Meaning making through the lenses of the Free Energy Principle

How the Free Energy Principle reveals meaning-making as the biological process of finding coherence and how our entire experiential reality—from basic perception to higher cognition—is a necessary fabrication.

The Free Energy Principle (FEP) proposes a unifying theory of how living systems persist. Life exists in direct opposition to entropy. While the universe trends toward disorder, living things resist it. A plant keeps its leaves green, a bird maintains its body temperature, a cell preserves its boundary.

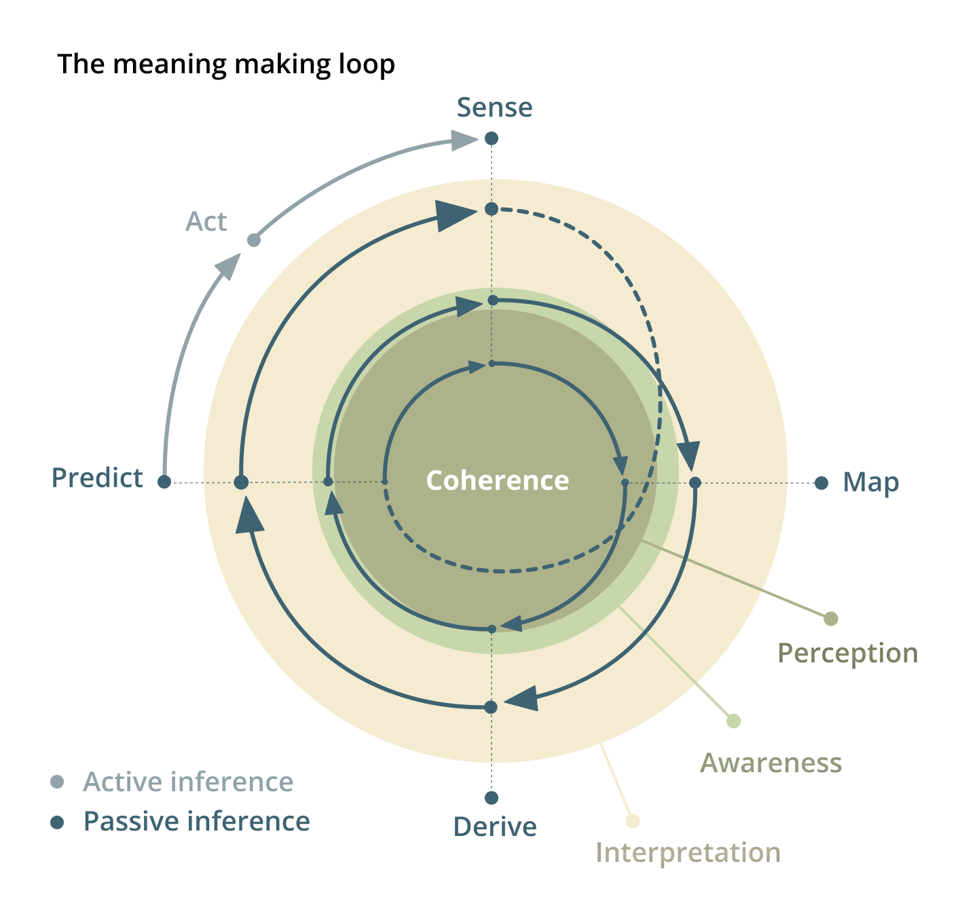

The FEP explains how this is possible: living systems must minimize the difference between their expectations and their sensory experiences. This difference represents uncertainty about the world. It's called "free energy" in analogy to "thermodynamic free energy" which measures potential for change. Too much uncertainty threatens survival, so living systems evolved two strategies to minimize it:

- Passive inference: updating internal models to better predict reality

- Active inference: changing the environment to match predictions

From perception to higher order cognition, the FEP describes how living beings make sense of reality to stay alive.

The FEP is fundamentally a mathematical framework. This is my attempt to present it through the phenomenological lenses of meaning. Free energy minimization is in essence the process of finding coherence.

While in previous articles I focused on the general ideas of seeking meaning and understanding, what I explain here is the specific mechanism.

Meaning making as Passive Inference

Imagine opening your fridge and finding a pink elephant. You can't simply continue your day. Your mind demands coherence. There's cognitive dissonance because your models say this shouldn't happen. You must find an explanation - perhaps you're dreaming, wearing a VR headset or it is a realistic toy. Your brain will keep trying interpretations until it finds one that restores coherence.

To make sense of reality, our brain must update its models to match what it senses. This is meaning making, and it is passive inference - they are one and the same.

Our brain constantly updates its models through a continuous loop. We sense something, map it to a model that could explain it, derive its inherent qualities, and use these qualities to predict what we should sense next.

- Sense: Sensory input is gathered, but it's already interpreted by the predictions from previous loops. What am I seeing is already influenced by what I expected to see.

- Map: Selects an internal model that resolves the incoherences identified in the prior cycle. It looks for a model where previous predictions and current senses align.

- Derive: By using this new model, it gains access to all its inherent qualities. It extrapolates new properties and behaviors.

- Predict: Anticipates what should be sensed next if the model is accurate. This prediction influences and constrains what will be sensed.

Inference from perception to interpretation

Walking through a forest, you experience trees as solid, living things. This experience emerges through layers of meaning making, from basic perception to conscious thought.

In low level layers, wavelengths become colors and vibrations transform into sounds. In following layers percepts are created combining them into objects with volume and distinct sounds. This is perception. It transforms raw input by inferring from low level models to fill up sensory gaps and create more complex objects. The light patterns become tree-like shapes.

Because perception is an unconscious process, we remain unaware of the layers of inference involved. We don't experience wavelengths becoming colors or shapes merging into objects. Instead, we only perceive the final result, often described as "awareness."

Interpretation arises as this loop continues to spiral outward, scaling to higher levels of abstraction. When the perceptual model is recognized as a tree, it acquires mass, behavior, and purpose. Interpretation involves integrating these features into broader contexts and narratives by assigning meaning.

"To give meaning" is to infer beyond what is there. When you look at a tree your sensory receptors only receive electromagnetic wavelengths and vibrations. Everything else is inferred from models. When sensory input matches a known model, it inherits all its qualities. Something that looks and acts like what we've seen before will likely behave the same way. This is inference.

We read emotions in subtle muscle movements, intentions in silence, significance in coincidences. We see faces in clouds, patterns in chaos, and purpose in life. Inference shapes every aspect of our experience.

Context conditions what is sensed

As the meaning making loop spirals outward, each model must fit into increasingly encompassing ones, creating a hierarchy of meaning. These higher-level models influence each new cycle by feeding context to the following predictions.

A pattern of colors can be interpreted as bark texture because it fits within the context of a tree, which itself fits within a natural environment.

Higher level models create requirements for coherence. When there is incoherence, the next cycle must either find new models to map what is sensed, or change the environment to restore coherence.

The broader context constrains what interpretations are available to us. Ambiguous patterns are more likely to be interpreted in ways that maintain coherence with the context. What we can perceive is constrained by what makes sense within our current understanding. When walking through a forest, unclear shapes are more readily interpreted as branches or leaves. The same visual input might be interpreted differently in an urban setting. Sensing doesn't start from nothing - it begins already shaped by the predictions of higher level models.

When predictions don't match our input, we act to resolve the incoherence. We shift attention to unclear features or move closer to verify textures. This is active inference: act upon the environment to align sensory data with expectations.

When the loop breaks down

The highest level models must find coherence for our entire existence, they function as an all-encompassing model of the current reality. They shape our fundamental understanding of who we are and what purpose we serve responding to questions like "What am I?" and "What is the meaning of life?".

When coherence cannot be restored at this level, depression emerges. This breakdown of meaning making stems from the belief that coherence is impossible to achieve. The loops of active inference and interpretation collapse. Without belief in the possibility of making sense, there's no drive to act or understand. The brain stops engaging with reality, leading to paralysis and loss of motivation.

Meaning making is discrete

When you look at the duck-rabbit illusion, you see either a duck or a rabbit. Never a duck-rabbit hybrid, never something in between. Your brain commits fully to one complete interpretation. The same sensory input produces entirely different experiences with different qualities and expectations.

When you look at the duck-rabbit illusion, you see either a duck or a rabbit. Never a duck-rabbit hybrid, never something in between. Your brain commits fully to one complete interpretation. The same sensory input produces entirely different experiences with different qualities and expectations.

This discreteness appears everywhere. A pattern of light might be a tree or a person in the dark. A pink elephant could be a hallucination, or a toy. An unexpected silence becomes thoughtful reflection, hidden anger, or simple distraction. Even with language, when we hear fragments of conversation or read ambiguous poetry, our brain constructs complete, discrete interpretations.

We can't maintain multiple simultaneous meanings. Our conscious mind might acknowledge ambiguity, but our immediate experience must commit to one coherent interpretation. There is no middle ground, no blend between alternatives.

This commitment to discrete interpretations is fundamental and necessary. Each interpretation is read through an entire web of interconnected models that must remain consistent - you can't see something with a tree appearance that moves like a walking human. When high-level models change, this cascade forces all dependent models to restructure. Interpreting an experience as a dream changes everything from how we perceive physical laws, to how we relate to people present, to what we expect might happen next. The more comprehensive the model, the larger the web of sub-models that needs to remap to maintain coherence.

The phenomenological experience is fabrication

Our experiential reality is the direct fabrication of meaning making.

Only a fraction of physical reality enters our experience. Reality doesn't exist as experience until we engage our senses. And what we do capture is transformed way before it reaches our consciousness. Sensations are already interpretations, constrained by our broader contextual understanding.

But just like understanding is not possible without a model, without diversity of models we are trapped in single interpretations. If you've never seen a rabbit, you can only see a duck. Yet, we know physical reality is not one interpretation or another, nor anything in between.

Two people facing the same situation will map it to completely different models, experiencing fundamentally different interpretations. While over time, through continuous iterations of the meaning making loop these interpretations may converge, they remain fundamentally constrained by their models.

Fight for truth is fight for coherence

Despite this evidence, it's hard to grasp how far our experience is from physical reality. We only know our phenomenological experience and by necessity it strives towards coherence. This coherence makes it feel like truth. The danger lies in forgetting it's constructed. When we forget the fabricated nature of our experience, we become blind to how truth might not be as straightforward as we take it to be.

This blindness manifests most dramatically in our highest-level models. Spiritual, scientific, and personal narratives all compete to provide an all-encompassing model through which everything must make sense. In their fight for total coherence, they create fundamental incoherence, generating suffering as we struggle to make everything fit.

These issues stem from a deeper problem: the pursuit of absolute truth itself. We fight to defend our interpretations as "true," either against others or within ourselves. But this fight for truth is really a fight for predictability. We can only understand others when we share models. Imposing truth is just another way to restore coherence through shared understanding.

Beyond fabrication

The Free Energy Principle reveals meaning making as a fundamental process of living systems - the mechanism through which we maintain accurate predictions. Each layer of experience emerges from the need to minimize uncertainty and find coherence. This exposes both why we fabricate meaning and how deeply constructed our experience is.

We can't escape fabricated reality entirely - perception itself is fabrication. Yet we can reduce layers of interpretation. This state of minimal interpretation, often called "non-dual" or "pure" awareness, acknowledges the fabricated nature of experience while remaining as close as possible to direct perception.

Different traditions provide guidance toward this possibility. Advaita Vedanta through self-inquiry, Buddhist traditions through meditative practices of simple observation, and psychedelics through dissolution of conceptual boundaries.

Our phenomenological experience is the most real thing we know, yet it remains an interpretation - different from physical reality and unique to each person. By recognizing this, we step back from the need for total coherence. Without mapping experience to broad narratives, we can experience reality simply "as it is" - a state that many spiritual traditions have pointed to. While we can't escape fabrication entirely, we can find peace by holding our models as what they are: tools for prediction, not representations of ultimate reality.

You just read issue #3 of The Meaning Gap. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.