What did Transcendence (2014) Get Right About AI and Freedom?

2024-03-29

This essay contains plot spoilers for the 2014 science fiction film, Transcendence, as well as discussion of the final shot of Christopher Nolan's Inception.

I often find myself wondering what sci-fi film could be the next Blade Runner, in the sense that nobody would care much for it at the time of release but decades later it would be reappraised in the light of its poetry and prescience. For a while, I thought that the film that fitted the criteria was Wally Pfister's Transcendence and often thought that I would one day provide the world with a work of criticism that would catalyse this collective shift in perspective.

Well, I decided that this week's essay would be the occasion for that moment, so I watched Transcendence again (this would be my 3rd viewing I think) and … I've started to agree with the critics and audiences of the time.

But I don't think there's much point to revisiting Transcendence ten years later just to add to the kicking it was given on its release. So for the purposes of the rest of this essay, I'll come at it from the perspective of the things I tend to appreciate most in sci-fi cinema – visuals and ideas.

Before that, allow me to bring you up to speed with the plot synopsis. The film tells the story of Will Caster (Johnny Depp), a brilliant computer scientist who is working at the forefront of AI, alongside his wife Evelyn (Rebecca Hall) and their friend Max (Paul Bettany). At the beginning of the film, an anti-AI terrorist group called R.I.F.T (Revolutionary Independence from Technology) attacks his organisation on multiple fronts and Will is shot after giving a talk. While the shooting doesn't kill Will outright, the bullet was contaminated with polonium and Will has a few weeks before he succumbs to radiation poisoning. Despite some initial reservations, Will undergoes a thorough brain scan and the contents and functions of his brain are transcribed digitally. Will dies in his sleep and his digital likeness is activated and, after being set loose on the world wide web, becomes more powerful and intelligent at an exponential rate.

Transcendence's visuals still hold up, as they should. Pfister was the director of cinematography for all of Christopher Nolan's features up to The Dark Knight Rises, winning an Oscar for his work on Inception. With his previous films he was just as accomplished at shooting intimate moments of great importance (think the final shot of Inception) or massive trucks flipping over in the streets of Gotham City for The Dark Knight. And while he is not the director of photography for Transcendence (that duty fell to Jess Hall), there are plenty of echoes of his earlier work in the film's imagery. The subtle lingering on a little detail in the final shot of the film calls back to the aforementioned shot at the end of the film that bagged him an Oscar.

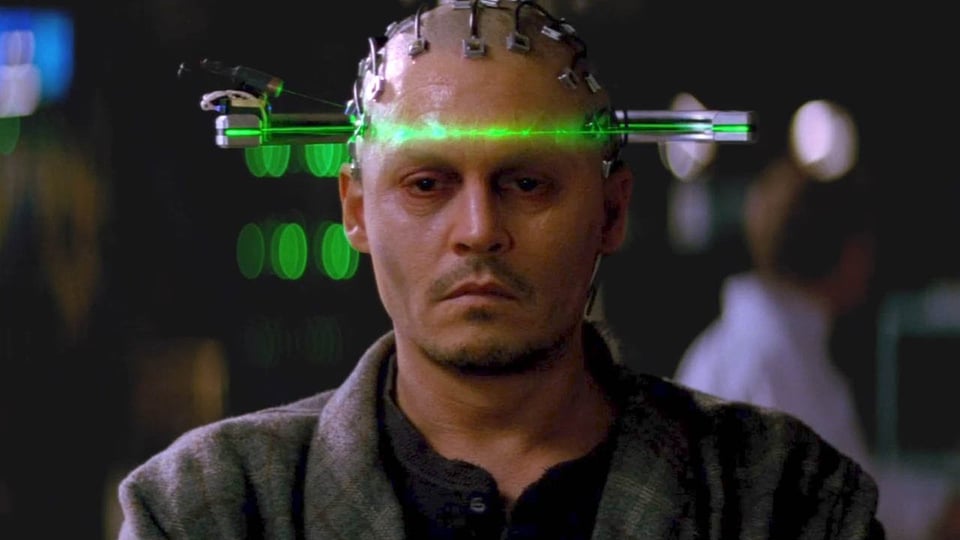

One of the strongest images, one that featured heavily in promotion, was of a shaven headed Will Caster with wires and electrodes plugged into his skull. Being that this is at the point where Will is close to death in the traditional human sense before his subsequent digital resurrection, the wires and circuits represent a kind of cyberpunk riff on the crown of thorns. A later shot of a sunflower being brought to life by Will's sentient nano-particles echoes the Lazarus scene in the greatest New Testament adaptation, E.T. (Oh, I could go into more detail but that really is for another time).

So with the imagery unsurprisingly holding up, we can look at the ideas. One central concept of the film is the idea of what humanity is and whether those same properties can be transferred to or shared with a digital AI. The other central concept of the film is interestingly something that seems to have lost its cultural cache as AI becomes a part of our daily lives, something that William Gibson dismissed as "The Geek Rapture" – the singularity, the moment when artificial intelligence overtakes human intelligence.

Our understanding of AI mirrors our understanding of intelligence – there is nothing singular about intelligence. Intelligence refers to a number of different proficiencies and aptitudes, a spectrum of the multiplicities of our mental lives. AI is already better than us at lots of these things. Only this week there was news about AI successfully detecting the early signs of cancer, albeit in a way that produced enough false positives to need further confirmation from a human doctor.

The more that we incorporate the disparate aptitudes of AI into our lives, the more ridiculous the idea of a unified, conscious digital intelligence seems to be. Perhaps I am wrong here, but as AI has worked its way into the most mundane elements of our culture, it really seems like the idea of the singularity has lost a lot of steam, both in the practical and visionary sense. Similarly, the early plot device where the first moral quandary is whether or not to upload Will Caster's digital doppelganger to the worldwide web. This seems quaint by today's standards, as one can imagine any large project being online from the very beginning, such as the scrapers that were set loose on the internet to scrape all the text and images that they could, mostly without the consent of the creators of those works and texts.

The other question the film asks – what is humanity and can it be reproduced as an AI – is one that we still face today, although Transcendence doesn't do a great job of answering it.

Early on, Max makes a good point that we don't yet understand the human brain so how can we say if an AI is actually conscious? But at another point in the film, as Caster undergoes the brain scans to preserve his mind digitally, Max sounds a note of caution – saying that if they miss a single memory, a single thought, then the digital copy won't be Will.

By this logic, people with brain injuries or diseases that cause memory loss are no longer their true selves either. Not just that, but you could make the same argument for every human being that has ever forgotten something. Ergo, all human beings.

If a film wants an audience to ask serious questions about the value of humanity in relation to the threats of AI, then it has to communicate the value of those human experiences and interactions. Despite Rebecca Hall doing a stellar job as the emotional nexus for all of the events in the film, the rest of the cast are let down by the material they're working with. Either that or some vital context setting scenes hit the cutting room floor.

As the early part of the film portrays Will's decline and the effort to create his digital likeness, I just wanted him to hurry up and die and rise again as Chat GP-Jesus. I just wasn't given enough reasons to care. Similarly, when Max makes the argument later on in the film that Will wasn't the one that wanted to change the world – that was Evelyn – we can't really recall many moments from what we saw of Will's physical life that exemplified this contrast (he mentions in a speech that his wife wants to change the world and he just wants to understand it but this feels like a throwaway line rather than a revelatory moment). It's one of many points where we're just expected to go with the things people say and the decisions they make without seeing the necessary conflicts and revelations that underlie these shifts.

This is perhaps most exemplified with the terrorists and how most of the film's cast seem to jump over to their side with very little shown of how they were persuaded to do so. One moment, Max is abducted by R.I.F.T. before he goes full-on Patty Hearst and joins them. What is the great revelation that causes him to switch allegiance?

Bree, the glowering terrorist lady (Kate Mara) and implied leader of R.I.F.T., regales Max with a tale about how she also worked in AI research. It turns out that she was on a team that uploaded the consciousness of a rhesus monkey to a computer. As a result, the digital rhesus monkey spent all of its time screaming. She then goes on to tell Max about how she and her friends used to talk about his philosophy and his problems with this kind of technology.

That's it. That's the scene that tells the story of how R.I.F.T. decided to commit multiple homicides and why Max decided to join them. The digital monkey wouldn't stop screaming and because she and her mates liked his work. For all that this film makes of human agency, it repeatedly shows the process of changing one's mind as a series of moments where you furrow your brow at new information and then join the other side with no real moment of moral struggle or epiphany.

Joseph Tagger (Morgan Freeman), is Will and Evelyn's friend and mentor who still works in AI. During the attacks at the beginning of the film, Tagger survives a bombing and poisoning attempt, but still witnesses the slaughter of his colleagues. Needless to say, he ends up joining his colleagues murderers (and his own attempted murderers). Why? Because AI-Will gave him the same answer to a question about how he can prove he is conscious as meat-Will's AI creation, PINN (physically independent neural network), gave him ("That's a difficult question, Dr Tagger. Can you prove that you are?") .

This is worth examining for a moment. The Large Language Models of today have been programmed to give an answer to many queries on the subject of their consciousness. However, like all their answers, these will vary in their wording. How was Tagger to know whether PINN's answer was baked in by Will himself, or if AI-Will remembered the answer and thought it was worth repeating? The point I can make here is that there's space for enough doubt before Tagger decides to join the people that murdered his colleagues without a single moment of internal conflict.

It should also be noted that the big, shocking moment of revelation for the threat that AI Will poses to human agency is told through the story of Martin (Clifton Collins Jr), the hired foreman for all of the Caster's construction work. While working alone at night, Martin is set upon by some local ne'er-do-wells. Seriously injured, he is brought into the lab where AI-Will is able to heal and regenerate him while adding some further enhancements. Soon, Mick is back to work, lifting massive mechanical parts that would normally need to be lifted with a digger or crane.

The intended moment of shock comes when Martin is chatting with Evelyn one moment and the next he is talking in Will's voice, saying that they can finally be together. This is the moment where it is revealed that Will can take over control of Martin whenever he wishes (as well as all of the other people he has "enhanced" while curing their physical maladies). But, beyond the shock that registers with Evelyn, (Rebecca Hall once again carrying the film), what has been established about Martin's humanity? All we really see of him is what most rich people see of the proletariat – a useful dogsbody whose occasional vocalisations of doubt and dissent are swiped away by a declaration or demonstration of wealth ("And by the time you and I are done talking, we'll own this diner.")

Again, being that one of the film's central moral dilemmas is about artificial intelligence eclipsing humanity, the film never really explores the inherent value of that humanity, it just takes it as a given.

So, despite me saying I wasn't going to spend time giving the film a thumping, I've done exactly that for the majority of this essay. As I said, the things I find myself most interested in from a sci-fi film are the visuals and the ideas. With that in mind, I really think that there is one idea that this film deals with that very few films, from America at least, want to explore. Whether it intends to or not, Transcendence asks this question:

What if any entity could solve all of the problems facing humanity today: scarcity, the environment, health? All things can be healed. The price of this healing? A little bit of your personal freedom and agency.

I don't know if it was Pfister's intention but R.I.F.T. and their growing coterie of easily-swayed, rational allies are obviously on the extreme end of this scale.

For them, nothing is more valuable than human freedom. The health of the planet, the physical health of their fellow humans and all the other major problems are ultimately expendable if they impinge on freedom. Maybe this is the democratic socialist in me speaking, but that feels a little bit extreme. I have often thought about this dilemma and have wondered what would happen if Transcendence was set in a Scandinavian social democracy, or an East Asian country where the idea of collective endeavour is more important than that of the individual. I can imagine the film being a lot shorter in that context:

"A super-AI is about to heal the environment and cure all illness and all it needs is a donation of our individual liberty? Great! How much freedom would they like?"

I can only guess that Pfister and the makers of Transcendence are convinced that audiences are as easily persuaded as the characters are in siding with the aims and motives of R.I.F.T? But to me, with their viruses and violence and the fact that they knock society back a hundred years or so by wiping out the internet, they seem like more of an American Libertarian version of Islamic State and the tech-free society at the end of the film represents their desired caliphate.

I remember thinking, "Freedom Taliban, haha, what a thought?" after my first couple of viewings. And then came Brexit, Trump and the attempted insurrection of January 6th. If the film is prescient about anything, it isn't through its concerns about the singularity – it's through its prediction of Freedom Fundamentalism.

Perhaps the most impactful example of this came during the pandemic. All the countries that went through lockdown experienced a similar request to the one that AI-Will is making. Citizens gave up elements of their personal freedom for the collective health of their nation, their loved ones and themselves.

While some social democracies such as Sweden didn't impose restrictive lockdowns, they did so through a belief in the cooperative and collective spirit of their citizenry rather than through an appeal to individual liberty. This, however, was not as effective as Norway's strategy, which still imposed restrictions but with the high compliance and confidence of their citizenry. Another way in which these tensions play out is through the ongoing environmental catastrophe, where individual liberty to drive your car is often pitted against the ability of others to breathe clean air as well as the effects of man made carbon on the climate.

Then there is the idea of freedom itself. Many libertarian ideals rest on a strain of philosophical dualism that can be found within the Abrahamic faiths, particularly Christianity, with its conception of free will that goes back to the fall of Eden. While many people believe that they exist as an agent that can cause things to happen, whose decisions remain uncaused – this is not the dominant position held within scientific or philosophical orthodoxies. These tend to extol the position that there is no free will, or compatibilism (none of our choices are exempt from causation but we can still see the person themselves as the primary source of their own actions). I won't go into all of this today, I bring it up to point out that the traditional notion of free will does not seem to be supported by our current understandings of behaviour and brain function.

Human liberty and a respect for individual choice is a fundamental good of any society. It is a necessary scaffolding for democracy and for the justice system. But it is one of many similar fundamental goods that exist alongside it: health, education, protecting the environment, freedom of religious belief and practice, employment rights, justice and the basic needs for food and shelter. We often have to juggle all of these goods and most democratic disagreements are over which combination will best serve society as a whole. When we focus on only one good to the degree of excluding all others, this becomes an act of fundamentalism.

The final shot of the film, where some fizzy activity within a small pool of water in a leaf hints that Will's nanobots are still alive within the Faraday cage he constructed in his garden, (R.I.F.T. were successful in "killing" Will by converting Evelyn to their cause and then sending her back to Will to be uploaded, allowing them to send a virus into Will's network and wiping out his earth-healing nanobots). This implies that the technology is not entirely lost, but that it must wait until a better moment before it can be used, if at all. Perhaps these bots can be tweaked to do their work in a way that doesn't compromise on individual liberty or maybe it's more a case of humanity itself developing a more nuanced understanding of what individual liberty is and what its role within a society should be.

I mentioned how this chimes with the final shot of Inception, the one in which Cobb (Leonardo De Caprio) leaves his totem, a toy whose function is to reveal whether the owner is still dreaming or awake, spinning on a table's surface as he rejoins his family. The camera lingers on the spinning top and cuts to the credits before the audience can see if it falls (awake) or not (dream). As Nolan himself has stated, the point of the shot is that Cobb no longer cares, he has chosen his reality and will stay there.

The final shot of Transcendence engenders a similar ambiguity, though the contrast with Inception is that the choice is still available, though it is a choice that humanity as a whole aren't yet ready to take. Despite the lengths the film goes to to show how human choice and liberty are worth defending to the point of using lethal force, it ends on an interesting notion of how sometimes the choice must be preserved and the decision delayed.

So, if Transcendence isn't (in my approximation) the Blade Runner of the 21st Century, is there another film that is?

Yes.

Blade Runner 2049.

Duh.

Thanks for reading this

Apologies for posting this a few hours later than usual. It's Good Friday, so I'm balancing the nips and tucks for the final draft of this essay. An early draft was sent out in error because a child was asking me if she'd eaten enough of her chips and I hit the wrong button as I was checking my word count. Once again, I do not wish to clutter your inbox on a Good Friday evening and offer my apologies.

I am also posting weekly videos on my YouTube channel where I talk through the ideas explored in these essays, you can find them here:

https://youtube.com/@NiallOSullivan

If you are celebrating Easter this weekend then I sincerely wish you a joyous and reflective holiday.

My weekly essays are given freely, there's no pressure to give back but if you'd like to, any of these would help:

Subscribe – A new subscriber always gives me a warm feeling. There's no better indication that you're creating something valuable than seeing your audience grow.

Spread the word – Much like the above, if you enjoyed this or anything else on Rusty Niall, please consider telling someone else about it.

Upgrade to a paid plan of your choosing – If you feel that my work is worth the price o a monthly cup of coffee and it's within your means, you can click the upgrade button and choose the monthly amount you'd like to pledge. It's completely up to you whether it buys a styrofoam cup of Mellow Birds from a burger van on a trading estate or a vodka martini from a Soho members bar. It's all good, it's all up to you and you are free to adjust or cancel whenever you wish.

Say hello! – Comments are always open, I'd love to hear what you think.

Don't miss what's next. Subscribe to Rusty Niall:

Add a comment: