OW #8: “Who Can Afford to Be Critical? What Can Criticality Afford?” by Afonso de Matos

In this issue of Other Worlds, Netherlands-based Portuguese designer and researcher Afonso de Matos looks back at his educational journey which led him from having no idea about design to believing that everything is design and design is everything. This journey urged de Matos to come to terms with a series of contradictions about the role of a critical attitude in design, its effects on the world and its relation to uneven professional opportunities.

Among a small but significant number of design institutions (mostly located in Europe, the US and the UK), a certain outlook upon the field has been taking shape. It has been given many names, but here we’ll call it “Critical Design.” This outlook perceives design as more than a market service: it aims to show that designers can be agents of powerful social and political change, beyond the boundaries of the commercial client-commission setting. From this perspective, designers are no longer meant to solve problems, but rather frame them. We are asked to shoulder the responsibility of raising awareness about the world’s issues. We are encouraged to become provocateurs.

These apparently productive developments beg, however, some further investigation. Who can afford to do this type of critical work? What standard does it set for the remaining 99% of designers who must work for clients in order to pay their bills, many times bound to unregulated working conditions? Or is that even those who do critical work are sometimes equally precarious? And that’s not all. Beyond asking what the criticality discourse does to us, designers, we must also ask: what can it really do to the world? Are our critical projects changing anything or are they, ironically, doing the opposite and keeping the status quo? What are the limits of awareness-raising? Whose awareness is actually raised? By which visual and material means, and within which spaces?

My thesis, developed at Design Academy Eindhoven between 2021 and 2022, entitled Who Can Afford to Be Critical? What Can Criticality Afford? aims to understand what political power contemporary designers hold and question this very understanding. Instead of focusing on individual critical practices that can quickly fall into echo chambers, should we rather try to look for political agency in other capacities? Maybe not as designers, but as workers, as citizens, as activists… simply, as people?

First of the t-shirts commenting on the critical design discourse and its cliches are to be worn by some DAE graduates as they present in the Graduate Show of Dutch Design Week, in October 2022.

Circling Around the Critical

I enrolled in a Communication Design bachelor program blindly. I had never heard of it. I had been treading through an oppressing, rigid path in the STEMs field for the past three years of high school, and the escape that a so-called “creative” field posed was alluring. I had no idea what graphic designers did – even though I dealt with and consumed objects designed by them daily.

When I was 17, in my final year of high school, I underwent a vocational assessment – one of those intensive tests where, at the end, you are told what it is that you do best and show more enjoyment doing. My top scores leaned more to the arts and humanities, instead of the sciences. It only confirmed something I already suspected: I should change my path. But where to? The psychologist who interpreted the results for me whispered a suggestion: “You know a degree which combines the visual arts and reading, writing and communicating? It’s called Communication Design, and there’s a nice faculty where they teach it here in Lisbon.” I was dumbfounded. I had never considered the existence of such a thing. He asked “Do you know what it is that communication designers do?” The only thing that came to my mind: “Hm… those billboards you see on the highway?”

Even though I started my bachelors having almost no clue of what graphic or communication design was, I finished it thinking that design was everything, everywhere. From the nowhere of invisibility to the nowhere of omnipresence, design’s culture seems to stride between these non-places. It behaves like a force that is barely recognized by most people even though it shapes their lives. This cognitive dissonance is ubiquitous within the field, with designers claiming that “everything is design” and “everyone can be a designer” while at the same time trying to protect their profession from the gig economy, from platforms where you can order a poster online for 5 euros, from the menace of technological automation and from amateurs – those with no professional training who can become equally as good as formally trained designers, given the ubiquity of online tools, tutorials and software.

Fanzines resulted from a series of meetings organized in DAE between February and May 2022, where students discussed how matters of finance, class and precariousness limit or enable how “critical” one can be through design itself. The four themes are: the reality of work beyond school; the power of design and the agency of designers; the labor and class position of designers, and the possibilities for designers to build collective power. The image displays three work in progress iterations.

At my bachelors, me and my colleagues benefited from quite experimental studio courses throughout the three years, where we could explore mediums such as sound, photography, video and installation art, while simultaneously having theoretical courses that aided conceptual thinking. We would both produce and design our content, content which would very often address various social, political and cultural issues. These social concerns were always present and we were encouraged to pursue them in our works, many times disregarding ideas of “good form” or “good design” in favor of a more thorough conceptual research, in favor of a pertinent message. This pleased me, given that I was quite passionate about activism – and silly young me thought that reading some theory and then doing a critical design piece addressing a social issue equated activism. When I learned that in this expanded view of design there was also a place for those urgencies, it felt like unearthing a treasure. I really loved my bachelors because of this. I could engage with politics, I could be critical!

Thinking in retrospect, the Communication Design programme, like many other European design programmes, seems to lean towards the third mode of criticality that Ramia Mazé ascribes to design practice in her contribution for the publication The Reader (2009).1 In the text, Mazé proposes three different modes of criticality within design. The first is an individual designer’s criticism towards their own personal practice. The second relates to criticism towards design in general, to its methods, culture, frameworks and dogmas. Then, the third mode relates to the cases in which design addresses urgent social and political issues. Here, in contrast to the previous modes, design itself isn’t so much the object of criticism as it is the vector through which this criticism is directed elsewhere. We can witness this framework at play in a whole gamut of recent approaches, sporting names like Social Design, Speculative Design, Design Activism, Design Fiction, Contextual Design, all of which could vaguely fit under the umbrella of this third modality.

A similar formulation to Mazé’s definition can be found when Els Kuijpers talks about productivism, in her proposal for a spectrum of strategies within communication design.[kuijpers] Kuijpers puts forward a set of five nomenclatures – functionalism, formalism, informalism, productivism and dialogism – which she argues are not “meant as a historical classification of styles with distinguished ideological positions but as a flexible scale in which the designer constantly shifts – depending on the circumstances.” Productivism, according to Kuijpers, “puts communication design at the service of a social programme aimed at bringing about change in society.”

Second t-shirt from the series that will be presented during the Graduate Show of Dutch Design Week in October 2022.

The research object of my thesis (or at least its starting point) is defined along these lines, and I will simply call it Critical Design.3 This name serves as a container for all those approaches that – following Kuijpers’ and Mazé’s definitions – aim to use design as a vector for social critique and social change, and see the designer as a political actor. Under this banner I could include many instances, for example, most of the projects produced within schools such as the Design Academy Eindhoven or the Sandberg Instituut’s Design Department (as well as their pedagogical ethos)[schools]; design studios such as The Rodina or Dunne & Raby; events like the Forms of Inquiry exhibition or the Istanbul Design Biennales; publications like Keller Easterling’s Medium Design; or micro-polemics such as the ones that stemmed from the Republic of Salivation project at MoMA’s Design and Violence exhibition.

Third t-shirt from the series that will be presented during the Graduate Show of Dutch Design Week in October 2022.

All the instances mentioned above have in common a view of design as an emancipated discipline which is capable of doing something beyond its commercial boundaries, and they perceive designers themselves as the stewards of progressive change. They share the common trait of trying to exit the usual model of design as a service, veering away from the demands of the market in search of a greater social good. They stem from research programmes, from funds and grants, from positions within academia – either as student, tutor or researcher – or just as the result of an “independent” practice (as in, independent from clients). However, these approaches do not necessarily circulate outside the market, but instead on an exclusive market of their own. In their eager criticism of the workings of the outside world, these projects often forget to examine what are the socio-economic conditions that enable their own existence in the first place – that enable the existence of such a thing as Critical Design. Where do these projects circulate? What makes them circulate in certain spaces but not others? What kind of audience do they attract? How are they financed? Who gets to engage with them? What does that engagement lead to? Does it lead to anything?

What It Does to Us and What It Does to the World

I finished my bachelors with a “Speculative Design” project: a fiction that proposed an alternative reality where humanity had evolved to become a collective hivemind. This was a group project, done with my friends Inês Pinheiro and Vítor Serra. As our degree came to a close, the anxieties started to pile up. As proud as we were of our project, when we looked at the maximalist aesthetics, cloudy lyrical language and the installation art medium it employed, we couldn’t help but pose two simple but grave questions to ourselves: “what can something like this really do to the world?” and “how can someone make a living doing projects like this?” Still, today, I believe the essence of these questions – as simplistic and naive as they were – is one worth pursuing. I believe it’s within these two questions that we can find the two barriers Critical Design faces: on one hand, the relevance that it can have to society and on the other hand, the feasibility of its practice for each designer, in such a precarious field. By reworking those two questions a bit, I arrived at these interrogations: Who can afford to be critical? And what can criticality afford?

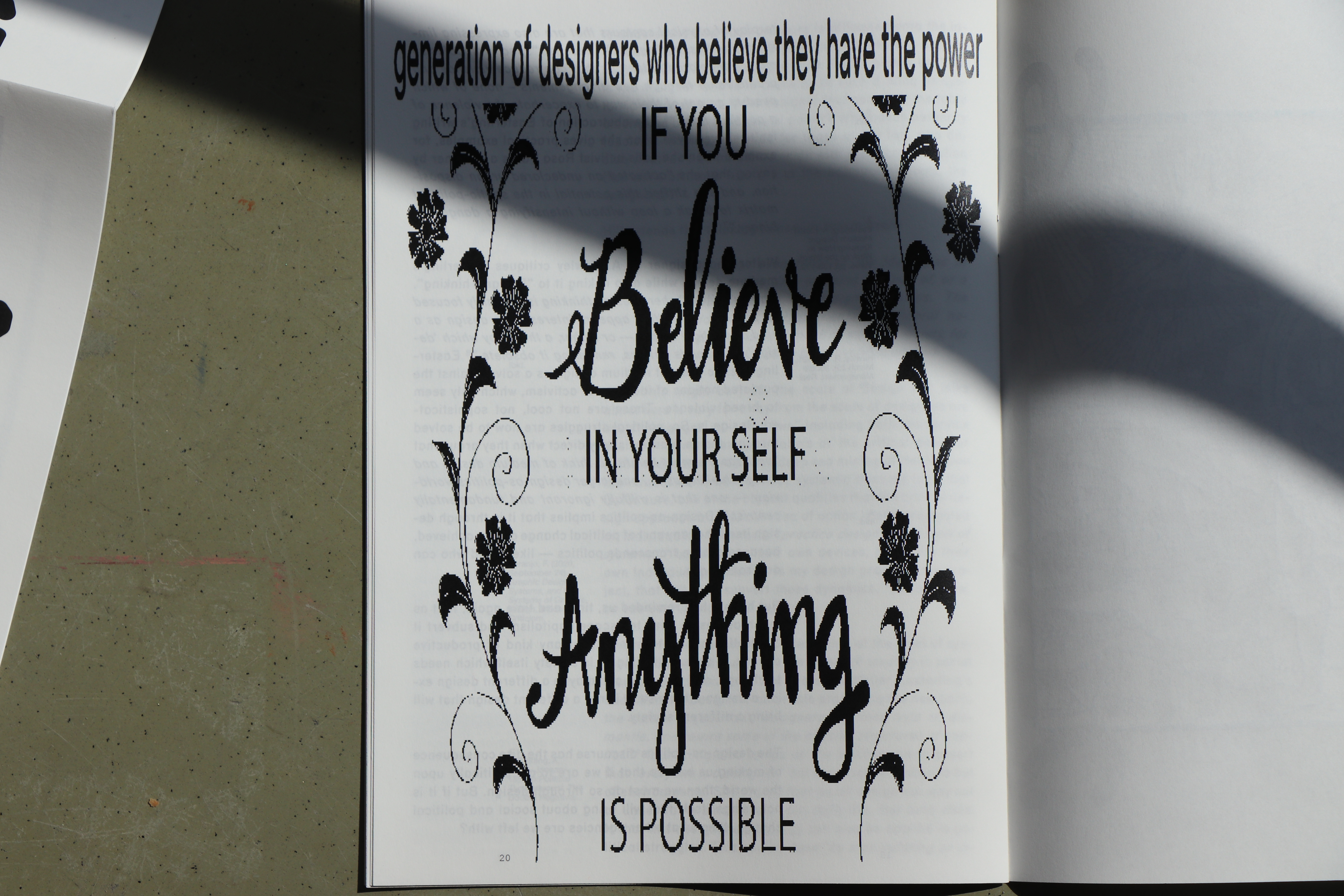

Page from the fanzine n. 2, entitled “I tried to subvert capitalism with my design practice. Now I’m looking for a job.”, which discusses what power and responsibility designers hold today.

Asking two questions allows for a dual analysis. The first interrogation highlights matters of privilege: why is Critical Design exclusive to a minority of designers who can conduct self-initiated, independent, critical projects, while the great majority of the profession doesn’t have the choice to do so, as they depend on a client, company or agency who pays for their labour? The second question focuses on the impact that critical discourses on design have upon the real world, outside of the profession – and on the very origin of the urge to have an impact on the world. Does Critical Design exist because designers want to use their skills to enact progressive social and political change? Or are there other historical contingencies that can explain this almost philanthropic drive? Is there a hidden (or better, subconscious) agenda?

At this point, it becomes clear that the age-old concern regarding what we can do to the world as designers is what fuels my research. If we can do something, will it be through Critical Design projects that target social and political issues? Or will it be through a different way of being critical, maybe one more aligned with Mazé’s first and second modes, where criticality is directed towards design itself, in the hope that by reflecting on design’s own mechanisms we might understand how they already impact the world? In other words, can one craft a critical practice of design, which is different from Critical Design? Would such a critical practice limit our agency even more? What is the relation between design’s power and the designer’s agency? What if instead of discussing how to impact society with our designs, we discussed first how we can impact our own world – our own field, one teeming with competition, precariousness and professional insecurity (of which Critical Design itself might be a symptom)?

Other Worlds is a shapeshifting journal for design research, criticism and transformation. Other Worlds (OW) aims at making the social, political, cultural and technical complexities surrounding design practices legible and, thus, mutable.

OW hosts articles, interviews, short essays and all the cultural production that doesn’t fit neither the fast-paced, volatile design media promotional machine nor the necessarily slow and lengthy process of scholarly publishing. In this way, we hope to address urgent issues, without sacrificing rigour and depth.

OW is maintained by the Center for Other Worlds (COW), at Lusófona University, Portugal. COW focuses on the development of perspectives that aren’t dominant nor imposed by the design discipline, through criticism, speculation and collaboration with various disciplines such as curating, architecture, visual arts, ecology and political theory, having in design an unifying element but rejecting hierarchies between them.

Editorial Board: Silvio Lorusso (editor), Luiza Prado, Francisco Laranjo, Luís Alegre, Rita Carvalho, Patrícia Cativo, Hugo Barata

More information can be found here.

-

Included in the Iapsis Forum for Design and Critical Practice, which also gave rise to the exhibition Forms of Inquiry (2007) at London’s Architectural Association. ↩

-

Kuijpers, E. (2016). Style? Strategy! On Communication Design as Meaning Production in Laranjo, F. (2017). Modes of Criticism 3 — Design and Democracy. Eindhoven: Onomatopee. pp. 19. ↩

-

Critical Design was coined by product design duo Dunne and Raby in the late 90s. They define it as follows: “Critical Design uses speculative design proposals to challenge narrow assumptions, preconceptions and givens about the role products play in everyday life. (...) It is more of an attitude than anything else, a position rather than a method.” In this text, the usage of Critical Design will encompass this definition but also Mazé’s and Kuijpers’ contributions to defining this critical shift we’re witnessing within design discourse. ↩

-

I could include others such as RCA’s former master programme Design Interactions; UAL’s MA Graphic Media Design; Yale School of Art’s Graphic Design MFA; KASK’s Autonomous Design BA + MA; etc. ↩