Notable Sandwiches #112: Marmalade

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, led gently by my brilliant and long-suffering editor David Swanson, meander down the path of Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, a British treat: the marmalade sandwich.

Autumn is finally more or less here, which in the US means hurricane season, a time of floods and trials, and everything turning orange. It’s also, for me, a time of surliness, when I turn to Gothic romances and bad moods, and in which I look to today’s generally pleasant task—writing about sandwiches—with undue hostility. Even poets are occasionally cranky about this time of year, as Robert Lowell was in 1961: “we have talked our extinction to death./I swim like a minnow/behind my studio window.” Or the reliably lugubrious Baudelaire’s Chant d’Automne: "Goodbye bright summer's brief too lively sport!… my heart's no more than a red, frozen block… the steady progress sounds like a goodbye." Which is why, despite an initial and quite heavy disinclination, writing about marmalade is actually rather a perfect tonic for this unfurling fug of the soul. (Another good antidote: this week The Best American Food and Travel Writing 2024 comes out and we're in it! And not just in it but praised in its introduction! By Padma Lakshmi! A ray of warmth to cut through even a most pernicious gloom.)

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

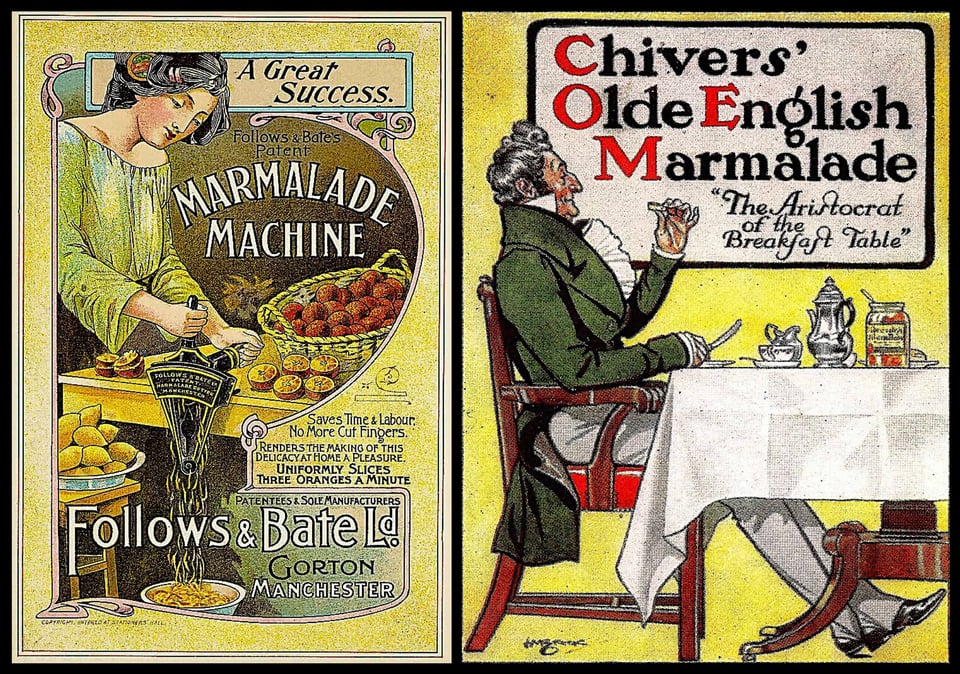

First, a few facts: marmalade is, technically, as the redoubtable food writer MFK Fisher puts it, “a skillful compromise between jellies and jams, and when at their best are six of one and half a dozen of the other.” In other words: a type of fruit preserve. The name probably derives from the original fruit used to create it, to wit, quinces—“marmalada” being the Portuguese word for preserved quinces, and first brought to Britain by enterprising Portuguese traders. Preserved quince paste is a very old dish indeed, dating back to the Roman Empire, where the venerable Apicius (much referenced in this series) provided a quince-and-honey recipe in his fourth-century opus De Re Coquinaria—an ancient marmalade.

Yet the term is almost universally used these days to refer to a bitter-orange preserve, and the origin of that transmutation, like so much else in culinary history, is somewhat difficult to fix upon. According to the exhaustive history The Book of Marmalade: Its Antecedents, Its History, and Its Role in the World Today, Together with a Collection of Recipes for Marmalades and Marmalade Cookery by C. Ann Wilson, the first English-language recipe for a Seville-orange marmalade appeared in 1714, in a cookbook by Mary Kettilby.

The fruit, while bitter, is very high in pectin, the thickening agent for jams and jellies, requiring no additional powdered pectin to set. According to that same source, the version the British adore today, with its “chips” of rind, originated in Scotland later in the eighteenth century. The marmalade sandwich, looked upon with adoration by the subjects of that empire, is quite simply what it sounds like: marmalade between slices of buttered bread. “Spread on buttery, crisp toast with its explosive cargo of sweet, sour and intensely bitter flavours, marmalade is a bedrock of our food culture,” wrote one journalist in The Independent in 1993.

There’s quite a bit of folderol about all this in British culture—Paddington Bear’s love of marmalade sandwiches, in particular, is a core character trait of this beloved British migrant. (I personally cannot watch any of the contemporary Paddington movies without wanting to crawl out of my skin, because the bear seems to have come from the darkest uncanny valley of Peru. It’s creepy and weird. In Paddington 2, though, our hero starts some sort of benevolent prison riot via mass production of marmalade sandwiches, which I sort of approve of.) Queen Elizabeth II really liked them as well. Apparently marmalade on toast is a reasonable alternative to the enormity of a “full English” fry-up for those who can’t face mushrooms and tomatoes and blood sausage upon arising.

Of course, none of this really resonates with my coarse American soul, for whom bitter-orange marmalade is nothing particularly special or nostalgic, although it is fairly tasty, and has a lovely autumnal color.

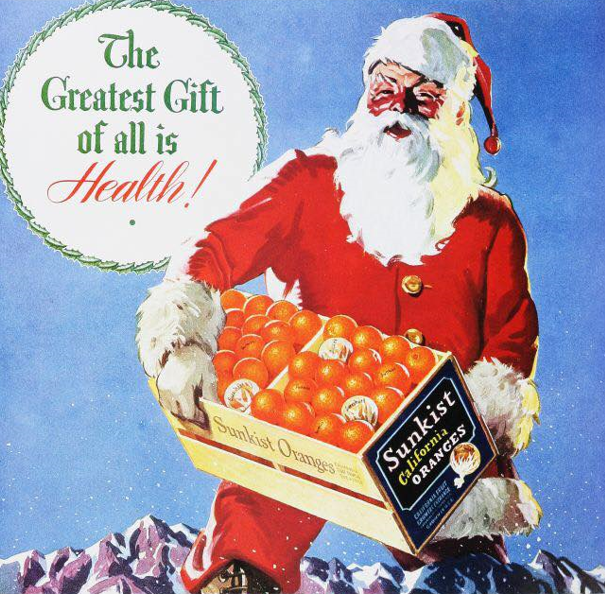

What gets to me are the oranges. Oranges have been part of European culture for a very long time, but for the vast majority of human history obtaining one while living in cold climes was something of a rarity (at least for those outside royal courts, whose jams, jellies and confitures were part of the general array of displayed wealth). Hence the Victorian-era tradition of putting an orange in a Christmas stocking—a more affordable imitation of St. Nicholas’ original gift, to poor maidens, of gold. Though it is a winter-ripening fruit—at its best between January and March—such was the orange’s scarcity, its bright rind and savor of Andalusian sun made it a gift of rare indulgence, particularly in the depths of winter.

The same tradition carried over to the Americas, particularly in the depths of the Great Depression, when the Florida Citrus Commission was founded and officially recognized by the state legislature in 1935. I’m not someone who finds hardship particularly romantic, either—but the idea of what is now a prosaic handfruit, a commonplace, being an object of such rarity and such delight is symbolic of a grand-scale transformation. We live now in a bountiful and perilous world—daily oranges and floods. The change is quite recent, too; my father recalls produce being far more seasonal in his childhood; the abundance of the contemporary supermarket’s produce aisle would dazzle any historical antecedent. The poet Robert Morgan, recounting his childhood in his 1984 poem “Oranges”, memorializes this view of the fruit as something special and incandescent:

Not once a year gold Christmas

things, as parents recalled, still

oranges were holiday and

maybe ten a winter lights, planets

stuffed bright as pencils in our socks.

Round royal orbs, each weighed a full

goblet. There was no other scent

to rhyme with this, no mix of resin,

flower. The meat and color were

a primary on which comparisons

were based. Daddy carved out a cone

so I could squeeze and drink.

The poets who make much of the melancholy of autumn have much to say about oranges, too, most of it transcendent with joy, although the Hebrew poet Dahlia Ravikovitch (1936-2005), a personal favorite, got really intense about them in her first book, The Love of an Orange, from 1959:

An orange did love

With life and limb

The man who ate it,

The man who flayed it.An orange did love

The man who ate it,

To its flayer it brought

Flesh for the teeth.An orange, consumed

By the man who ate it,

Invaded his skin

To the flesh beneath.

(The translation is by the miraculous Chana Bloch, one of the best literary translators I have ever encountered, with the benefit of more-or-less being able to read the originals; she is a marvel.)

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

That was a digression but I don’t regret it. It’s beautiful and strange, as an orange in autumn has been for most of human history. A marmalade’s quintessence is its preservation; that is why it has endured so long, because it keeps much of the ghost of the fruit alive in sugar and acid. It comes along with us into a time of seasonless fruit and will no doubt endure beyond it. I think this present reality—when every fresh fruit falls into our hands all year long, from California and Valencia and Thailand and Brazil even in the snow—must be temporary. For now an orange is an ordinary thing.

Still, if an orange must be prosaic, it can still be an object of joy.

So I’ll close this meandering column with a very good and very simple poem, about pleasure in ordinary things (and note sidewise how extraordinary it is that an orange should be a symbol of ordinariness, when for most of time it has been the opposite). Wendy Cope’s words here are a tonic and a delight. No wonder she received an Order of the British Empire for her poetry. I give her and her poem, “The Orange”, the final and joyous word.

At lunchtime I bought a huge orange—

The size of it made us all laugh.

I peeled it and shared it with Robert and Dave—

They got quarters and I had a half.And that orange, it made me so happy,

As ordinary things often doJust lately.

The shopping. A walk in the park.

This is peace and contentment. It’s new.The rest of the day was quite easy.

I did all the jobs on my list

And enjoyed them and had some time over.

I love you. I’m glad I exist.

-

Oh, this was absolutely delightful. Just what I needed to read on a grey day, and I'm going to check out more of that poetry, so thank you for that.

Also, Ikea's elderberry & orange marmalade is very good for those of us who find straight orange marmalade a little too cloying (quince jam or marmalade is wonderful, too, but hard to find in the US). Reading about quinces is a total rabbit hole, prompted by listening to a tree podcast on quince (Completely Arbortrary, for fellow nature lovers).

-

I feel like quince should be the plural of quince now.... yeah, showing my boomerness with the ellipses. I embrace them.

-

Born and raised in the UK, I'm a huge fan of marmalade! For most of my (62-year) life I've always loved Rose's Lime Marmalade, but orange marmalade is a lot easier to find. Dark, thick cut is my favorite -- "Olde English" style -- but almost any marmalade will do in a pinch. For me, the preferred vehicle is crunchy, well-buttered toast -- but I won't turn down untoasted bread if it is slathered with marmalade!

-

Just finished the Southern hemisphere season of Seville oranges in Australia where making marmalade is a required accomplishment of every farm cook. They also make a wonderfully bittersweet candied peel, which can be coated in dark chocolate or rolled in sugar for use in baking. I can report from recent experience children do not like chocolate-covered peel.

Add a comment: