From Sion Hill to the Green Hill Zone

2025-05-16

About a year ago, I posted an essay that compared the opening level of Super Mario Brothers with traditional Japanese haiku. The gist of it was about how Mr Miyamoto and Nintendo had pared so many elements of the level down to its essence and how everything from the sprites to the music to the calibration of the controls felt perfect. This in turn reminded me of how perfectly distilled the images and phrases of Basho's haiku were.

It’s been a little while since I penned my last clutch of haiku. These days, I can't help but feel an irresistible tendency to churn out long, baroque sentences. But, according to may prose stylists who offer guidance over how to compose a regular newsletter, this is not a good thing. I’ve taken some of this advice to heart and often look for these unwieldy accumulations whenever I apply a fly-by-night edit to each post before I send it out.

I love a good long sentence though. I love how it seems to pick up energy as it goes along, threatening to collapse under the weight of so many parentheses, clauses and sub-clauses. Seeing as my previous post about the brevity and economy of haiku waxed lyrical about Basho's frog, it's only right that I appraise the long sentence from the vantage of that most baroque of baroque poets, John Milton.

OF Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast Brought Death into the World, and all our woe, With loss of Eden, till one greater Man Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat, Sing Heav'nly Muse, that on the secret top Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire That Shepherd, who first taught the chosen Seed, In the Beginning how the Heav'ns and Earth Rose out of Chaos: or if Sion Hill Delight thee more, and Siloa's brook that flow'd Fast by the Oracle of God; I thence Invoke thy aid to my adventrous Song, That with no middle flight intends to soar Above th' Aonian Mount, while it pursues Things unattempted yet in Prose or Rhime.

This famous example of Baroque excess comes from the beginning of Paradise Lost, where the opening sentence of the poem unfurls over sixteen lines of blank verse. The structure of the sentence inverts the orthodoxy of subject-verb-object and instead begins with the object (Of man's first disobedience and the fruit...) and takes a whole five lines to get to the verb (sing) and subject (Heav'nly Muse) at the beginning of the sixth line. It then keeps going for another ten lines, throwing out a barrage of commas, a colon and a semi colon, before finally collapsing into a full stop.

If there was an influence most responsible for this, it was that Late Renaissance masterpiece – made all the more poetic by its bevy of translation errors – the King James Bible. While the King James Bible was an obvious influence on Milton (he was after all a puritan and propagandist for Oliver Cromwell), its long sentences (such as this beastie) also kickstarted a chain of inspiration that ran from William Blake's epics to Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass to Ginsberg's Howl and beyond.

After the legendary reading of Howl at the Six Gallery in 1956, Jack Kerouac spoke about how Ginsberg delivered the poem like a Jewish cantor. Ginsberg himself spoke of how the long lines were written to be delivered in one breath, but at the very breaking point of how far that one breath could go. Whenever I read any of these poems, there's always the sense that the long line builds up energy and tension before it finally collapses.

Away from the musical and energetic purposes of poetry, I often find the long sentence also has a home in philosophical prose. I've recently been reading "You Must Change Your Life" by the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk. While it might seem like the title of a self help book, and there are some self-help elements within it, the book itself is a collection of essays inspired partially by the final line of Rainer Maria Rilke's sonnet, Archaic Torso of Apollo. These essays are much more intense and obstinate for the light perusal of the casual reader and part of this is a product of some very long and drawn out sentences that even my editorial mind thought could be cut down into smaller ones.

But there is a certain flow within philosophical thought that cannot be conveyed by atomised, piecemeal sentences. It is as if the movement between ideas is as important as the content of the ideas themselves and the reader shouldn't be afforded a point of separation where they no longer have to hold on to what came before as they approach a new conclusion.

Ultimately, if you find yourself lost partway through or at the end of a meaty, philosophical sentence – you have no choice but to start again at the beginning rather than at a generously demarcated mid-point. This can also lead the reader to slow down and approach each sentence with more care, allowing themselves to build up their understanding and not read the sentence in the same way they might skim a social media post or self help tome.

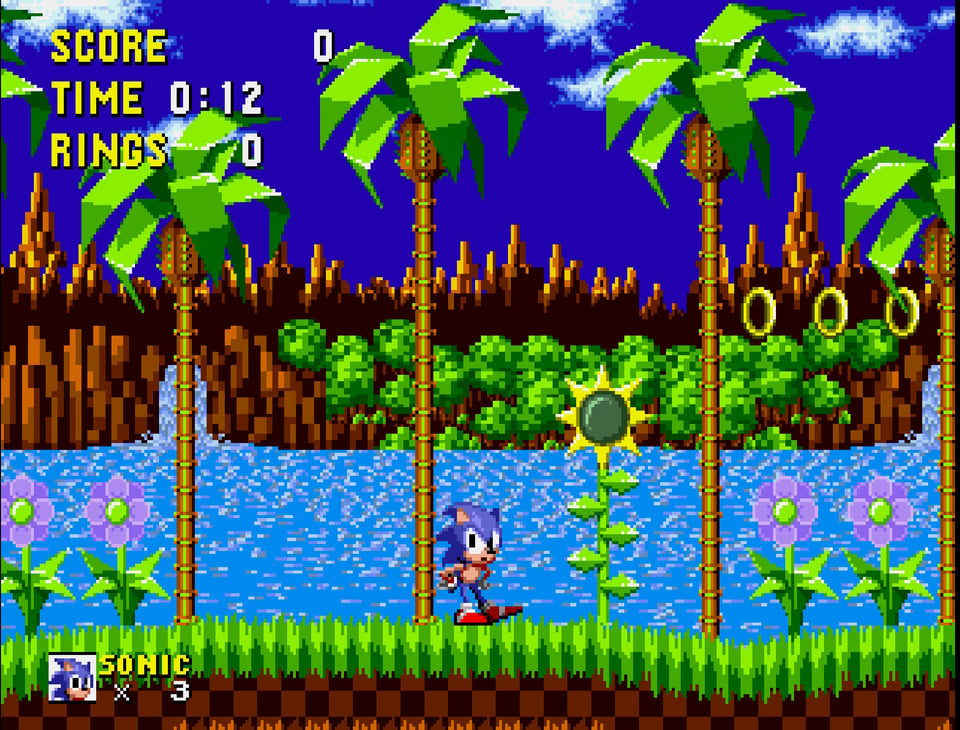

And this leads me to my point about how, if Super Mario Bros level 1:1 features the brevity and economy of a haiku, then Sonic the Hedgehog's Green Hill Zone is the equivalent of the long, discursive, baroque sentence.

The main drive of the levels within Super Mario Bros is forward momentum, signified by a marker shaped like a hybrid of a finish line and a high jump bar at the end of each level. Whenever the screen scrolls a single pixel to the right, there is no way of scrolling it back. There is only one direction of travel and so the choice for the player is between sprinting to the finish line or tentatively timing their jumps about platforms and enemies.

At the time of his launch in the early 90s as the mascot of the Sega Megadrive console, Sonic was marketed as the faster, edgier contemporary of Mario. This was true as far as the sprite itself was concerned. With his sleek, go-faster spikes and his red and white trainers, Sonic leaned headfirst into his running animation before becoming the proverbial "blue blur" – spinning down hills and round loop-the-loops. If the player resisted the urge to send him headlong towards the finish line and put down their controller for a few seconds, Sonic would break the fourth wall, glaring at the player with a quizzical expression as he tapped his toe with impatience. Even today. everything about the character feels like a compulsion to accelerate.

Sonic’s environment, however, is a different story. While it colludes to nudge the player into hitting top speeds in order to blast through tubes and launch skywards to collect some hitherto-unreachable gold rings – the environment is also full of little traps, sadistically placed enemies and spikes that can cause an alarming explosion of one's ring inventory and trigger the death animation if Sonic hits the same hazard on the way back down. Similarly, if the player occasionally doubles back or smashes through secret frail walls, they might find shields, bonus lives or lots more golden rings. Deliberate exploration also allows the player to work out the best route for blasting through the whole level in seconds on a later run.

With the Sega Megadrive’s release getting a head start before the rival Super Nintendo console, Sonic also served as a showcase for what the 16 bit console generation was capable of – not just in the speeds that Sonic could hit (though those aforementioned ring explosions would often cause the frame rate to stutter) but also all the fine graphical detail of the sprites and backgrounds. These are the baroque contradictions of the Green Hill Zone and later levels, how it cultivates a simultaneous urge to blast through to the end while at the same time throwing in a series of hazards to temper that enthusiasm as well as a number of opportunities to slow down and explore.

So yes, if the writer is eager to not frustrate their reader or tax their understanding, they might feel better placed in breaking down their sentences into shorter, digestible morsels. But longer sentences or poetic lines can encourage a reader to read in a different way, to slow their pace or become more explorative in how the navigate a sentence. Rather than build up understanding piece by piece, they can slow down or read the sentence a number of times until they understand it in a more holistic way that percieves how ideas can shade into each other rather than being stacked like so many identical bricks.

More than that, I like how the long sentence challenges the necessities of function and understanding: stacking up colons, semi-colons, dashes, parentheses, clauses and sub-clauses to a point where the whole thing threatens to tip over in a sudden calamity that slows down the reader’s comprehension (in the same way that all those lost golden rings slowed down the frame rate of the Sega Megadrive console) – losing itself as it grinds onwards and becomes more of a thing in itself; an aesthetic monstrosity that, in its audaciousness, opens up new avenues for understanding, communication and (above all) fun.

Or something.

Rusty Niall has settled into a pattern of longer monthly essays (like this one) and shorter, informal weekly posts. If you enjoy them, please consider sharing them with someone you think might like them too. You can also support my work through some of the options listed below. Cheers.

Niall

Don't miss what's next. Subscribe to Rusty Niall:

Add a comment: