Bringing a hacker mentality to problematic art

2024-05-30

Being that this is a hot cracker of an issue, I'd like to start out by stating what I won't be talking about in this essay. I won't be talking about the existence or the need for cancel culture, nor shall I argue or speculate about which artists should or shouldn't be cancelled. This essay already assumes that you like, are inspired by or take solace in art that has been created by people whom you might find to be problematic. The solution I will be suggesting centres around a change of viewpoint – to not look at art from an essentialist point of view but to think like a hacker instead.

With that out of the way, I want to look back at a time when I was spending too much time on twitter during its hyper-moral phase before Elon came along and turned it into 4-chan lite. There was a post gaining traction from a poet who had started reading Wallace Steven's collected works in earnest and had noticed two instances or the poet's casual use of racial epithets (once in the text of a poem and once in a title). They then relayed a version of a (true) story in which Stevens had used a racial epithet in response to seeing a photograph of Gwendolyn Brooks. Many tweets chimed in with the sentiments that they will never read Stevens's poems again and would also keep him out of the classroom. One post responded with something along the lines of "throw him in the bin with Larkin".

I understood the anger and the sentiment. If someone decides that, on discovering something about an artist's work and character, they no longer want to engage with their work, then that is their decision and it should be respected. I have no desire to convince anyone otherwise. While I had glossed over the instances of the epithets when I first read Stevens's Collected works, probably rationalising it in one way or another – the account (from Marianne Moore) about his comments on Gwendolyn Brooks was irrefutable evidence of the man being a scumbag.

While Brooks's work speaks for itself, she was an amazing human being who was involved in some of the most important social movements of the 20th Century. Stevens, on the other hand, was the vice president of an insurance firm who liked to spend his evenings walking about a local lake and had a bit of a drinking problem. This drinking once led him into a fist fight with Ernest Hemingway, who lived in the same part of Florida at the time. The fight ended very quickly with Stevens falling into a puddle and needing medical treatment for his injuries.

Yet, there really isn't another poem by another poet that reads like "The Idea of Order at Key West". For all of Eliot's dalliances with eastern mysticism, none of it got close to Stevens' meditations on being and the nature of mind. I once ended a poem with the lines, "Wallace Stevens was a racist jerk./ I love his poetry. I'm glad he's dead." Part of me is absolutely fine with throwing the man into the bin (or a much deeper puddle), but I still love many of those poems. If a better had person had written something like them, then I would read the better person. But there really aren't many poems that read the same as Stevens's and those that do often come as a result of reading and studying him. I'm not saying that those poems are the best ever written, such sentiments are inherently silly, I'm just saying that there aren't any other poems like them. So, I personally don't want to throw those poems in the bin with Larkin … which leads me to the reasons why I haven't thrown Larkin in the bin either.

Philip Larkin is an even trickier proposition than Stevens, in the sense that most of Stevens's work doesn't imply the problematic aspects of his character. It's a lot easier to conceive of some immaculate muse that has chosen him as an unworthy vessel. But Larkin's work is imbued with a small-c conservatism. Many of his works lament a loss of England and a certain degree of Englishness, albeit one that was more threatened by concrete and car parks than other social factors:

And that will be England gone,

The shadows, the meadows, the lanes,

The guildhalls, the carved choirs.

There'll be books; it will linger on

In galleries; but all that remains

For us will be concrete and tyres.from Going, Going (1947)

However, it was the letters that Larkin wrote that formed the basis of Andrew Motion's 1992 biography Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life, that upgraded the small c of his conservatism to a big one. Racism, misogyny and classism were far more evident in his missives and probably made up a large part of his diaries (which were burned after his death). This also combined with a distrust of the formal and poetic conventions that made up Larkin's style from UK avant-garde poets, who were mortified at the success of more traditional forms within UK poetry while poets in the US didn't intend to mend pentameter that Ezra Pound sought to break (I mention Pound deliberately, being that the avant garde have their own legacy of fascism to contend with).

When I started to teach poetry at degree level, I ventured away from the (at the time) familiar ground of the performance poetry degree to cover a literary poetry class. One of the set texts was Larkin's Aubade, a poem about the how the presence of mortality still hangs over the tedium of bourgeois existence.

I ended up giving the students the full background on how problematic the poet was before I read the poem aloud, so the students weren't perhaps at their most receptive to his work. I remember four young hijabi women sat at the back who certainly weren't charmed by my summary of Larkin's life and convictions.

And yet, after I read the poem, one of them said, "From everything you told us about him, I didn't expect to like it. But I did. I think it's because of how you read it out."

We spoke about the poem further, and we all identified the thing that really worked about the poem was the sense in which it realised that particular dread of non-existence. I just assumed that the poem hit the atheists the hardest rather than people who practiced a religion but one of the young women corrected me, "Everybody has those thoughts."

Looking back, I can relish the irony that I, the right-on poetry teacher, had misidentified the beliefs of four young women because of their religion. Whereas the miserable bigot Larkin had written something that touched on their own private thoughts and fears.

So, other than Larkin and Stevens, I also thought about the times that my wife and I saw plays at the Old Vic as a treat to ourselves and how some of my favourite theatrical memories come from that time. There were two Sam Mendes productions, one of The Cherry Orchard (with Simon Russell Beale, Ethan Hawke and Rebecca Hall) and another of The Tempest.

You might also remember that the director of the Old Vic at the time was Kevin Spacey, who we also watched in Inherit the Wind and Richard III. All of these were amazing experiences, with The Cherry Orchard and Richard III being my personal highlights at the time. Then, several allegations were levelled at Spacey from young men, most of them from the time of his Old Vic directorship.

Spacey's acquittal was enough to launder his reputation in the eyes of some but for others, including me, the sheer number of allegations and the difficulty of meeting the burden of proof with conflicting accounts was enough to keep me from feeling uneasy with my memories of his stage productions. I have been on a few juries myself and there were a few occasions where we felt that the person on trial was guilty of the charge but the evidence presented didn't justify the conviction.

I could go on, all the songs, paintings, novels and movies that I can't enjoy as I once did and sometimes feel bad for enjoying in the first place. But at the same time, I thought of the works that I kept revisiting in my memories and elsewhere and how uncomfortable I felt about revisiting them or continuing to enjoy them.

And then I saw a YouTube video that made an interesting point! Hurray!

This one turned up randomly in my feed, I'm not sure why, but it was from an account called rwxrob and his video was called, "Think Like a Hacker (or die)".

While a lot of the video is more geared towards talking to hackers and programmers, there is a neat summary at the end of the video:

hacking is the skill of finding alternative uses for things and understanding a thing more deeply than even the original white papers

The kind of thinking about problematic art that leads to "binning" every work that an artist has created comes from an essentialist mindset about people and art. The work of art is a distillation of the artist's soul and if their soul is impure then the work of art is impure too.

However, if we think like a hacker, we can look at the work of art from the problematic artist in a different way. In the same way that the science of genetics sees the building blocks of life as something that is essentially code rather than an elan-vital, life essence, we can also see the work of art as code as well. In some ways, the hacker doesn't care about where the code comes from or who wrote it, they think of it in terms of how they can use it.

This is perhaps easiest if you are an artist yourself. We can take apart or reverse engineer a poem or a song or a painting and ask questions about how this works for us. We can interrogate ourselves about the pleasure that we are still able to draw from works of art made by people that are harder to feel the same affection for. I have already pointed out that I carried on reading Stevens because there really was nobody else who wrote like him, but that doesn't mean I can't excise ideas and images from his poems and make them my own.

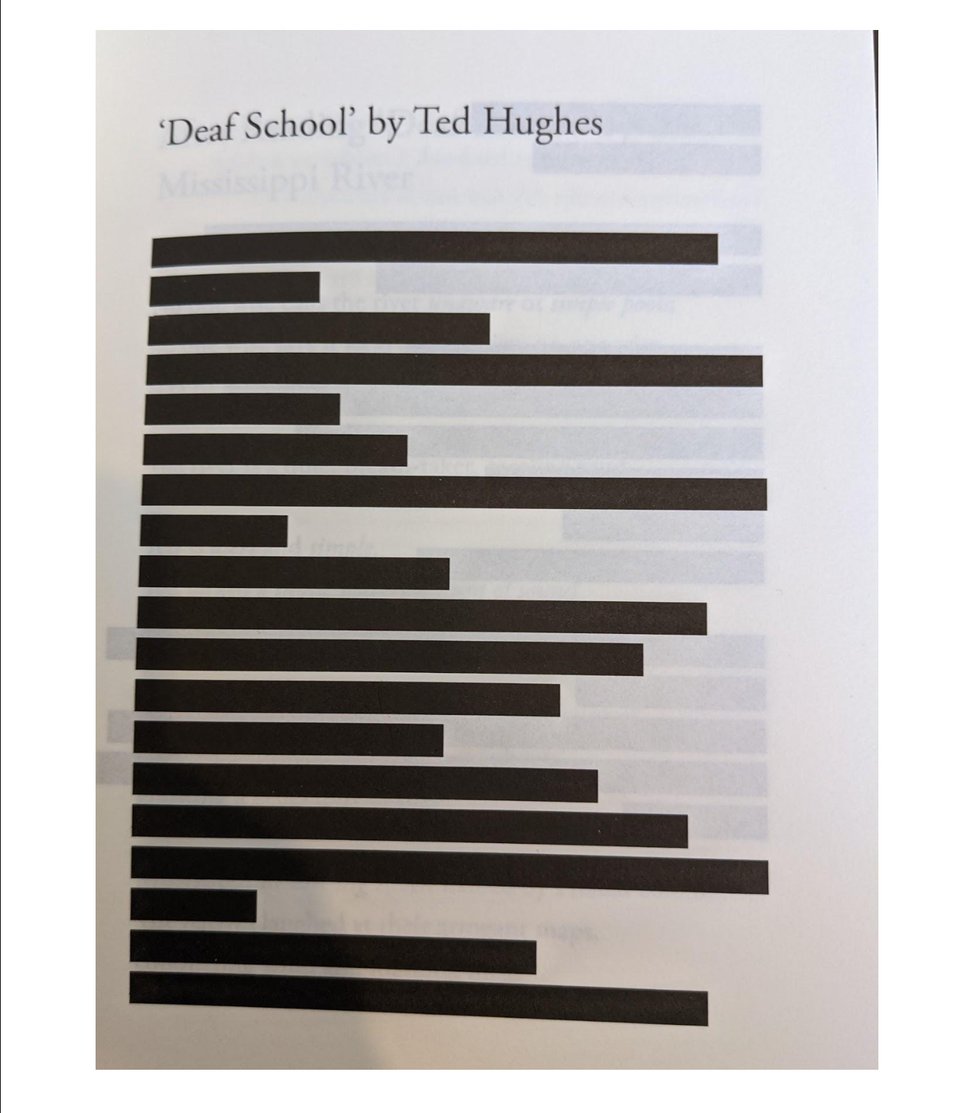

Perhaps one of my favourite example of a kind of hack, one that is almost indiscernible from binning a poet, is Raymond Antrobus's wholesale redaction of The Deaf School by Ted Hughes. In his debut collection, The Perseverance, Antrobus reprints the whole poem but with every line blacked out. In this sense, Antrobus is saying that he has no use for this poem, there isn't a single line that he wants to reuse. However, he does go on to use excerpts from Hughes's poem, albeit in a fashion that maintains his condemnation, with his subsequent poem, "After Reading Ted Hughes's “Deaf School” by the Mississippi River":

No one wise calls the river unaware or simple pools;

no one wise says it lacks a dimension, no one wise

says its body is removed from the vibration of air.The river is a quiet breath-taker, gargling mud.

Ted is alert and simple.

Ted lacked a subtle wavering aura of sound

and responses to Sound.from 'After Reading Ted Hughes's “Deaf School” by the Mississippi River' by Raymond Antrobus

Another thing I like about Antrobus's follow-up poem is how it 'others' Hughes's language through italicising it, in the same way that The Deaf School others deaf schoolchildren in the original.

While I have no truck with plagiarism or the "I was using the poem as a model" justifications for it, I also acknowledge that all art steals from other art in the sense that, when an idea or style is transformed into something else by an artist, it crosses a boundary where permission is no longer required. Hacking a problematic work of art and transforming its favourable elements, or (in Antrobus's case) turning its problematic elements against themselves are ways in which we can use problematic art as a tool to make more art.

But what about people who enjoy art but don't necessarily think of themselves as artists? How can a consumer hack a work of art from a creator they no longer admire, or never did?

One example everybody can identify with is art, usually music, that feels intricately linked to particular memories. An essentialist mentality risks thinking that the memory itself has been corrupted by the work of art that we associate it with. But with a hacker mentality, the song becomes a tool for accessing that memory. In this sense we can play the song to recall the moment, and then make a note of all the other aspects of that memory in the hope of accessing the memory without it. Or we can simply continue to enjoy the song, knowing that our reasons for enjoying it don't stand as some kind of justification of the life or ideas of the singer.

We might also choose not to listen to the song in a fashion that might lead to the artist being remunerated. We could buy second hand physical media or find a copy in the more, erm, nautical areas of the internet.

With my own uncomfortable memories of watching Kevin Spacey's performances, I don't have to necessarily recast him internally (as the makers of All the Money in the World did when they re-shot all of his scenes with Christopher Plummer). I can instead remember the moments that stood out from the prodcution, such as a dialogue between Spacey's Richard and Haydynn Gwynne's Elizabeth.

One thing I remember about the scene was how both the actors found that perfect balance between their own actorly instincts and a faithfulness to the music of Shakespeare's language, especially with regard to how the whole dialogue is written in iambic pentameter, something that was more typical for his monologues. So, in one sense I can remember the performance as a time I witnessed a career highlight for Gwynne, an excellent actor who passed away last year. But I can also bring some of that balance between natural speech patterns and pentameter whenever I read the text of the play itself. The memory becomes a doorway back to Shakespeare rather than an end point.

With regard to Larkin, I keep teaching him, but I teach him as a necessary example of a post-war British poetry that established a mainly white, male academic orthodoxy that continued until the end of the first decade of the twentieth century before the UK establishment was held to accountable for its lack of representation. I teach it as an example of the little England conservatism that we often forget exists beyond the urban and academic settings that many writers currently frequent. I also teach it, alongside Wallace Stevens, as an example of how we can sometimes find common ground with our ideological opposites when we dig deep into our common human experiences and anxieties. And if we don't want to keep returning to Larkin and Stevens as gateways to these ideas, we can reclaim them and take them someplace else. After all, the authors are long dead, and the words they wrote that still manage to penetrate deeper into our psyches are ultimately just strings of code, there for the taking.

Thanks for reading this

If you noticed a bit of a gap between this and the other posts, I apologise. I've been marking end of year assignments and the task just doesn't gel with me being creative and expressive at the same time. This isn't just because of the time it takes, and I'm a very slow marker, but also the way in which marking (and editing other poets) puts me into a mindset that is often counterproductive to me creating my own things. To put it simply, when I spend an extended amount of time adopting a critical mindset, more force is needed to fling open those creative floodgates.

That said, I'm just about at the other side of all of that work so I have a summer to look forward to where (childcare permitting) I can let those floodgates swing open a bit wider than usual. I will probably take a one-week hiatus at the end of August as well, so here's yer heads up for that one.

I'd also like to plug the companion video for this piece as the algorithm's having a bit of a hard time with it. It's probably because I mention the names of a few controversial figures that got picked up by the transcription software and sent it to YouTube purgatory. There's nothing that alarming in the video, I actually thought it was one of the better talks because I didn't have to resort to that many jump cuts this time around.

Thanks for reading this as always. If you would like to support my work you can become a premium subscriber (£5 monthly or £50 annual) you will receive a weekly poem in your inbox on top of the free weekly(ish) essays. Normal service is creaking back into motion, so expect the next poem to arrive tomorrow.

Cheers

Niall

Don't miss what's next. Subscribe to Rusty Niall:

Add a comment: