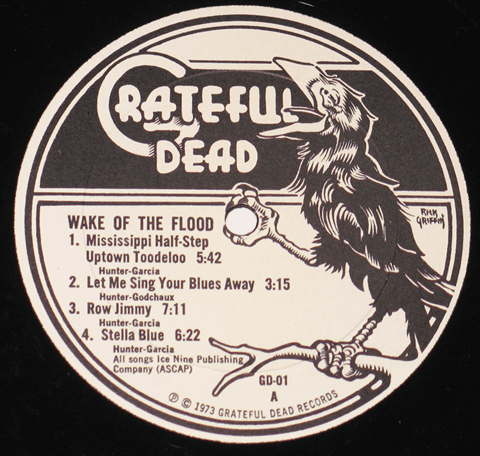

The Grateful Dead, that paragon of 70s counterculture, didn’t set out to inspire the CEO of a CRM software company and an NBA star to write a book about marketing. And yet, here we are.

That’s not to say that Brian Halligan et al are exploitative opportunists. They seem to be genuine “family members,” in the parlance of The Dead. But maybe we don’t have to turn every success story into a framework, a case study, a template, an optimization, a workflow, a piece of content (says the guy writing a blog post).

Maybe the band’s unorthodox newsletter, their championing of peer-to-peer tape-sharing, and their prioritization of live shows over record sales should be nothing more than a reminder to stop obsessing over perfect promotion and simply do what you want.

Maybe, just maybe, The Grateful Dead were a phenomenal jam band whose success, like so many newsletters today, had nothing to do with “marketing” at all.

Let him cast a stone at me, for playing in the band

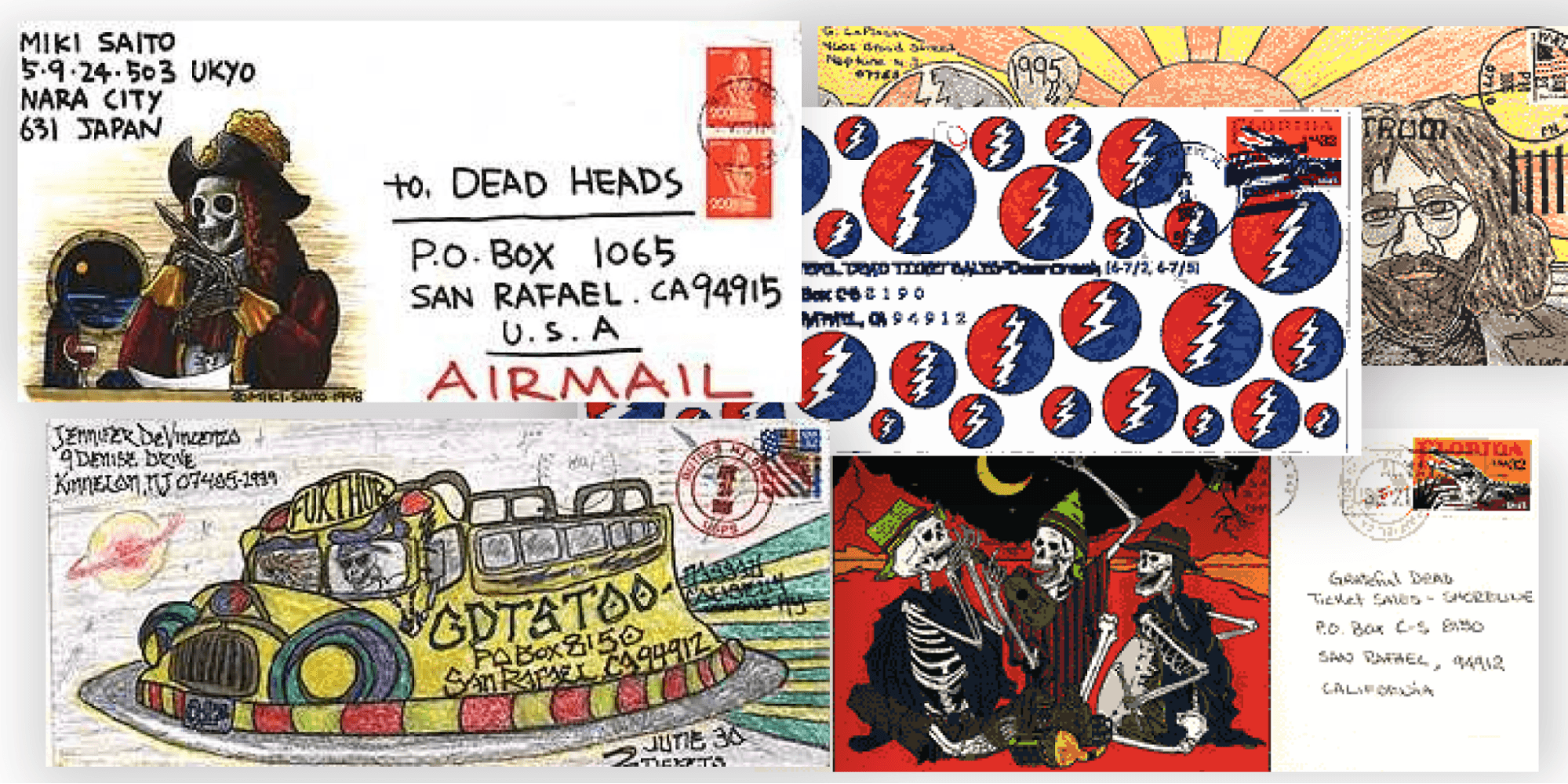

A lot of gurus (and HubSpot CEOs) will argue that marketing is a sort of bamboo finger trap, something that you have to do by not doing it. That more than ten thousand Grateful Dead fans responded, in 1971, to a printed insert in their self-titled (or Skull & Roses) record because there were no ulterior motives.

Album insert via Dead.net

The band’s first newsletter, the one that went out to everyone who responded to those three questions, read “If we had it really super together, if we had a lot of money, what we could have done was to organize like rough lists of members of the Grateful Dead weirdness scene or whatever, and have them get together in their town and put on some trips or something.” All they wanted was to get everyone together for a good time.

That first issue reads like a sermon from the authenticity gospel: “Do right by your audience and you’ll succeed.” But that trades happy accidents and long strange trips for illusions of control and meritocracy. It denigrates all the artists who produced beauty, did right by their fans, and did not succeed. The reasons that a creative effort catches fire or dies out often have everything to do with being in the right place at the right time, and nothing to do with marketing.

The Grateful Dead weren’t strangers to provenance, helped along in their early days by Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests, and later by fans who would return from concerts to their day jobs, in Silicon Valley.

Sometimes the songs we hear are just songs of our own

For every article or podcast calling The Grateful Dead marketing masters, there’s another claiming that they “built the internet” or “invented Silicon Valley.” Get any further than the headline, though, and what you find is that it was their fans who were early adopters and terminally online as the internet was taking shape.

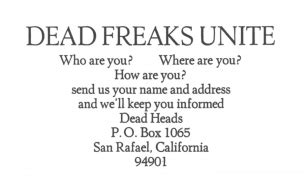

Image of Paul Martin via Wired

“As we are far from being mechanized or computerized, (all manual labor as it were) you may find us slow in returning your letter,” the band’s 1971 newsletter read. Then, another issue in 1972 included an update that “We have even received a personal letter written by a computer - - - we almost attempted to write a letter back but no one was versed well enough in computer language to carry it off.” Tech-savvy fans, however, were happy to carry the torch.

Paul Martin, a graduate student at Stanford’s Artificial Intelligence Lab (SAIL), created the dead@dis mailing list 1973, on his university-issued PDP-10 computer. Others in the lab set up automatic filters that flagged messages about music or The Grateful Dead from anywhere on the network. Almost all of the SAIL Dead Heads added half-remembered lyrics to shared computer files.

When Phil Lesh, the band’s bassist visited SAIL and Paul showed him a printout of their crowd-sourced lyrics database, Lesh supposedly said “Oh, this is great. We don't have all this shit written down anywhere.” This, in the same year that they played 72 shows and their mailing list had ballooned to more than 25,000 subscribers.

The Wall of Sound via All This Is That

Like their shows, the cadence and content of The Grateful Dead’s newsletters were capricious and seemingly improvised. There were instructions for mail-order tickets one month, LSD-fueled hypnocracy sketches the next, and diagrams of their infamous 600-speaker “Wall of Sound” after that. They did not, it seemed, have a grand plan or long time horizon. They weren’t overly interested in selling more merch or playing larger shows.

“The megagig form is sort of bankrupt; devoid of dignity for either the listener or the player,” they explained to fans after a spat of large-venue shows. “The fact is the Dead won't go out again unless the situation is groovey.” They didn’t even send updates to their entire mailing list, opting instead to contact only the people living wherever their next show would be.

Ship of fools, sail away from me

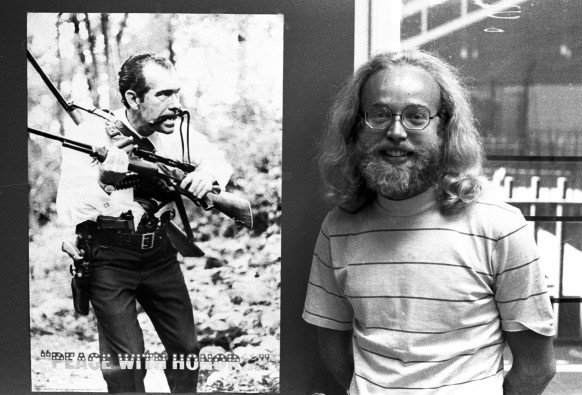

When marketing was mentioned, it was a thing to be wrangled, controlled. “We've planned for a year to form our own record manufacturing and distributing company so as to be more on top of the marketing process.” This, justified by a promise to “Package and promote our product in an honest and human manner, and possibly stand aside from the retail list-price inflation spiral.” Marketing, to them, was a thing that must be subjugated in service to the fans.

The first album pressed by Grateful Dead Records via Vinyl Records Gallery

Thousands of responses flooded in, mostly from fans asking how they could pitch in. “I hearby volunteer my humble services for the legions of the "Dead" in their noble task to free the ship of artistic freedom from moorings of the large corporate hydra…It will be a pleasure to work for someone with an idea worth believing in,” one wrote. “My interpretation of the "Grateful Dead" is that they are a medium of message and a promise for tomorrow fulfilled not narrowed Into a cell of commercialism,” another wrote.

And when they soon saw firsthand how quickly the corporate hydra regrew its severed heads, how slaying it got in the way of creating and playing music, they handed over distribution to United Artists. “Our full attention can return to music and recording…It is with a sigh of relief we shake off perpetual business hassles.” And they did.

In the late 70s, The Grateful Dead continued to prioritize small venues, essentially skipping any promotion that wasn’t notifying newsletter subscribers when a nearby show was happening and providing a way to mail-order tickets. They had 63,000 names on their mailing list by 1976, after all.

A taper’s pit for a Grateful Dead show via Red Clay Soul

Even the most high-minded bands would have been tempted to use that trove of contact info to move more records. Instead, The Grateful Dead encouraged fans to tape live shows, as long as they didn’t turn around and sell them for profit. It was a move that would eventually form the basis of the Creative Commons license. The band even made sure that every venue included a designated place for “tapers.” This particular brand of fan would return home, log onto BBSes and USENET, and offer to swap their tapes.

“Instead of 1 person making 100 copies, maybe 5 people (using high quality equipment) could each make 20 copies to ease the load a bit,” Garry Hodgson posted in rec.music.gdead. Within a year or two, so-called Tape Trees were common practice. A seeder would offer five copies to the first five responders, as long as those responders made and passed on five copies of their own. Eventually, Furthernet, an early take on the idea BitTorrent perfected, would apply a similar philosophy for file-sharing.

Tape Trees were not a product of the band but the fans. They were not a metric to be measured and A/B tested. “The music is for the people, you know,” Frontman Garcia preached in a 1981 hotel room interview. “It’s like after it leaves our instruments it’s of no value to us. So it might as well be taped.”

Winds both foul and fair all swarm

It would be disingenuous to say that The Grateful Dead never thought about making more money or growing their fanbase. They did. But they’d almost certainly prefer that, rather than be associated with the genesis of “content marketing,” their legacy is one of wingin’ it. That people remember them for jamming, whether that was on stage, pressing their own records, or writing newsletters with little rhyme or reason.

Go ahead. Send at random intervals and times. Turn off click tracking or ignore your analytics for a while. Stop reading marketing gurus. Or, as The Dead sang on track 5 of Blues for Allah, the last studio album they distributed themselves, “Gone are the days we stopped to decide, Where we should go, We just ride.”

Header image via GDTS TOO’s archive of mail-order ticket envelope art