OW #20: "The Parable of the Coconut: On Kamala Harris’s 2024 Campaign Strategy" by Noemi Biasetton

In this issue, Noemi Biasetton examines Kamala Harris’s viral hype-based campaign, which aimed to engage young voters through meme culture and the “brat” aesthetic. She highlights the strategy’s adaptability and appeal but also warns of potential backlash from forced trends and unconvincing attempts to sway a savvy online audience.

Other Worlds is currently seeking sponsorship. If you’d like to support us, get in touch at s [at] silviolorusso [dot] com.

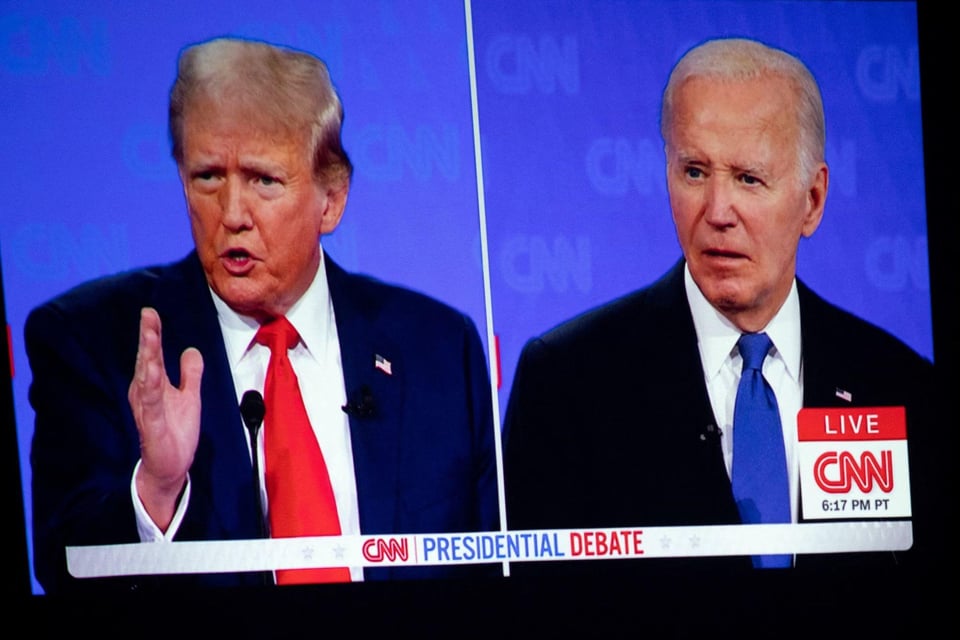

On July 21, 2024, for the first time in fifty-six years, Democratic candidate Joe Biden gave up his bid for reelection after realizing that his chances of winning were dwindling by the day. The decision was highly anticipated by the Democratic Party since June 27, after Biden’s disastrous performance during the CNN presidential debate against Donald Trump. After months spent talking about the alleged inability of the two contenders to represent the United States in the international context, especially in the face of the current geopolitical scenario, Harris’s incoming nominee brought a breath of fresh air that could awaken the left-wing electorate — as well as reactivate the Spectacle machine. Indeed, one of the main expectations hanging over the democratic candidate was to turn the tide of an election campaign deemed “boring” and trapped in a “geriatric circus”, and to surface the issues of this election from the blanket of media fog.

In the five months preceding the elections, Kamala Harris faced a pulse-pounding campaign, where she was given only a few months to establish herself as a public figure (especially internationally) and build a narrative that simultaneously debunks Trump’s lies and attracts new voters. After dominating the journalistic scene for more than eight years and being the subject of numerous analyses among the most various and diverse study fields, Trump seemed to be facing an impasse from a communication standpoint, which did not evolve much from the systems already adopted in the previous two campaigns. That was, at least, until July 13, 2024. In contrast, Kamala Harris fielded a number of new strategies that could have earned her a new slice of voters, especially in the younger demographic. However, as I will briefly summarize in this article, the experiment proposed by Harris' communication team already contained the recipe for a backlash, which proved particularly dangerous to the construction of a new party identity and a possible electoral victory.

Bratala

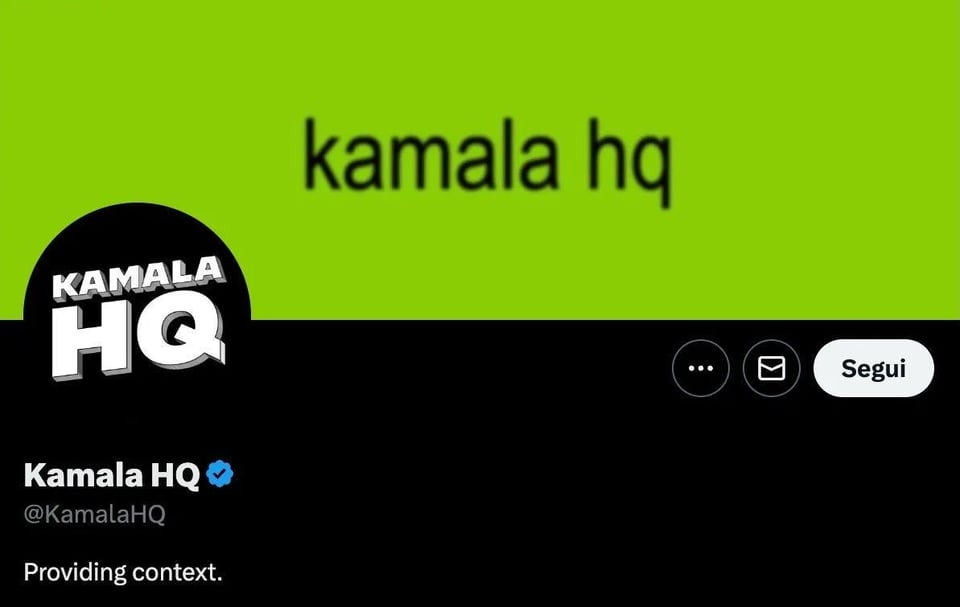

The first notable change in the Democratic campaign assets has been the implementation of a new design in Kamala HQ’s X official page inspired by the notorious album “brat” by Charli xcx, who on July 22, 2024 tweeted “kamala IS brat”. It would be extremely reductive to state what “brat” is or means, since the concept album released by the British pop artist — together with the response elaborated by the listeners — ignited a temporary cultural niche equipped with specific atmospheres, sounds, visuals and attitudes. What is now certain, however, is that “brat” delivered to the public something they yearned to hear. Through the use of an ironic (and iconic) double album, song remixes, and the visual design of her promotional campaign, in fact, Charli has opened up a critical reflection on the contemporary music industry that can be expanded to all aspects of life. In an age marked by digital representations focused on hyper-consumption, workaholism and anxiety, “brat” unmasks the rigidities of a capitalist system designed to fail real-life success, where the only weapons against an economically and socially collapsing world proposed by the performer are sisterhood and mockery of power. Through the album’s tracks, Charli xcx blurs the boundaries of the real and digital worlds, offering us a confused and unhinged way of life in which she expresses herself via a micro niche of belonging (something that is not new in the music scene per se, but that resonated strongly with the general public).

If we adopt this interpretation of the “brat” cultural phenomenon (which, like every micro niche only lasted a couple of months at best), it appears obvious that the same “endorsement” to Harris by Charli cannot be read as a canonical support from an artist to a candidate, but rather as a joke in and of itself. By this I mean that — as we all knew — we did not see Charli perform at a Democratic rally; nor did we see Kamala Harris approach a “brat” lifestyle. In this sense, the adoption by Kamala HQ’s X official page of the brat aesthetic fits the dictionary definition of meme, that is the decontextualized use of a single and shared unit of cultural information subjected to a specific influence.

The Politics of Temporary Aesthetics

At the same time, the move played by Harris’ communication team fitted a new modality of branding which is changing the idea of campaign management at its very core. If we look at the choices behind the democratic campaigns of Obama and Clinton in terms of visual appeal, it is possible to notice a strong imprint from the design team — with the logos designed by Sol Sanders and Michael Bierut and recognizable visuals carried out coherently throughout the campaigns. Usually, there’s a deep desire by designers to set a trend, to make sure that their logo and expensive brand identity is utilized in the way it was intended in the brand manual. However, it is now remarkable how the “classic” logo of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign (for example) proved not suitable for confrontation with a candidate such as Donald Trump, who went beyond all possible rules of the political game.

A defining trait of “classic” branding is precisely the concept of identity, which aims to carve a strong and memorable idea of a certain brand or product in the consumer’s mind. This is not just achieved through logos, but also with the overall visual identity designed by a singular or group of professionals. Over time, brand identity development has evolved along with the media landscape, updating on the concepts of responsiveness, adaptive narrative, and brand voice. However, the underlying concept remained the same: it must be design that inspires users to produce artifacts correlated with the brand, not the other way around.

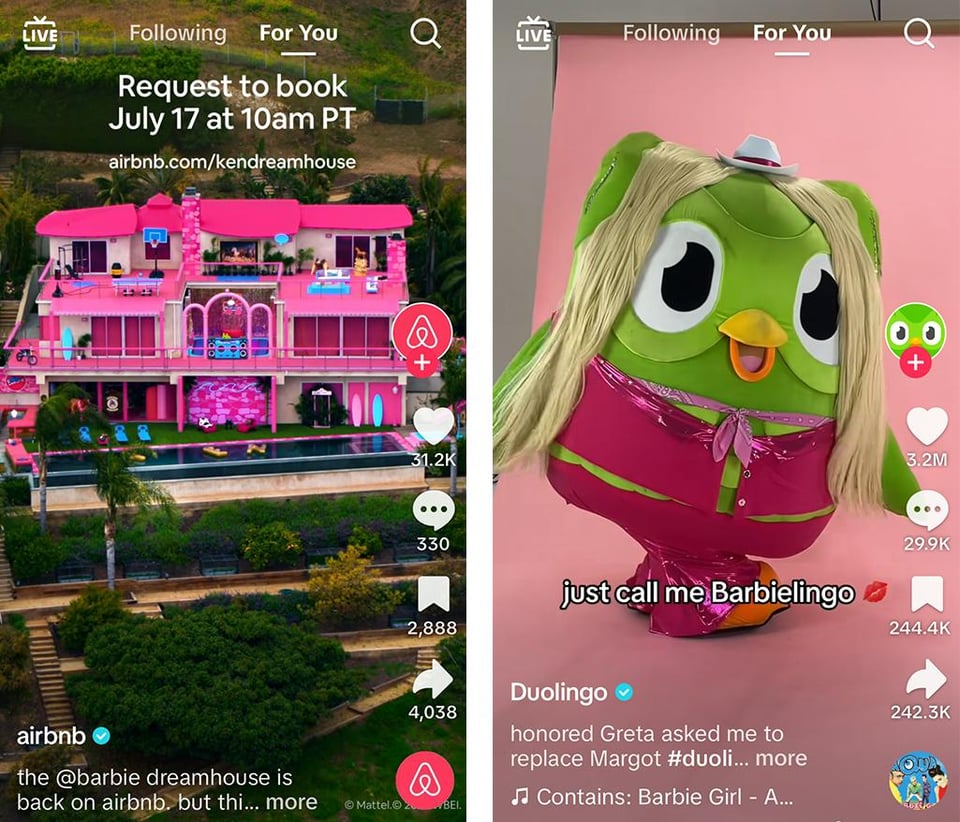

The decision by Harris’ communication team to adopt a current viral trend and turn it into a recognizable feature of a political campaign represents an unicum in the history of US visual politics, but it’s not new within the contemporary communication strategies adopted by marketing teams. In fact, in the last couple of years we have witnessed how many successful brands have turned to the use of specific online trends and/or aesthetics, adapting their products to this or that new upcoming set of visuals.

In a video series on TikTok created by brand strategist Eugene Healey, titled “Post-millennial trend”, the expert perfectly sums up the central issue of this new wave of branding by stating that, in today’s media matrix, “The creative tempo is different”. In fact, as suggested by Healey, we could say that “the new media landscape has compressed fixed identities down into temporary aesthetics”, where the imprint left by the brand is in the management of the visual niche they briefly inhabit. In a moment in history where people look at their lives through eras, brands also leave behind established design in order to accommodate multiple narratives — even if very diverse and sometimes discordant.

However, when brands try too hard to impose new aesthetics, trends or opinions, they tend to reach the pinnacle of cringe (Emily in Paris docet). In this regard, in a video-analysis of Charli xcx’s use of media, content creator @theeswiftologist stated that, today, it is the internet that “controls what’s cool, and it is simply too porous and expansive in the niche age to be controlled by only one sphere of influence”. At the same time, the risk of this campaign approach is that by trying to bring the younger generation together, the overall strategy ends up with the opposite result. Indeed, the co-option of viral trends by a party of this size automatically marks the end of its existence as a niche reference. About this topic, @theswiftologist speaks about the innate ability of online users to understand the authenticity of a certain approach to niche aesthetics, and affirms that “The Kamala coconut edits with brat fancams were genuinely funny until her presidential campaign caught on and started using it to their own advantage […] and we, the audience, the plebeians, the normal people who are just trying to have a big inside joke on TikTok, are immediately aware that Kamala Harris does not care about the spirit of “brat summer”, she cares about finding young people and getting something from them: their votes”.

To the Window, to the Walz

Another very interesting aspect of the 2024 US presidential elections is the massive media attention that has been given to the choice of vice presidents, who in this ballot seemed to acquire a prominent role in the fate of campaign results. After Harris announced Tim Walz as running mate on August 6, the comparison with JD Vance immediately fueled up online, with many users noticing how laid back and relatable he was compared to Trump’s VP. Besides, from what we have seen in the Democrats’ recent election victories, it seems increasingly clear that to win the vote of swing states requires a vice president who represents the establishment as much as possible. And Walz, thanks to his achievements as Minnesota governor — which include the introduction of laws on gun regulation, protection of gender-affirming care, free school breakfast and lunch for children, the signing of the PRO Act and more — has rightfully earned this position among democratic voters.

As soon as he entered the presidential race, Walz was immediately filed into yet another internet character: the Midwestern dad, the hunter, the football coach, the public school teacher. Thanks to the availability of myriads of pictures of Walz online with kids, holding piglets, on a rollercoaster, with her daughter at the fair (just to name a few) the candidate has been appointed as the “internet dad” via online memes and TikTok videos commenting his overall appearance and much appreciated light-heartedness. After noting the extreme enthusiasm with which the online public greeted the news of Walz’s nomination, Harris’s communications unit immediately moved to forge his new digital alias. Once again, combining some user-generated content with the strategy already applied to the presidential candidate. And so, on Aug. 7, during a rally in Wisconsin, we first saw the indie folk singer Bon Iver wearing a camouflage trucker hat with the surnames “Harris-Walz” embroidered on it. The hat was inspired by the one Tim Walz was wearing when he got the call from Harris asking him to serve on the ticket, but many observers online also noticed that the hat bears “some” resemblance to the “Midwestern Princess” headgear sold by the iconic pop singer Chapell Roan. The hats were sold out just 30 minutes after they were released as the official merch of the democratic campaign, raising nearly $1 million dollars.

It should be said that, with or without memes, Walz comes across naturally as a very joyful person, and joy is something that has been largely missing from all the political actors we have seen on the US political stage in the last decade. After Trump tore up the political scene for nearly nine years, it seemed impossible to reestablish a sense of party affiliation without having to go through the mantra of “saving democracy” from the hands of the Republican tyrant. In the Clinton and Biden campaigns, the focus of their message was too long on Trump, which made voting a moral obligation rather than a gesture of hope for a new society. In this sense, Walz’s strong presence has been able both to lighten the Democratic campaign and to remove visibility from a candidate who — instead of receiving hours and hours of criticism — was simply designated as “weird”. The directness of Walz’s communication style parallels his image: it is not sloppy or plain, but simply essential. A plaid checkered shirt, jokes to his vegetarian daughter, the struggle for middle-class America, sincere disinterest in Trump and JD Vance. And an immense drive to win the election.

Overall, the strategy adopted by Kamala’s HQ allowed the Democratic campaign to react nimbly to change and charm thousands of potentially young disenfranchised voters who feel attracted to a meme factory that automatically excludes older generations from partaking in the creation of a shared niche culture (a notable example of this is represented by Fox News and other media outlets trying to decipher the meaning of “brat” and the various remixes of Kamala’s speeches with Charli xcx’s songs).

One of the reasons why this communicative approach works so well is because Harris and Walz are relatively new candidates within the US political scene, especially to the international public. And new candidates are perfect for memeification, as they serve as blank pages to be filled with the visuals crafted by online users. In this sense, the campaign adopts some of the features of political fandoms, where users decide which aesthetic and which “persona” the candidate represents in their mind, and share them online to see if this generates response by other users. Overall, this allows for a collaborative re-imagination of their roles as characters in the broader political landscape, creating a sense of collectiveness where visuals translate into shared values.

On the other hand, however, the strategy adopted by Harris differs from political fandom because the memeification of the candidates was not entirely spontaneous, but rather controlled and enhanced by the candidate’s communication team, which somehow “forced” the process of visuals-creation. For this reason, the main risk with this branding formula is that Harris could end up looking too needy to get young people’s attention by following the latest TikTok trend. Meaning that, by dragging coconut-themed memes and Walz’s image of the “normal guy” for too long, the overall communication strategy has been probably perceived as if Harris was trying to “mimic” real people online, slipping once again into the cringe valley. And lastly, it is important to notice that the excessive memeification of the candidates might have resulted in a backlash if the two were to run the country, since the extreme simplification of candidates into tropes could easily turn them into memes against them if, for example, they failed to maintain their electoral promises.

The Parable of the Coconut

This “interlude” in the 2024 US election campaign constitutes yet another step forward in the development of the Superstorm, a metaphor which I have used in my first book to describe how the entanglements between new media technologies and political communication shape our understanding of politics. This summer, both Harris and Walz played two internet aliases, respectively the “brat girl” and the “Minnesota princess”, mixed with their “in real life” workhorses, which saw Harris’s narrative as a prosecutor against a felon, and Walz’s as the champion of middle-class American causes. However, the question remains as to whether the diversification of the narratives fielded by the Democratic campaign will be able to “reunify,” in the future, at times of crisis for the party.

It is quite difficult to compare this chapter of political communication history to other case studies because, as I mentioned earlier, it represents a rare historical occurrence, where a candidate found herself planning a campaign in an extremely short time frame. However, I disagree with those who say this factor was ‘fatal’ to the election or to the success of the campaign. On the contrary, I believe that the opportunity to design a communication strategy within five months allowed the candidate to make fewer mistakes and to offer a dynamic, responsive communication system. In order to deliver a successful image, the party needed a strong candidate, not a strong strategy.

On one hand, the campaign Harris set up was a novel element in the history of political communication because it was based on diversifying the candidate’s identity across the online and real-world spheres, creating two personas ready to meet the needs of highly varied demographic segments. At the same time, however, this approach marked one of Harris’s major missteps: the assumption that the online audience (especially younger users) could be ‘swayed’ by trends, resulting in a campaign that, in a way, ‘mocks’ and ‘exploits’ viral trends to create support. Yet, this is unfeasible: inside jokes and virality are unprogrammable phenomena, and collective intelligence cannot be manipulated, even by the most skilled online strategists.

“You think you just fell out of a coconut tree?” recites the famous parable raised by Harris at a White House ceremony in May 2023. In her attempt to craft a multifaceted persona, appealing to both conservative and progressive factions, she failed to realize that no amount of image-shifting could erase her past positions on key issues like border security, the Palestinian conflict, and gun control. And that, neither users — nor voters — have forgotten. Instead, they saw through the contradictions, and in the end, it was Harris who fell from the high branch she had tried so carefully to climb.

Other Worlds is a small, artisanal journal dedicated to design research, criticism and transformation. Its goal is to look at the social, political, cultural and technical complexities surrounding design practices, making them legible and therefore mutable.

OW features articles, interviews, short essays and various other cultural products that don’t fit neither the fast-paced, volatile promotional machine of design media nor the necessarily slow and formal processes of scholarly publishing. This approach allows the journal to address pressing issues without compromising on rigor or depth.

Editorial Board: Silvio Lorusso (editor), Francisco Laranjo, Luís Alegre, Rita Carvalho, Patrícia Cativo, Hugo Barata

More information can be found here.

Other Worlds is currently seeking sponsorship. If you would like to support us, get in touch at s [at] silviolorusso [dot] com.