The first double opt-in email was a chatbot.

The year, 1993. The internet, 16 months old. The first spam email was sent 15 years earlier, but the spam in reference to email wouldn’t enter the public lexicon for another month.

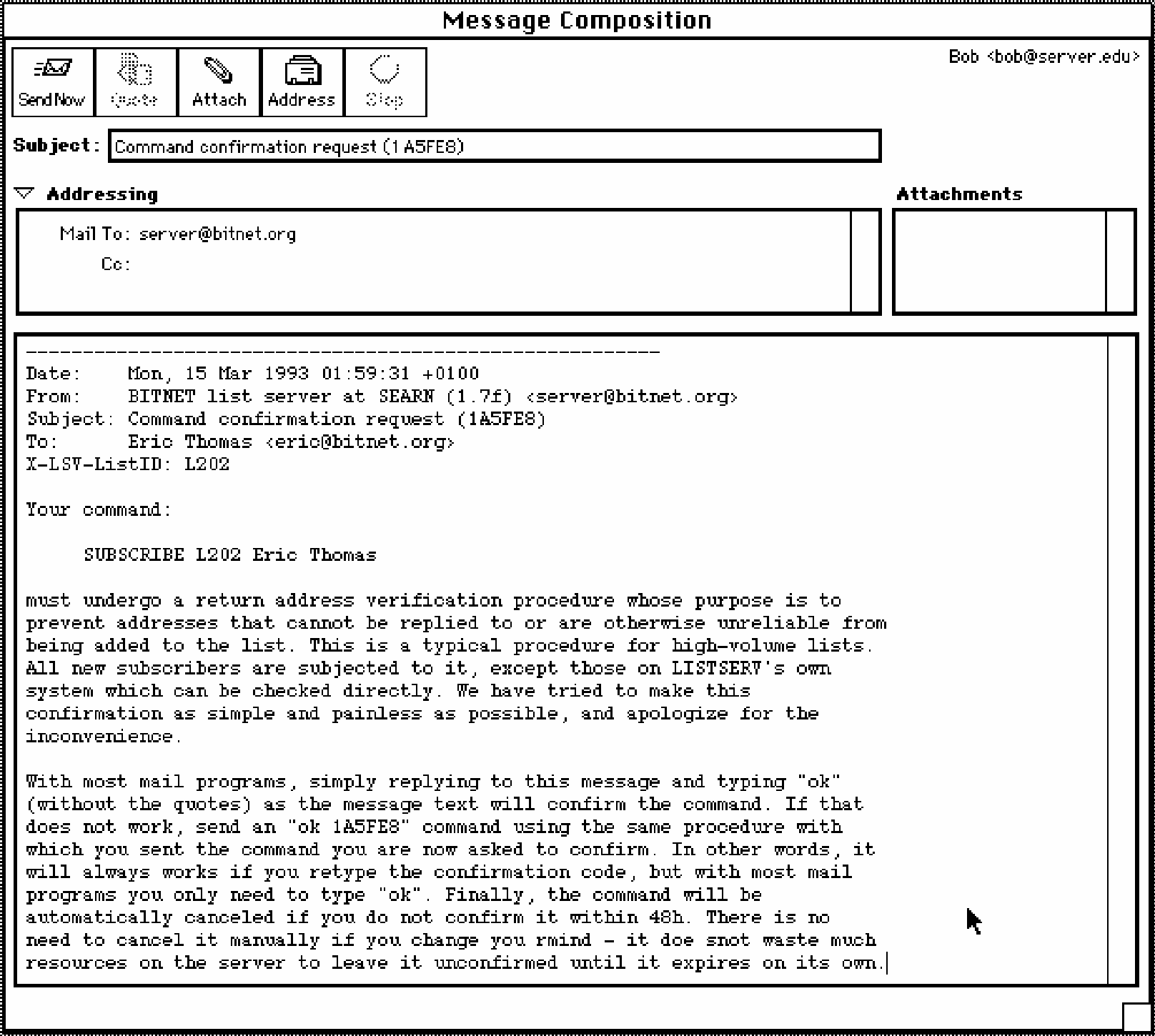

That’s when LISTSERV, one of the original email list tools, added a feature that’d become a defining email subscription feature. Moments after subscribing to an email list, you’d receive an email like the following:

“Your command: SUBSCRIBE LISTNAME Firstname Lastname must undergo a return address verification procedure. With most mail programs, simply replying to this message and typing "ok" (without the quotes) as the message text will confirm the command.”

Reply ok, and the server would read your message, automatically confirm your subscription, and start sending you emails. Thus began the email feature most email operators would assume keeps them CAN-SPAM and GDPR compliant.

