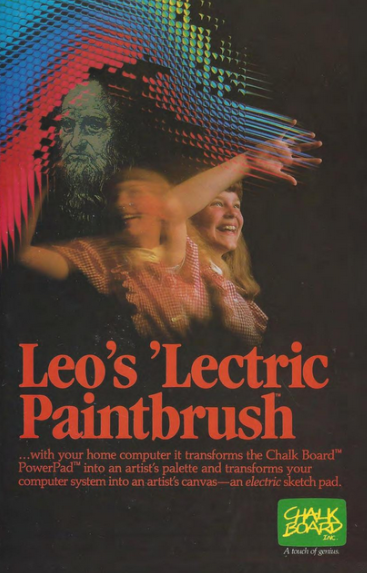

Bad ad, but almost an iPad (in 1984)

I, for one, am glad that one of the greatest paintings of all time wasn't an 8-bit image drawn by this guy.

This newsletter does not contain ads, sponsored posts, or affiliate links. Open and click tracking are disabled. And there is no paid upgrade or AI generated content. Enjoy!

Ah yes, if only DaVinci had painted the Mona Lisa with digital finger paint. If only he had been blessed with a chunky beige slab boasting 14,400 switches crammed into a 12”x12” prison of lost potential. If only.

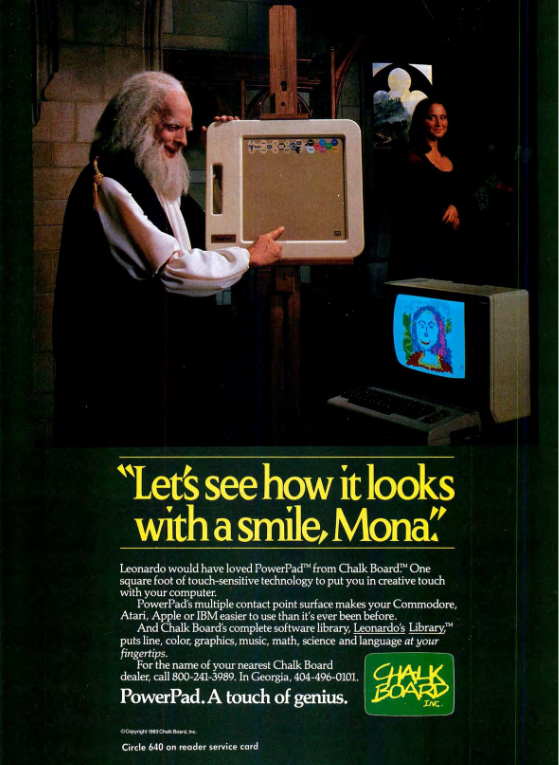

This 1984 full-page ad for Chalk Board Inc.’s PowerPad is such a superb representation of tech advertising in the 80s and 90s. It is hilarious, outlandish, and baffling.

Why is pervy Leonardo standing to the side of and behind the easel?

Why did he choose Cerulean Regret for Mona Lisa’s pixelated face?

Why, for the love of the Omnissiah, did anyone on set that day think he should be tracing her cleavage with his pointer finger and a giggity smile on his face??

Good lord I hope that model got paid in kind for a face that so perfectly conveys the absurdity of everything in that photo.

The wildest thing about this ad, and many of the others I’ve been hoarding [subscribe to see more!], is that the hardware and software on display was actually pretty cool.

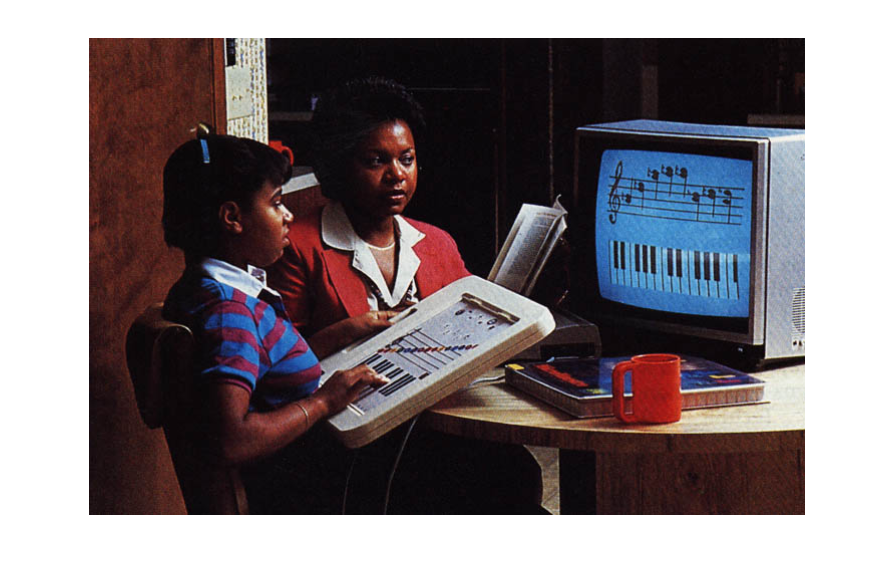

The PowerPad™ was a 4.5lb hunk of plastic (“portable enough for a child to carry around” according to a 1983 Creative Computing article) with a touch-sensitive surface. Despite a name suspiciously similar to Nintendo’s Power Pad, released a few years later, they don’t seem to have much of anything in common?

Chalk Board Inc.’s “input device” could translate multiple, simultaneous points of contact into inputs for Commodore 64s, VIC20s, Ataris, Apple IIs, and IBM personal computers (“basically anything with a 6502, a processor I've always been fond of” according to the lead software developer; more on him later).

DaVinci is using a Commodore64 or VIC-20 in the ad, for what it’s worth, which means his canvas would have been wired via Control Port 1 (Ataris used the game left controller port, Apple IIs used the i/o game port, and IBMs used the printer port).

“You are in charge. No longer are you at the mercy of traditional computer ‘buzz words’ and entry techniques,” the User’s Guide read. At least, until PowerPad released a Programming Kit that let you code your own “command buttons” (via XY coordinates) and subroutines.

To be fair, other than the dev kit, the programs that made it to market (before the company went under) seemed to have actually delivered Chalk Board’s promise to simplify computer inputs!

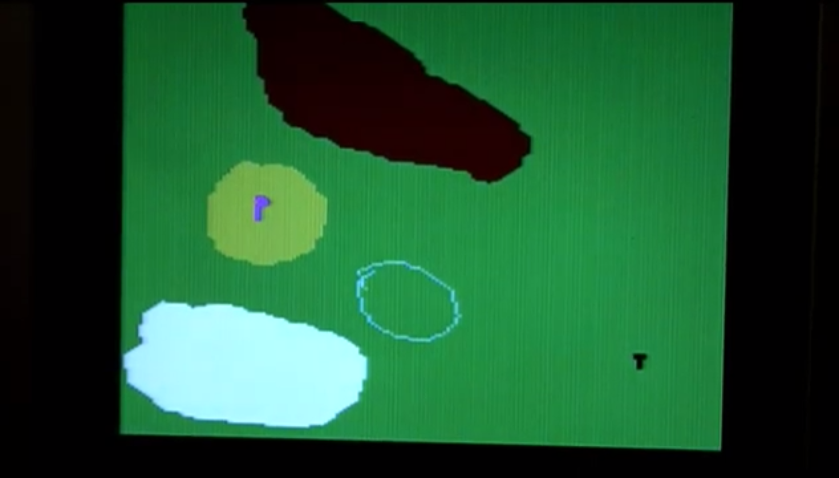

Would you believe that in 1983 a PowerPad game would let you draw your own golf course (with sand traps and water features!) using your finger or a stylus and then immediately play that course?

Or that you could press three piano keys at the same time to record and play polyphonic chords. Chords that you could string together and save to replay later? Ten whole years before the Newton? C’mon!

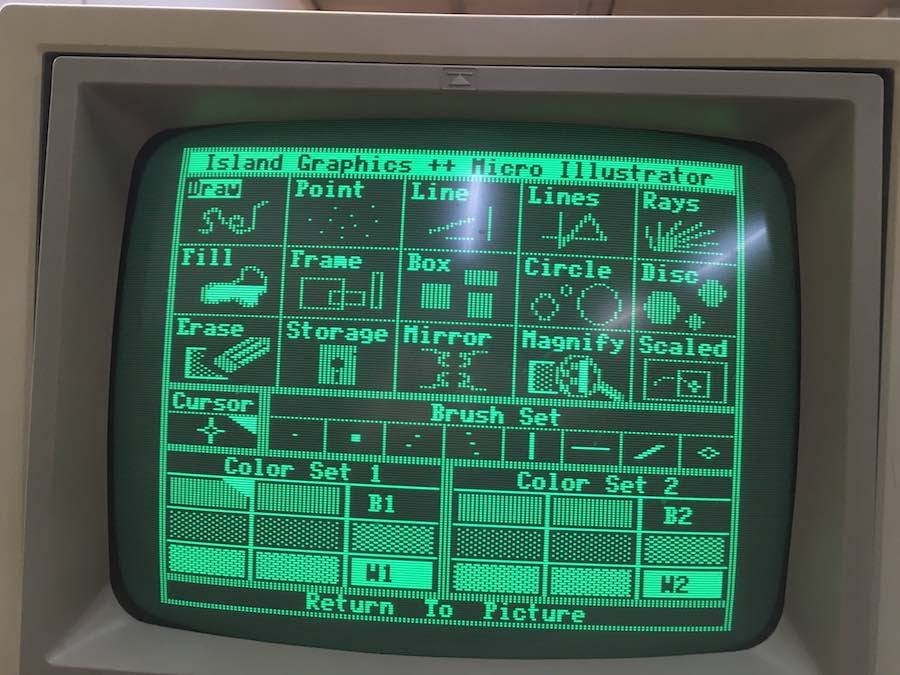

Micro Illustrator seems like it was actually PowerPad’s most capable drawing program, based on its software guide, but DaVinci the narcissist hogged all of the marketing dollars with his own art software:

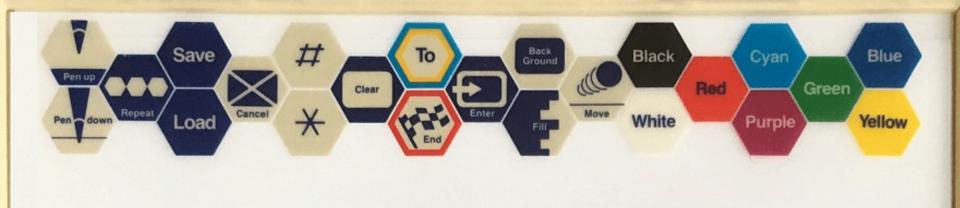

Every PowerPad cartridge or diskette came with a mylar overlay, oddly reminiscent of Macbook’s app-specific Touchbars that would come 40 years later.

The hexagons you see in the Mona Lisa ad are the overlay from Leo’s ‘Lectric Paintbrush, which had 15 function buttons and eight color selectors. Most were self-explanatory while some veered dangerously close to the “traditional computer ‘buzz words’ and entry techniques” that the User’s Guide derided.

The ’Lectric Paintbrush documentation claims, for example, that after pressing the “hashmark” overlay “A vertical memory gauge appears. It sits to the right of the screen's picture. It doesn't interfere with your drawing. As you use memory, the gauge fills with ink.”

If Leonardo wanted to save his obviously superior version of the Mona Lisa to his “diskette based system, the diskette on which you save pictures must contain Atari DOS.” Others were saving their creations on…film? To whit the ‘Lectric Paintbrush guide recommends:

Use a 35mm camera. An Instamatic-type camera will not work. Mount the camera on a tripod. Attach a cable release.

Darken the room to avoid reflections on the screen. If you prefer, tape the open end of a blackened cardboard box flush to the screen. In the closed end of the box, cut a hole slightly larger than the size of your lens. Proper screen and room lighting are found best through trial and error. All televisions and monitors differ. Do not use a flash.

Use f(stop) 8 at ¼ of a second shutter speed with ASA 64 Daylight film. Never use a shutter speed shorter than 1/15 of a second.

Take meter readings and record them.

Bracket your exposures; expose one full stop brighter and darker than your original setting.

Keep records of your exposures for later reference.

[NOTE: Next issue will dive into a magical ad for a device built specifically to capture computer screenshots on film, also from 1983.]

Replacement overlays for PowerPad software were available for six dollars, “$3.00 for the replacement overlay itself, and $3.00 for postage and handling,” which screams value.

Ken Thompson was the lead software developer for PowerPad’s graphics subsystems (not to be confused with the Ken Thompson who worked at Bell Labs, implemented Unix, and invented the C language). The Ken who worked for Chalk Board Inc. described it as a “true startup” that was, apparently, targeting pre-K children, which makes the Mona Lisa ad so much worse!

The PowerPad literally had a program where a panda would giggle when you pressed its belly button. But no! Let’s show ‘em Leonardo DaVinci in a dingy, dimly lit basement asking a pretty woman to smile more. That’ll get kindergarten teachers interested.

Ken also wrote of his time working on the PowerPad: “This was my first ‘real’ job and being young and naive I was pulled to the notion that we were at the cutting edge of something, we'd be the next Apple and all get rich. We weren't. We didn't. I was the first software developer hired, the last let go and that spanned a year almost to the day. I left that job wiser, more mature and with the one thing upon which all my future happiness depended.”

Maybe it was creepy DaVinci that eventually did Chalk Board Inc. in. Or the 20% off rebates in game magazines. Who knows.

The hardware retailed for $99.95 (I found a few collectors who seem to be selling them today for anywhere from $70 on eBay to $350 at a Denver-based vintage shop). That’s bittersweet, if you ask me. Sweet that a startup from the 80s that couldn’t survive a year released a product that we can still learn this much about 40+ years later. Bitter that the PowerPad never got more of a chance. It had good ideas!

“Its power is such that children and adults alike will soon be found curled up on couches throughout the land entranced by its spell,” Joe Devlin wrote in a 1983 review. “Its utility is such that many programs are being written to make use of the magic it wields. The magic of Power Pad is that it is a tabula rasa.”

I write about tech history a lot. But that was not the reason I started this newsletter, honestly.

I just kept stumbling across wild and impossible-to-ignore ads and thinking that other people might enjoy them as much as I do; might feel a little better about today’s AI slop, advertising-everywhere hellscape.

My original plan for each issue was to be ~300 words of dunking on outdated marketing with some light historical anecdotes. But my god the rabbit hole I fell down on this one. And I didn’t even include everything from my research that I found fascinating!

If you want more ads and less history, or vice versa, email me and let me know. Because at this point I could fill a book with either, as long as I have others to savor it with me.

And, if you’re interested, here is most of my research for anyone who wants to learn even more about the PowerPad: