You know, generally, how telegraphs and trains work. And that means you already have all the pieces for the origin of the word “online.” You just need someone to connect the dots between the telegraph lines that ran alongside 19th-century train tracks and the signals they would send ahead to let stations there was a car “on the line.” Take that to your next happy hour!

The idea that you have hundreds of these connections lying dormant in your brain, waiting to be pointed out, is what makes slang and the etymology surrounding it so darn enchanting.

Sure, the histories of a great many words are much more academic and archaeological, with centuries-old linguistic roots. But as many times as not, they’re closer to someone handing you a treasure map of your own backyard. Shallow digging on familiar ground and a helluva conversation starter.

In the beginning was the word

The early internet was a predominantly text-based medium flooded by people searching for ways to communicate and connect with culturally and physically distant others. Their language is still fresh and accessible, driven by events and context that are still tactile and textured, unlike so many common words with ancient roots that ”once they are in common use, quickly become mere sounds, their etymology being buried, like so many of the earth’s marvels, beneath the dust of habit,” as Salman Rushdie put it.

Tech slang is also plain old playful, typically invented by young hackers who compulsively broke and repaired things (including language!) solely for the fun of it.

Image via Wired, The Tech Model Railroad Club

The word hack itself was borne from MIT’s Tech Model Railroad Club, which published a dictionary of the group’s lingo in 1959. Long before a hack was related to anything criminal or nefarious it was “something done without constructive end; an entropy booster.” And the preface to the group’s book of colloquialisms notes that “The Dictionary was intended to be humorous. Each entry was thought to be funny: some are puns, some are irreverent reflections on TMRC culture, and a few are more or less straight definitions that seemed amusing to me in their own right.” The Dictionary, indeed, was itself a hack.

From that point onward, neologizing became a fundamental part of hacker culture, with TMRC’s spiritual successor The Jargon File romanticizing in Chapter One that, “Hackers, as a rule, love wordplay and are very conscious and inventive in their use of language…[They] regard slang formation and use as a game to be played for conscious pleasure.” It was a pastime predicated on the participation of others.

The Jargon File’s Glossary is stuffed to the gills with hastily conjured portmanteaus and playful coinages:

- Barfmail

- Gonkulator

- Mojibake

- Quux

- Veeblefester

These and hundreds of others helped hackers “hold places in the community and express shared values and experiences” whether they took place in USENET forums, BBSes, or email groups.

The words that bind us

In some circles, etymology can end up becoming a shibboleth, a sort of hall pass or club card, knowledge that doesn’t directly imply proficiency so much as familiarity.