Only it wasn’t invented to prevent spam. That was simply a happy accident.

A chatbot admin on the first social network

On early networked computers, electronic mail was the internet, social networks, and chat rolled into one. Emailing individuals was useful enough. Mailing lists, with every message and reply echoed out to everyone else on the list, added vitality. Suddenly you could make new friends and influence people without leaving your office.

Or, you know, start a fight. “People started flamewars, and they started calling each other names, and the traffic spiked,” recalled LISTSERV creator Eric Thomas, eerily foreboding of social networks and the internet’s accidentally perverse incentives to stroke drama.

Facebook can afford to let comment wars rage. But in email land, more people meant more management headaches. Managing a mailing list, in those days, was manual. People would email asking to be added to a list, to be taken off the list, to get their message shared around. It was a lot of painstaking overhead.

LISTSERV was built to automate the process. Everything you needed you could get the server to do you. Email it to ask to join or leave a list; reply to someone else’s message and it’d forward it to everyone else. The only human in the loop was you, the subscriber.

Only, email wasn’t very reliable, at the dawn of the internet. “Many burgeoning ISPs lacked the resources to help their customers set up their email clients,” recalled Thomas, “and it was not uncommon to get mail from addresses that you could not reply to.” And email lists relied on replies. Just as on social media today, communities wouldn’t be nearly as appealing—nay, addictive—without comments.

So on March 15, 1993, LISTSERV 1.7 added a command confirmation system. Whenever you asked the email server to do something, you’d get a reply confirming the command—the email version of Siri reading back a dictated message before sending it. Those confirmations were first used to make sure your email account was working as expected.

The feature was added as “a return address verification system for ... subscribers from unreliable networks,” read the announcement email. If the confirmation email bounced, or if the user never replied, the list manager could reach out personally to see if their email system was configured correctly.

The confirmation email grew over time. By 1996, it included debugging tips, and told recipients that “This is a typical procedure for high-volume lists and all new subscribers are subjected to it - you are not being singled out,” as though double opt-in felt like the email equivalent of an airport security search. And if your ok reply didn’t go through? “Please contact the list owner for help,” the docs suggested.

Are you sure you want to receive emails?

