Welcome to today’s bucket of eels. I’m Rose. Let’s pull out some eels, shall we?

It's been a while since I've checked in with you folks. As a reminder, if you want regular emails, you can become a supporter of my work. Time Travelers get newsletters twice a month, book club discussions and meetings, bonus podcasts, special Discord channels, early and exclusive access to fiction, and more! I recently started publishing monthly installments of a young adult story, and members are the only ones who have access to a few short stories I've been working on.

Today’s eel: Every edition of this newsletter is named after an eel. Today's eel is Anguilla japonica, or the Japanese eel. We've talked about Anguilla eels before (here and here) and this genus is probably the one that people interact with most in their lives, albeit as a food source, rather than a living creature. If you've encountered Anguilla japonica it has probably been on a plate.

The key thing to know about the Anguilla family is that as adults they live in freshwater. But at earlier stages of their lives, they float in the vast and open sea. These eels actually go through five different stages of metamorphosis as they grow: from eggs, they turn into something called Leptocephalius, a flat and transparent little form that survives on marine snow. Eighteen months after becoming Leptocephalia, they grow into something called a "glass eel," which is slightly more eel-like in appearance but maintains that translucent, glassy look. As glass eels, they move from the ocean into the freshwater habitats that they'll spend the rest of their lives in and become what are called "elvers." This migration is linked to the tides and the moon, and always happens at night.

Once they're settled into their new, fresh habitats, the glass eel finally gets some color and turns into what's (uncreatively) called a "brown eel." This stage can last up to ten years as they eat (worms and insects mostly) and grow and slowly reach sexual maturity. Once they're fully developed (which again, can take ten years!) the eels turn silver and get a new, final name — again uncreatively just "silver eels." Only silver eels migrate to the spawning areas and reproduce.

Once they're settled into their new, fresh habitats, the glass eel finally gets some color and turns into what's (uncreatively) called a "brown eel." This stage can last up to ten years as they eat (worms and insects mostly) and grow and slowly reach sexual maturity. Once they're fully developed (which again, can take ten years!) the eels turn silver and get a new, final name — again uncreatively just "silver eels." Only silver eels migrate to the spawning areas and reproduce.

Most of the eel you eat is brown eel, not silver eel, and comes from farms in Japan and China — an industry that has only grown since its inception in 1894. And here's one thing that might surprise you: farmers still can't figure out how to breed these eels. So these farms go out and catch silver eels, bring them back to the farm, and raise their offspring up in captivity for food. According to a recent paper: "Of the 280,000 tonnes of freshwater eel that were produced for the consumer market in 2019, 98% came from eel farms, the remainder coming to market as wild-caught large eels."

Sadly, this section of the Wikipedia page about Japanese eels does not include information about eel music or sports.

The problem is that like its European cousin the Anguilla anguilla, the Japanese eel isn't doing so hot in the wild. Both the Japanese Eel and the American Eel are considered Endangered by the IUCN, and Anguilla anguilla is Critically Endangered, which makes its trade restricted by many countries. But when eel is prepared, it's really hard to tell which species you're looking at.

This is a very long leadup to what I actually wanted to tell you about: an interesting paper from this month which used DNA barcoding to try and figure out which species of eel was actually in eel products. When I was considering going to graduate school in science, I thought DNA barcoding would be the thing I might study. It's a really cool technique with a lot of applications! I had grand dreams of using it to understand ocean ecosystems better, particularly deep sea pelagic spaces. Of course, I didn't do that. Instead I'm writing you a newsletter about my journalism with a very long prologue about eels.

So anyway, the findings! The thing that's interesting about this paper is that they found that it's not Europe that has the highest rates of European eel in products, it's actually East Asia. Which means that these eels are being caught and shipped across the world, rather than processed and sold closer to home. Or, in the words of the researchers, "the results show a mismatch between the natural range of anguillid eels and which species are used in unagi products in each region." They go on to say: "This highlights the complexity of the international supply chains and how illegal fisheries and/or trade of the European eel may be occurring internationally."

Interesting!

An illustration from an 1856 manuscript called Notes on some figures of Japanese fish : taken from recent specimens by the artists of the U. S. Japan expedition

An illustration from an 1856 manuscript called Notes on some figures of Japanese fish : taken from recent specimens by the artists of the U. S. Japan expedition

If you want more about eels and DNA, here's a bonus thing: back in 2019 a scientist did a bunch of genetic work on Loch Ness and concluded that probably the Loch Ness Monster is actually just a big fucking eel poking its head out of the water. Last month, the Folk Zoological Society published their own take on the topic arguing that no, in fact, there is no way that the monster was (is?) an eel. In a press release, lead author Floe Foxon wrote: "In this new work from the Folk Zoology Society, a much-needed level of scientific rigor and data are brought to a topic that is otherwise as slippery as an eel." The rebuttal to the "big eel" theory essentially argued that the chances of finding an eel that large were too small for it to be reasonable.

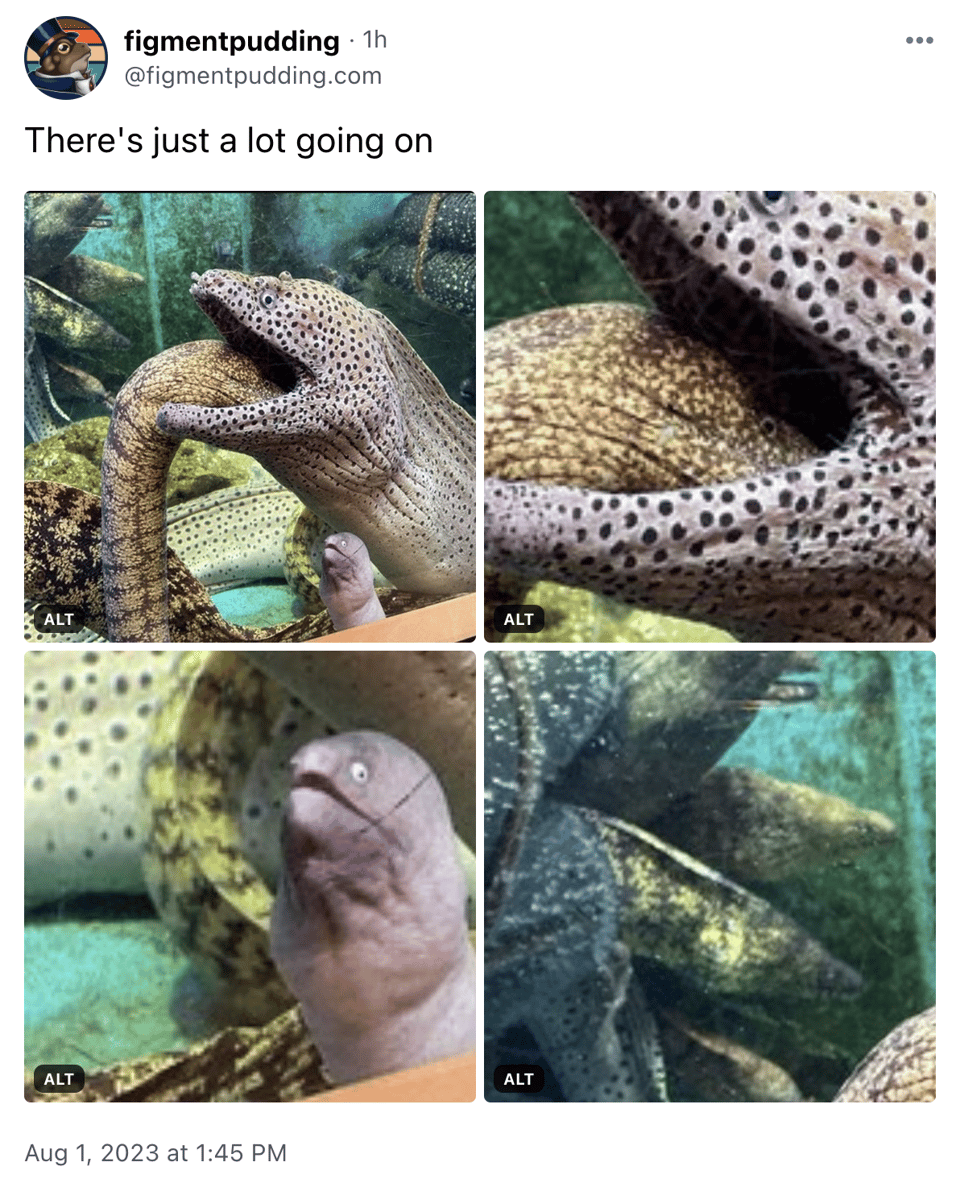

This image from the researchers at Otago university makes me giggle.

This image from the researchers at Otago university makes me giggle.

What I've Been Up To

A few wins since we last spoke:

A show I worked on was nominated for an Emmy!

Vanguard Estates was a finalist for a Third Coast Award!

I joined an art studio and made some fun pots!

I made some interesting art that is less commercially viable.

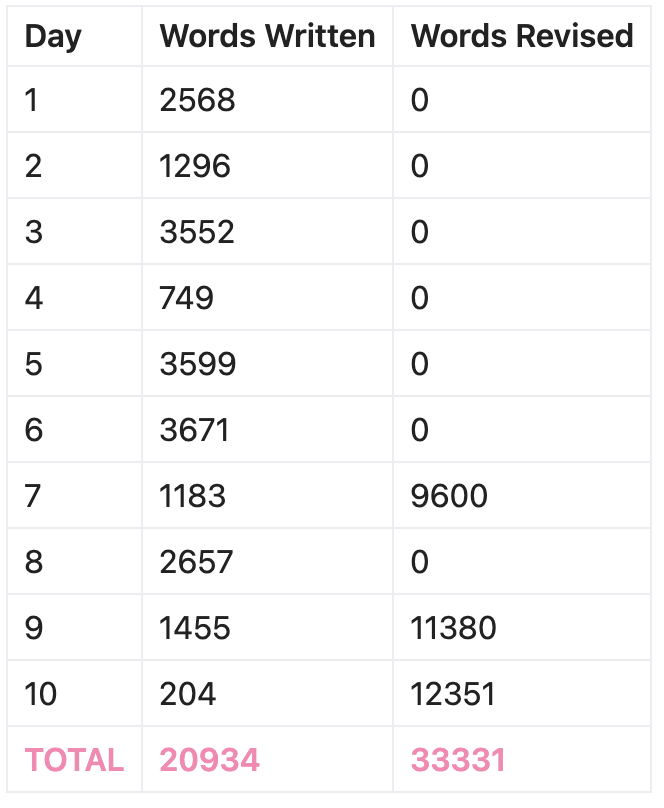

I wrote a LOT on a little writing retreat.

A few other things: I got a new book agent, and she sent me great notes on my book proposal and I'm really excited to dive in; I "quit" my column at WIRED (at least on a monthly basis) to make more space for fiction and other projects; I helped write and publish a guide on solidarity with WGA/SAG-AFTRA for podcasters; I made progress on finally selling a project I've been trying to get funding for for five years.

2023 has been an odd little rebuilding year for me, and I'm still trying to figure out how to answer the question "what have you been up to since Flash Forward ended?"

As you almost certainly know, Twitter (which I refuse to ever call X) is a wasteland. There are many things to say about the evils of Twitter over the years. It was the source of my own Worst Internet Moment (being targeted and doxed by 4chan dickwads) and also the source of a lot of Small But Still Very Bad Internet Moments. And also! It was where I met a lot of people I am genuinely friends with today. I had fun, and laughed, and connected, and "built an audience" and while that sounds gross it really meant that I found a community of people who were interested in the same things I was. Is that so bad?

Anyway, I'm not going to wax poetic about the end of Twitter. Other people have done that better. I don't know what happens next or where people go. If I'm honest, I'm feeling quite overwhelmed and confused by it all.

I'm on Bluesky, and I'm on Tumblr, and I'm on Cohost, and I have this newsletter, and I have Peach and Instagram and Facebook and TikTok and BeReal and Discord and there are things called Pillowfort and Grouper and Threads and Hive (I only made one of those up) that I'm also supposed to be on but am not. Maybe this is the end of a singular social media gathering place. Maybe that's ultimately good for the world, but makes me sad as I try to watch the Women's World Cup and miss the chaos and joy of a good World Cup Twitter Experience. Or maybe one of these will emerge. I don't know.

If you know, please tell me.

In the meantime, I'll reiterate that the best place to keep up with my work and support what I'm doing is by becoming a member of the Time Traveler club.

Bonus Eels:

You just read issue #22 of Bucket Of Eels. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.