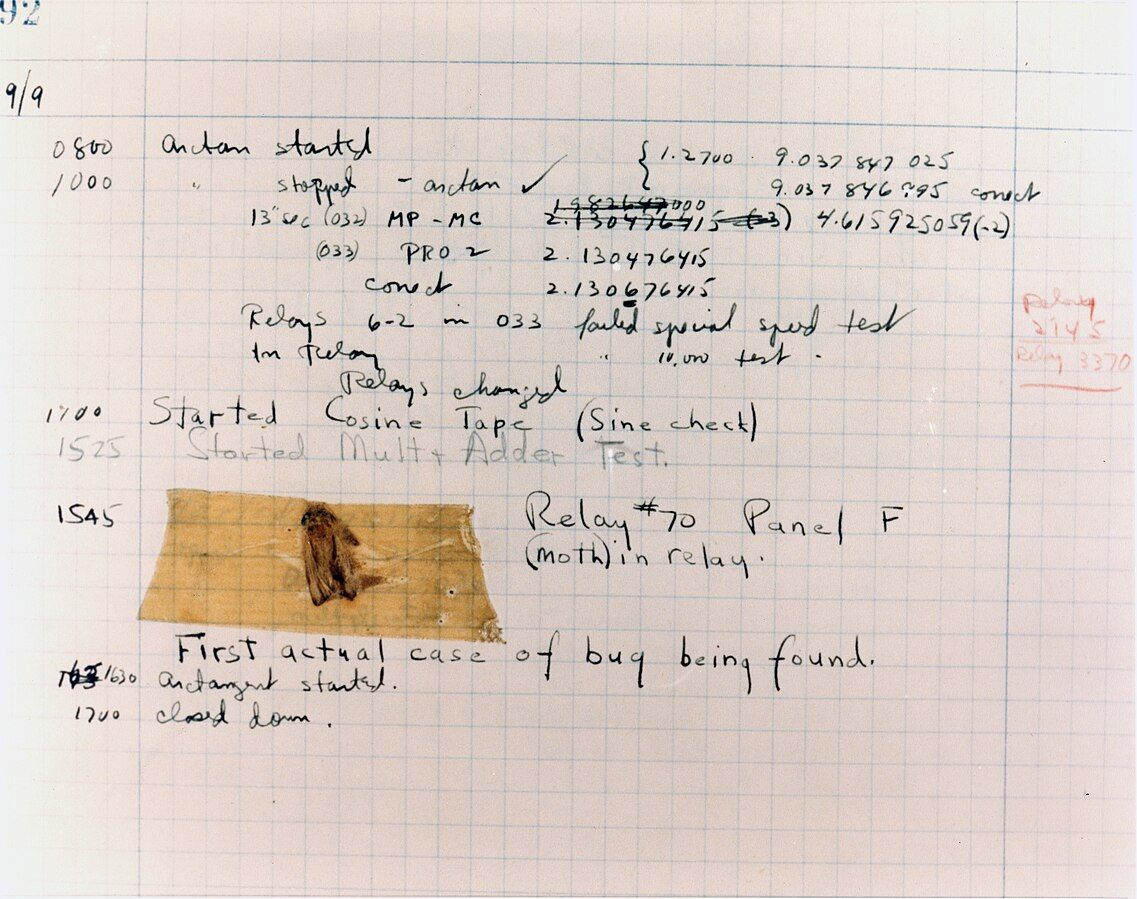

A junior software developer might score points with a senior programmer by referencing how computer “bugs” are labeled as such because a moth fried the relays inside the Harvard Mark II in 1947. Or that the word was used in similar ways almost 70 years earlier by Thomas Edison. In many cases, technical words created by technical people don’t require any specialized background!

Patched software tape via Gridinsoft

Even if you’ve never held a punch card in your hand, you can grasp the heritage of the word patch, in which old-school programmers glued physical patches over the original punched holes to update the “code.” And anyone who took physics in college will understand the connection between computer daemons (“background processes which work tirelessly to perform system chores”) and Maxwell’s daemon from thermodynamics.

“A group needs to bond. It needs to form its identity and it does this, online especially but generally too, through language,” David Crystal commented in an interview about internet linguistics. Sometimes, a group grows large enough that its language becomes trite or cliche. Other times, there’s no upper limit, as evidenced by hacker neologisms that became universal language and brought disparate groups together.

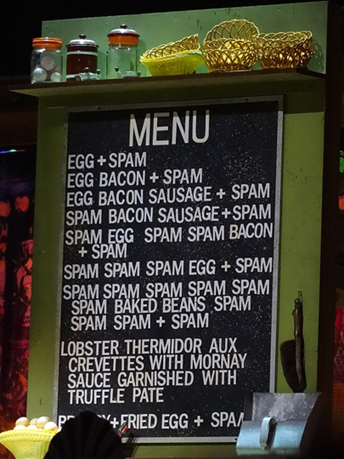

The genesis of spam, for example, came sometime in the late 80s. Internet lexicographers like Brad Templeton document multiple claims about its first appearance, ranging from so-called multi-user “dungeons” to AOL Star Trek chat rooms. No matter the case, it always began as a reference to the Vikings’ repetitive and unsolicited Spam Song from an early Monthy Python sketch. Today it’s a thing all its own. Countless people who have never seen the sketch or know how spam email got its moniker use the word every day to subtly indicate to others that they hate it too, that they share the same annoyance.

“To utter a posting on Usenet designed to attract predictable responses or flames,” or to troll, is another internet blight whose etymology is hard to trace. While it’s generally agreed that the original use was a reference to fishing (only later taking on a double meaning that also referenced Scandinavian folklore), there are several claims that it goes back further than the OED’s earliest attribution of the term to alt.folklore.urban.

Like hack, troll started off far more benignly than its current form. It was a way for senior members of a group or forum to build rapport with each other over the predictable behavior of non-senior members. For me, knowing its playful origin helps to disarm its current toxicity somewhat. As Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in The Poet, “The etymologist finds the deadest word to have been once a brilliant picture. Language is fossil poetry.”

The importance of inventing words

Slang isn’t always a matter of retrospective significance. Hacks, bugs, patches, spam, trolls, they all had to be written hundreds of times before their newest definitions were accepted. But Claude Shannon's combination of “binary digits” into “bits” took hold almost immediately. Ward Cunningham’s naming of his user-editable website model after Honolulu Airport’s wiki wiki shuttle gained popularity quickly. And Richard Dawkins’s invention of the word meme was widely accepted soon after The Selfish Gene was published.

These were individuals with interesting ideas and audiences. Tech Model Railroad Club lingo worked because it was used between close friends, in the same way that The Jargon File’s glossary relied on the internet’s earliest, most fervent communities. These were shared experiences, totally antithetical to having a follower list of 1,000 people who may or may not see your word.

Emerson said that “every word was once a poem.” And you could just as easily say that internet slang was once an inside joke in a USENET forum, or a recurring segment in a weekly newsletter, or an editorial guideline in wiki.

You, too, can coin terms. Go ahead, start a club. Put some words in the ground for others to dig up and share.

Header Image by oliva732000 via Wikimedia Commons