Phoning it in

Neither showing nor telling

I don’t like it when I have to read a character’s text messages in a TV show. It’s lazy filmmaking. It’s lousy storytelling. It’s a crap way to reveal character. It’s a shit way to advance the plot. TV is a show-me medium. I shouldn’t have to read tiny text on a phone screen while an actor does their best to hold it still in front of a camera. That’s not showing. It’s not even telling. You’re making me read your exposition. I don’t mind participating in a story. I don’t mind joining a few dots and feeling clever as a result. That’s immersion and it’s rewarding. But reading texts on telly is different. It’s loading work onto me, the viewer, that you, the filmmaker, should be doing. It’s abdication. Worse than that, it puts the story on hold. Time stands still while I read in text-speak words what should have been revealed by moving-picture action or dialogue. All narrative momentum is lost. Worse than that, you’ve literally and figuratively lost a dimension. What should be the job of three-dimensional characters is outsourced to a two-dimensional mobile phone. No shit your story goes flat as a result. Exposition by SMS or WhatsApp is a sure sign of substandard drama. If you do it early in a first episode, I’ll probably go find something else to watch instead. Storytelling via mobile phone is a “poor” signal, a sure-fire signal of poorness.

But, you say, mobile phones dominate our lives and so it’s natural that they should also dominate the lives of the characters in contemporary dramas. That makes sense on the face of it, but it makes for rubbish TV. It’s a culture clash, in that being true to modern culture clashes with the principles of good telly. So please don’t phone it in, even if that’s what your character would do in real life. I give you full creative licence to NOT reflect our small-screen culture on the bigger screen of my TV.

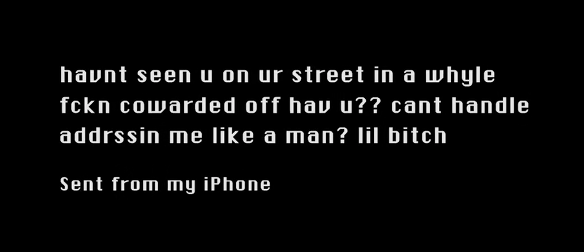

The wonderful exception to this rule is Baby Reindeer, whose episodes are peppered with “sent from my iPhone” emails from the unhinged stalker character, Martha. These texts are both funny and pathetic. They’re entertaining but they also provide disturbing insights into her state of mind. In this case the medium is part of the message. The use of text as a delivery mechanism isn’t a lazy cop-out. Rather than losing a dimension, these emails add texture. And they’re a distinctive aesthetic motif for the show. Time doesn’t stand still for these messages, you look forward to them. And you don’t have to read them on a phone. They’re given room to breathe, full-screen, in white text reversed out of black, befitting their status as active storytelling devices rather than lazy, low-cost exposition.

Silly daddy!

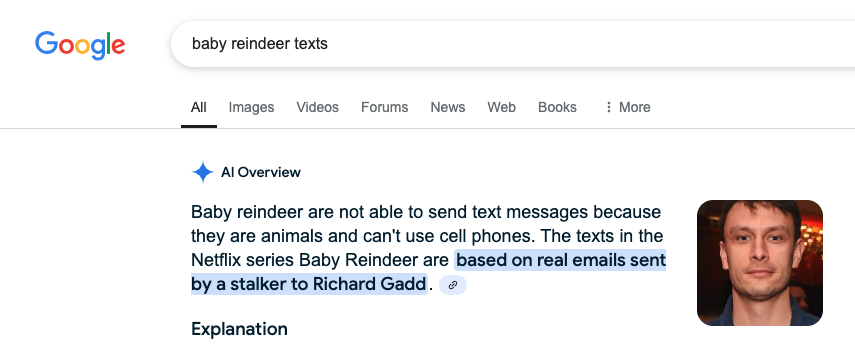

This (see the image below) is what I got when I searched for examples of Martha’s messages. The confusion of Google’s AI is almost endearing. It’s the earnest, oh-so-pleased-with-itself logic of a four year-old correcting a parent who’s said something that’s obviously stupid: “Silly daddy! Reindeer don’t have phones!” The AI should know better but it can’t trust itself to read the context of my query correctly. Maybe it’s because I used lower case letters for ‘baby reindeer’ and therefore it has to cover itself by giving the silly daddy answer as well as the correct one. Anyway, this, thankfully, is what we’re up against. It’s reassuring. A human would have read the context without any trouble.

The intersection of the technological and the theatrical

One of the main benefits of writing is that it’s a good way to work out what you think. Anyone who blogs knows this. But writing is also a good way to wonder. For example, writing this made me wonder about the origin of the phrase, “phoning it in,” to describe a half-hearted effort.

I found this article by someone who’s done the research spadework for us. A newspaper review of a 1938 theatre show, whose set design had been stripped back to nothing, suggested that if the production were any more minimalist, that actors would “phone it in.”

Hence this quote from the article, which neatly explains my issue with using mobile phone messages for exposition. It’s an unhelpful intersection of the technological and the theatrical.

…tracing the origins of this expression tells an intriguing story about the intersection of the technological and the theatrical.

The moment of quickening

By the way, I’ve finally gotten round to reading On Writing by Stephen King, and you can blame the longer than usual paragraphs on him. “Gotten” is probably his fault too. It’s an Americanism I have a soft spot for.

I would argue that the paragraph, not the sentence, is the basic unit of writing - the place where coherence begins and words stand a chance of becoming more than mere words. If the moment of quickening is to come, it comes at the level of the paragraph.

Stephen King, On Writing

Intelligent Artists

So there I was hating on filmmakers using mobile phones as a storytelling device when I saw the latest OK Go video. It’s fabulous. Of course it is. They all are. In a world that’s frothing at the mouth about Artificial Intelligence, along come some Intelligent Artists to remind us what creativity is all about.

IA » AI

The video is a carefully choreographed collage of 64 mobile phones, each of which is playing a separate, single-take piece of film. The phones are manipulated by human people, all of whom have to press play with split-second timing for the ensemble to work. The result is the latest in a long line of OK Go magic tricks.

The video for A Stone Only Rolls Downhill

A real sense of joy about other humans in the world

It’s telling that OK Go’s “making of” video is produced and hosted by the Project Management Institute. The mobile phones are obviously digital devices, but the video is a triumph of human ingenuity and problem solving.

Our videos always start with crazy ambitious ideas. But anybody can have crazy ideas. the hard part is actually making them happen. And that takes a lot of people with really specific skills and really extraordinary talents.

Damian Kulash, Lead Singer, OK Go

A big part of admiring a work of art is admiring the artistry behind it. There’s the idea. And there’s the painstaking, skilful process to render it. This, for me, is a uniquely, sacredly human thing. Without the painstaking human artistry, there is no “work” in a work of art, especially if the execution is a feat. And this is a big part of why AI “art” feels flat, just like reading a mobile phone on telly feels flat. It lacks the vital human dimension. We connect with the artistry as much as we connect with the artefact. OK Go are intelligent artists. Painstaking artistry is their aesthetic. Painstaking artistry is their MO. Dare I say it’s their irresistible truth?

We invested all this time and effort into this so that you could have three minutes of wow in your day, and a real sense of joy about other humans in the world. That’s a very precious commodity.

Damian Kulash, Lead Singer, OK Go

To fully enjoy the art, you need be moved by the “wow” in front of you, and you need that sense of joy about the unseen human(s) behind it.

There are 439 names in the credits at the end of OK Go’s latest video.

The making-of video.

Not phoning it in

So I’m trying the first episode of some show and out comes a character’s phone, in zooms the camera, and they leave me to read the banal text-speak exposition. I leave the show instead. So I’m back on the home screen of Netflix. For some algorithmic, alchemic reason, one of its suggestions is Scent of a Woman, starring Al Pacino, from 1992. It’s Friday evening. Time is marching on. It’s gonna end up being too late if I waste another half hour waiting for Netflix to offer up something more intriguing. So I press play and watch the film for the second time.

Talking of phones, there’s a scene in which Chris O’Donnell’s character uses a clunky, early-model carphone that’s the size of a breeze block in the back of a limo.

More importantly there are some glorious set pieces: the tango scene, the Ferrari scene, the Thanksgiving scene. Pacino steals the show as a blind and bitter ex-Army colonel. The most famous scene is at the end of the film, when Pacino speaks up for O’Donnell in what passes for a kangaroo court in an American private school.

Pacino won an Oscar for a performance that some critics thought was over the top. Idiots.

I found this interview with the film’s director, Martin Brest, published only last November (2024). It covers every aspect of writing and making the film. It’s well worth the time if you can spare it. Pacino definitely did not phone this in. He trained at a school for the blind, and he deliberately unfocused his eyes during filming to achieve a performance that is uncannily convincing.

Pacino’s final speech in Scent of a Woman.

The last of the loosely joined dots in this post is a book called “How to Apologise for Killing a Cat,” by Guy Doza. It was a touching gift from someone I’ve had the pleasure to reconnect with in the last year. The book’s subtitle is “Rhetoric and the Art of Persuasion.” It gives names to the rhetorical tactics and figures of speech that we hear every day without consciously noticing them.

Pacino’s speech doesn’t quite use every rhetorical device in the book, but it uses a lot. For a start it’s five minutes of wall-to-wall pathos. And, at the very least, there are fine examples of Epiplexis, Epistrophe, and Apostrophe (trust me.)

Epiplexis. Epistrophe. Apostrophe. Now these are devices for telling stories. Much better than Razr, Pixel, or Galaxy.

Maybe try this too: Magicians and conspirators, how big ideas are conjured into existence.

Join the discussion:

-

Haha! Yes. Sorry for the scare.

-

Agreed. As the inimitable David Mamet says:

THE JOB OF THE DRAMATIST IS TO MAKE THE AUDIENCE WONDER WHAT HAPPENS NEXT. NOT TO EXPLAIN TO THEM WHAT JUST HAPPENED, OR TOSUGGEST TO THEM WHAT HAPPENS NEXT.

ANY DICKHEAD, AS ABOVE, CAN WRITE, “BUT, JIM, IF WE DON’T ASSASSINATE THE PRIME MINISTER IN THE NEXT SCENE, ALL EUROPE WILL BE ENGULFED IN FLAME”

We think about this in creative work. But we should also think about it when we brief creative work. Spoon feeding creatives keeps them on baby food.

in a similar vein, if we keep spoon feeding the viewer, they will only know how to digest baby food tv because they'll never have the opportunity and joy of thinking for themselves, processing subtle expressions and suggestions... all too often these annoying text messages we have to read aren't even necessary at all. five minutes later it becomes evident what was sent and read. at least if one is able to muster some basic deduction skills. but too many tv series makers treat the audience like bins to be fed. i used to call this type of entertainment american tv, but at some time in the past two decades, the US sneezed and the UK caught its cold. thankfully there are still many fabulous creatives at work, and generous people sharing it :)

Add a comment: