On Cults, Part 1

This week, Donald Trump led a rally in my city.

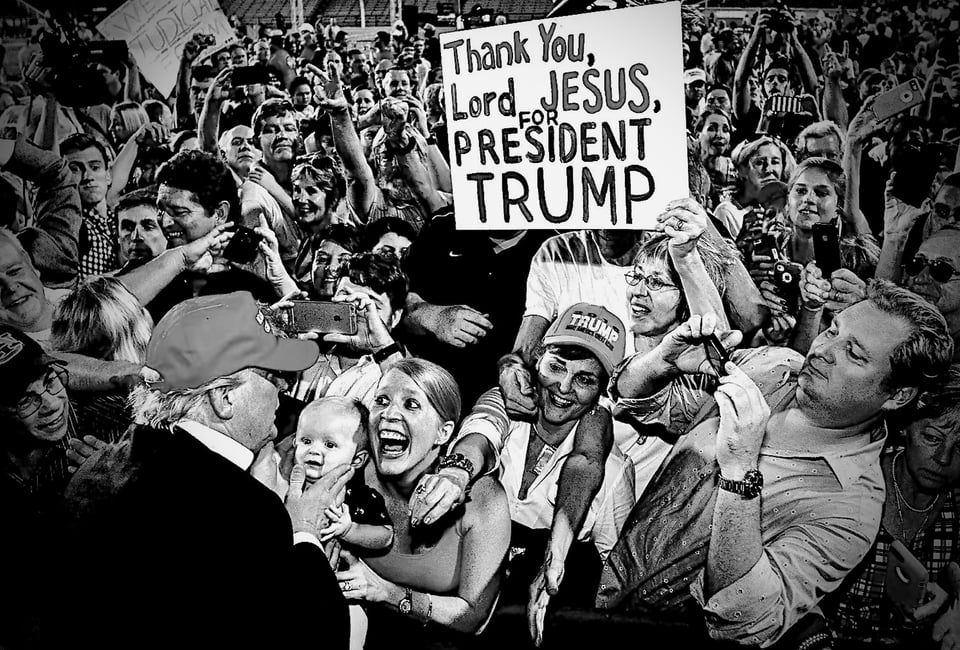

In the South Bronx, to be precise—it was a frenzied affair, the crowd reflecting a diversity that, if not entirely in tune with the majority-minority environs, certainly wasn’t the all-white, baying crowd typical of his rallies in other corners of the country. The freelance journalist Laura Jedeed, who attended the rally, described the pulsating mania and adoration in the crowd as something she knew intimately. “I've seen this reaction before,” she wrote. “The adulation, this fervor…it's a religious revival.”

Watching the slow, menacing roll of the polls toward November’s election, the unified zealotry of Trump’s true believers stands as a striking contrast to the listlessness and defeatism that characterizes a lot of his opponents. You can see that zeal all over—the book bans, the abortion bans, the sharp-voiced hysterics caterwauling at town meetings, the cranks gathering with guns outside librarians’ houses, the gold-haired charlatan at the helm of it all, dousing his welter of corruption in a promise of purges of the unwanted, the immigrants, the gays, the feminists. There’s a zeal in that promise that haunts me, a zeal in the acceptance of and longing for that promise that haunts me more. What you see in the eyes of a Trump-rally crowd is the fulfillment of dual desires: the desire to belong to something bigger than themselves, something vital, whose stakes are absolute; and the desire to believe in a collective redemption, delivered by a leader who, in many of their estimations, is a tool of God.

In Japan in the 1950s through the 1980s, a country convulsed by defeat in World War II and facing the end of emperor-worship and the displacement of millions of Japanese citizens from the countryside to urban environs reacted with an explosion of new religions. These ranged from Buddhist-inspired sects to sinister eschatological cults like the terrorist organization Aum Shinrikyo; from disciples of a flood of Christian missionaries to disaffected college students joining the Unification Church cult of Sun Myung-Moon. People were looking for a sense of belonging in a country whose history of isolation and tradition had been violently disrupted. They were looking for belonging and belief. That explosion has had moments of catastrophic fallout: the notorious Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system in 1995, killing fourteen and injuring thousands, with symptoms ranging from restricted breathing to temporary blindness. In 2022, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was assassinated by a man whose mother had donated all her family’s assets to the Unification Church, viewing Abe as a prominent sympathizer of the cult, with some justification. Instability, zealotry and violence roiled around this explosion in belief, this desire for belonging.

I’ve long believed that many of the fractious sects on the right qualify, in their own way, as new religions. The QAnon movement that has come to dominate the paranoid style in American thought is essentially a religious one; its signs and wonders are everywhere, and its guru is Trump. Other, weirder and smaller sects hang on the bandwagon: the “Blacks For Trump” initiative linked to the violent cult of Yahweh ben Yahweh; the relentless support of Falun Gong, the Chinese cult that funds the Epoch Times, a newspaper whose fawning coverage of Trump garners some thirty million pageviews a month.

Of course, the distinction between a “cult” and “religion” is open to debate—religious scholar and ex-Evangelical Chrissy Stroop argues that “cult” is an imprecise term used by fundamentalist Christians to marginalize other forms of belief while insulating themselves from scrutiny. But for the purpose of this examination, I’ll be utilizing a loose definition that incorporates ideological rigidity, conformity, control, and a demonization of the outside world. Having just written a book and a feature about religion, I can attest that it also emphatically includes the very fundamentalists that espouse that rhetorical divide.

Most prominently in the broader cult of Trump, the strain of Apocalypse-obsessed white evangelical Protestantism that began gaining strength in earnest in the 1970s, enveloping tens of millions of Americans in a vision of imminent blood and hellfire, has reached its apotheosis behind a leader whose flaws are permissible and even admirable in a moral landscape that has long focused its ire elsewhere—on the civil rights of women and minorities, on education, on the very specter of social change itself. Trump, protean and canny, has welcomed the mantle of savior to all these people; the sheer scope and meandering nature of his pronouncements make them amenable to parse for omens and portents. And his gaping, wounded ego makes him comfortable in the role of prophet-redeemer to his multifarious flock.

It’s uncomfortable to stand on the outside, watching the rush of adulation and belief swell into a tsunami poised to wash everything away. I live a life of fairly extreme isolation, and while my innate fear of crowds seems like solid insulation against the chanting multitudes, I’ve been thinking about vulnerability and belief a lot, lately. That’s why I started reading the memoirs of people who’d escaped cults—who’d lived lives of impossible rigidity, of abuse and deprivation, and who made it out. It’s a peculiar genre, a hyper-specific form of the bildungsroman that nonetheless has recognizable beats: describing the circumstances of entering the cult (by birth or choice), its depredations, the escape, the process of healing. I started reading them with the vague idea of understanding religion better, zealotry better, in a country that seems utterly consumed by the cruelest forms of both.

But then I kept reading. And reading.

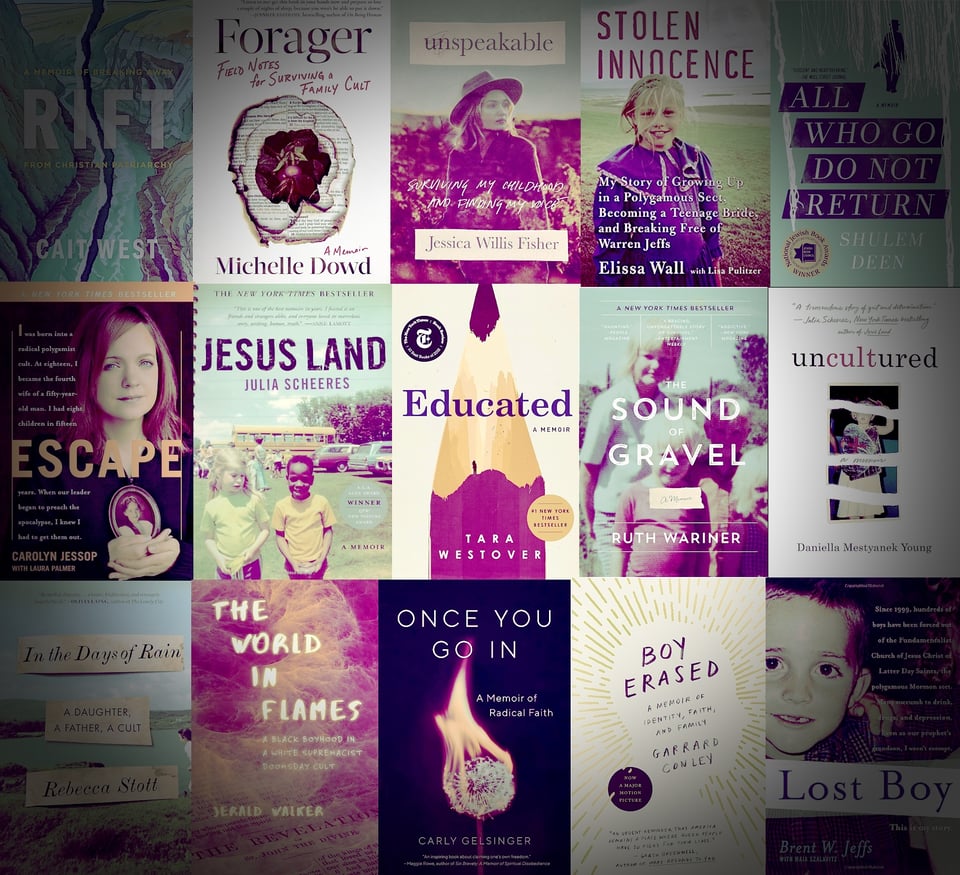

Here’s a tally of the ex-cult-member memoirs I’ve read since May 15th:

Rift: A Memoir of Breaking Away from Christian Patriarchy by Cait West (leaving fundamentalist Christian Patriarchy)

The Community: A Memoir by N. Jamiyla Chisholm (leaving a Black separatist Muslim cult in Brooklyn that divided families)

All Who Go Do Not Return: A Memoir by Shulem Deen (leaving Skverer Hasidism)

Jesus Land by Julia Scheeres (leaving an abusive fundamentalist home that sent her to a monstrous Christian “troubled teen” reform camp)

Educated by Tara Westover (bestseller about leaving an isolationist, survivalist Mormon family cult)

Uncultured by Daniella Mestyanek Young (leaving the Children of God cult, then entering and leaving the US Army)

The Sound of Gravel by Ruth Wariner (leaving a Mormon fundamentalist polygamist splinter sect in Colonia LeBaron, Mexico)

Forager: Field Notes for Surviving a Family Cult by Michelle Dowd (leaving an isolationist, survivalist fundamentalist Christian family cult)

Boy Erased by Garrard Conley (surviving “ex-gay” fundamentalist Christian conversion therapy)

Lost Boy by Brent Jeffs and Maia Szalavitz (an as-told-to account of a boy discarded by the Fundamentalist Latter Day Saints [FLDS] polygamist cult, whose uncle, Warren Jeffs, is a notorious pedophile and prophet)

Escape: A Memoir by Carolyn Jessop and Laura Palmer (FLDS, Jeffs cult)

Stolen Innocence by Elissa Wall (FLDS, Jeffs cult)

Unspeakable: Surviving My Childhood and Finding My Voice by Jessica Willis Fisher (leaving a fundamentalist Christian family cult of twelve children molested by their father, whose musical talents brought them to the America’s Got Talent quarterfinals and a TLC reality show)

In the Days of Rain: A Daughter, a Father, a Cult by Rebecca Stott (leaving the Exclusive Brethren, an England-based Protestant apocalyptic cult whose tactic of shunning infamously caused numerous suicides and murders in the mid twentieth century)

The Exvangelicals by Sarah McCammon (leaving an evangelical upbringing)

The World in Flames: A Black Boyhood in a White Supremacist Doomsday Cult by Jerald Walker (leaving the Worldwide Church of God)

Needless to say, the stories are crowded in my head, each with its own spin, its own tale of torment and purification and flight. There are commonalities in many: patriarchal control, abuse, educational deprivation, the perennial terror of an impending apocalypse, the denunciation of the world outside the cult as “worldly,” “Gentile,” “unclean,” dangerous, evil. Neglect, physical injuries, untimely deaths, a shunning of medicine and doctors. An insistence on obedience, often violently enforced. The subsuming of the individual into the collective, property emphatically included. Dress codes that distinguish cult members from outsiders. Twisted, labyrinthine, tormented family dynamics. The self viewed as worthless, impure, exchangeable, expendable—a tool at best, a liability at worst. Repetition as a method of enforcing belief. The self-splitting that occurs in trying to leave; the run-ups it takes, the years it takes to break down belief systems seeded over decades. What is left behind: family, certainty, love, identity. What faces the escapees: terrible uncertainty and fear and never knowing what’s “normal”; economic precarity. PTSD, panic attacks, trauma.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Subscribe now

These stories weave a tapestry about belief and the enforcement of its precepts that cross denominations, religions, sects; they are tales of domination and subjection and escape, of the triumph of the individual over the abusive collective. They are also stories of the abusive collective, and how it forms, and what it offers.

I’m still sorting out this curriculum (and reading more and more) and figuring out just what I want to say about it—and what these interlocutors have to say about where we are. Taken as a whole, they are a cautionary tale against the seductive nature of belief and belonging; they are a warning against flattening and further erasing the individuality and intellect of those who fall into these traps; they are tales of Houdini-esque escapes, feats of contortion of both mind and body in rebellion against privation. They are stories of how people who tell you what to believe, and couple it with physical and financial domination, can control you; they are stories about fear and obedience until the ground-down soul cracks open. They are remarkable. Painful. Sordid. Thoughtful. The prose ranges from crystalline and crackling to pedestrian and dull; the stories range from the thoroughly lurid to workaday horror and sorrow; there is so much courage here, and so much that never should have happened to require it.

This is (at least) a two-parter, and next week I’ll be diving into specific themes—misogyny, authority, obedience—that form the structure of a cult, and how they are reflected in our broader world.

Belief can be a solace and a prison. The need to belong and to believe—the need to turn to a stronger will, an authority whose self-confidence is so absolute it feels divine—is all around us. The voices of these apostates, a fractured chorus of survival, are stories about just how hard it is to escape the thrumming certainty of collectives, familial and societal, that reinforce belief, turn it into an unpierceable carapace against a threatening and fallen world. Taken together, they’re a story of cracking that shell open, and the price it takes to do so. Each leaves a family, a congregation, a community behind, of those who weren’t willing or able or equipped to break their minds and bones to get out—intentionally so, in communities that isolate and deprive for that very reason. These forces are emphatically present in our contemporary public sphere, in the limitless furor and zeal of Trumpian politics, and it behooves us to listen to those who have heard this tenor of belief before—and managed to shimmy through the tiniest of cracks to escape it.

-

Most prominently in the broader cult of Trump, the strain of Apocalypse-obsessed white evangelical

Protestantism that began gaining strength in earnest in the 1970s, enveloping tens of millions of Americans in a

vision of imminent blood and hellfire,

You're kind of describing a book I'm looking for, but haven't found yet. Can you recommend an account of the grassroots rise of both offsprings of Christianity that emerged in the 70's - the paranoid, apocalyptic vision you describe above and the Godspell/JC Superstar/Keith Green earthy brand I vaguely remember from elementary school? Did the former group splinter from the second or were they always on separate tracks?

Add a comment: