OW #19: “They Built World: A Boyhood in Graphic Design” by Gilbert

In this issue, Gilbert offers a vivid autofiction of their childhood fascination with graphic design, detailing formative encounters with cult magazines, coveted toys, and niche board games. The journey reflects a gradual immersion into a world of vibrant imagery, compelling typography, and the irresistible allure of the commodity.

Coming Soon I murmured, half-asleep. I was tucked up in my red, grey, and white striped bedsheets, just a boy in the midlands of the provincial English 1980s. Back then, Graphic Design’s big-coloured, bold-faced, drop-shadowed visualities were electric, emitting cultural authoritativeness like a spark-spitting lightsaber and I craved it. From a young age, and quite intuitively, I recognised that marks made by hand, even the most expressive, even the most artful, were feeble affectations compared to the machinic products of Graphic Design. Print culture was at the height of its spectacular powers. At that very moment, as my eyes began unconsciously to open, print salesmen were already coursing though the arterial roads of England, proffering their extravagant swatchbooks of ultra-violet metallics, texturised laminates, and iridescent hot foils; while in the factories blue-overalled press-minders proudly brought their ink densities up to spec. Those presses, they never stopped.

It was my big day. When I came down for breakfast I saw that my mother had already collected my magazine subscription from the newsagent. There must have been a dozen copies of Look-in, my pop-music-culture weekly, presented on the table?! I was puzzled momentarily, until — still that thrill takes me! — I realised that something profound had happened. “It’s on page five,” she said, as I handled one in disbelief. My dear mother had arranged for my name to be printed on the Birthdays page. There I was, Gilbert (9), in the blackest Futura Black, humming magenta background, my name immutably inked amidst an egalitarian list of fellow readers and our famous idols, whose names were highlighted with a star. This unreal proximity, this frisson between the ordinary and the celebrity was the heady promise of the Birthdays page. My mother had successfully negotiated for my passage across its threshold with the editorial staff of Look-in, the arbiters of those gargantuan printing presses hidden from view on some high-security out-of-town industrial estate. I had been admitted to the canon and I felt something.

My childhood sketchbooks were intoxicated by Graphic Design. Before Look-in had sparked my naive infatuation with camp 80s pop styling, mine was a typically boyish imaginary, inhabited by warriors, beasts, and robots. What distinguished my nascent creativity, as I see it now, was that everything I drew did so very willingly corrupt itself with branding, did so obediently fantasise its own commodification. I repeatedly catalogued a brand of monster toys of my own design, the Horror Bugs, whose kind I instinctively knew had to be presented as a product range: organised according to the commercial logics of cross-promotion and accessorising. One well-worked sketchbook page, strewn with sharp-pencil renditions of corporate IP’s© typographic® tokens™ was headed, in carefully-coloured-in bubble-lettering: New! Horror Bugs presents The Dino Bugs. The leader of this prehistoric faction, The Demon-Bug, was shown astride a formidable vehicle. The Horn, I noted with litigious zeal, was sold separately.

Having thus acculturated me to its mainstream desirousness, Graphic Design would coax me further, luring me onward, teasing its arresting insignia of adolescent, male-coded, fantasist pursuits. Look-in was replaced by White Dwarf, a shrine to role-playing board game subculture. My having assented, against my mother’s advice, to this publication’s monthly cadence was in itself evidence of my growing maturity. Anticipation would peak in pangs of desire as I ran panting to the newsagent after school on the very first day on which the new issue could possibly have been delivered. This was a step away from popular print’s eye-catching economies of scale. A step toward the weird, the niche, the specialist. The primary palette of Look-in gave way to modest white pages and black print, colour afforded on the cover only. It didn’t matter. White Dwarf perpetuated another kind of graphic order, its monochrome surfaces arrayed with impossible knots of ornate Space Ranger liveries and grotesquely disfigured Orc heraldry. Only the occasional, crassly sexualised female figures were denuded of significant iconography.

For all its absorbing graphic laboriousness, White Dwarf would instil a doubtful disaffection in my younger self. What if I cannot surmount its imposing barrier to entry? What if I am never beckoned across its threshold of belonging? I had been dutifully collecting the miniature figurines which represented a player’s armies in Warhammer 40K, White Dwarf’s affiliated fantasy gaming franchise. But, however hard I longed to, I had neither the dexterity nor the application to paint my charges as I saw them painted in the magazine’s awe-inspiring dioramas. When White Dwarf went full-colour, a crisis of self-doubt crept up on me. As each successive issue escalated its display of decorated game pieces to wickeder and wickeder levels of intricate technical artistry, a schism took hold between my imaginative escape into those photographic realms and my sorry boxes of naked, leaden figurines, their shameful metallic tang lingering on my fingers.

Nor could Magic the Gathering revive me from this discontent. By age 11 my friends and I were allowed, mercifully, to seek temporary refuge from the obscure outskirts and venture, unsupervised, to our nearest city centre. It was there, one Saturday morning, that first I touched and bought and opened Magic. Special-colour printed, spot-gloss varnished, their rounded corners perfectly die-cut, those cards slid tantalisingly out of their ethereal, weightless wrapper into my expectant clutch. And that saccharine scent! That spirituous vapour of the factory escaping deliciously from its airtight enclosure. I was seduced. Do it to me, Graphic Design. As the penultimate card in my virgin pack revealed its elusive, iridescent aspect my reverie was interrupted by one of the older boys. “You should sleeve that, it’s a foil rare,” they offered, in an uncommon abstinence from sarcasm. I had no concept of it then, but soon scarcity would be all that my friends and I talked about. We speculated longingly about the coveted cards waiting unopened and untouched in the shop, in the three or four shops we had visited on trips with our parents, in the world.

I knew boys who, from first contact, were utterly consumed by Magic’s endless spiral of reprints, supplemental booster-boxes, and its deck-building, card-trading secondary market. Not me. That first precious rare which I had pulled depicted a young wizard atop a shimmering ground of rainbow foil, energetically poised to cast a spell. They looked barely older than I was. And they weren’t, in fact. I learned that such special cards bore the likenesses of real-life Magic champions, whose tournament victories entitled them to enter the mythical realm of the game’s Graphic Design, and to contribute their lore to its arcane rulebook. Another unfathomably high bar. And so it was that, as on every Magic card, beneath the young wizard’s image was a field of text accounting for the card’s in-game functions. My peers took pleasure in slavishly memorising and reciting, word-for-word, these mandates. The pedantic officiousness that Magic inspired in them repelled me.

When next I transgressed Graphic Design’s threshold it would be for good. The defining aesthetic experience of my life. My mother had saved money to buy us a PC, whether on the promise of entertainment or education I cannot recall. I bought games for it on cassette tapes packaged in plastic cases: not the clear kind in which music was sold, these were opaque black with a clear film bonded to the outside, into which the printed game art was inserted. By word of the school playground’s mouth, I was drawn to the title R-Type. It would have me pilot a lone fighter ship into the dark, outer reaches of screen space, casting me as humanity’s last hold-out against the encroaching alien Bydo race. It will never be possible to communicate, to the generations which came after ours, how we revered the animated graphics of those early home computers. How fully they accomplished our suspension of disbelief. In the progression from ZX Spectrum to Amstrad CPC to Commodore Amiga, we greeted each minor improvement in graphical sophistication as if it marked, definitively this time, the ultimate transition into pure virtual immersion, absolute realism, total believability. All along, of course, it was us, our becoming ever more able to project visions onto those simplistic 8- and 16-bit displays.

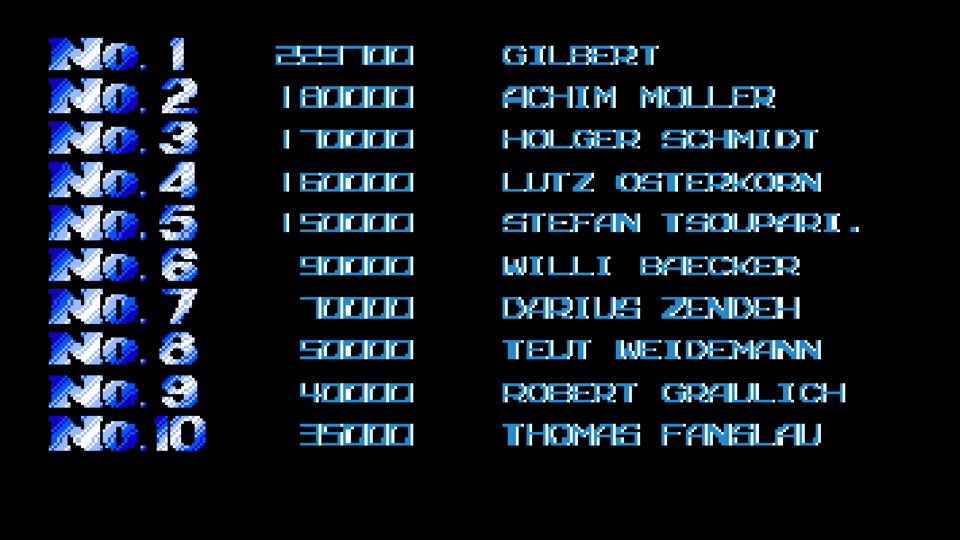

Eventually I progressed far enough into my fraught mission to rank on the R-Type high scores screen. I was presented there with a sight of unforgettable typographic allure. Remember: there was no network then, no forum where other players would gloatingly compare themselves to my modest achievements. No, these round-number high scores had been contrived to situate the player in their progression through the game, each score credited to one of the game developers themselves. The look of those glyphs though! The letters and numbers were stylised to glimmer with the sensory pin-prick of a laser beam refracting over the hull of my vessel, my R-9 Arrowhead, as I had heroically piloted it, surging so perilously through space into enemy territory, and… As I typed my name, G I L B, the letters — these letters, my letters! — were rendered immediately on-screen in that scintillating font. Each stroke formed of two sculpted metallic blue pixels, set-off by a one-pixel bright sparkling-white bevelled outline. I backspaced, and realised – in an unfinished moment that will forever open onto insatiable possibility – that whatever I typed, whomever I deigned to be, would be represented there, imbued with that typographic lustre. I was inside. Over the threshold. Inside Graphic Design. Granted agency to command it, there — right there — from my childhood bedroom.

Other Worlds is a shapeshifting journal for design research, criticism and transformation. Other Worlds (OW) aims at making the social, political, cultural and technical complexities surrounding design practices legible and, thus, mutable.

OW hosts articles, interviews, short essays and all the cultural production that doesn’t fit neither the fast-paced, volatile design media promotional machine nor the necessarily slow and lengthy process of scholarly publishing. In this way, we hope to address urgent issues, without sacrificing rigour and depth.

OW is maintained by the Center for Other Worlds (COW), at Lusófona University, Portugal. COW focuses on the development of perspectives that aren’t dominant nor imposed by the design discipline, through criticism, speculation and collaboration with various disciplines such as curating, architecture, visual arts, ecology and political theory, having in design an unifying element but rejecting hierarchies between them.

Editorial Board: Silvio Lorusso (editor), Francisco Laranjo, Luís Alegre, Rita Carvalho, Patrícia Cativo, Hugo Barata

More information can be found here.