Me and My Friends #63 - Californication

1.

Californication was released twenty-five years ago today, on June 8, 1999.

This is not a review of Californication, because reviewing Californication is like reviewing the sky; a sky that happens to be encased in a cliff-side pool. Californication has been there, above us, if not the whole time… then what feels like the whole time.

It’s familiar, a favourite jacket, a perfect memory, a part of every single one of our lives in ways both obvious and present, and distant and ambient. And not only that, the album is also an essential part of this band’s history. The reason they are still here. You can’t skip over this one. It’s… well, it’s inescapable.

To hear Californication once is to know it, and to know it is to love it. Though to hear it for the thousandth time is to reconsider it again, to wander into the high-ceilinged room where it lives, direct a little more mental attention to it and maybe find something new. There’s nothing I could possibly write that will get through the roots you’ve been putting down since you first heard the album, whether it be back in June 1999, from a tiny boombox in your dorm room, posters of N*SYNC and the Buffy ladies on your wall, or last week, from a tiny box in your living room, blasting 256 kilobytes of raw, Vlado Meller-squished AAC directly to your AirPods.

Californication is inescapable and immovable. Any attempt to say, in this look backwards, that it was overrated, or that it wasn’t actually any good, that it doesn’t deserve a seat at the table, is impossible. First of all, it isn’t true. But it’s like trying to convince you we don’t need the color green. How on earth could we live without it? We wouldn’t even be here today, sharing pixels, if it hadn’t come out.

Conversely, telling you how good it is also feels like a pointless exercise. You know it’s good. I know it’s good. They know it’s good. Newsflash: we’re all on the same page.

I’m simply knocking on the door, hands in the air, asking for a moment of your time. I just want to talk, is what I’m saying. Just enjoying the scenery.

Watching the sun go down as twenty-five years go by.

2.

Californication is the rebirth and the end of the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

The circumstances around its release is the rebirth, of course: John coming back, the band deciding not to throw in the towel after reaching the end of another road. It’s what gave them that extra push, gave them the opportunity to celebrate the lucky miracle that their friend returned from the depths of hell, that there was one of those movie moments, when the arm comes out of nowhere, catching them before they tumbled completely off a cliff.

And not only that, the fact that they wound up putting out their most successful album. They weren’t just saved; they were thrust beyond anything they had done before, commercially and - depending on who you ask - artistically. After all this time it almost seems like a cliche, like their story had been written by the same Hollywood that had birthed and nourished the band in the first place.

But Californication is also basically the end of the line as far as their story goes.

That doesn’t mean what they did afterwards wasn’t worthy (it is). It doesn’t mean that they aren’t still capable of making good music (they are). It doesn’t mean that they can’t still be an exciting band (they certainly can be). It doesn’t mean that I don’t continue to feel every note of their continued recorded history deep in my double-helix (I do).

It’s just that when Californication came out, they hit upon the golden formula, and what we’re seeing now is a continuation of that formula. Before, the band had frequent major shifts in their sound and their identity. Of course they did, what else could they do? They were children, a band who lost members like it was a hobby, moving from thrashing slap-and-scratch punk in the early, early days, to metal-infused funk at the end of Hillel’s stint. Between Mother’s Milk and Blood Sugar, they stripped themselves completely bare, quietening down virtually every element they possessed and then refining each of those elements. Then, with Dave on board, they explored their darker nature, extending everything that could be extended, and going through their “goth” phase, but also cherry-picking what they liked from - and this is the cleanest connection possible - prog rock (remember that “One Big Mob” and “Stretch” is actually one song).

Each album, from 1984 to 1995, was a different version of the band from, essentially, a fundamental level.

And then Californication came out.

They’ve had detours afterwards; By the Way went “poppier” and “moodier,” Stadium Arcadium went occasionally classic-rock-by-way-of-Jimi-Hendrix-inspired. The Getaway flirted with loops and electronic production, and took the band outside of their comfort zone.

But these are all variations on a theme that began when Californication was cooked up. Josh entering the fray in 2009 was a chance for things to get really different, but guess what happened after a decade of genuinely thrillingly, interesting, different-for-the-band music? They brought back the guy Josh replaced, the guy who made Californication. And what came next was two more albums that continued on with the kind of music the band started making in 1998.

I’m not complaining; again, we wouldn’t be here without it. And I’m not saying it’s formulaic, necessarily. And, of course, it’s no surprise that the same group of people are going to make things that feel connected, feel similar to each other. But consider the fact that the lead singles for Californication, By the Way and Stadium Arcadium all feature the exact chord progression of F, C and D in their choruses (and let’s call the verse of “Soul to Squeeze” an early hint of that). These are all different sounding songs; the slow and contemplative “Scar Tissue” doesn’t sound anything like the Sabbath-chugged power-punk of “Dani California.” But there’s close to zero chance that John Frusciante isn’t aware that these particular chords work well for Anthony Kiedis’s voice, that it’s natural and easy for him to build a song around that particular progression and that scale.

Californication was extraordinarily unlikely. The fact that it exists at all is a miracle. The songs are great. The playing is great. It’s the band’s most successful record by far. All of its tentpole singles are stone-cold classics, and it’s basically the only album in which every major single is still reliably played by the band live.

But it’s also the beginning of the band turning into construction workers, clocking into a shift, crafting their songs with care and precision, with passion, but with the blueprint pretty solidly in their heads; now, they know, and John in particular knows, what it means for a song to be a Chili Peppers song. These kind of thoughts started with Californication.

They know what they’re doing, and they can do it well. And boy did they do it well.

3.

The background context, the world this album was released into, is not just interesting but maybe key to the whole thing. It was 1999, the end of the decade, a decade that had done so much to popular Western music. Rap had continued to explode and become not just mainstream but the most popular art-form. Pop musicians had not only stuck around but re-asserted themselves, defended on the front foot against relentless mocking from virtually every corner of the planet and lasted until stumps. Grunge had necessarily white-blood-cell emerged in 1991, yes, but in the decade since, either its heroes were dead or they had become the same behemoths they were supposed to replace. Grunge might have killed hair metal, but something even worse was waiting to take its place.

The 90s, our 90s, the band’s 90s, this newsletter’s 90s, are bookended by two albums; Blood Sugar Sex Magik, and Californication.

When Blood Sugar Sex Magik was released, the number one album in the United States was Ropin’ the Wind by Garth Brooks. When Californication was released, the number one album in the United States was Millennium by the Backstreet Boys.

A lot changed, a lot didn’t. Almost everything changed, almost nothing did.

By June 1999, when the Chili Peppers had popped their heads back up and returned from the briefest of blips away, maybe the time had come to see what had happened as the dust settled on the decade and we all prepared for Y2K. Rock was still popular, but not in the way it used to be. Rap-rock had emerged; there was something for you here if that’s what you liked. Hell, the Chili Peppers had to spend most of 1999 and 2000 defending themselves against the charge that they were the reason rap-rock existed (they probably were!). Luckily for them, they had still become something different in their time away.

Maybe that’s why it struck such a chord. There was an appetite for a band who the public recognized, but who had changed in some way, who had freshened things up. Anthony was blonde now, his hair was gone; John was long-haired now, his hair was here! And not just here but fully Christ-like. But hey, Flea and Chad were the same, and the band were elder statesmen now. Things were different, but there they were: back, familiar, and with new entries to their canon.

Who else was going to headline Woodstock 1999 but the Red Hot Chili Peppers?

And when Californication was released, it’s hard to understate how damn enormous the band was in that next twelve month period. “Scar Tissue” was at #1 on the Billboard Modern Rock chart for sixteen weeks in 1999, “Otherside” was at #1 on the Billboard Modern Rock chart for thirteen weeks in 2000, and “Californication” was at #1 on the Billboard Modern Rock chart for a week in 2000. That’s thirty weeks; that’s over half a year, and in the space of only about a year. Picture the time period between January 1 and July 30: that entire time being dominated by one band being the most popular rock radio band. And that doesn’t take into account “Around the World,” which “only” reached number 7. No wonder people grew tired of them; no wonder they cemented themselves into the public consciousness.

But after hearing the album, really, it’s no wonder.

4.

Not everyone liked Californication on release. It’s a classic now, sure, arguably their best album (just like all the others), with endless avenues to explore, something for everyone and every occasion. But, initially, a lot of people deemed it too soft, a lot of people missed Dave, and a lot of people thought it was wimpy, that they had lost something, that they were a pop band now.

Take a look at any pre-1999 video of the Chili Peppers and 100% of the time there will be a specific type of comment. The person’s name will be something like Dickhead44. They may well have a flag - and not a good one - in their username. And they’ll be spouting a variation of: I miss this band, back when they used to actually rock. Now it's all tame/soft/rich-man ballads when John came back. Anyone else miss the funk?

That isn’t exactly - or even kind of - true; the band’s biggest ballad is from 1991, so surely the die was cast well beyond then. But Californication and its surrounding success cemented that version of the band in the public’s eye. Every album since has been greeted with an expectation, ahead of time, that this might be a return to their “glory days.” That they’ll go “back to the funk.”

There’s no denying that Californication is good, that we love it, that we’re all so glad it happened. What I find fascinating is that this is something we only know… because we know it.

Before John came back, before Californication, Dave Navarro was the guitar player for the Red Hot Chili Peppers, One Hot Minute was the band’s most recent album and… people liked it! It didn’t quite have the lesser-stepchild reputation that it has today. It got good reviews. It got bad reviews too, of course, but so did Blood Sugar. So did every album the band have ever released.

Rolling Stone called One Hot Minute “a ferociously eclectic and imaginative disc that also presents the band members as more thoughtful, spiritual — even grown-up. After a 10 plus-year career, they’re realizing their potential at last.”

Entertainment Weekly gave it a B+; it only gave Blood Sugar a B-.

This profile in Q refers to it as their “sixth and best” album. (Their review of Californication wasn’t nearly as positive.)

At the time, prior to his comeback, John was considered this kid who could play some mean guitar, and who made two great albums, but had gotten in over his head and blown his chance with the band; the drug stories only added to the sense of wasted opportunity. There are plenty of examples of people who were glad when he left in 1992; people who were glad Arik came along and started to actually play the songs properly again.

By April 1998, One Hot Minute had only been out for two and a half years; it hadn’t been tossed aside yet the way it has today. It didn’t sell as much as Blood Sugar had, no, but that didn’t mean it wasn’t any good. By the Way didn’t sell as much as Californication, but no one started complaining about guitar players then (and don’t get me started on the undeniable commercial bombs the new albums have been).

One Hot Minute was also very successful; any band would be lucky to sell as many records as they did: platinum in many countries, “My Friends” on the top of the rock charts for a full month, the album number one all around the world.

“Not only do I love that record,” says Dave Navarro, “but it remains the most successful record I have ever been a part of.”

Rick Rubin says: “The Chili Peppers were viewed as being on a downswing because the album sold only under however many millions. After Blood Sugar, no one had any realistic expectations and so One Hot Minute doing five or six mill - not to be sneezed at - is declared a flop.”

Five or six million! That’d be #1 in 2023. The Chili Peppers were everywhere in 1995 and 1996, and if they hadn’t run up against so much bad luck, if Chad hadn’t broken his arm right before a tour, if Anthony hadn’t relapsed over and over again in the lead-up to the album and then afterwards, it would have been even bigger. Their 1997 schedule, before the band really fell apart, had them headlining stadiums all through Asia. It wasn’t over until it was actually over.

And if it’s chemistry we’re talking about, remember this: Dave Navarro joined the Chili Peppers in October of 1993, and by June of 1994 they had started recording One Hot Minute. That’s pretty damn good! Those songs were written quickly. It’s only Anthony who prevented that album from coming out a full year earlier, and this whole story being a lot different. And if the same thing hadn’t happened in 1997, who knows how even more different their whole story would be now.

But this isn’t a review of One Hot Minute. My point is: when John returned, there’s this idea, especially now, that the Chili Peppers were over the hill, that they had disappeared and had lived in unlit obscurity during the Navarro era. But that isn’t really the case. Only during the year of 1997 - the end of 1997 - had that been even remotely true, and they’ve had plenty of years just as dormant since then without anyone worrying that they had broken up.

John being brought back into the fold was a massive risk. He had only been properly clean a couple of months and there was no telling how well he was going to cope with being back in the touring/performing/promoting saddle. He had played guitar constantly in his time out of the band, of course - and the idea that he hadn’t touched one since 1992 is not true - but his chops were definitely… rusty.

The key piece of media that signifies the post-return but pre-Californication era of the band is this bootleg of their September 20, 1998 performance in Stockton, California. Plenty of recordings from that tour exist, but this show in particular is the most complete. As the band kick off the then-unknown “Scar Tissue,” a song that is less than a year away from being the most well-known rock song on the planet (until “Smooth,” that is), and the crowd start to look at their shoes and the walls and talk to each other, a conversation between two attendees is picked up by the camera.

“His guitar tone sucks, it’s so muddy.”

At the end of the song comes the kind of polite, golf-clap response any band playing a new song will get. A year later and everything was different, obviously. But that was never a given. There was a time when the band playing one of their best, most celebrated, most well-known songs was treated with indifference.

Californication could have come out and done absolutely nothing. It could have sold maybe a million copies, maybe way, way less. If they were “on their way down” in 1995, who’s to say that wouldn’t keep happening? I don’t just mean commercially either. Artistically too. There are plenty of albums out there by once-enormous acts that came out, got digested by the planet, and then sort of disappeared.

Remember Zeitgeist by the Smashing Pumpkins? Me either!

Put yourself in the position of someone who adored One Hot Minute. Wouldn’t you be a little bit worried about what might come next?

I mean, yeah, sure, Blood Sugar was good, but that was seven years ago. They’re going back to the heroin addict? The guy who bailed on them once already? How long is he gonna stick around? I heard those solo albums he put out… weird, weird stuff. Wait - that’s him? He looks like a dang skeleton!

Here’s the end of a 1999 review of Californication from Melbourne’s The Age:

“Frusciante, who eschews amplification and melody, is the agent of change. On 1995’s One Hot Minute, [John’s] substitute Dave Navarro encouraged the band’s latent art rock tendencies. The result here is … well, the material is laced with harmonies, Flea’s bass is mixed well back and the album even ends with a Beatlesque ballad. Less ambitious than its predecessors, Californication is the Chili Peppers’ most focused effort and might be more enduring.”

That’s the kind of tepidly complimentary response a lot of people had. It was undeniably good, maybe even the best! …but there was a less bombastic quality to things, less sense of barely-held-together danger, less outrageousness, less of a spark, that might have wound up with people missing the good old days.

And so now what do you get? Dickhead44 wishing it was still 1987.

But he, thankfully, is in the minority, and hopefully more and more fans are able to take the band holistically, looking at them in their totality, instead of wishing for a past they might not have even been there to witness in the first place.

Californication wasn’t always destined to be a success. It wasn’t always destined to be many people’s favourite. It wasn’t always destined to be so good.

That makes it all the more remarkable that it was.

5.

So… Why is it good? This is the type of thing where words fall short, where the best case for something is the object itself. But I’ll try.

On Californication you have the band being the Red Hot Chili Peppers that they can’t help but be: the inner version of themselves that would come out, and does come out, no matter what.

On Californication you have the band reminding us of the fact that they can still be “themselves,” that - don’t worry - after all this time, they haven’t changed too much; this is very different from the version of the band that comes out unintentionally.

And on Californication you have the band doing something they’d never done before, a completely new vibe, a new method of songwriting. The same DNA in a brand-new dress.

But here’s the thing: that’s true of basically every single Chili Peppers album. But only on Californication do all of those versions of the band come out so successfully, so effortlessly.

These days, Californication is the one people tell you to start with. If you like Californication, you’re going to like the rest of the band’s discography. It has a looseness and a cohesiveness about it. The entire album was written quickly and recorded quickly. Even the song that they laboured over, the title track, was actually written and recorded virtually overnight; it was only its lyrics that had any sort of extended germination period. For all my defence of the Navarro era, there’s no suggestion that their chemistry with John wasn’t better, that in his return also came the permission for them to feel good about the band, to throw open the shutters and to enter into a kind of agreed-upon spring morning feeling that revitalized them. They knew that they were lucky to be there, and everything represented that, the music, the feeling of renewal, and Anthony’s lyrics.

Speaking of Anthony, I think another element that adds to the cohesion, the easiness, is the fact that he recorded his final vocals virtually alongside the rest of the album. That was the last time this happened; now it can be months before he’s done, because he typically holes up in some hotel room with Rick to complete them. And by the time everything is done and dusted, the spark is gone, the band are out of the particular creative space they had been in. For example: when John finally cracked the chords for “Californication,” Anthony was in the middle of recording his vocals. Meaning the band came back in to record the song at a moment’s notice. They wouldn’t always be in such a position to do so. I definitely think it’s reflected in his performance.

6.

A few random special moments or facts or feelings or thoughts from the album which have spoken to me while thinking about it recently:

The ending of “Purple Stain” going on and on, as Chad grows wilder and wilder, the corkscrew turning and turning. A virtuoso performance.

John’s solo on “How Strong” getting a blast of reverb added to it at the end (or maybe he just opens up a pot on his wah-pedal), turning it from a screeching hawk feedback to a heavenly choir as the final verse begins.

It’s only recently I’ve noticed this, but I had always found it a little strange that John performed backing vocals on “Fat Dance,” singing the name of Anthony’s then-girlfriend Yohanna Logan. A little intimate, isn’t it? Listening years later, it finally clicked that it’s probably Anthony doing those higher-register back-up lines, something he rarely does.

Flea’s bass line in the “Californication” solo, a part that isn’t repeated anywhere else in the song, and which takes a complete back seat but remains a key aspect of the song (something any bass player worth their salt is able to do). I mean, those arpeggiated bar chords, man!

The scream at the end of “Parallel Universe” that Anthony was clearly so proud of that they flew it in from the Teatro demo version. Rare for him to express himself in such a way. Guttural, emotional, pain-ridden, essential.

Like… all of “Bunker Hill.” The whole thing. Top 10 Red Hot Chili Peppers song.

What I think is a glockenspiel in the guitar break just before the final verse of “This Velvet Glove.” It’s mixed so quietly I’m not even sure it’s there, it could be weird harmonics from the guitar, but I think it’s some sort of percussion.

John’s dive-bombs in the final chorus of “Emit Remmus,” like he can barely keep control of the guitar anymore.

The instruments stopping at the “soft spoken with a broken jaw” point of “Scar Tissue.” That little pause completely opens the song up; listen to the 1998 version of it, and you’ll find it gets a little repetitive. Tiny fixes change everything.

The pure gall of “Gong Li” even existing. Half the song is a delicate, interwoven, plinky-sounding thing that may as well be a song about raindrops on lilypads (it’s actually named after this actress). And the other half of the song is a pretty straight ahead pop-rock song that not only has nothing to do with Gong Li the person (I think it’s about John and Anthony’s relationship in 1997-1998) but also seemingly has nothing to do with the other half of the song. And it’s not like it was a last minute thing; the song existed like that as far back as the Teatro demo sessions. Just two things barely related to each other, smushed together, living in perfect cohesion. It shouldn’t work, but it does.

The extra little vocal harmonies on “Porcelain,” like John coming in completely low and clean on “are you wasting away in your skin,” or the really high, barely in tune one on the final “alllll dayyyyy.”

If I do this again in six weeks, I’ll have eleven more little moments. If I do this again in six years, I’ll forget all of them, and they’ll all be new again.

7.

However.

I don’t love every little single moment of the album. One song in particular that I’ve grown to dislike - and for some reason it’s become strangely controversial to say this - is “Around the World.” It’s true! I’m sorry!

It wasn’t the opening track originally. “I Like Dirt” was in pole position in early drafts of the album, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the song used to open their shows throughout 1998. But, of course, by the time the album came out this song had to be it. The band moved it into opening position and in turn opened the album, their comeback, their statement of what the future would hold, with the quintessential Chili Peppers track. Everything that is amazing and terrible about them in equal measure.

The album beginning with that thick bass note driving into you and the rest of the opening crash, the entire band arriving like an exploding thunderclap, is cool, yes. And I do enjoy the outro. The band knows how to do a workout. I could listen to the outro as an entire, “In Love Dying” style song any day of the week.

But as the years go by, the less time I have for Anthony wasting his talents with things like the verse lyrics. They’re just… inane. They make me cringe, embarrass me, both personally and kind of on behalf of the fandom. His lyrics on the rest of the album are some of his best ever (“Get on Top” aside), and here it feels like he’s phoning in the “rap” persona, just mashing vaguely rhyming words together (like he does on “Get on Top”).

Those vocals, those lyrics, are all confidence. Only someone of Anthony’s pedigree, someone who is one hundred percent comfortable in his skin, could willingly put that on tape and, for the most part, get away with it. And I understand where he’s coming from: he’s seen the world and all the beautiful things it has to offer, and he wants to share the wonderful things he’s seen. He wants us to move past our differences and come together as one human race.

But, “me oh, my O, me and Guy O, freer than a bird, cause we’re rockin Ohio.” … Anthony, what are you on about? Are you talking about playing Gund Arena in Cleveland on March 12, 1996? Because that was the last time you played Ohio, buddy!

This all isn’t to say I don’t admire what the song is and does. In fact I have a perfect example of the effect the song - and the Chili Peppers in general - can have. It was January 18, 2013, and I was at the Big Day Out festival in Sydney. This used to be the Australian equivalent of… I suppose the closest example would be the old-school Lollapalooza. A traveling carnival, with a variety of stages and artists, headlined by a major (usually international) act. I’d normally avoid it and now do so completely (especially so because the entire thing went bust years ago).

I have several major memories with the Big Day Out, none of them particularly pleasant, be it the discovery that the ticket I bought on eBay for the 2008 rendition wound up being already-cancelled (the big black X the guy had drawn on the corner really should have clued me in). Or the time I sat in the deep bleachers of the main area, watching TOOL play the most boring, uninspired, head-down, zero-interest performance of my life, wondering why I had paid for this, wondering why anyone had.

Put it this way: I’m not a festival person. But the Chili Peppers were only playing the Big Day Out in 2013, and if I wanted to see them at all, I had to go. The other headliner, or I suppose I should say the runner-up, was the Killers. The stages were side by side, and as one band played, the whole crowd leaned as a nebulous blob from one stage to the other. You had to sit through a lot just to hear what you wanted.

The Killers' ascension in the mid-2000s missed me entirely. I guess “Mr. Brightside” is a fun and catchy earworm, but I couldn’t tell you anything else about them; I know there’s another big one - is it that “Somebody Told Me,” song, or is that just “Mr Brightside”? Gun to my head at this very moment; I have zero idea if they are even a band anymore, or what they have done lately. That’s the kind of knowledge I have of them. Two different universes.

But they were there before the Chili Peppers, and so I had to sit through them if I wanted a good vantage point. The Killers… were tap water. They looked like they didn’t break a sweat, and it was the middle of summer. Each song came out blissfully, perfectly, vanilla; no tempo variations, no explosions. Like Michael Buble with a very slight distortion pedal. It was like they were miming, and fifty thousand people were standing there in the setting sun watching. I’m pretty sure they had back-up musicians, but not in a good, this-will-flesh-out-the-sound way, but in a wait-can’t-you-play-your-own-songs way. It was an hour of the most un-rocking music of all time, basically a lounge act, leaving me so cold, so-unmoved, that I felt like something was wrong with me. People loved it; I felt like I was in a waiting room, which I technically was.

The Killers walked off stage to their waiting glasses of warm milk, and then a few minutes later, air thick with anticipation, the Chili Peppers came out. Within a few minutes, Flea - shirtless, drenched in sweat already - was doing his fuzzed-out bass solo/introduction to “Around the World,” and it could not have been more different to the band they had replaced. One rocked, and one “rocked.” Flea has at least fifteen years on the Killers’ bass player, but you wouldn’t know it from looking at them. And then, of course, the rest of the band arrived and did their thing too.

I know I’m a fan of one of these bands in particular, and that all of my feelings clouded my experience, but in that moment, watching Flea start the opening riff proper, I could exist outside myself and all of the knowledge and feelings I had going into that show and realise: wow, these guys really know what they’re doing. No wonder they were the headliners. “Around the World” helped me realise that.

But I just don’t like the verse! But I didn’t always feel this way. When I was fourteen, fifteen, just getting into the band, this song had its desired effect on me. I thought it was a wonder, a hilarious, bad-ass, “cool” track, that was everything great about the band. I have many, many memories of inhaling live footage of Anthony in that Californication-era white shirt and tie, Flea with that sparkling Modulus; it’s all tied together, the sound and vision. And in those pre-(but only just)iPod days, listening to the album (in a hands-off way, of course) had to be done in the order it was intended through a CD player; even the more-portable Discman tied you to that order (I mean they probably had a shuffle function, but who knows).

That meant I heard the song approximately eighty-four thousand times; I didn’t hear the entire album every time I started, and so that might just mean that I’ve heard this song more than any other Chili Peppers song, and that’s perhaps the simple answer as to why it doesn’t resonate with me all that much anymore. I’ve had my fill.

I’ll always have the fond memories. But now, in this headspace, in this bit of my life, it feels a little immature, a little goofy.

But to know this album is to love it. And I know it can be goofy, and I love it.

Songs I used to think were lesser in some way have actually grown on me. “Easily” never quite clicked with me back in the day, I think I used to think it wasn’t flashy enough, not realizing that it’s actually one of the hardest rocking moments in the band’s catalogue. It might be the song from the album I listen to the most these days; it not being very flashy is its strong-suit. It’s four guys in a room. It could be a Guided By Voices song, for Pete’s sake.

All this means I’ve changed while the album has stayed the same. Songs don’t remember us, we remember them, or we think we do, until we hear them again for what might really be the first time.

8.

At the time of writing, there’s been no suggestion (and no chance) that the band will be acknowledging this 25th anniversary in any substantial way (here’s hoping they do; this is one of those cases where being proven wrong is a wonderful thing). This isn’t exactly a surprise. In 2019, for the 20th, we had this god-awful picture disc, and to be honest, I’d rather have nothing at all than cheap tat like that.

(This section was written before this was announced. Not nice being right all the time.)

So, once again I’ve asked Leni from the RHCP Live Archive to put something together and take matters into his own hands. Chad speaking to the some lackey at the band’s SiriusXM channel is all well and good, but I think they can do a little better than that.

Every single thing in this collection already exists in disparate places… except a recording of the 9:30 Club show, of course, but who knows what might turn up. And - sure - rights issues might make some of the live shows hard to re-release. But you can pretty much already make this collection yourself now.

One day, hopefully, WB are just going to force the band to do something like this, in the proper quality that the fans deserve, and which the fans will pay for. Until then, let us dream… and remember that lesser bands with far smaller fanbases will put stuff like this out on a regular basis.

Californication 25th anniversary Super Deluxe Edition presented in a numbered, limited edition rainbow-foil box set with magnetic flap featuring new master, B-sides, outtakes, unreleased content, and live performances from the vaults over 9 LPs, 5 7-inch singles, 4 CDs, 1 cassette tape and 2 Blu-ray discs, digital download cards, tour laminates, lyric and setlist reproductions and a 120-page hardcover book with never before seen photos and stories from the band and those who were there.

LP 1 & 2: Californication 2024 remaster

The original album presented in a complete brand new 2024 remaster by Bernie Grundman, direct from the master tapes on 180-gram gatefold double LP.

LP 3 & 4: Teatro Sessions

Released in full for the first time ever, a collection of demos recorded in September of 1998 at El Teatro studios, an old converted Spanish language theatre, including never-before-heard songs that didn’t make it to the album sessions. Cover art features Anthony’s concept draft of Californication’s cover art.

More info/tracklist here.

LP 5: Live at the 9:30 Club

Straight from the vaults and available for the very first time ever, hear John Frusciante’s adrenaline-fueled return on June 12, 1998 in front of a tiny club audience.

More info/tracklist here.

LP 6 & 7: Live at Woodstock

Relive the band’s red hot performance on July 25, 1999, closing out the infamous four-day festival.

More info/tracklist here.

LP 8 & 9: Live in Buenos Aires

The final performance of the Californication era on January 24, 2001.

More info/tracklist here.

Album singles

For the first time ever, all the singles from the album pressed on 5 7-inch singles, featuring all studio B-sides from the album sessions.

“Scar Tissue” b/w “Gong Li” "& “Instrumental #1”

“Around the World” b/w “Bunker Hill” & “Instrumental #2”

“Otherside” b/w “How Strong” & “Slowly Deeply”

“Californication” b/w “Quixoticelixir”

“Road Trippin’” b/w “Fat Dance” & “Over Funk”

CD 1: Californication 2024 remaster

CD 2: Studio B-sides

As listed above and including “Trouble in the Pub,” “Californication [Ekkehard Ehelers Mix]” and various instrumental mixes.

CD 3: Live B-sides

Every live cut released on singles from the album arranged into a single playlist showcasing the length of the tour.

“Me and My Friends” - Stockholm, June 4, 1999 | “Yertle Trilogy” - Milan, June 14, 1999 | “My Lovely Man” - Rome, July 25, 1999 | “End of Show Brisbane” - Brisbane, January 24, 2000 | “End of Show State College” - State College, April 5, 2000 | “If You Have to Ask” - Darien, August 15, 2000 | “Blood Sugar Sex Magik” - Toronto, August 16, 2000 | “Californication” - Toronto, August 16, 2000 | “Under the Bridge” - Toronto, August 16, 2000 | “What is Soul?” - Portland, September 21, 2000 | “Search & Destroy” Portland, September 21, 2000.

CD 4: Radio & TV performances

Live performances for radio & television broadcasts throughout the era, such as Nulle Part Ailleurs, the Simon Mayo Session, the Chris Rock Show and the MTV Video Music Awards.

Cassette: Live from KBLT Radio

The band’s first appearance since John’s return, performing a low-key acoustic set at the iconic pirate radio station on June 5, 1998, hosted by Mike Watt and Keith Morris.

More info/tracklist here.

Blu-ray 1: Live in Red Square

Historic free show held by MTV at Vasilyevsky Spusk in Moscow, Russia, on August 14, 1999 featuring the full show including the songs omitted from the TV broadcast, enhanced in high definition.

More info/tracklist here.

Blu-ray 2: Live in Portland / Extras

Live performance from Portland from September 21, 2000 at the Memorial Coliseum released in full for the first time ever. Extras include the five video clips from the album, remastered in high definition with behind-the-scenes clips and commentaries. Also included, an extended cut of “Roadwork,” the documentary following the band during the Californication tour featuring over 40-minutes of previously unseen footage.

More info/tracklist here.

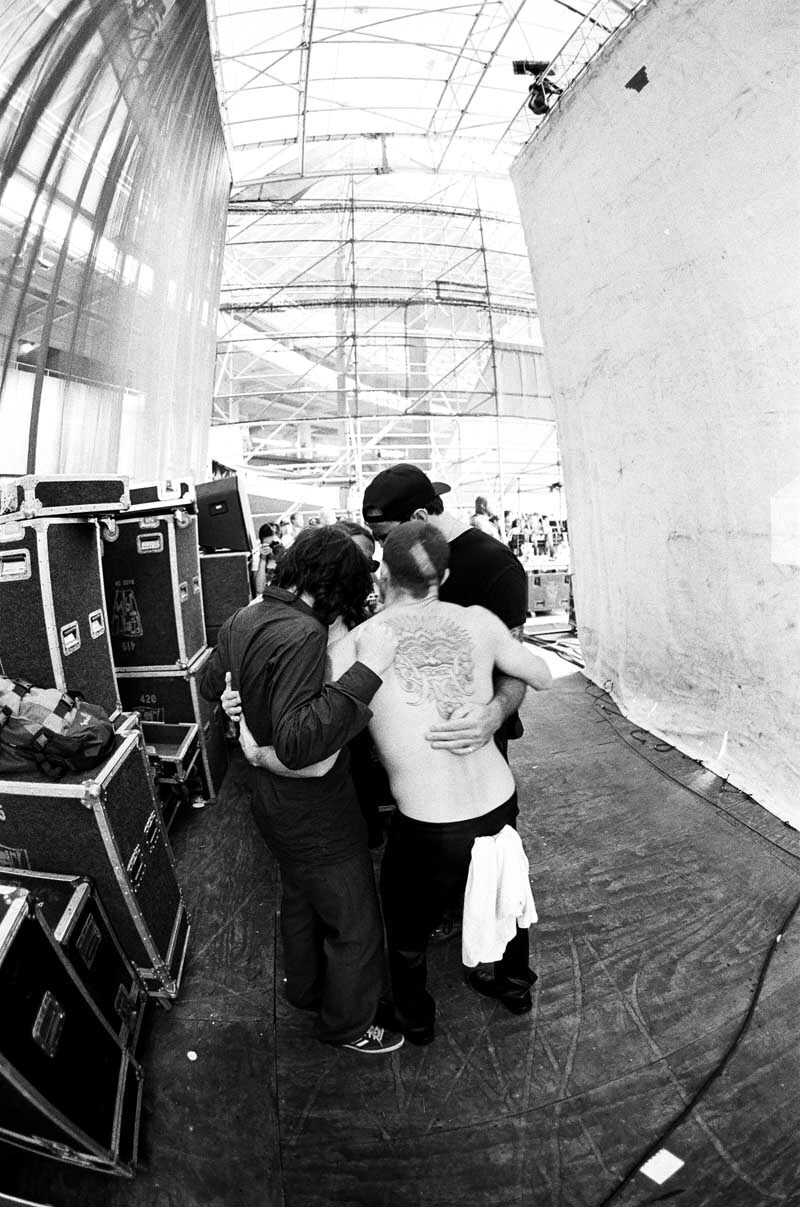

Phew! Thank you again to Leni for putting this together. You can see some of his other mock-ups in a previous letter here. I was equal parts delighted, equal parts devastated when I saw that image above for the first time. Truly, I gasped. It isn’t such an outrageous request….

9.

Let’s talk about how Californication sounds.

During the One Hot Minute era, the Chili Peppers luxuriated in the fact that Dave Navarro was involved. He showed up with his little goatee, and his sarcasm, and his nipple piercings, and his dry wit, and the rest of the band fell into line quite willingly.

They weren’t lying about what they themselves were going through; Anthony’s drug problems and Flea’s battle with chronic fatigue and relationship hell, and so on. It’s just that Dave being there allowed them to express all that in a certain way, and that certain way was: darkness. There’s literally the sound of a candle being lit on “Deep Kick.” Look at the “My Friends” video. The “Warped” video. The ending of “One Hot Minute.” The ending of “Transcending”! Those were some tormented boys.

“Warped” is a great song but a terrible first single. “Aeroplane” or “My Friends” really should have been first. But it was - probably - put out because it was the best example of the fact that this wasn’t the same ole Chili Peppers. They needed to differentiate themselves in some way. Welcome to 1995; halfway through the decade and it’s turned out… not great! River Phoenix is dead. Kurt Cobain is too: he blew his own head off. Nine Inch Nails’ perfect lovelorn techno angst were the most memorable thing at Woodstock. The optimism had started to wear off. Black was in… and “Warped” is a 180 degree pivot from the lightness of Blood Sugar.

That album itself has some darkness; the haunted mansion (I mean, there’s literally a ghost in the album booklet), “Under the Bridge” and “I Could Have Lied,” the fact that our only perspective of it is in black and white… But it’s still a lighter album than its successor. It has “Apache Rose Peacock” and “Funky Monks” on it; it’s light-hearted. The band were in a joyfulish place when it was recorded.

So, One Hot Minute was a “dark” album, probably in response to everything that had come before. What do you do when you’ve turned 180 degrees from something and it didn’t “turn out” the way “you wanted it to”? You turn back around, and go back to what worked for you last time. Sparseness - dryness - was on the menu. The sound of four guys in a room. Anthony, Flea and Chad were keen to get back to basics, and John was feeling vulnerable, feeling… whatever the antonym to flashy is, and that comes across in the sound.

How does one measure sparseness? It’s simple, really: overdubs. As By the Way came careening along, John had already become the in-studio wizard that we know and love today, and on Stadium Arcadium, if anything, and perhaps by his own admission, he went overboard with it. On Californication it was like he was scared to do anything at all. He didn’t want to cause a fuss.

When you think about Californication, do you think of overdubs? Cycle through it in your head now, please. I can wait. The vast majority of the album is a bass, a guitar, a set of drums, and some vocals. Whatever rare overdubs there may be are actually quite tastefully simple. A guitar solo in “Parallel Universe.” The slow strumming underneath the solos in “Scar Tissue.” The single guitar solo that emerges from the ether in “Get on Top” and then just disappears back into it. “Easily” ends with a self-described guitar orchestra, which seems like it would be a cacophonous din, but it’s really just three of four very clean-sounding guitars singing away over each other. The tiniest little beeps of a keyboard on “Californication.” The acoustic guitar on “This Velvet Glove,” which technically doesn’t affect the song at all, and could be done, and has been done, without it. The guitar solo on “Quixoticelixir” being straight into the board, muted, barely there. They even gave us a version of “Road Trippin’” without the only overdubs it actually has, as if to apologize for going above their station.

Is “Savior” the busiest song on the album? A bubbly guitar solo, the bells, ultra-audible backing vocals. Doesn’t that say something?

Pick any song from Californication and move it to a future album, and I don’t think it would sound the same, for better or worse. These sessions were lightning in a bottle, a moment in time that won’t - can’t - be replicated.

10.

We’ve talked about how it sounds, but let's talk about how it sounds.

Californication was recorded in a world-class studio, using extraordinarily expensive equipment, and engineered by a team of geniuses who knew exactly what they were doing. John, Flea, and Chad all used instruments that had been fine-tuned to within an inch of their capabilities and which were played by hands that had been born to do so.

So why does it sound so horrible?

Well, let me confuse things first and say: it does and it doesn’t. The basic, run-of-the-mill, 1999-to-present edition of the CD sounds horrible, of that there’s really no question. The original vinyl and cassette pressings are just as bad. The songs were digitally squeezed and digitally squeezed over and over again throughout the mixing process in 1999, that by the time they were finally mastered they were a solid square of digital distortion. But that sounds… fine, at least through tiny speakers, or a transistor radio while you’re at the beach, waves and seagulls in the distance. And remember that the album sold fifteen million copies; doesn’t that mean they did something right? Some have speculated that what helped Oasis get so popular at first in the United Kingdom is because their stuff was mastered so much louder than everything else at the time. When you can recognize one song over every other one at a loud pub, post-football match, pint in hand, of course it gets ingrained into the consciousness more.

In any other setting, with good headphones, or good speakers, or even just listening in a remotely quiet space, the faults with the 1999 version are obvious. I won’t belabour the point; the album didn’t become a poster child for the loudness wars for no reason. And Warner Bros. and/or the band are obviously aware of its reputation.

But the bare bones of the album - the raw recordings - are completely fine. It’s bandied about frequently that everything that sounds bad about the album was baked into the tape, but one listen to the multitracks proves that isn’t the case. It isn’t unsalvageable. They just went overboard back in 1999.

A lot of people also say the album needs a remix, which would be interesting, and which I’d listen to without question, but isn’t necessary. The original mix is what the band set out to do: it’s how it sounded in the studio before it was squeezed into a shape it shouldn’t be. It’s sparse, the way they intended it. It’s basically in mono, the way they intended it. Mono isn’t a dirty word. Listen to “Around the World” with a pair of headphones and every one of Chad’s drum rolls becomes so much more pronounced; they’re virtually the only thing in the song that isn’t panned completely in the centre. That’s kinda cool!

And what would a remix even do? Layer it with reverb? Push the bass up a little bit? Expand the stereo panning? (You can just do all that in Audacity now, if you like, not that it would sound any good) The album’s sparseness - drums, bass, one guitar and a vocalist - can really only be mixed one way anyway. And for all we know, the remix wouldn’t be any good, and we’d just be stuck with yet another inferior version.

(If we’re talking about albums that need a remix, can we start with By the Way? Maybe the flimsiest and tinniest Chad’s drums have sounded on record. Even John himself has lamented how the finished version of that album sounds.)

The original mix is fine, and you can hear that for yourself quite readily, because the Greatest Hits masters have been toned down a fair bit, the 2012 vinyl remaster of the album is superb, and from about 2014 or so, the version of the album that is available on streaming services is yet another remaster. This last version isn’t perfect, it’s… okay, but it’s quite a bit better than the 1999 original. Do yourself a favour and either buy the 2012 remastered edition on vinyl, or source yourself a high quality rip of that. If you don’t mind it being “out of order” and a little tinny sounding, stick to the Rough Mixes version, which many will be used to by now.

My key point is that it can, and now, does, sound better than the original mix and master. A carefully done, widely-acknowledged, widely-available remaster would alleviate virtually every problem that people have with the old version, and help people realize that there was nothing inherently wrong with the recording in the first place (the band would also get a lot of attention for remastering the infamously poorly-mastered album).

But hearing the original version of Californication is a kind of through-the-looking-glass moment. Or maybe a kind of They Live moment. Once you twig how bad the album sounds, you’re never going back. Elsewhere, you hear one cymbal crash turn into a white-hot sheen of distortion and all of a sudden every other cymbal is a symbol that something has gone very wrong, and that quite often, you can do something to fix it.

With the right - or wrong - mind, you might start investigating. You might learn about the Rough Mixes bootleg, you might perk up when you come across the word “unmastered” in other situations, you might start tracking down pbthal’s vinyl rips, you might listen to the Guitar Hero version of Death Magnetic, another Rubin production - ahem - which is less compressed than its retail counterpart, you might start and publish a fourteen-thousand word, sixty-nine page document that lists every different version of a Red Hot Chili Peppers song. You might come to know the difference between 16-bit and 24-bit audio and know you - as in I - can’t tell the difference between the two. You might come to learn that Bluetooth headphones are inherently lossy and so make UHQ files basically redundant. Before long, you’ve gone through periods in your life in which you’ve replaced every single album in your iTunes library with a rip of its vinyl counterpart (original pressings preferred) downloaded from what.cd. You’ll learn that quite often 1980s mixes and masters of albums are overly shrill because heavy cocaine use dulls your high-end hearing. You might still have XLD and EAC installed on your computer to this very day. And maybe you’ve then thrown all that away and reverted back to straight convenience; whatever Apple Music dishes out to you will be good enough, knowing that the occasional album will sound worse than others.

Maybe your experience will differ, but hell, that’s the journey I’ve been on. I’ve changed over the years, ping-ponging back and forth between mindsets and worldviews and levels of investment, but the knowledge that this album sounded so bad was the beginning of all that; some of this stuff is a curse, but mostly it’s a blessing.

The funny thing was, I had no idea it sounded bad when I first started listening to it.

11.

The first three CDs I ever bought with my own money were Californication, Rage against the Machine, and Appetite for Destruction. Well, that’s not actually completely true. The first CD I ever bought with my own money was the (surprisingly good) soundtrack to Roland Emmerich’s 1998 - Great? Awful? Both? - Godzilla. I was obsessed with Godzilla, that movie specifically, and bought every bit of tie-in merch a seven-year-old could afford; where that money came from, I have no idea, though I’m guessing a birthday or Christmas had something to do with it.

I have no memory of listening to the popular rock and rap music that graces that disc, be it [redacted] ruining a perfectly good Led Zeppelin song, or Rage Against the Machine cashing their check while dissing their employers at the same time. What I do remember is the final two tracks, selections from David Arnold’s orchestral score from the film, scaring the absolute living shit out of me: when listening to those tracks - for the first and only time - my blood ran cold, and I stood with my back against the wall of my closed bedroom door, getting as far away from the music as I could without actually leaving the room. Godzilla the movie didn’t scare me, but that music did. Who knows why, but I suppose it’s one of the first times music ever affected me in such a way, any way at all.

I don’t know what happened to that Godzilla CD. In the moment, I would have liked to peg it from a moving car, but I guess it just got thrown out years later, a forgotten item, something I moved past. Music as a real interest didn’t quite take hold for another few years. I haven’t heard the score since.

Five years later, the next CD I bought was Get Born by Jet, at a Fish Records store in Leichhardt, New South Wales, back in the days when CDs used to cost $32.99 each (Fish Records is long, long gone; I bought tickets to see the Chili Peppers there in 2007). If you were using a voucher - which I probably was - you could choose just one new CD, and not just choose a CD but agonize over it, because you had nothing left over, no useful change and the possibility of crushing disappointment if you chose wrong.

Jet, at the time probably the biggest band in the country, were and are derivative shlock, a group of suburban Australians who acted and dressed like they lived in mod London, boots and leather jackets and long hair and little cigarettes and all. Noel Fielding but without the jokes. They’re like the Rockabye Baby albums they make for children; it’s the same songs but for a stupider mind. “Are You Gonna Be My Girl” is just “You Can’t Hurry Love” and “Lust for Life,” without the joy of either of those genuine classics. Several years later I heard “Sexy Sadie” by the Beatles for the first time and realized that was where Jet had stolen “Look What You’ve Done” from: they were vampires, sucking the life out of what was good and giving the world a bloodless husk instead. In 2006, Pitchfork reviewed their second album, and instead of writing anything they just embedded a video of a chimpanzee pissing into its own mouth. Enough said.

But a year or so later, music - my own musical identity - finally clicked. I was a white kid living in the inner suburbs, so of course I latched on to mainstream rock music, and the Chili Peppers particularly. They weren’t the only ones, of course. All the other classics of the era were there; Rage Against the Machine, Foo Fighters, Guns N’ Roses, eventually The Beatles, then the deeper, deeper cuts, the beginning of a journey still going today. There are so many alternate universes where I’m sitting here writing a Foo Fighters newsletter, but there was something about our four boys, and particularly Californication, that connected with me and rang my little head like a bell. It helps that one of my earliest memories - ever - was watching the Chili Peppers. The sudden realization that that burned-in, blurry memory of staring up at our little TV in the kitchen and watching either the “Give it Away” video, or the band’s The Simpsons appearance, and then realizing years later this was the same band made it all feel like fate.

There were detours of course; I adored a lot of rap - I can still recite most of Eazy E’s “Real Muthaphuckkin’ G’s” off by heart - and I’ve had long relationships with other bands (I used to run a Deerhunter fan site), but I always returned back to the original little spark. Within a few weeks I had bought those three CDs I mentioned above, and the rest is history. I still love RATM, but I don’t have that album anymore, it just disappeared at one point. And I don’t really vibe at all with Guns N’ Roses; there’s a disconnect for me now looking at the teased-up hair and the tight pants and the “rock and roll” image, but “My Michelle” still slaps and always will.

Californication, however, rose to the top and stayed there. It was the first little drip, the first crack in the dam that meant everything else could come bursting through a short while later. Everything I’m writing today is connected to that disc arriving in my life. That sky blue CD went with me everywhere, played at any spare moment, devoured greedily. The band’s other CDs quickly followed as soon as my meagre income allowed, and there was no turning back. I was all in.

After I became a fan, I remember exactly what I was doing when I heard each new album of theirs for the first time: in my friend Mark’s bedroom as we pored over Stadium Arcadium’s booklet and argued with strangers over MSN chat who didn’t believe we actually had it; in my own bedroom five years later, as I’m with You premiered over that short-lived iTunes streaming feature; on a Bankstown line train at dusk after The Getaway leaked while I was at work; at the very desk I’m writing this sentence right now, headphones on, eyes closed, enormous glass of red wine at my side for Unlimited Love; making dinner while engrossed in Dream Canteen, not realizing I had accidentally put it on shuffle (rookie error), thinking it was brave to put tracks like “My Cigarette” and “In The Snow” so early on in the tracklist.

Each album is a specific point in my life. I was a different person for each of them (well, less so for the most recent two), in a different place, physically and mentally for each one. Specific songs hit in ways they can’t hit now. Specific songs helped in ways they can’t help now.

But I don’t remember hearing Californication for the first time. Any of the band’s first eight albums for that matter. It happened, obviously, but the memory wasn’t retained; I guess I didn’t realize at the time what kind of effect it was going to have. Those albums were the bulk I had to catch up on, and it feels like it all happened at once. In that sense, while it might be twenty-five years since Californication, it’s actually… infinity. If I wasn’t there to see it arrive, then all I knew was its presence. It’s been there forever. I entered the world, and it was welcoming me in like an older sibling.

All of a sudden, part way through 2005, I didn’t have that copy of Californication. I have no idea where it went, but I probably loaned it to a friend, or it ended up on the floor of my brother’s car, or… who knows. That’s the issue of physical media, I guess; you have to actually have it to use it.

With no real internet (long story), no iPod, and no streaming, and not the kind of disposable cash lying around that I could use to buy another copy, I just… didn’t have it. I had to either listen to my copy of Live in Hyde Park (hot take: it’s a bad mix!), or occasionally see one of the album’s videos on MTV. I don’t think I owned Greatest Hits by that point. And that was it. The entire album disappeared into the rear-view mirror of my memories, and the others nudged into the free space it left. Blood Sugar was always my favourite album in those early days, probably because it was actually there. This album, on the other hand, became a blind spot. I started to miss it, then I started to forget it. The pre-release period for Stadium Arcadium fired up and in the excitement for the future, I paid even less attention to the past.

Months later, I was at a friend's house, a friend who had the internet at home and a spindle of blank CD-Rs on his computer desk, and after we had finished watching pirated 360p episodes of LOST, I had him, almost as an afterthought, burn me a copy of Californication. I took the blank CD-R - no text, I would know what was on it - and made my way back home from Marrickville on the 445 bus holding it out in front of me like some precious grail. A few hours later I found myself in my room, alone, on my single bed with its lime green bedspread, with this poster above my head, my CD player on the side table next to me, and remembered I finally had Californication again. It was a shock, a gift from myself from only a few hours previous.

I could hear the clicking of my parent’s dress shoes on the tiling outside their room, the smell of my mother’s perfume. It meant they were Going Out. In my memories of those times, I only found out about those expeditions of theirs as they were leaving. It was always a surprise - a pleasant one - because it meant I had the house to myself. A movie on the good upstairs TV, music up as loud as I wanted it, ridiculous amounts of coffee that never seemed to affect my sleeping pattern.

Once they were gone, I closed my bedroom door and put the burned CD-R of Californication in. There were no phones, no distractions. I lay back and let it arrive. Or return, I should say.

Every song was a sudden, precious memory of an old friend. Something so familiar; deeply, bone-level familiar. But as my brain had done the best it could to wash clean my memories of the album, it meant I was surprised and delighted all over again, as if hearing it for the first, and most potent time. The absolute dime-tightness of “Parallel Universe.” The soft and melancholy “Scar Tissue.” “Otherside” being a dark, goth-pop song in disguise. “Porcelain” the breather that every album needs. “This Velvet Glove,” “Purple Stain” and “Savior” being maybe the band’s best three-song run. “Road Trippin’” proving that the band are capable of anything. That night was almost twenty years ago, and I’m still there. A satellite circling that moment still.

The burned CD-R is obviously landfill at this point, and I got my original copy back from wherever it had been eventually. It’s still here, with its worn case, ancient, faded JB HI-FI price sticker (that I clearly tried to remove at some point, then thought better of it), a spiderweb of scratches on the disk. Still sitting along with all of its brothers and sisters, carried from my childhood home to every random share house and then proper house I’ve ever lived in. Boxed up, on display, in use, gathering dust. It will be there until… well, why would I ever get rid of it now? When it’s been there so long?

I may not have been there, present, twenty-five years ago, but I’ll be here for the next twenty-five. Happy birthday, old friend.