OW #13: “God Save Alegria: On Détournement” by Ana Henriques

In this issue, Ana Henriques delves into the various uses of détournement, a cultural technique developed by Guy Debord and the Situationists to hijack the meaning of images produced under capitalism. A versatile instrument, détournement has been employed in many different contexts, such as the punk movement and the fight against AIDS. Nowadays, the legacy of détournement lives in images that criticise the cosy, pacific illustration style of Big Tech: Alegria.

Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle was not simply a descriptive work; it was also a manifesto. Debord sought to encourage us to not just recognize the spectacle, and how society had, ostensibly, fallen under its spell, but also to attempt to subvert it. He was, in fact, part of a group of social revolutionaries called the Situationist International (henceforth referred to as SI), whose aim was to offer a more modern and comprehensive critique of mid-20th century advanced capitalism.1

The spectacle was a central aspect of situationist theory. The idea of the spectacle was that the history of social life may be understood as a reduction of being into having, and then of having into merely appearing; at which point commodities complete their colonization of social life. Indeed, in the founding manifesto of the SI, Debord describes the established culture as a sort of rigged game, in which conservative powers halt subversive thinking from accessing public discourse. He explains that such thinking is first trivialized, and thus rendered sterile, so that it may safely be incorporated back into mainstream society, where it can be exploited. Though first mentioned by the SI, this process came to be referred to in political theory as recuperation. Its counter-technique, however, is what the SI and Debord described as détournement.2

French for rerouting/hijacking, détournement is, briefly put, the practice of subverting the images produced under capitalism, thereby turning them against it. It is, as Debord states, “the flexible language of anti-ideology,” and, because of that, “[it] has grounded its cause on nothing but its own truth as present critique”. The SI’s advocacy of this technique was based on the assertion that, due to advancements in the domain of their production, all known means of expression will converge in a general movement of propaganda through spectacle, which necessarily encompasses all the perpetually interacting aspects of social reality. This translates into the belief that culture itself was in a state of tilt and that, through détournement, the creation of new expressions and meanings out of already existing works was a radical and preferable means of generating disruption.

In A User’s Guide to Détournement, the situationists argue that the technique has a double purpose. It must, at the same time, negate the ideological condition of artistic production – namely, the fact that all artworks are, ultimately, commodities – and negate this negation by producing something that is politically edifying. A quintessential example of this is the punk movement and its accompanying aesthetic.3

Punk’s purposely provocative style is not inane; it’s an ambitious attempt to signal intentional gestures of rebellion. “In the best of circumstances, punk aims to be a wake-up call to a public otherwise anesthetized by the suffocating conformity of daily existence.” Indeed, according to Curran Nault, following in that same tradition, the political roots of the punk movement can be traced directly to the SI’s philosophy. The punk value system prioritizes non-conformity and individual freedom, as well as opposition to authority and capitalism. And the punk aesthetic does not stray from these values. Punk products were intentionally fashioned to be mostly inaccessible to a mainstream audience. This was accomplished, for example, by deliberate incoherence, a DIY ethos, or the use of wittingly disturbing graphic imagery of a violent or sexual nature. It is by limiting commercial viability that the punk aesthetic attempted to undercut the capitalist imperative of profitable work and consumption.

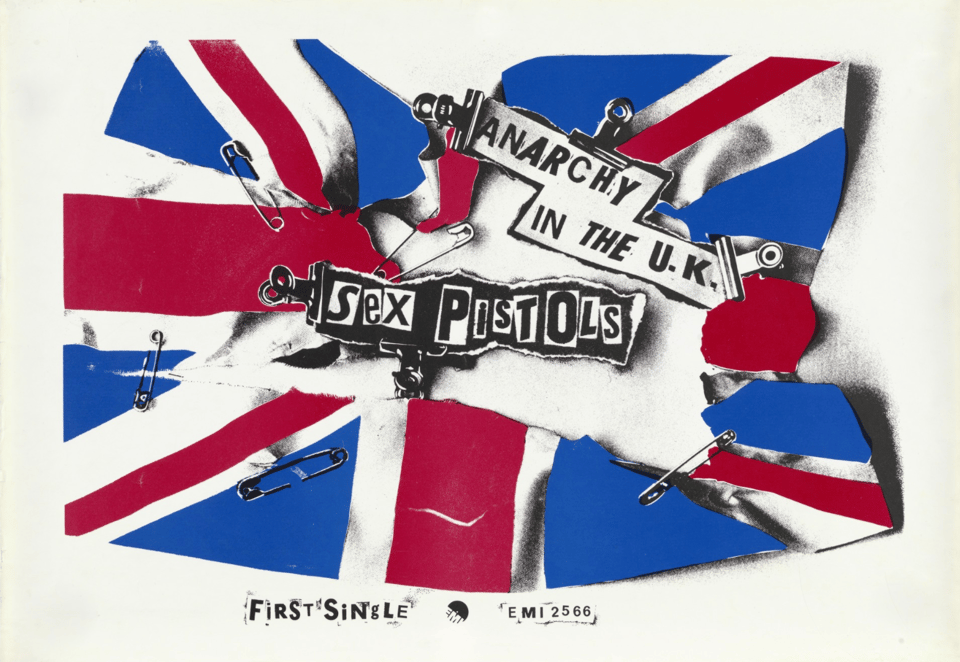

“[A]rguably punk’s most important artist,” Jamie Reid is most well-known for helming the art direction for the iconic punk band the Sex Pistols – so named to evoke the aforementioned sex and violence cornerstones of the punk aesthetic. Reid, as a figurehead of the punk movement, also drew heavily from situationist philosophy, with détournement being very prominent in his work.

Jamie Reid, 1976, “Anarchy Flag” single cover.

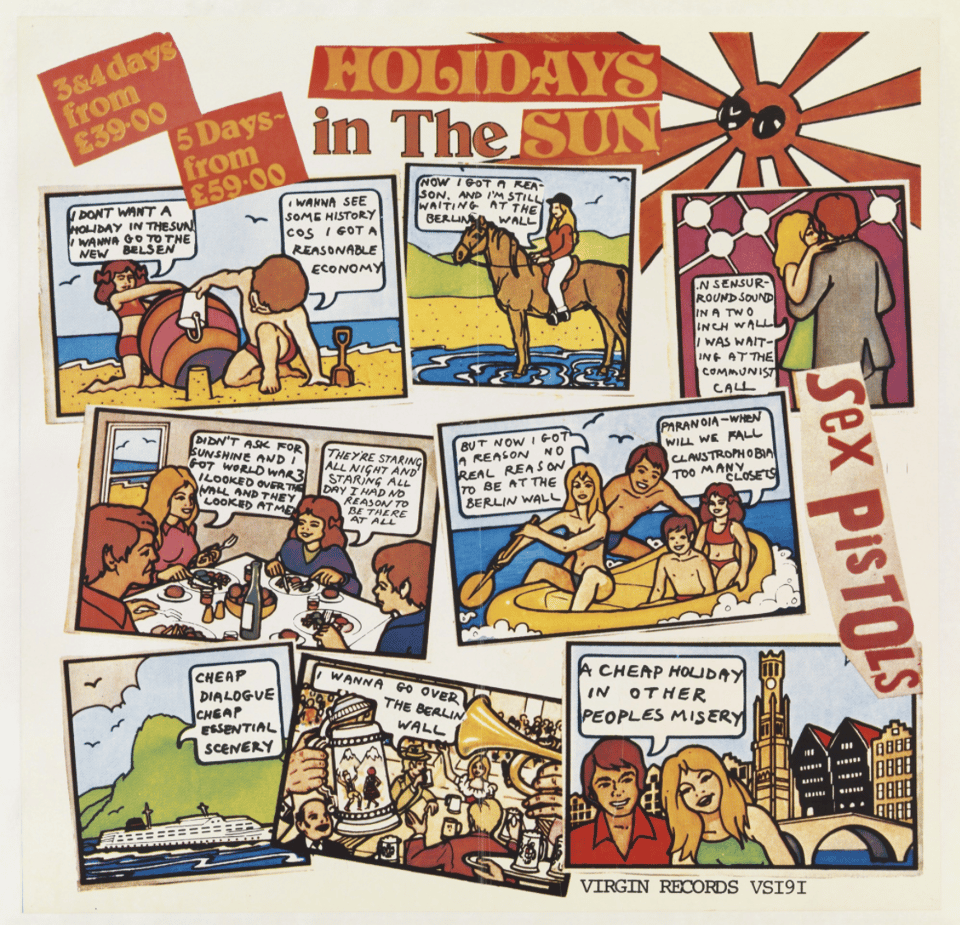

Jamie Reid, 1977, “Holidays in the Sun” single cover.

In Anarchy Flag, we see a ripped and burnt Union flag, reassembled with safety pins. Upon the tattered flag also lie, affixed with clips, the band’s logo and the title of the single. The use of a flag, typically a national symbol of pride, here, was meant to quite literally deconstruct what that pride meant. By destroying that symbol, Reid intended to transform its original meaning into one of dissatisfaction and pent-up rage at the status quo. The band logo itself is also interesting, in that it evokes the imagery of a torn ransom note, again alluding to the violence and DIY aesthetics that were so characteristic of the punk movement.

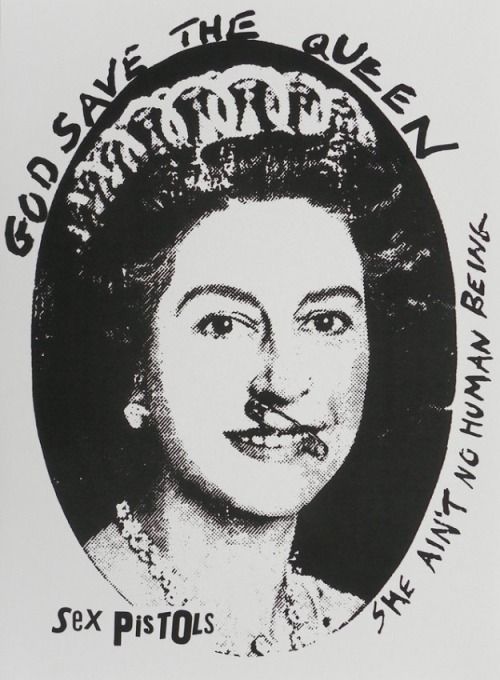

Jamie Reid, 1977, Alternate “God Save the Queen” artwork.

The artwork for the God Save the Queen single was an appropriation of an official portrait of a smiling Queen Elizabeth, taken by Cecil Beaton. The single itself was intended to coincide with the Silver Jubilee of the queen. The cover art had many variations, but the original featured the queen’s portrait upon an image of the flag, her eyes and mouth covered by the band’s logo and song title. Another version depicted the queen’s image with a safety pin across her lips alongside a lyric from the single written in what appeared to be marker: “God save the queen she ain’t no human being.” Another still depicted the same image but the queen’s eyes were replaced with swastikas. According to Reid himself, “[t]he flag poster was another adaptation of the idea already used in the ‘Anarchy’ campaign: that there was another England not mentioned in the worldwide media coverage of the Jubilee Jamboree.”

The Holiday in the Sun cover art, maybe my personal favourite of these examples, was a direct reference to the poster work of the SI. Reid used an actual Belgian Travel Service brochure, which depicted tourists engaging in all sorts of fun, leisurely activities, as a template to build on top of. He replaced the original content of the speech bubbles with lyrics from the single, which referenced a Nazi concentration camp, the Berlin Wall, and Communism, culminating with the cry “a cheap holiday in other people’s misery.” This last verse was itself a reference to a situationist graffiti which read “Club Med – A Holiday in Other People’s Misery.”

All three of these examples aptly illustrate the practice of détournement, especially how it uses known visual and textual references to make a political statement. And these statements can spread widely. In fact, the punk movement was so successful that it can be directly traced to a resurgence of the feminist movement. The “second wave” of feminism, which began around the same time, that is, in the 1970s, was heavily inspired by the punk ethos, and their marriage spawned such subcultural phenomena as the Riot Grrrl movement. The latter is itself tied directly to the “third wave” of feminism, a key figure of which was Kathleen Hannah, former singer and guitarist of the Riot Grrrl band Bikini Kill.

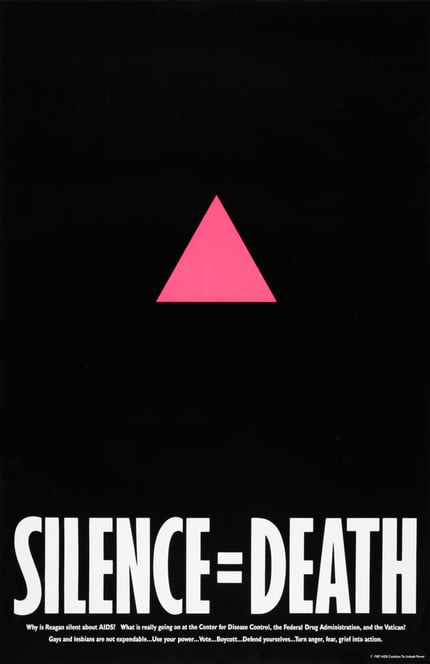

We now see that détournement can, and indeed has been, directly linked to important cultural shifts. Détournement is rebellious. It is using the pink triangle as a symbol of resistance to HIV/AIDS after it was used to mark those deemed “sexual deviants” by the Nazis in internment camps.4 It is a Sonic the Hedgehog meme which uses a capitalist creation to denounce capitalist complicity. ACT UP’s Silence = Death poster and Sonic’s slogan are both powerful and enduring examples in our collective consciousness. It is under the lens of détournement, particularly as a tactic of counter-cultural intervention, that we might truly begin to understand why. Indeed, these images all caused shifts in meaning by simultaneously generating both the recreation and the negation of previously held signs and significations to make important political points. They were culturally significant because people understood the language in which they were communicating, and thus understood the points they were making much more effectively.

Unknown artist, n.d., There is no such thing as ethical consumption under capitalism meme.

ACT UP’s Silence = Death poster, 1987.

Perhaps my favourite contemporary example of détournement is a parody of Francisco Goya’s famous Saturn Devouring His Son painting done in the Alegria art illustration style. If you haven’t heard of Alegria, you have certainly seen it. Also called Corporate Memphis, big tech art, flat art, globohomo art, etc., it has become somewhat ubiquitous, especially in tech branding. It is an upbeat Matisse-esque style of illustration which depicts generic people, often with non-skin-coloured skin and wacky proportions, doing fun things. You know the one. It’s everywhere, from Facebook to Slack to Airbnb.

Francisco Goya, 1820-1823, Saturn Devouring His Son, located in the Museo del Prado.

These amorphous and unrealistic characters are so because, in representing no one, they can represent everyone. This is especially useful to corporations trying to have mass appeal. They are ethnically non-specific to represent a vague promise of diversity and, to avoid privileging any body type over another, they have a cartoonish one. They are designed to convey expressiveness – Alegria being both Portuguese and Spanish for joy – rather than individual identity or any actual commitment to substantive representation. I find the dissonance between the typical cheerful depictions done in this style and the gruesome imagery of the Goya painting amusing, to be sure; however, the core reason why I personally enjoy it goes deeper than that.

@clayohr, 2021, Parody of Saturn Devouring His Son. Image kindly provided by the artist.

Saturn Devouring His Son depicts the Greco-roman myth of Saturn and Jupiter (or Kronos and Zeus, if you’re more familiar with the Greek version). As the story goes, it had been prophesied to Saturn that one of his sons would dethrone him. And so, as one does, fearing that he would be overthrown, Saturn ate each one upon their birth. Jupiter, nonetheless, survived, and later did indeed dethrone the titan. I find this context really interesting in regard to the parody, especially when considering it as an example of détournement.

The symbolism of Saturn being defeated by his own progeny is paralleled by the technique itself, which is capitalist-bred imagery being used as an act against capitalism – much like the Sonic meme. Furthermore, Goya himself was grappling with the concept of power at the time of painting. Namely, how the powerful treat their own in order to remain in power. This, I find, makes his depiction of Saturn’s act a particularly apt one. Look at the desperation in Saturn’s bulging eyes. This is an act of desperate self-preservation. When you look in the eyes of the illustrated parody, all you see is indifference. This is not a desperate act of self-preservation; it’s a midnight snack. Seen under the transgressive light of détournement, this work shows its most searing and powerful critique – that the capitalist enterprise is just as cruel, while remaining indifferent to human suffering.

This text is a slightly edited excerpt of Ana Henriques's first book entitled Designing Futures: How Can Ethics Shape Design Theory and Practice. The book can be downloaded for free here.

References

Beramendi, P., Häusermann, S., Kitschelt, H. and Kriesi, H. (eds.), 2015. The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Briziarelli, M. and Armano, E., 2017. “Introduction: From the Notion of Spectacle to Spectacle 2.0: The Dialectic of Capitalist Mediations”. In Briziarelli M. and Armano E. (eds.), The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism. London: University of Westminster Press, pp. 15–48.

Bird, G., 2011. How France gave punk rock its meaning. [online] BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-12611484 [Accessed 24 February 2021].

Debord, G., [1967] 2004. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by K. Knabb. London: Rebel Press.

Debord, G. and Wolman, G., 1956. “A User’s Guide to Détournement”. In Les Lèvres Nues, #8.

Genchi, C., 2017. “A Possible Herstory”. In Guerra, P. and Moreira, T. (eds.), Keep it Simple, Make it Fast!. Porto: Universidade do Porto. Faculdade de Letras.

Harris, B. and Zucker, S., 2015. Francisco Goya, Saturn Devouring One Of His Sons. [online] Smarthistory. Available at: https://smarthistory.org/goya-saturn-devouring-one-of-his-sons/ [Accessed 22 February 2021].

Marcus, G., 1989. Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nault, C., 2018. Queercore: Queer Punk Media Subculture. New York, NY: Routledge

Plant, R., 1986. The Pink Triangle: The Nazi War Against Homosexuals. New York, NY: Holt Paperbacks.

Plant, S., 1992. The Most Radical Gesture. New York, NY: Routledge

Reid, J. and Savage, J., 1987. Up They Rise! The Incomplete Works of Jamie Reid. London: Faber.

Rogers, A., 2006. The Influence of Guy Debord and the Situationist International on Punk Rock Art of the 1970s. MA. University of Cincinnati.

Teurlings, J., 2017. “Society of the Spectacle”. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects.

Other Worlds is a shapeshifting journal for design research, criticism and transformation. Other Worlds (OW) aims at making the social, political, cultural and technical complexities surrounding design practices legible and, thus, mutable.

OW hosts articles, interviews, short essays and all the cultural production that doesn’t fit neither the fast-paced, volatile design media promotional machine nor the necessarily slow and lengthy process of scholarly publishing. In this way, we hope to address urgent issues, without sacrificing rigour and depth.

OW is maintained by the Center for Other Worlds (COW), at Lusófona University, Portugal. COW focuses on the development of perspectives that aren’t dominant nor imposed by the design discipline, through criticism, speculation and collaboration with various disciplines such as curating, architecture, visual arts, ecology and political theory, having in design an unifying element but rejecting hierarchies between them.

Editorial Board: Silvio Lorusso (editor), Francisco Laranjo, Bianca Elzenbaumer, Luís Alegre, Rita Carvalho, Patrícia Cativo, Hugo Barata

More information can be found here.

-

In political philosophy, with special focus on the Frankfurt School of critical theory, the term “advanced capitalism” is used in social contexts where a capitalist model has been thoroughly consolidated and developed due to its endurance for an extended period of time. ↩

-

This technique was developed first by the Letterist International, of which Debord was a founding member. The group later went on to form the Situationist International, among other initiatives. ↩

-

Interestingly, despite how influential their work was on the movement, Debord and the Situationists disliked the punks. Beyond not enjoying the “noise,” they felt the punks were too focused on the individual and not enough on the collective – a core pillar of the situationist critique of the spectacle, as mentioned earlier. The situationists critiqued the punks for not engaging in concerted collective efforts to actually erode capitalism, accusing them of a shallow kind of opposition, which they argued could be easily commodified. ↩

-

Prisoners marked with the pink triangle were mostly gay and bisexual men, as well as transgender women and other AMAB individuals. Lesbian and bisexual cisgender women, trans men and other AFAB people were not systematically imprisoned in the same way, mostly because a supposed female sexuality was not considered at all. Those that were, however, were classified as “asocial” and made to wear a black triangle. ↩