OW #17: “Useful Overdrive: On the Usefulness of Chindōgu” by Ana Margarida São Miguel & Madalena Mourinha

In this issue, Ana Margarida São Miguel and Madalena Mourinha, both currently studying at DELLI, explore the Chindōgu movement, highlighting how its whimsical inventions challenge the traditional notions of usefulness in design. They discuss how Chindōgu’s playful yet impractical gadgets question our understanding of utility within consumer culture, and advocate for a broader understanding of design that embraces both the useful and the un-useless.

Why does a pair of house slippers with a miniature dustpan and broom attached to each sole exist? Who would need them? Who would be into them, at least as idea? In other words, where do they fit in our social context and imagination? To answer these questions, we need to analyze and reconsider the notion – foundational to the design practice – of the “useful” (versus the “useless”).

As a field of theory and practice, design has its genesis in the Industrial Revolution and later develops into the multidisciplinary endeavor we know today, an endeavor that affects all aspects of everyday life through artifacts that are fundamentally conceived to be useful. The idea of usefulness, however, has been challenged in various contexts and across different cultures. So, today design no longer follows a “magic formula” rooted in a absolute idea of utility and function. On the contrary, new doors suddenly open to different ways of speculating about what design can be. This is how a space is created where contrasting forces shape, refine, and occupy this fluid structure we call design by discussing issues of execution and applicability across various dimensions. Here, even uselessness can acquire a positive value. As Søren Rosenbak puts it: “Useless design [is] the island that exists beyond your map”.

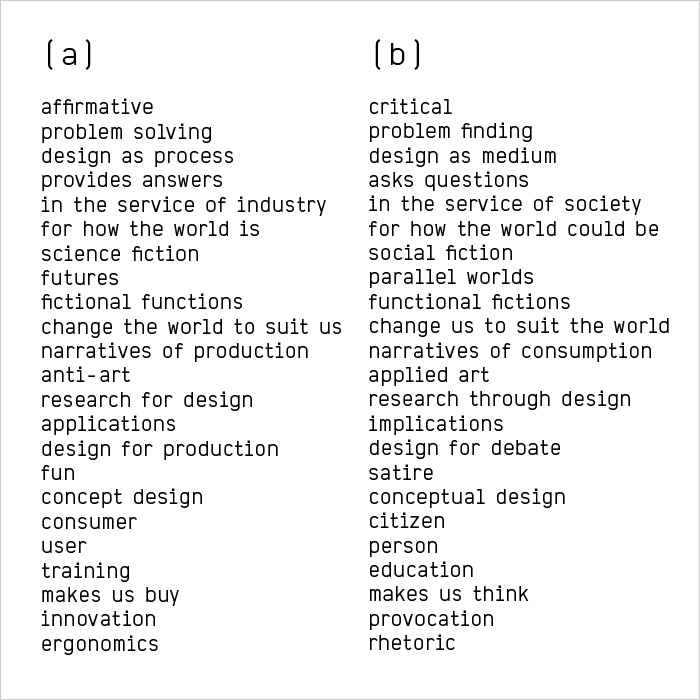

When speaking of design, the attributes most used to define usefulness align with purpose, motivation and intent. These notions are rooted in the Modernist Movement. However, the dualism useful/useless is in reality as ambiguous as that of meaningful/meaningless or critical/conformist – in fact, usefulness might simply conceal our idea of what is critical and therefore meaningful. A “useless” object could’ve once been useful or boycotted by the very same brand that brought it to the store shelves only to be replaced by a “brand new epitome of modernity and technological advancement”. This is what we call “planned obsolescence”, a term coined by industrial designer Brook Stevens. What does that say about us? We have a pseudo-faith in a distant future where tech saves us by changing the way we live. The phenomenon of planned obsolescence murks the waters of our understanding of usefulness. In the A/B Manifesto by Dunne & Raby (2009), we see, in a succinct two column structure, a set of ideas relating to design in antithesis with each other, where (A) displays the conformist, consumption-obsessed society and (B) its opposite. The manifesto illustrates the possibility of the useful and the useless sharing the same house, like flatmates.

To get a glimpse of what happens when the useful and the useless coexist we need to travel east. Japan is home to highly regarded artisanal manufacturing and modern, clean-cut, minimalist design. However, it also showcases a contrasting abundance in its streets: from solitary vending machines to entire towns dedicated to stores selling an incredible variety of items you never knew you wanted, covering every possible franchise. Amidst these extremes lies the anarchic thirst for rebellion of the Chindōgu movement, consisting in creating clever gadgets that appear to be perfect – albeit a bit absurd – solutions to extremely specific everyday problems but often end up causing more trouble than they solve. Like similar movements such as Wabi-Sabi and Mingei, the core principles of Chindōgu are about artifacts made by common people who accept imperfection, impermanence and incompleteness. Chindōgu removes the artist from their pedestal and brings them down from their “high art” status, placing them to the level of anonymous creator. After Kawakami became editor of the popular home shopping magazine Tsuhan Seikatsu in the 1980s and began displaying an array of bizarre product prototypes, Chindōgu was born.

Meaning “odd” or “distorted tool”, Chindōgu aims to create solutions for making life easier. Much like historical inventions, which often leave a trail of failures in their wake, Chindōgu embraces these “duds”. For Chindōguists, this is a goldmine. They abandon any solution that works properly in favor of an almost useful, yet successful contraption. Despite their appearance, Chindōgu items are not made with comedic purpose. They exist in the realm of really specific things we could, at first glance, believe we actually want. But the more we analyze these things, the more the magic is undone, producing a laugh that originates from the paradoxical aspect of failure. This is how these objects display their un-useless quality.

Chindōgu has ten tenets, summarized here:

- A chindōgu cannot be for real use

- A chindōgu must exist

- Inherent in every chindōgu is the spirit of anarchy

- Chindōgu are tools for everyday life

- Chindōgu are not for sale

- Humor must not be the sole reason for creating a chindōgu

- Chindōgu is not propaganda

- Chindōgu are never taboo

- Chindōgu cannot be patented

- Chindōgu are without prejudice

In essence, chindōgu represents a certain freedom to act, while simultaneously making fun of consumer culture. It ultimately takes advantage of the space between usefulness and uselessness, using it as a playground for absurdist and surreal creation.

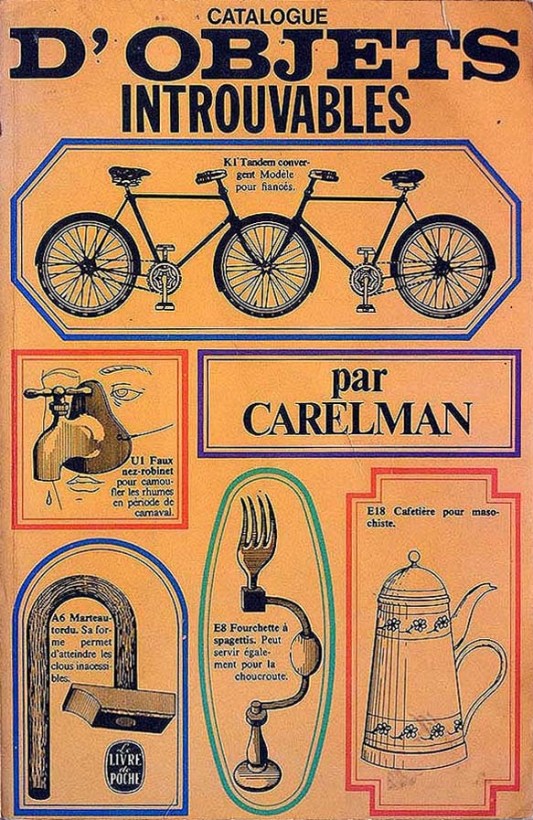

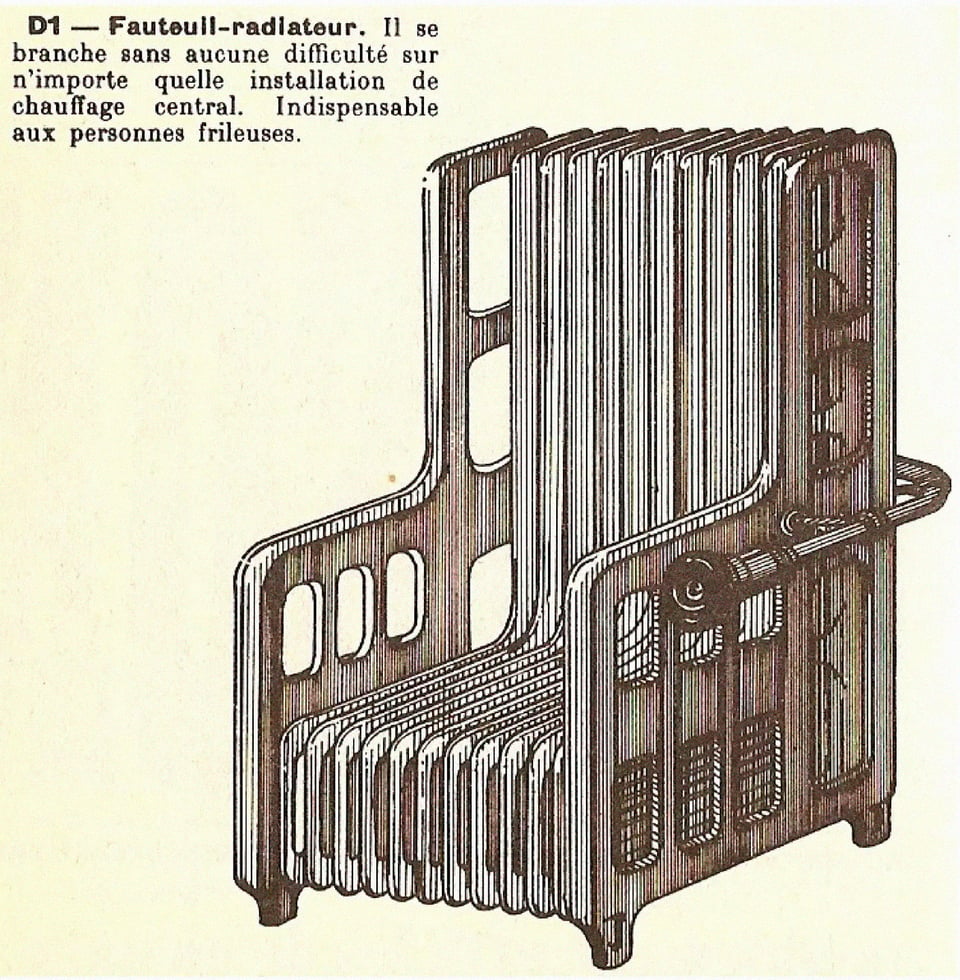

In the same decade, on the other side of the world, French artist Jacques Carelman gathered the Catalog of Unfindable Objects (1984), a two volume book with dozens of illustrations and photographs akin to what we could call “useful overdrive”. A more recent example of the ongoing relevance of this approach is the work of designer Katerina Kamprani. Her series The Uncomfortable includes 3D models and prototypes of everyday objects designed to be dysfunctional, and guided by both architectural and personal influences.

Where Japanese culture tends to be interpreted through a lens of stereotypes and false assumptions, works like Kamprani’s can appear to the untrained eye as just one more funny Flying Tiger gadget. In this sense, there is a risk for these inventions to reach the public without any context attached to them. A selection of Chindōgu replicas and works stolen from Carelman’s catalog already exist, produced by big companies. This commodification defeats the purpose and values of this delicate art form, quickly turning it into a cheap spectacle.After all, why would we need dustpan and broom-equipped slippers? or two beverage mugs intertwined by the handles? or miniature umbrellas for the feet? Because design thinking does not concern itself only with what is needed for technological advancement or economical concerns; it is a playground, a gym for the mind, something that defies what we think we know about common notions such as usefulness, uselessness or even un-uselessness. Reconsidering these values allows us to deepen our understanding of society. The un-uselessness of Chindōgu urges us to ask some difficult general questions: what does it mean for something to be useful? useful for whom? when?

Other Worlds is a shapeshifting journal for design research, criticism and transformation. Other Worlds (OW) aims at making the social, political, cultural and technical complexities surrounding design practices legible and, thus, mutable.

OW hosts articles, interviews, short essays and all the cultural production that doesn’t fit neither the fast-paced, volatile design media promotional machine nor the necessarily slow and lengthy process of scholarly publishing. In this way, we hope to address urgent issues, without sacrificing rigor and depth.

OW is maintained by the Center for Other Worlds (COW), at Lusófona University, Portugal. COW focuses on the development of perspectives that aren’t dominant nor imposed by the design discipline, through criticism, speculation and collaboration with various disciplines such as curating, architecture, visual arts, ecology and political theory, having in design an unifying element but rejecting hierarchies between them.

Editorial Board: Silvio Lorusso (editor), Francisco Laranjo, Bianca Elzenbaumer, Luís Alegre, Rita Carvalho, Patrícia Cativo, Hugo Barata

More information can be found here.