Me and My Friends #16 - Funkus Amongkus

Hi all,

In honour of the late, great Andy Gill of the incredible Gang of Four, this month I'm sending out a piece about the band's first album.

I wrote this a few months ago as part of a vague early attempt at beefing up the album's sessions page, with a plan to write something similar for all of the albums going forward.

Instead of doing that, I'm going to make pages for each individual song. That's a work in progress...But I still have this piece for the debut lying around, and I spent a bit of time on it -- even sending questions to Jack Sherman -- so I figured it could find a home here.

The album is a strange one; some of it is incredible, and unlike anything I've ever heard, and some of it is really dated and cardboard sounding. Being able to hear the demo versions of "Out In L.A." and "Green Heaven" have completely ruined the album versions for me, and "Baby Appeal" remains one of the most turgid, plodding yet catchy atrocities the band has ever released. But it is what it is, and I'm thankful we have it there on our phones and in our collections. They wouldn't be the band they are now without it. And if you've never given it a real listen, I hope that can change.

(There are a number of footnotes below, so it might be worth reading this entry on the web page, as opposed to in your email client.)

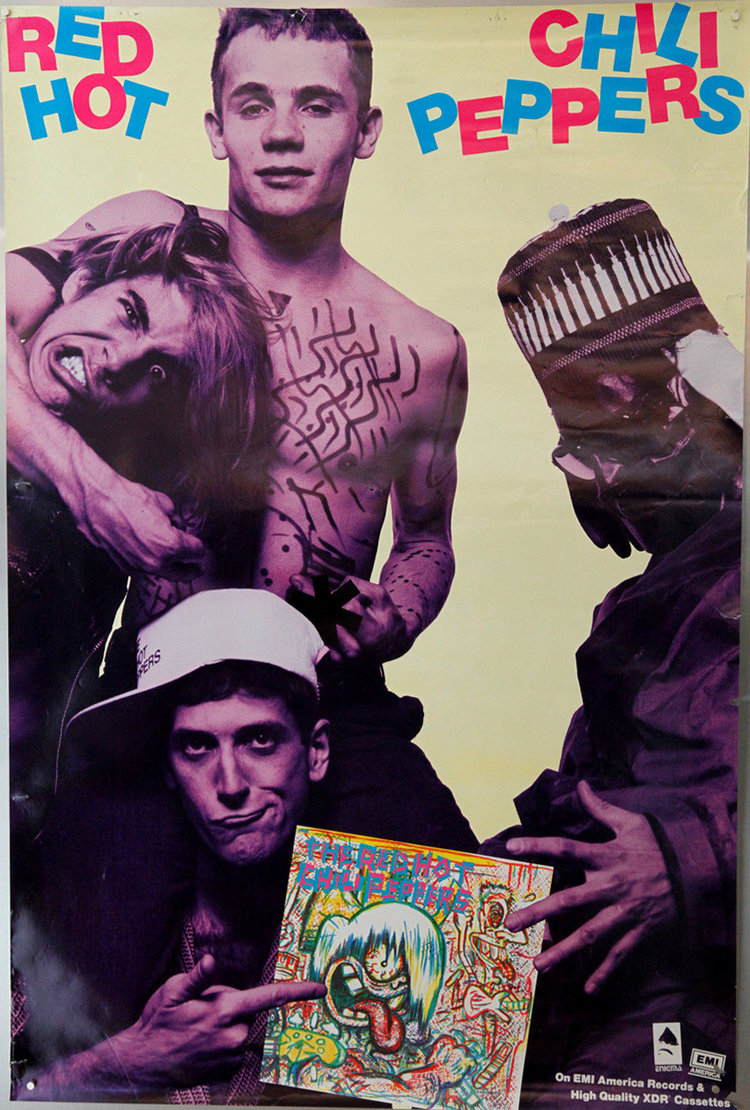

The Red Hot Chili Peppers

In April 1984, the Red Hot Chili Peppers entered Eldorado Studios in Hollywood to record their debut album.1 At the time, El Dorado was located at 1717 Vine Street, near the corner of Hollywood Boulevard, and had been operating since 1954. In recent years, the studios had been used by Talking Heads, Herbie Hancock, and What Is This, whose guitarist Hillel Slovak and drummer Jack Irons had left the Red Hot Chili Peppers in the later months of 1983.

Andy Gill, of Gang of Four fame, was brought in to produce the record.2 This was an exciting experience for Kiedis and Flea; Gill recalled that they “told me that the reason they formed was because Gang of Four was their all-time favourite band,”3 and in later years Flea himself wrote that they “completely changed the way I looked at rock music.”4

The recording sessions began after a period of pre-production that was held at SIR Studios in Santa Monica Boulevard.5 Quickly it became clear they were not to proceed as harmoniously as was first hoped. Flea and Kiedis clashed not only with producer Gill but with Jack Sherman, their newly-hired guitar player. After a searingly energetic and productive demo session in May 1983, one can imagine that the relatively sluggish pace that awaited them during the album sessions rubbed Flea and Kiedis the wrong way.

Further to this aggravating slow pace was the introduction of drum machines and digital effects, suggested by Gill and welcomed by Sherman and new drummer Cliff Martinez. Even standard procedures like the use of a click-track was considered a step too far:

At one point, Anthony grabbed one end of the drum machine and I grabbed the other. Anthony's saying, "Man, this thing has no fucking soul!" "Of course it's got no soul!"

"Yeah, but it's like 1984!"

And he was trying to grab it so he could smash it. In the end, we compromised with a click coming off it and Cliff Martinez, the drummer, would listen to the click and tap it out, which would make it "human," and then we worked with that click that he made. [laughter] Whatever works, you know! They felt better about it because there had been an intermediary. 6

Kiedis and Flea had desired to make an album that was simply a reproduction of their live show, similar to their original demo, but this was not to be the case. “Andy said he didn’t think you could take the live show and put it on vinyl,” Sherman remembered shortly afterwards.7

Regardless of whose intentions were best placed, Kiedis and Flea were correct in stating that the album fails to accurately depict the Red Hot Chili Peppers as they stood at that point in time. Where the spring 1983 demos were all cut live in one take, and possess an energy that would be near impossible to recapture, the album is classic 80s; sheen, rigidity and triggered frying-pan drum sounds. That said, perhaps their objections would have been better received had they been more on the conciliatory side; the story of Flea defecating on a pizza box and providing it to Gill has been repeated in enough detail elsewhere.

Most of all, naivety was rife. “They were these kids who’d never been in the studio before so had no idea how anything worked,” Gill remembered. “One time I tried to put compression on Anthony (Kiedis’s) vocals and he couldn’t understand what I was trying to do. He’d say ‘I was it to sound bigger, not smaller!’”8

Kiedis didn’t disagree with this assessment. “It made no sense to me,” he wrote in his autobiography, twenty years later. “I didn’t really know what the hell a producer did.”9

Kiedis also felt that Gill didn’t appreciate the spirit of the band; that he only wanted to make a hit “at all costs.” 10 Martinez agreed: “Andy was in a different headspace; he really wanted to make a commercial record.”11

They clashed not just personality-wise but over the choice of songs, too:

One day I got a glimpse of Gill’s notebook, and next to the song “Police Helicopter,” he’d written “Shit.” I was demolished that he had dismissed that as shit. “Police Helicopter” was a jewel in our crown [...] Reading his notes probably sealed the deal in our minds that “Okay, now we’re working with the enemy.” It became very much him against us, especially Flea and me. It became a real battle to make the record.12

Kiedis’s description of the sessions is perhaps unfair; Gill, Sherman and engineer Dave Jerden13 may have had a different idea of what the album should be, but they did the best they could considering the circumstances. The battle was two men (and their engineer) under contract to EMI, against a 21-year old Kiedis, who was seemingly absent a large portion of the time regardless. Sherman would state that without Gill’s contributions, the album would be “14 minutes long.”14

Wavelength Magazine, December 1984

Wavelength Magazine, December 1984

In later years, Flea would acknowledge the misplaced aggression and naivety that he and Kiedis displayed during the sessions. “It was our first album, and we were totally naive about what a producer did,” he said. “Instead of suggesting to Andy what we really wanted out of a guitar sound or a drum sound, we’d just walk into the control room while he was experimenting, and say things like ‘This sucks!’ We should have been asking, ‘Can’t we try something else?’ – but we didn’t know.” 15

Elsewhere, he lamented how the album turned out, but understood it was all part of the experience: “Anthony said many years later, ‘If that record would have been great we would never be together today.’ He’s dead right. We never would have survived this long, and because of it we’ve grown over time.” 16

If there’s one passage that could adequately describe the recording sessions, it’s perhaps this one from Dave Thompson’s 1993 biography True Men Don’t Kill Coyotes:

To Gill, the Red Hot Chili Peppers were inexperienced brats whom he had to mould into commercial shape; to Anthony and Flea, Gill was uptight, overbearing, and had no idea whatsoever of what the Red Hot Chili Peppers was really about.17

Sherman deserves a vast amount of credit for the role he played in the band’s early years. Bullied relentlessly, cast aside, and then unfairly erased from their history, not only did Sherman have a hand in writing the majority of the debut album, but he also contributed to seven further tracks that would appear on 1985’s Freaky Styley. They would not be the behemoth they are today without his efforts.

The Red Hot Chili Peppers is eleven tracks long, but contains five tracks that had already been recorded by the Slovak & Irons lineup of the band during their demo session the previous year: “Get Up And Jump”, “Green Heaven”, “Out In L.A.”, “Police Helicopter” and “You Always Sing The Same”. Interestingly, on the album those tracks don’t credit Slovak or Irons as writers, but perhaps this is a result of the pair signing a deal with MCA Records (as part of What Is This) at the same time that the Red Hot Chili Peppers signed with EMI/Enigma.

Further, “Baby Appeal” dates from prior to Sherman and Martinez joining; the band wrote the track after they travelled to New York in May 1983, and found that in particular, toddlers seemed to respond to their music more than anyone else. But strangely enough, Sherman and Martinez and Slovak are given writing credits for that track. Whatever behind the scene dealings went on to result in these credits are unknown, but a pre-Sherman version of the track with Hillel on guitar sounds fairly similar to the final album version.18

The first track on the album, “True Men Don’t Kill Coyotes” emerged out of one of the first jams that Flea, Martinez and Sherman had together. According to Kiedis, Los Angeles legends X were the lyrical inspiration for the song.19 Though not released as a single, a video was recorded for it; the band then used the props from the video on stage that night at a show at the Roxy. It was first added to MTV rotation in late October 1984, and on one of its rare airings a young man named John Frusciante watched it on TV at his home in Chatsworth, CA.20

“Why Don’t You Love Me” is a Hank Williams cover, the first in a long line that the band would record and release on their studio albums. The original, written by Williams, hit #1 in May of 1950. Bob Forrest, soon to be of Thelonious Monster fame, introduced the band (specifically Kiedis and Flea) to Williams. Strangely enough, various publications have confused the cover for an original. 21

“Mommy, Where’s Daddy” is another track that emerged out of a jam. The track “has a lot of things that are special about it,” Sherman remembered. “Flea, Cliff and I put the music together fairly easily and quickly at rehearsal. It was a bit more funky and groovy than some of the other material which tended more towards intense punk and hard rock. Then when we went to demo it was the first time I heard the lyric/vocal. I was blown away and told Anthony how great I thought it was. A little bit creepy lyrically but not over the top. Flea used to sing the little girl part and that was really funny.”22 Flea actually recorded vocals for the album track, but they were replaced with a performance by Gwen Dickey, of Rose Royce, just before the album was mastered, to the supposed complete surprise of the band. 23

The last track on the album -- “Grand Pappy Du Plenty”24 -- is an instrumental, and was crafted in the studio; Gill is given a writing credit. It’s unlike anything else on the album: spaced-out, sparse, and atmospheric. Finally, here was a moment of unity: everyone involved looks back on the song with fondness at its weed-addled recording. 25 Almost exactly ten years to the day after The Red Hot Chili Peppers was released, the band would open their set at Woodstock 1994 with a truncated version of the track.

One track that was recorded but not released was “Human Satellite”, a supposedly rhythmically stiff composition that was conjured up at the request of Gill. But the results were unsatisfactory, “terrified”26 the band, and as of yet hasn’t been heard outside of the sessions. As far as Jack Sherman remembers, it wasn’t even finished, and never felt natural. 27 However, the track is listed on the band’s BMI catalogue, so it was prepared for release at one point (probably ahead of the 2003 reissues).

Two tracks from the band’s early days, “Sex Rap” and “Nevermind” didn’t appear on the album. It’s unclear why; perhaps Gill advised them against recording such uncommercial tracks, though Sherman recalls that most likely demos were recorded. 28 These two songs would, of course, finally appear on Freaky Styley.

After the bulk of the album sessions were completed, some small amounts of overdubs were recorded at Baby O Recorders, which were located at 6525 Sunset Boulevard. Today, that space goes by the Hollywood Athletic Club; the studios were shut in or around 1986.

(The building that held Eldorado Studios is now this garish hotel/club combo.)

Initially, the band hoped to call the album True Men Don’t Kill Coyotes, and also toyed with the name There’s A Funkus Amongkus. 29 Ultimately, it was given the self-titled treatment, and was released on August 11, 1984. Commercially, it did very little, charting at #201 on the Billboard 200 30, and disappearing from sight shortly thereafter. To date, the album has sold approximately 630,000 copies worldwide, but most of those arrived after the album was reissued in 2003.

The only supplemental release from these sessions was a 12” remix of “Get Up And Jump (Dance Mix)” and “Baby Appeal (Club Mix)”, remixed by Rob Stevens and Steve Bando respectively. Rob Stevens mixed the rest of the album.

As for Steve Bando: no information about him exists at all, unless he’s this guy.

As I mentioned in a recent newsletter, I was sure that the band's first gig with John after his return wouldn't be in May, and would most likely be somewhere in LA, in a very casual setting, in early 2020...

One thing of note; the band played Gang of Four's "Not Great Men." In an Instagram post mourning Gill, Flea mentioned that he and John had just recorded a cover of the track for a planned Gang of Four tribute album (perhaps with Chad and Anthony, or maybe just the two of them [but then who played drums and sang?]).

They've played that track a bunch, but one of the most special performances came on June 5, 1998.... John's other first gig back.

My favourite Gang of Four song.

(Book update: 29,000 words.)

Until next time,

-

I’m unable to find a primary source for the recording date. A Los Angeles Times article from February 1984 states that the album was due in March, but also mentions that they hadn’t started recording yet, so that doesn’t quite make sense. Wikipedia states it was April, but also provides no source for that claim; Jack Sherman told me that April felt right. ↩

-

Also considered was Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek. ↩

-

Andy Gill, Tape Op, May 2009; specifically they were big fans of the song “Not Great Men”, which the band (or perhaps just Flea and John) recorded recently, and which the rest of the band played live in early February. ↩

-

Flea, The Guardian, 7 January 2005 ↩

-

Some early demos were recorded during this period at Bijou Studios. ↩

-

Andy Gill, Tape Op, May 2009 ↩

-

Jack Sherman, Musician, January 1985 ↩

-

Andy Gill, Gigwise, 17 September 2016 ↩

-

Anthony Kiedis, Scar Tissue, pg. 140 ↩

-

Anthony Kiedis, Scar Tissue, pg. 143 ↩

-

Jeff Apter, Fornication, pg. 84 ↩

-

Anthony Kiedis, Scar Tissue, pg. 142 ↩

-

Jerden was fresh off producing Hillel Slovak and Jack Irons with What Is This, and would end up mixing Mother’s Milk, among many other classics. ↩

-

Jeff Apter, Fornication, pg. 80 ↩

-

Flea, BAM, September 1991 ↩

-

Flea, An Oral/Visual History of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, pg. 149 ↩

-

Dave Thompson, True Men Don’t Kill Coyotes, pg. 79; for more, read pages 148-149 of the Oral/Visual History. ↩

-

Perhaps Sherman simply added enough to that final track to warrant a writing credit. ↩

-

Anthony Kiedis, An Oral/Visual History of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, pg. 150 ↩

-

Frusciante’s guitar teacher, Mark Nine, tried out for the Chili Peppers around the time Sherman joined. ↩

-

Laurie Kammerzelt, Artist, 1984; Jeff Apter, Fornication, pg. 92 ↩

-

Jack Sherman, interview with VeniceQueen.it, February 2011 ↩

-

Jack Sherman, interview with Max Efimov, February 2018 ↩

-

The name is an ode to Tomata Duplenty, Los Angeles club DJ, and vocalist for the Screamers. ↩

-

Jeff Apter, Fornication, pg. 94; Anthony Kiedis, Scar Tissue, pg. 144 ↩

-

Jeff Apter, Fornication, pg. 84 ↩

-

Jack Sherman, interview with Hamish Duncan, May 2019 ↩

-

Jack Sherman, interview with Hamish Duncan, May 2019 ↩

-

According to Laurie Kammerzelt in an interview with the band in Artist, 1984; Jack Sherman doesn’t recall discussions around the name, but said Funkus rang a bell. That name is probably in reference to this track. ↩

-

Billboard, October 20, 1984 ↩