Blade Runner: Rick Deckard's Ambivalent Humanity

2024-05-13

This essay contains plot spoilers for Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. If you haven’t watched it then you really should.

I had two big insights this week. The first occured when I had to be told it was Star Wars day. In previous years I might have acted with some astonishment on realising I'd forgotten it. But this year, when I was reminded that it was Star Wars day, I simply said, "Oh" and then got on with a day that didn't involve me watching a Star Wars film. I learned, therefore, that I'm not that into Star Wars any more. It was a good forty year run since my family captured the first UK terrestrial screening on our first ever video tape in our first ever video recorder but I think it's over now and that's okay.

The second insight revolved around checking to see if someone has already written an essay on my hot take before I embark on any other form of research. For instance, I might start re-reading Paradise Lost and other critical works that surround it in order to compare Milton's Satan to the character of Roy Batty from Blade Runner.

It was a great take but the problem was that it's already been written by David Desser. While his arguments aren't entirely the same as my own, reading such an article took the wind out of my sails. The point I wanted to make was that, in the same way that Satan is the most heroic character in Paradise Lost (he is the one who faces and often overcomes the most obstacles while also moving the plot forward more than any other character in the epic poem), Roy Batty (Rutger Haur) is the most heroic character in Blade Runner (for almost identical reasons). But one thing I wanted to do in that essay was make more of a comparison between Batty and the seeming human protagonist, Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford). If there is a way to differentiate between Batty and Deckard, it is that Batty just wants to live forever and Deckard just wants to finish his noodles.

Hot from escaping from the off-world colonies to earth, where all replicants (the artificial humans created by the Tyrell Corporation) are banned – Batty (an elite combat model) works his way up to the top of Tyrell Corp’s hierarchy of replicant engineers via a series of interrogations and homicides in the hope of finding a way to circumvent his four-year life span. Deckard, a replicant hunter referred to as a Blade Runner, eventually intercepts Batty at the end of the film. He is clearly mismatched against the replicant and ends up at his mercy, clinging to a high ledge with mangled fingers. However, in the moments before his inevitable shutdown, Batty rescues Deckard and improvises some sublime poetry before maintaining a Rodin pose in the moment on his death.

Deckard’s adventure begins when he is interrupted with a mouth full of noodles and is forced into one more assignment. During the course of the film he will shoot woman in the back as she is running away; be rescued by another replicant (Sean Young as Racheal) who he then rewards with one of the most uncomfortable seductions in celluloid history before he shoots another woman and is spared by Roy Batty.

In my previous Blade Runner takes, I normally fixate on Batty's Nietzschean/Miltonic journey and mildly chastise the casual viewer for being at all interested in Deckard. But it was a return to a text about Milton (in the hope of uncovering some more Batty/Satan parallels) that helped me to reappraise Blade Runner's protagonist.

In “Milton's Satan”, an essay from the Cambridge Companion to Milton, John Carey looks at two different camps of critical response to Paradise Lost, the Satanists and the Anti-Satanists. In the Satanist camp, we have the Romantics (Blake: “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it”) and in the Anti-Satanist camp we have some twentieth century-critics and theologians such as CS Lewis and Stanley Fish.

The Romantics took inspiration from Satan's brave and heroic actions. He is often the one at most risk of danger, not just in his challenging escape from hell and entry to the forbidden realm of Eden, but also in continuing his war against an omniscient and omnipotent God. Whereas the anti-Satanists point out that this bravery is in fact hubris born of vanity. Carey refuses to side with either faction, arguing that it is the most compelling factor of Satan that gives rise to these passionately disparate readings: his ambivalence.

The correct critical reaction to this dispute is not to imagine that it can be settled - that either Satanists or anti-Satanists can be shown to be 'right'. For what would that mean but ignoring what half the critics of the poem have felt about it - ignoring, that is, half the evidence? A more reasonable reaction is to recognize that the poem is insolubly ambivalent, insofar as the reading of Satan's 'character' is concerned, and that this ambivalence is a precondition of the poem's success - a major factor in the attention it has aroused.

John Carey - Milton’s Satan

Interestingly, if we apply this same critical perspective to Roy Batty, he doesn't rise to the same critieria for most of the film. Batty has a singular purpose, to find out how to reverse the controlled obsolescence that has been built into all of the Nexus 6 replicants. The one moment of ambiguity is when, as he approaches the end of his life, his perspective shifts to the point where he accepts his imminent demise and saves the life of his worst enemy – the killer of his loved ones and comrades. We aren't really given many clues as to what is happening within Batty to bring about this change. We can only assume that it is linked to the reason for his programmed four-year expiry date – the development of emotions.

