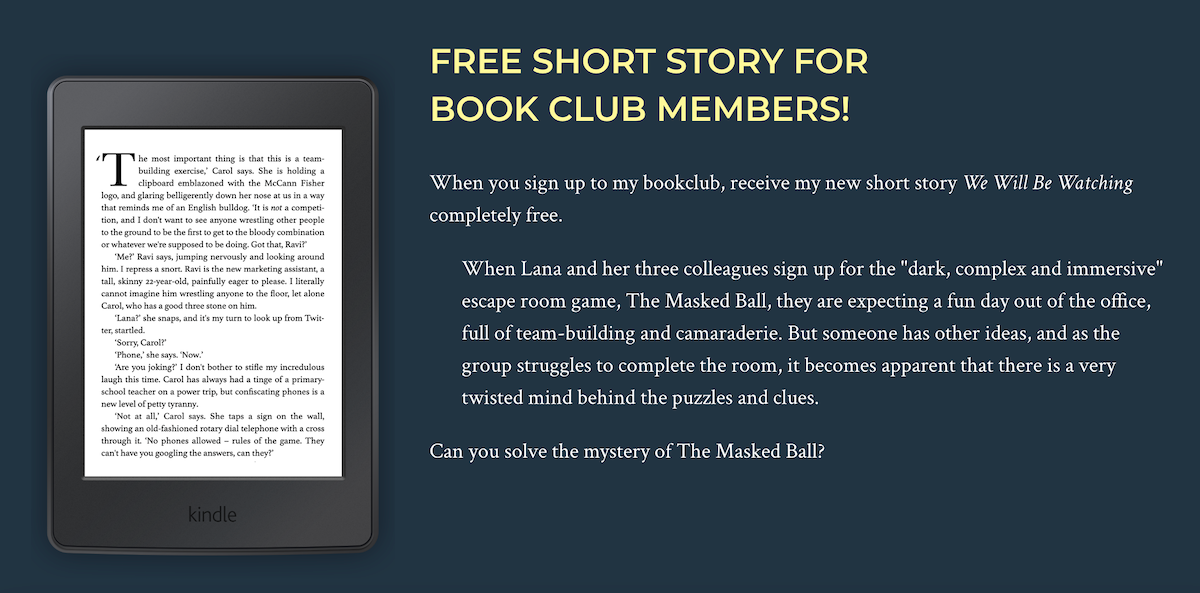

Ware also uses a more conventional lead magnet to invite newsletter subscribers — a free short story:

She also pitches the ongoing rewards of joining her newsletter.

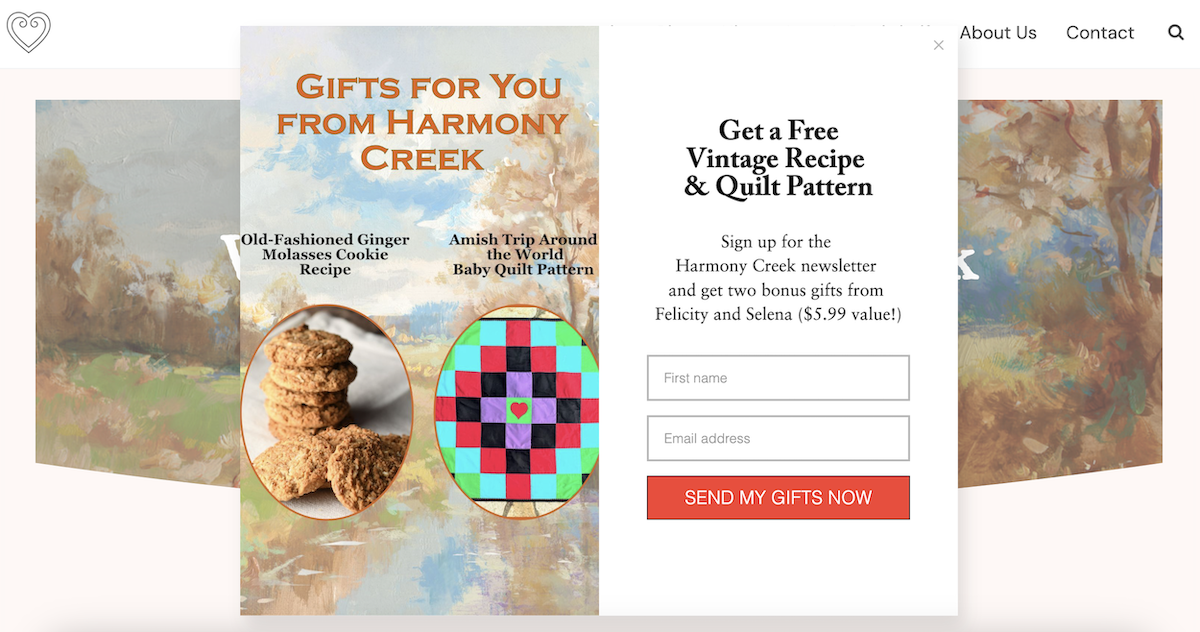

The lead magnet for an author newsletter doesn’t necessarily have to be literary. Felicity and Selena Wilder offer a cookie recipe and a baby quilt pattern to promote their Harmony Creek pioneer romances:

The idea is that the type of person who reads cozy historical romances likely also enjoys baking and crafting.

Need more examples to inspire you? There are tons of lead magnet guides competing on Google, and I read a bunch of them to prepare for writing this post. I think these four are the most useful:

- “How to create a lead magnet that converts”

- “20 Eye-Catching Lead Magnet Examples [+Tutorial]”

- “Lead Magnets Explained: Definition, Basics & 17 Examples”

- “How to Create a High-Value Lead Magnet in 30 Minutes or Less” (warning, the “30 Minutes or Less” claim is ridiculous but otherwise this is a decent rundown)

Bonus: Every single one of those articles contains a CTA asking for your email, to remind you how it feels to be the target 😉

Speaking of CTAs…

Call To Action

The call to action is when you say, “Enter your email to get 24 scrumptious dumpling recipes!” Tell the reader what you want them to do, and why it will benefit them.

Here is where you emphasize the value proposition of your lead magnet. Distill its purpose into a sentence, focusing on what your prospective subscriber is trying to accomplish. Be specific.

Consider a few possibilities:

- 24 scrumptious dumpling recipes to impress your dinner party guests.

- 24 scrumptious dumpling recipes to meal-prep healthy lunches for your work week.

- 24 scrumptious dumpling recipes with easy step-by-step instructions for new cooks.

- 24 scrumptious dumpling recipes to make in big batches, freezer-friendly.

- 24 scrumptious dumpling recipes to feed your picky-eater kid.

In theory, these could all be the same 24 recipes. But the best pitch for downloading them depends on who you’re trying to reach, and the problem you’re trying to solve for them.

What if you’re trying to reach newsletter writers who want to grow their audiences? You might publish an in-depth explanation of how lead magnets work and how to create a good one, and then ask for their email address to get the full guide.