Collin’s Law deserves to join the likes of Moore’s and Conway’s Laws. In 2014, CEO of Front Mathilde Collin wrote in a guest post for Intercom, “Every tool that sets out to kill email ends up sending it instead.” It was a pointed response to founders from Facebook, Salesforce, and Asana, among others, who declared email dead or dying around the same time. And, as far as I can tell, Collin's Law still hasn't been broken in the past decade.

Doubts surrounding email’s staying power date much further back than Web 2.0, though. Just for different reasons.

The ‘90s: Email is too complicated

Let’s start with John McCarthy–the creator of the original Lisp programming language–who predicted that fax would be more popular than email. “Unless email is freed from dependence on the networks, I predict it will be supplanted by telefax,” he argued in a 1989 Stanford editorial. Reasonable enough, considering that users need to dial into Unix-to-Unix Copy Protocol systems to send their messages.

UUCPs were not centrally organized and one user’s access point might have not reached the UUCP of their intended recipient. Even if they did, messages worked on a store-and-forward model, sent in batches at predetermined connection times. “To become a telefax user, it is only necessary to buy a telefax machine…and to publicize one's fax number on stationery…Once this is done anyone in the world can communicate with you.” Point-to-point instant written communication, over the phone line you already had.

It’s not exactly fair to say that McCarthy was declaring email dead, however. The first commercial Internet service provider had gone into business only a few months prior and getting an inbox still required choosing from a number of semi-isolated access points. “A whole industry is founded on the technologically unsound ideas of competitive special purpose networks and storage of mail on mail computers. It is as though there were dozens of special purpose telephone networks and no general network.” This wasn’t an issue after the Protocol Wars, when TCP/IP won and the modern internet emerged with email as its default communications sidekick. But there were still speedbumps.

A 1993 cover story in Byte magazine promised that Smarter E-Mail Is Coming, eventually. “An industry executive once quipped that there was no clearer sign of the failure of E-mail than the success of the fax.” Like McCarthy, Byte thought email would reshape communication only if it didn’t drown in the “alphabet soup of acronyms” and “gateways, switches, and battles over APIs.” At this point in tech history, proprietary email systems didn’t always work with other systems, and sending a message to someone outside your organization would often fail.

Four years later, the situation had only marginally improved. “Some companies have as many as five or six different e-mail systems, each with its own proprietary protocols and formats,” reads Byte’s 1997 cover story, Your E-Mail is Obsolete. “It is an enormous barrier to exchanging, archiving, and retrieving vital corporate information.”

Then came AOL, Hotmail, and Yahoo! Mail. Email became universal, interoperable, free, and declared dead for reasons that were antipodal to those proposed by McCarthy and Byte.

The ‘00s: Email is only for spammers and grandparents

The more ubiquitous it became, the easier it was to abuse email. Journalists were quick to capitalize on the junk mail epidemic. “Now email is a crushing tsunami. The average corporate email account receives 18 MB of mail and attachments each business day,” a 2007 Fast Company article said, one of the earliest headlines that declared Email Is Dead.

Pointless threads and spam weren’t the only justification, either. Numerous surveys in the late aughts pointed to how much younger generations preferred instant messaging and social media over email. That, it seemed, was enough to get their elders to reconsider the whole enterprise.

Slate’s The Death of E-Mail was published a few months after Fast Company’s article. “You could chalk up the decline of e-mail to kids following the newest tech fads…I've come around to the idea, though, that all of this other stuff is catching on because e-mail isn't perfect…Colleges have already thrown up their hands and created Facebook and MySpace pages to stay in touch with students.” Email might live on in the workplace, but only begrudgingly.

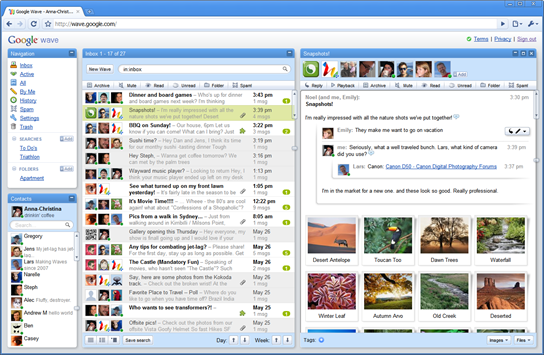

Jessica Lessin, who would go on to start The Information, doubled down in her 2009 Wall Street Journal article. “Email has had a good run as king of communications. But its reign is over.” She believed it was too slow. You had to manually refresh your inbox. The audacity! “Email, stuck in the era of attachments, seems boring compared to services like Google Wave, currently in test phase, which allows users to share photos by dragging and dropping them from a desktop into a Wave, and to enter comments in near real time.”

While mobile push email notifications came to the iPhone mere months before the WSJ article, the damage was done. Founders saw it as an opportunity.

The ‘10s: Email should do more

If email wouldn't die of its own accord, a new generation of founders set out to kill it. “E-mail–I can’t imagine life without it–is probably going away,” Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg announced in a 2010 presentation. A few months later, Mark Zuckerberg quipped “We don’t think that a modern messaging system is going to be email,” during an overhyped Messenger release that later involved giving users Facebook email addresses.

These prognostications, along with those in the aughts and 90s, always come with caveats. After Zuckerberg’s comments, Big Think published Email Is Dead. What’s Next?, which, hilariously, begins its second paragraph with “Email is growing, to be sure.” That’s followed by research claiming one billion new addresses will be registered within four years of publication. No bother, said Microsoft’s head of Envisoneers, “Email is dead when it comes to social media in the same way that snail mail was dead when it came to email.”

This novelty bias was rampant during social media’s golden years. “Email was just meant as an upgrade of the post office. We’re using it for a complex action for which it just wasn’t intended,” one of Asana’s co-founders used to say. Never mind that it’s one of my favorite examples of Collin’s Law, with Asana currently offering users 22 email notification options and the ability to send tasks to their boards via plain text emails.

“Email is not social. Email is where good ideas go to die,” Hootsuite CEO Ryan Holmes said in a 2012 Fast Company article. “Brilliant messages race across the Internet at light speed only to end up trapped in an inbox.” Inboxes that Facebook, Asana, Hootsuite, and others cannot analyze, alter, read, reorder, redesign, or advertise in.

Arguably the most egregious of all the email naysayers, though, was Marc Benioff. Sales teams live and die by email, the most universally acceptable channel in the professional world. Salesforce, still a CRM at its core, exists to collect, archive, and mine email. And yet, in 2013 he went on stage at CES and announced “How are you connected with your customer, your partners, your employees. Email? Those days are over.” Twelve years later and there are over 1,000 email-related add-ons in Salesforce’s AppExchange directory.

Silicon Valley founders have since backed down on the death of email, faced with data that’s impossible to ignore. Mailchimp announced in 2014 that it was sending more than 10 billion emails per month before being acquired by Intuit for $12 billion in 2021. Substack was valued at $650 million. Twilio SendGrid (part of Buttondown’s stack!) joined the NYSE after sending 1 trillion emails.

The holier-than-thou attitude persists. Slack’s Stewart Butterfield called email “the cockroach of the internet,” in a 2015 Business Insider article.

But email was never a problem, much less a pest. Butterfield and others didn't hate email so much as the ways people used it. Just like Slack isn't the cause of distracted work, merely a misused vehicle of it. We just had to test-drive some email alternatives to finally realize how good we had it all along.

The ‘20s: Email is great the way it is

I could argue that newsletters saved email. That they were the salve that helped us recover from walled gardens and algorithms. But that, like so many founders quoted earlier, would be presumptuous.

“Email isn’t going anywhere, and it doesn’t need anyone to ‘save’ it. Trying to do so would be like giving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to an elite athlete in perfect health. It might be fun, but it’s not necessary,” Dave Pell joked in The Atlantic. “Sure, people complain about having too much email. But compared with everything else online, your inbox is the Walden Pond of the internet.”

I’m ecstatic that Calendly, Teams, Zendesk, and so many others are reducing the number of sent emails. My inbox is more fun than it’s ever been before. There are pop-up newsletters, modern-day zines, and marketing emails that actually interest me!

Email is unlike any other communication channel we have. I, for one, hope it never dies.