However, when we look for ambivalence among the characters in Blade Runner, I find myself veering back towards Deckard after all, but with a caveat: Deckard is a more interesting and ambiguous character when he's not a replicant.

Just in case you're not up to speed, the "Deckard is a replicant" discourse happened after the release of Blade Runner: The Director's Cut in 1991. This version, which was ultimately tidied up and finessed by Ridley Scott for his Final Cut in 2007, was distinguished from the original by the scrapping of Deckard's noire-ish voiceover and the further scrapping of the ending where Racheal (a replicant with implanted memories who only finds out her own true identity after Deckard tests her) and Deckard drive through some lush countryside after making their escape from Los Angeles. This footage consisted of repurposed B-roll from that famously upbeat movie, The Shining.

However, the change that really struck a cord was the addition of a sequence where Deckard dreams of a unicorn. This recontextualises the final scene where Deckard is leaving his apartment with Racheal and he sees that Gaff (Edward James Olmos), another Blade Runner, has recently visited and left an origami unicorn for him to find. This also implies that Gaff visited the apartment while Racheal, who Deckard has been ordered to “retire”, was sleeping. On finding the unicorn, Deckard remembers Gaff’s parting words following the death of Roy Batty: "It's too bad she won't live, but then again, who does?"

In the version of the film without the dream sequence (which was actually spliced in from footage Scott shot in 1985 for Legend), it is simply one of a number of origami confections that Gaff likes to contaminate crime scenes with. With the dream sequence, it intimates that Gaff knows Deckard's innermost thoughts, ergo, Deckard is a replicant.

As far as the people responsible for the character of Deckard are concerned, there is plenty of ambivalence with regard to his identity. The scriptwriter, Hampton Fancher, was against the idea of Deckard being a replicant. Harrison Ford suspected Deckard was a replicant but preferred to think of him as human and therefore played him as such, while Ridley Scott was explicitly in the replicant camp.

I like the Director's Cut and the Final Cut in the sense that the voiceover and pastoral ending, both of which were inserted at the insistence of the studio, are better off gone. But I also think that inserting the unicorn dream flattens the ambiguity of Deckard and nullifies the moral struggle that he barely rises to for most of the film. For if Deckard works as anything in the film, he works as a human, not a weak replicant with fake memories. Humans tend not to be heroes, we tend to be passengers in the ebb and flow of events rather than instigators and protagonists.

When he's being assigned his mission at the beginning of the film, Deckard tells his superior, Captain Bryant, "I was quick when I came in Bryant, I'm twice as quick now" and makes to leave but is quickly reminded of how little choice he has in the situation. Luck and the empathy from others seem to be the main factors why he isn't dead by the end of the film. It is Racheal's feelings for Deckard that lead her to pick up his gun and kill Leon (a construction model) in the moments before his head is crushed. It is Roy's dawning of empathy that once again snatches Deckard’s life from the jaws of certain death. Of all the characters that we meet in Blade Runner, Deckard is the most resolutely human in a world that most humans appear to have abandoned for the outer colonies. If Blade Runner represents the (still unsurpassed) birth of the cyberpunk aesthetic, then Deckard represents that last gasp of humanity on the planet of its birth.

I have already mentioned the uncomfortable and unnecessary seduction scene, one that could technically be justified in the sense that Deckard doesn't do a single heroic thing during the entire film, so why should his seduction technique be any better? Preceding that, there's a subtler moment where Racheal watches Deckard wash himself at a sink after a busy night where he's hunted down one replicant and narrowly avoided being killed by another.

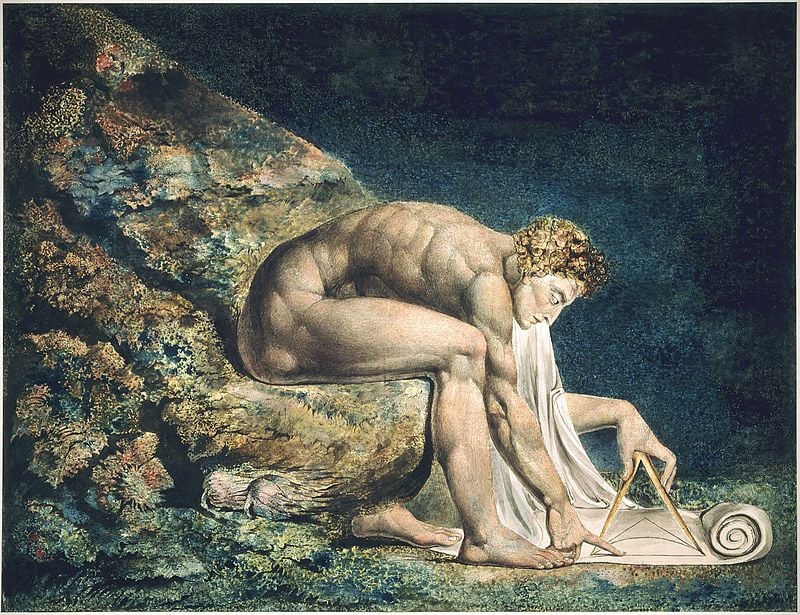

Much like William Blake's famous image of Newton, Deckard is not aware of how physically beautiful he is. The profile composition of the shot is not dissimilar to Blake’s muscular depiction of Newton. But while Blake’s Newton is engrossed in drawing schemas with his draftsman's compass, unaware of his own physical beauty and the beauty of the rock that he's sat on – Deckard is lost in his own exhaustion and pain as he spits bloody water out of his mouth. It is Racheal who can really see him in this moment, not just as an object of attraction but also as a depiction of a species that has mostly vacated the planet that bore it.

In order for Blade Runner to have a clear moral dimension, it is better for Deckard not to be a replicant. If, in some FINAL-Final Cut, the dream sequence was excised again, then there would still be moments that suggest he could be a replicant – the way in which his eyes glow as he's slightly out of focus behind Racheal in the same scene and the collection of photographs in his apartment (replicants in Blade Runner like to collect photographs). But unlike the very specific example of the unicorn dream, these suggestions are more subtle and suggestive, making the point that any human-passing person in the film could also be a replicant.

The genre of Cyberpunk works on a tension between an oppressive, technologically advanced world and its inherent social dysfunction. The concept of transhumanism also comes into play. In Blade Runner, humanity is threatened by the perfection of the replicants. In other Cyberpunk dystopias, human augmentation plays out a drama where the cyberpunk environment infects the human body and ultimately extinguishes its humanity – the anime, Cyberpunk: Edgerunners being one of the best examples of this tension.

In Phillip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the novella that Blade Runner was adapted from, a leaflet declares: "Emigrate or Degenerate! The choice is yours!". The environment of earth in Blade Runner's 2019 is no longer able to sustain humanity, both in a physical and psychological sense. At the same time, humanity cannot sustain its form in the outer-world colonies either. Whether it's the effects of gravity on bone density on another planet, or the impact of varying day and year cycles, humanity cannot remain as it is on another world or a dying earth.

I think this is the “Blade Runner hot take” hill that I'm going to retire and grow old on. Yes, Roy Batty is the real star of Blade Runner, but his brilliance serves to emphasise the story's protagonist, Deckard, who remains resolutely human, even if he might just be a replicant.

Thanks for reading this

Well, to those of you that keep score on this, I'm a day late again. I had a busy weekend that involved a lot of travelling and maybe a few sneaky beers in the sunshine. While I had this essay in a close-to-finished state, I decided it needed a few nips and tucks before it was ready for people's inboxes. When you’re an independent maker it can help to put yourself on a schedule, where deadlines replace the boss or head editor breathing down your neck. But at the same time, lone creators aren’t production lines either and if the work needs more time then the deadline can wait.

I would also like to make a bit of a U-turn with regard to one point I made at the beginning of this essay. There are some advantages to not researching whether somebody has already made the same point in a previous essay. You end up with some highlighted passages and a few pages of notes that all seem to have been pored over for naught. But then, after finding out that your hot take isn’t even tepid, you return to the same notes and highlights again and see if they can reveal new connections and ideas. Reading Desser’s take on Paradise Lost and Blade Runner and then reading Carey’s take on the ambivalence of Milton’s Satan created the perfect conditions for a reappraisal of Deckard instead.

Even if we don’t find a different take, we don’t have to approach culture with what Gil Scott Heron called a Columbus mentality. Just because you aren’t the one to plant a flag into the ground for a particular take doesn’t mean you can’t enhance it or simply advocate for it.

If you enjoyed these weekly essays and would like to support me, you can upgrade to a paid subscription. Paid subscribers also get the perk of a bonus post (normally a poem or yarn) every Thursday and full access to all the poems previously posted.

Also, if you find my patter to be less tortured than my prose, you can watch my weekly videos where I talk through the same ideas as the essays.

Cheers,

Niall

Don't miss what's next. Subscribe to Rusty Niall:

Add a comment: