The pace of publishing quickened this week. I’ve done some things to the site to make it easier for me to post; at some point I’ll write that all up in a really boring meta way that only a few people will care about. In the meantime here’s what I'm currently...

Reading: How Life Works: A User’s Guide to the New Biology, by Philip Ball (I hated biology as a kid, but this book is really well done and super interesting)

Listening: Pearl Jam by Pearl Jam (I may be regressing?), and Two Star & The Dream Police by Mk.gee (recommended by munchkin #1, who is definitely no longer a munchkin).

Watching: The U.S. Open. (Jessica Pegula!!!)

...and below is what happened on the blog this week. Words! Links! Stuff! I hope you enjoy.

I recently finished and highly recommend Biography of X, by Catherine Lacey. It’s a fictional biography of a multi-hyphenate downtown New York artist from the 70s. It’s an alternate history of the United States. It’s a meditation on identity. It’s an investigation of what it means to make art. And it’s an obsessive love story, written by a widow who’s blinded by anger and grief.

Audrey Wollen’s excellent review in The New Yorker will give you a taste of what you’re in for.

Lucca’s biography begins with a wail of grief, and a repudiation of history. Lucca, the narrator and a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, is mourning the death of her wife, X, a maverick star of the art world, who built such a baroque structure of mystery around herself that even Lucca struggles to identify whom she has lost, whom her widowhood honors. X has done everything, been everyone: a conceptual artist à la Sophie Calle, a lyricist and producer on David Bowie’s “Low,” a stripper in Times Square alongside Kathy Acker, an interlocutor with the feminist Carla Lonzi, a fiction writer who inspired Denis Johnson, a terrorist on the run, even a secret F.B.I. agent. Familiar uncertainties – Who was this person whom I loved? Did I ever know her? Is it possible to love what one cannot know? – turn into a far-reaching, propulsive detective story that spans the last half of the twentieth century.

The question driving Lucca’s investigation appears, at first, to be a simple one: What was her wife’s name?

Four passages I highlighted, just to give you a taste:

Page 33:

But I know now a person always exceeds and resists the limits of a story about them, and no matter how widely we set the boundaries, their subjectivity spills over, drips at the edges, then rushes out completely. People are, it seems, too complicated to sit still inside a narrative, but that hasn’t stopped anyone from trying, desperately trying, to compact a life into pages.

Page 140:

“Is life in the small things, in songs or stories, or is in the large things, in the country, its laws, in the liberty and safety of others?”

Page 175:

You are not your name, you are not what you have done, you are not what people see, you are not what you see or what you have seen. On some level you must know this already or have suspected it all along — but what, if anything, can be done about it? How do you escape the confinement of being a person who allows the past to control you when the past itself is nonexistent?

And finally, page 269 – one small example of the world building Lacey does throughout the novel:

Though it is difficult to imagine now, the occupation of “artist” in America was seen, prior to World War II, almost exclusively as a male calling; it was only through the intersection of a variety of economic and cultural events that this stereotype was inverted and women were seen as the sex to whom “art” belonged. (Why it had to belong to one sex or another is another matter entirely.) Many have identified the Painters’ Massacre of 1943 as a crucial turning point in this reversal. In December of that year, a mob of Southern separatists stormed an opening at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York, killing fourteen male artists – Marchel Duchamp, Alexander Calder, Wassily Kandinsky, and Jackson Pollock among them – while sparing all the women. This act of terrorism might have been more well-known if it hadn’t been one of the less-deadly incidents perpetrated by similar groups; as it stands, it appears more often in art history books than in books on the Great Disunion.

So good. Go read it.

Alexis Madrigal on a mulberry leaf growing in his backyard.

In the shade, the leaf is solid and waxy, reflective—the blue sky right now is laying on its the ridges. The texture is so singular, so perfect that it reveals a new dimension of failure for our digital cameras. The lustrous sheen is inseparable from this particular green, and it cannot be captured. The leaf is not iridescent like an abalone shell; it doesn’t reveal rainbows through optics. But it should be in that same magical category! This is a green that reveals the whole spectrum of green and suggests that it might run beyond our perception. This is beauty. My eyes find the leaf from all the angles of our yard.

Emphasis mine.

Two widely-linked things are bouncing around in my head, and I think they’re saying the same thing. First, Ted Chiang on Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art, emphasis mine:

The companies promoting generative-A.I. programs claim that they will unleash creativity. In essence, they are saying that art can be all inspiration and no perspiration—but these things cannot be easily separated. I’m not saying that art has to involve tedium. What I’m saying is that art requires making choices at every scale; the countless small-scale choices made during implementation are just as important to the final product as the few large-scale choices made during the conception. It is a mistake to equate “large-scale” with “important” when it comes to the choices made when creating art; the interrelationship between the large scale and the small scale is where the artistry lies.

And second, Paul Graham on Founder Mode:

There are as far as I know no books specifically about founder mode. Business schools don’t know it exists. All we have so far are the experiments of individual founders who’ve been figuring it out for themselves. But now that we know what we’re looking for, we can search for it. I hope in a few years founder mode will be as well understood as manager mode. We can already guess at some of the ways it will differ.

Graham argues that “there are things founders can do that managers can’t.” While there literally may not be tasks that a founder can do that a hired manager can’t, there are certainly decisions a founder can make that managers can’t. Because they lack the context, the experience and the history that a founder has. To bastardize Chiang for a minute, founder mode requires making choices at every scale; it’s the interrelationship between the large scale (strategy) and the small scale (the design of a listing page) where founder mode lies.

Sam Kahn on the…I hate myself a little bit for using this word…vibe of every decade from the 1880s to the 2020s:

1920s — Pure hedonism. Hedonism tinged with grief, hedonism as the fruit of experience. The sense of being passed over by technology. José Capablanca seeing a film of himself at the peak of his life and weeping uncontrollably that he would never be that again. Benjamin Button’s misfortune of growing ever stronger and younger, only to sink again into senescence.

And:

1980s — Cocaine. Phil Collins’ psycho solo. Patrick Bateman catching up to a woman on the street at night. Seducing her with a glance at his suit. Cut to the next day, trying to have his bloody sheets cleaned at the dry cleaner’s.

Notion has hit 100M users and there’s much to love in the email that Ivan Zhao, the founder, sent to celebrate the milestone.

In our early years, we were rather lost. … We had no business sense, struggled with building a horizontal tool. Notion almost died. (Thanks for the bridge, mom!)

And…

Notion is built on the 70s’ vision that software can “augment human intellect”. … The world needs a “LEGOs for software” and Notion is here to build that! With our LEGOs, a community of non-programmers can sell “software” built on Notion (some made $1M in 2023!) We dreamed of this in the original pitch deck, but I wasn’t sure it would come true. It’s gradually coming together, though instead of 15 months like we imagined in our original pitch deck, it took us 10 years 😅

And…

As with our mission, our love for craft hasn’t changed. We tried 30 shades of warm white paints for our office wall. We couldn’t find merch we love, so we made our own work jackets. We care about craft & beauty, and we want to bring them to this world.

What I love about Notion is that is both highly opinionated and internally consistent. Once you understand how Notion works, how those LEGOs fit together, the light bulb goes off about (a) what you can do with the tool, and (b) where your contraints are. (You can do a lot with LEGOs, but not everything.) I think Notion is one of the more interesting products to come out of “the Valley” in the last decade, and Ivan’s email was a nice peek into the culture driving the company. More like this, please.

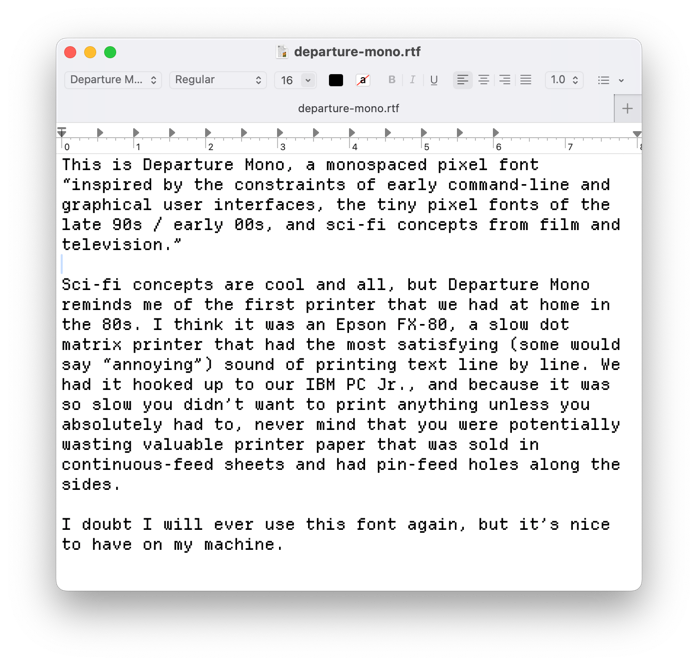

Via Daring Fireball, Departure Mono.

Nim Daghlian summarizes what they took away from XOXO (again, driving my RAHMO). I particularly appreciated this particular bit from Darius Kazemi about the definition of “indie.”

Darius Kazemi says “Indie is just an economic descriptor” in his funny, insightful talk about the highs and lows of trying to make it building independent projects and communities on the internet, in part as a followup to his 2014 talk “How I Won The Lottery” This was to say that it’s a way of existing in the market, rather than a coherent aesthetic or a value system, and it can be liberating or fuck you up in equal measures.

And I also liked this:

I feel like all these conversations and calls to action I hear have this in common; they’re calling for an active and critical engagement with the internet – what we put on it, how we build it, and how we use it to connect with other people. For some people that means writing your own CMS from scratch and federating all your posts to multiple services. For others it might mean making a mutual aid Facebook group. Or maybe just starting a text thread with friends.

Both of these snippets are refreshing in their “different strokes for different folks” vibes. Because there is no one right way to internet.

Highly recommended: the latest episode of The Ezra Klein Show with Jia Tolentino (author of Trick Mirror, a book I’ve probably recommended more often than any other in the last few years) about parenting, pleasure, psychedelics, reading, attention, smart phones and Cocomelon. This exchange hit home, emphasis mine…

jia tolentino: And it sometimes feels to me not that we’re turning away from the mess and the wonder of real physical experience, despite the fact that it’s precious. I kind of feel something within me sometimes that it’s too precious. It’s too much, that being present is work, in a way, that it’s this rawness, and it’s this mutability. It requires this of us and a presence. That is something that I have sometimes found myself flexing away from because of all the reasons that it’s good, in a weird way. Have you ever — do you know what I mean at all?

ezra klein: I absolutely know what you mean in a million different ways. I mean, I was a kid. Why do I read? I mean, now I think it’s almost a leftover habit, but I read to escape. I read to escape my world. I read to escape my family. I read to escape things I didn’t understand. And I read obsessively, constantly, all the time, in cars, in the bathroom, anywhere.

tolentino: Totally.

klein: Because it was a socially sanctioned way to be alone.

tolentino: Right.

klein: And nobody would bother me because it was virtuous for me to be reading.

Via @ranjit, shonkywonkydonky’s complete Radiohead cover album, OK Computer but everything in my voice. “Airbag” broke my brain, but by “Exit Music (For a Film)” I was hooked.

Kieran Healy from 2019, Rituals of Childhood.

The United States has institutionalized the mass shooting in a way that [sociologist Émile] Durkheim would immediately recognize. As I discovered to my shock when my own children started school in North Carolina some years ago, preparation for a shooting is a part of our children’s lives as soon as they enter kindergarten. The ritual of a Killing Day is known to all adults. It is taught to children first in outline only, and then gradually in more detail as they get older. The lockdown drill is its Mass. The language of “Active shooters”, “Safe corners”, and “Shelter in place” is its liturgy. “Run, Hide, Fight” is its creed. Security consultants and credential-dispensing experts are its clergy. My son and daughter have been institutionally readied to be shot dead as surely as I, at their age, was readied by my school to receive my first communion. They practice their movements. They are taught how to hold themselves; who to defer to; what to say to their parents; how to hold their hands. The only real difference is that there is a lottery for participation. Most will only prepare. But each week, a chosen few will fully consummate the process, and be killed.

George Saunders on getting the water to boil in a story:

We might, for simplicity, think about those first five minutes of a movie, and in particular, that first incident that tells you what the film is “about,” or “what you should be wondering.” For me, it’s a bit of an “aha” feeling, kind of like, “Ah, I see. Oh, this could be good.”

Elsewhere I’ve described this as the moment when the path of the story narrows.

One way of thinking of it, in terms of the famous Freytag Triangle: the water starts boiling when the story passes from the “exposition” phase, into the “rising action” phase.

A story made up of all non-boiling water is perennially stuck in the “exposition phase.” We might think of this as a section where the components are joined by a series of “and also” statements. “The house looked like this and also the yard looked like this and also the family was made of five members (and also, and also).”

(At this point, the reader may ask the Seussian question: “Why are you bothering telling me this?”)

Basically, it’s a world without (let’s call it) time-based complication. Nothing started happening at a certain point and then changed everything.

I sometimes joke with my students that, if they find themselves mired in this purely expositional mode, they should just plop this sentence in there: “Then, one day, everything changed forever.”

Then the story has to rise to that statement and, voila: boiling water.

I love his description of “the moment when the path of the story narrows.” When the scene setting ends and the writer works to focus your attention, and starts to bring the water to a boil.

That's it. If you made it this far, hit reply and tell me how you're doing and what you're up to this weekend besides watching the U.S. Open finals.

Still,

Michael

You just read issue #15 of sippey.com. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.