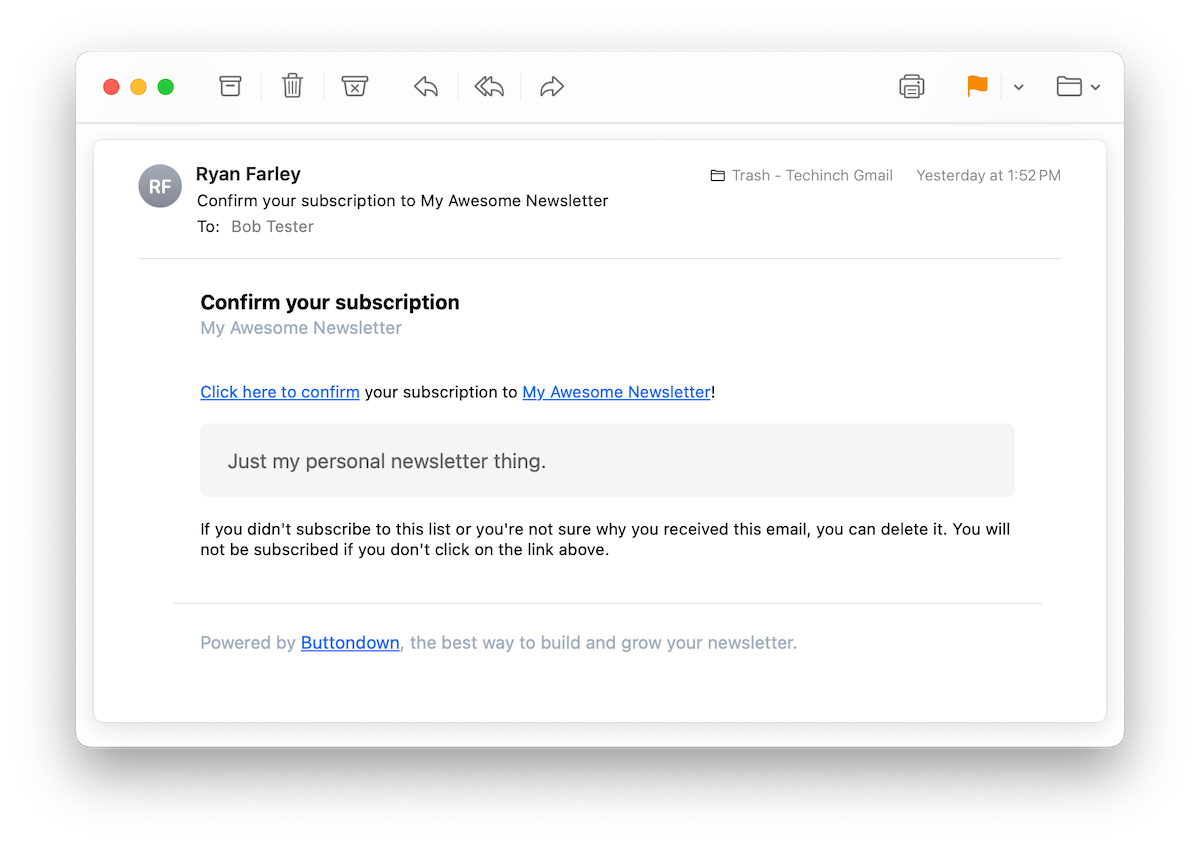

By the turn of the century, the internet had collectively dubbed “return address verification” as “double opt-in.” Some today insist on calling it “confirmed opt-in.” “Closed Loop Confirmed Opt In” is what the Spamhaus project uses.

Regardless of the name, the idea’s the same: When you sign up for an email list, the first message you receive asks you to verify that you signed up, and you’ll only receive subsequent emails if you follow through and verify. It’s a codified Golden Rule of Email, where you’ll only email people who want you to do so.

Yet uptake was slow, at first. Eleven years after LISTSERV’s first double opt-in implementation, only 5% of Fortune 500s used it. Marketers feared it was a roadblock in getting people signed up to your lists.

Aweber, for example, implemented double opt-in around December 2002—with the now-familiar option to click a link to confirm your email. They quickly found that “we get fewer double opt-ins,” as feared. Yet it was not all bad news: “The overall number of sales we receive from those follow ups is the same,” Aweber continued.

LISTSERV proved the same. By 2000, LISTSERV already powered an estimated 50,000 email lists with a cumulative 30 million subscribers. That extra reply or link click was a hurdle people were clearly willing to surmount—as long as they really wanted to receive your emails in the first place.

It was those higher interaction rates—more opens, more replies, fewer unsubscribes—that made double opt-in take off.

For, surprising as it may seem, even today there is no legal requirement for double opt-in for most emails in most of the world.

The US’ CAN-SPAM act requires opt-out: You must always include a way to unsubscribe from emails, and must remove people from lists within 10 days of their request. You must also track consent via a “verifiable opt-in action such as checking a box or some other affirmative action” for emails involving “sensitive data” such as health information, credit reports, or student data—but, again, just a checkbox technically covers it.

The EU’s GDPR is more prescriptive, yet it too doesn’t specifically require double opt-in. Instead, it requires you to prove consent to receive your emails—established, again, with a checkbox paired with a privacy policy for informed consent.

Google has interpreted that—and other local laws—to mean that double opt-in is required in Germany, as well as in Austria, Greece, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Norway. And what the platforms decree, the rest of the world follows.

“Legit email lists are supposed to be "double opt-in;" they are supposed to send you one message which contains a link you need to click on (or otherwise reply to) to be subscribed,” wrote @PaulHoule on Hacker News.

Not because they’re required to. Because, as he said, “People who send mail through an email deliverability service such as Amazon's SES or Sendgrid will get hassled if their bounce rate is too high because that's a sign they aren't maintaining their lists. A bounce is more effective than a spam complaint at pouring sand in the gears of the email senders and configuring your email server to bounce the messages would accomplish that.”

You’re better off getting fewer subscribers with double opt-in, and ensuring those who subscribe really want your messages. You might even do best with a LISTSERV-inspired flow, asking people to reply to your emails to prove there are real humans on the other end of your mailing list. Not for the law, but for the whims of spam filters, for whom your handcrafted newsletter can look a lot like spam for want of a double opt-in flow.

Opt-in communications and communities

Email survived, Thomas reminisced 35 years after his first LISTSERV release, because “email allows people to form communities, to share experiences, to share joys and pains with fellow human beings.” Yet those needs include the need to escape the noise, sometime, to go into your room and be alone. It includes the freedom of association, to choose with whom you wish to communicate, and to close your inbox to unsolicited messages.

Which is why double opt-in and one-click unsubscribe options are critical to email turning into today’s default way to publish online subscription content. It means someone can’t just add you to their list without your knowledge (and if they do, you can mark their message as spam and never see followup emails again). It means you can join lists, then leave if you’re not interested. It means you can start a list of your own and confidently email people who opted in, without worrying about spam regulations.

“Of course, we didn’t have spam back then. That was the good thing,” said Thomas. But his double opt-in? It was a weapon to start fighting spam, before it kicked off in earnest.