What the Cambrian Explosion tells me about 8-bit video games and Tim Burton’s napkin sketches

2025-02-07

About two hundred and something million years ago, myriad forms appeared in the fossil record. Before animal life ventured out of the ocean to set in motion the dominion of big hefty reptiles and planet destroying apes, nature seemed to have a bit of a "think outside the box" ideas session. Animal forms and body designs that were never been seen since populated the oceans.

Who knows why the vertebrates, molluscs and plants won out as far as legacy is concerned and whether it was sheer bad luck for the evolutionary dead ends that all those other forms ended up being? A few aeons after that, the big stomping lizards got wiped out by an asteroid and a small subset of experimental flying dinosaurs managed to scrape by. Meanwhile, some small, furry critters that were really good at running away and hiding whenever shit got real managed to ensconce themselves into enough subterranean crags to weather that apocalypse so that the same spirit of experimentation could once take off. Furballs of all varieties populated the land, sea and air until a combination of climate change and the rise of a particularly clever furless furball consigned the poor giant round sloths, sabre tooth cats and mammoths to oblivion.

So, while many make a big thing about the Cambrian Explosion as evidence of nature and evolution at its most creative, this wasn’t entirely true. Whenever the board was wiped clean by a cataclysmic event, life became creative again, spinning multiple new forms from whatever was available to work with at the time.

Similar things can be said about culture, creativity and art. The silent era of cinema is popularly associated with slapstick comedy but it's also an era that is ripe with experimentation. Part of this was in response to the new technology of celluloid and the moving image, but this also took inspiration from Modernism and the exploration of what the still image could be after photography heralded a death knell for painterly realism and representationalism.

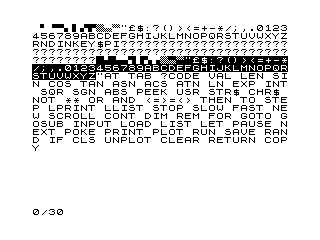

I consider myself to be lucky that I was of an age to witness the first years of video games as a form of home entertainment. This was the 8-bit era where many of the blueprints were hatched for what a game could be as a two dimensional interactive entertainment. This included the first time you could write (or copy out) code in the early computer language of BASIC into a home computer and run it. These lines of punctuated jargon and numbers meant very little to me, but if you had entered them accurately then you would be able to run it as a very basic game. I'm glad I had that experience of the digital alchemy of coding – how characters typed out on a rubber keyboard could transmute into moving, reactive entities on a cathode ray screen.

I have previously written about the primal perfection of Super Mario Brothers but the slick and snappy Japanese platformers of Sega and Nintendo weren't really a part of my childhood. Our household was lorded over by the janky idiosyncrasies of the European home computer. We owned a ZX81, a Spectrum and an Amstrad PC for most of the 80s before the arrival of a Gameboy and a Sega Megadrive (or Genesis if you're weird) in the early 90s.

The 16-bit era added polish and finesse to what had come before but it was the 8-bit era that threw everything at the wall – an explosion of design that resulted in many of the genres that are still going strong today. On top of that, there were a multitude of curious evolutionary dead ends. Perhaps it was because Spectrum games used audio tapes rather than cartridges that there seemed to be more games released and by that token more miserable (yet glorious) failures. Even when genres such as the text adventure fell out of favour with gamers, their devs would still keep at it, often mailing games to buyers from their home addresses when they could no longer get them onto retailer shelves.

I mention this time because I want to explore how mega budget video games seemed to deal with their own extinction events in 2024 while there seemed to be a return to those primal 8-bit origins. While a certain David/Goliath mentality might be evoked to celebrate the fall of titans and the rise of the plucky indie upstarts – it should still be remembered that these commercial failures resulted in studio closures and mass layoffs. The CEOs kept their grip on the high life and continued to fail upwards while the workers took the brunt of the impact.

Still, it's interesting to see the upstart winners of the year came from small teams or from single developers. The big Indie game of 2024 was of course, Balatro, the chaotic poker game with its array of glitchy jokers making sure that no single play through was the same. I became quite addicted to it twice, once when it came out on Steam and again when it was ported to iPad. On both occasions I had to delete it from my devices but it inspired an essay about Ballatro and Allen Ginsberg's ideas about the perils of a world of pure imagery.

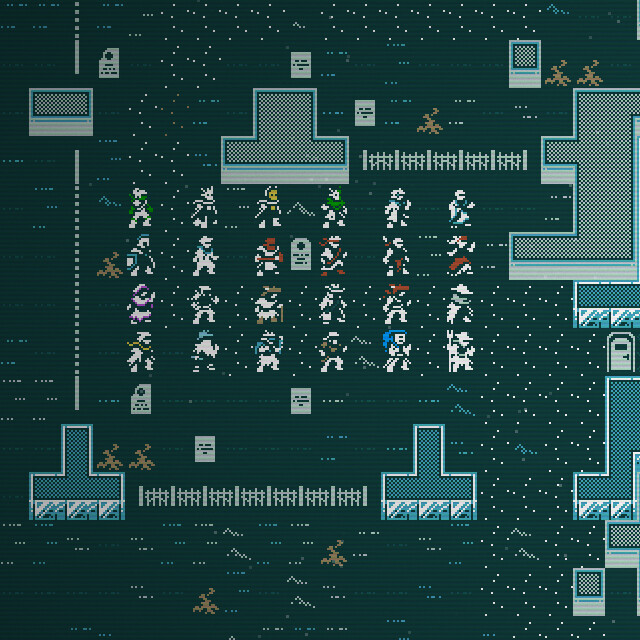

Two more Indie games caught my eye this year, both of them sharing aesthetic and genre-related connections with the games of the 8 bit era. Caves of Qud is decidedly old school with its sparse pixelated graphics (upgraded from the ASCII graphics of the earliest versions) representing a rich, expansive open world and the sentient entires that populate it (I say "sentient entities" because this is a game where your main character can became a door). The simplicity of the graphics belie the complexity of the game's mechanics. Procedural generation and deep simulations allow for increasingly absurd situations and often comical death. I have barely spent a couple of hours within the game but my most recent death came as a result of my character trying to kill a skunk for some much-needed food and the skunk turning out to be a supremely powerful being that was able to change the atmospheric pressure around my character's body and crush it.

Another new game that I have barely scratched the surface of (despite notching up 20 hours of playtime) is UFO 50, an anthology of 50 games from a fictional game publisher that operated throughout an alternative 80s timeline. These games begin at the dawn of 8-bit gaming and work their way up to the beginning of the 16-bit era.

Again, I have barely scratched the surface, spending most of my time in Magic Garden (a game whose design echos the micro-computer and Nokia mainstay, Snake). Another game, Mortol, involves navigating your way across levels, killing off your limited supply of characters in order to create platforms, stepping stones or set off buttons that drain bodies of water and kill the chomping beasties that live within them.

There's a certain resistance that a player night feel on browsing through these games after playing a slick, realistic, megabudget game. But one thing about the games of UFO 50 is that, inevitably, one of them will eventually pull the player in – often a game that is significantly different in its design and philosophy to the genres and standards that dominate gaming today. Part of that pull is due to that primal, Cambrian energy – a return to gaming's origins where those myriad forms sprung into existence to take their stab at defining what a video game could be.

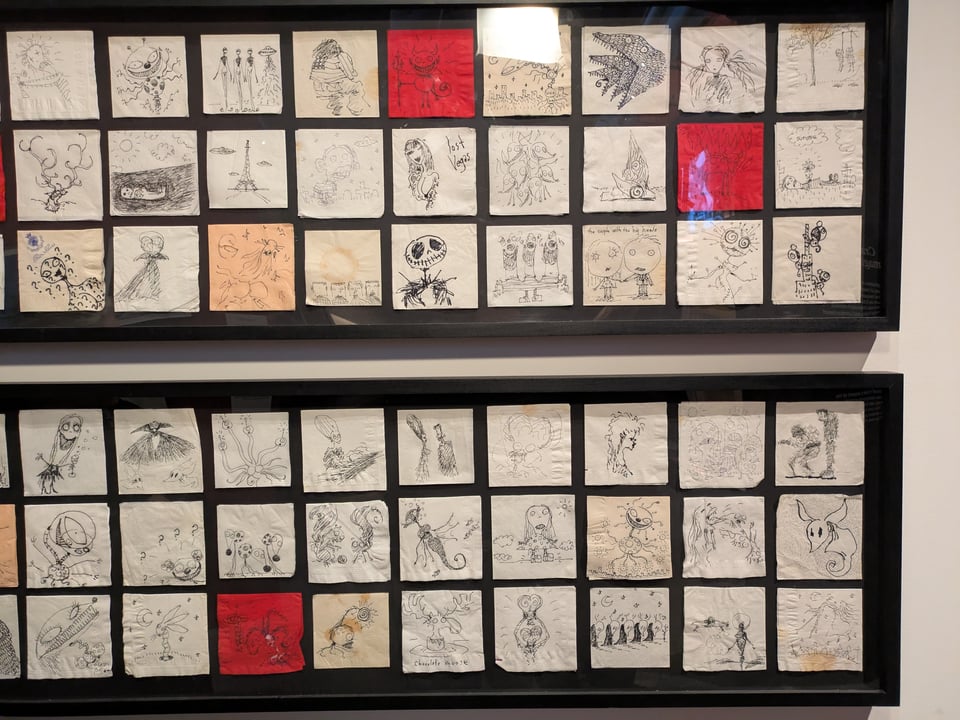

Of course, this sense of wiping the slate clean and starting again doesn’t just apply to video games. At the end of 2024, Mrs O’Sullivan treated me to a visit to the Tim Burton exhibition at the Design Museum. While it was great to see the original figures from Nightmare Before Christmas as well as the Catwoman costume from Batman Returns, the exhibit that had the most profound effect on me was a display case of napkins that Burton had sketched on.

What's so special about a napkin? I think it comes from how there are no expectations with a napkin, it exists to wipe a face clean before being balled up and chucked. The blank page – be it a sheet of paper on a desk or a white rectangle on a laptop screen – is a space that is heavy with the expectations and aspirations of the artist or writer. From a writer's perspective, it is already a literary object. The napkin, on the other hand, is simply trash in its larval state. There is no pressure. It is an invitation for the artist to fail. It is a medium that is more forgiving of failure, it is also closer to that same state of primal creativity that the game dev finds when they forsake the latest game engine for something that harkens back to the 8-bit era.

This is the reason why I prefer to write in longhand or with a basic text editor rather them using something like Microsoft Word. Not only do those tools help to simplify the act of writing, they also help me to get back to how things were when I fell in love with writing in the first place. No matter where you are with your practice, it's always helpful to take a big step backwards – to remind yourself why you do this this, to get tack to that sense of how miraculous it is to be able to create anything at all.

Thanks for reading this!

If you read my last essay of 2024 then you already know that this missive was intended to be sent out before the end of last year. Sometimes things are only ready when they're ready.

2024 was one of my most productive years but I also feel that the intense run of posts and weekly videos that made up the first part of it burned me out and put the dampeners on my ability to create as the year closed out. I have since been able to pull myself slowly out of that state of inertia but I don't want to throw myself back into that state of pre-burnout mania either.

I also think it's fitting that this post was ready at the beginning of a year rather than at the end, with all its commentary about blank pages. I can only take this to mean that the New Year is not a blank page, it is a neatly folded napkin that I am more than welcome to smear with face grease, crumple up and dash onto a dirty plate – or I can use it to make something less precious than what I might have done with the loaded and foreboding blank page.

I think that, in the year to come, Rusty Niall might branch away from some of its old habits and get back to that basic level of things, reminding myself of why I take pleasure in writing in the first place and if ends up in the ecquivalent of a ZX Spectrum text adventure that managed to sell four copies mailed out from a bedsit in Kettering, so be it.

Cheers,

Niall

Don't miss what's next. Subscribe to Rusty Niall:

Add a comment: