Where’d All the Money Go?

The $80 trillion wealth drain and where money for substantial public programs may be hiding.

Before getting started, for my Tacoma peeps, Hope and I are headed back to the US this week. We’re going to post up at Proof Bar in Tacoma on the 19th from 5:30 to about 7. If you want to stop by and say “hi” come through. Our time in town is brief, but we also want to be able to champagne & campaign with our people.

Speaking of travel, we recently published a travelog from our time in Budapest over on BowlingsAbroad. Give it a read if you’re so inclined.

Onto the main event.

I know I said I was going to leave affordability and oligarchy behind but I need to dip in one more time to talk about the why of our moment. Why do so many working families find themselves struggling to stay afloat? Why can’t people keep up with the cost of essentials?

You can draw a straight line from the consolidation of a bipartisan neoliberal consensus to the wealth concentration and precarity I’ve documented in this newsletter.

Last week reader P.C. sent along a piece that I’ve been thinking about and sharing with people all week. I’m decidedly not a fan of Substack, nor of AI, but it speaks to the quality of this article that I am going to share it despite those reservations.

The author asks a simple question: What is the economic impact of the reordering ushered in by Reagan?

That order notably was accepted on a bipartisan basis: tax cuts for the wealthy and businesses, stagnant wages for working people, and a perpetual hollowing out of the public sector and services.

In order to find an answer they suggested readers throw the topic at their LLM of choice (this is not an endorsement of AI, I swear).

They wrote:

Give this prompt to an AI:

“How much more revenue would’ve been generated if both personal and corporate taxes had remained at their 1970 levels until today? Take the question literally and give the best estimate.”

After getting that answer, copy and paste this prompt into the AI for a second calculation:

“Do the same calculation again, but this time recognize the stimulative effects of higher government spending on infrastructure, research, and programs that shift income distribution to the working and lower class, as seen in the 1940s and 50s. Assume greater union influence.”

Do that on several AIs. I used GPT, Grok, Perplexity, and Gemini. Go ahead. Actually try that.

I tried it.

The answer for the first prompt was $18 trillion dollars($18,000,000,000,000) in lost tax revenue to provide goods and services to working people. For the second prompt, it gave me a range between $23 to 36 trillion (twelve zeroes).

This is an unfathomable amount of money but to help you try to fathom it, total spending on all construction annually in the US is $500 billion. The total annual spending on all food in the US is $2.6 trillion (twelve zeroes). The cost of all healthcare spending in the US annually is about $4.8 trillion dollars (twelve zeroes).

That is a massive wealth transfer and helps explain why working families feel so strained. Now, you may have your doubts about the data from the AI. So let’s look at a study telling a similar but different tale, this time about wages.

A 2020 paper by Carter Price and Kathryn Edward from Rand called Trends in Income From 1975 to 2018 examined if wages for working people had continued to grow at the rate they were prior to 1975, how much wealth would have flowed to working people. I had Price on the podcast in 2023 to discuss the paper.

His answer was staggering: $47 trillion (again, twelve zeroes). In the paper, they laid out the problem as plainly as two economists ever will:

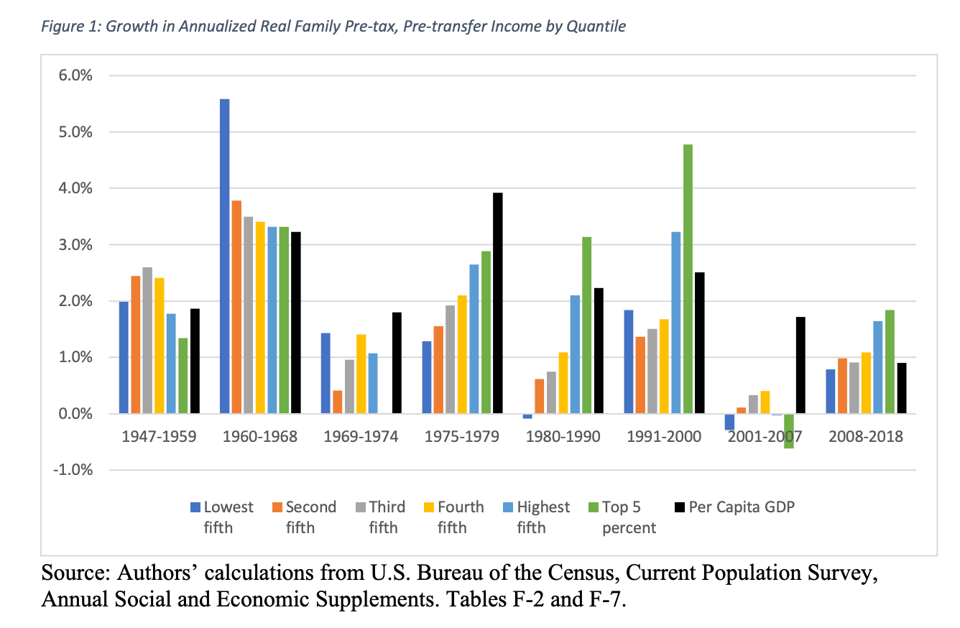

This rise in inequality has been attributed to many different factors including technological advancement, decline in union membership, and globalization. This study does not seek to explain why inequality has increased but, instead, describes how income has changed from 1975 to the present for different demographic groups and individuals across the income distribution. We establish key facts about the evolution of these distributions that can be used to help future studies explore plausible causes and implications of rising inequality. Given that, as shown in Figure 1 (below), the turning point for inequality in income growth in the U.S. was the 1975-1979 business cycle, our discussion will examine the U.S. since 1975.

Forty-seven thousand billion dollars that should have gone to working people in the form of higher wages from 1975-2018 was siphoned off to other places in the economy. Their paper doesn't get into where the money went, but we can do some deduction:

The wage gains never materialized due to slower economic growth post-1975;

Gains instead went to corporations in the form of higher profit margins;

Gains went to CEOs and other executives in the form of higher salaries, bonuses and other compensation;

Gains went to investors in the form of increased share prices and dividends.

Price and Edwards describe it as “a $47 trillion dollar hole in the economy.” And because racism and sexism are both real, the share of lost income for people of color and women tends to be proportionally higher.

So, through tax cuts for the wealthy and stagnated wages for working people, we’re talking about an impact of about $80,000,000,000,000. I feel like I am taking crazy pills even typing that number out.

Sure you can quibble with growth rates, which could tilt the totals downward a tad, and surely there’s some double counting, but this is where the money for the universal programs that similarly wealthy countries are able to provide is hiding.

A Lack of Other Alternatives

In my comparative politics class this week we talked about how the first half of the twentieth century forced Western democracies to confront the appeal of Socialism.

In the early twentieth century, socialist movements were not fringe in the US. Eugene Debs pulled nearly a million votes in the 1912 presidential election, socialists won municipal races across the country, and they helped build a labor movement that genuinely scared the political establishment.

Something similar was happening across Western Europe. Socialism was gaining real traction among workers who were fed up with industrial exploitation and political systems that served only the owning class. Social Democracy emerged in Europe as a deliberate response to this pressure. It was designed to preserve capitalism while absorbing enough of the socialist program to defuse revolution. Universal pensions, public housing, and national health systems: these were not gifts from enlightened elites. They were concessions made to keep Marxism from becoming the dominant political force in the West.

The New Deal served a similar purpose. Roosevelt did not become a reformer out of benevolence. He shifted because socialist parties and candidates were gaining traction and the political class recognized, in plain terms, that they needed to give people something real or risk watching the entire system flip.

I think we are approaching a similar potential point of breakage. People are exhausted with economic precarity and increasingly distrustful of institutions. But unlike the 1930s or the post-war period, there is no broadly accepted left alternative waiting in the wings. Marxist Socialism no longer carries the legitimacy it once had.

That is the part that unsettles me.

Since around 2010, I have believed that if a true rupture came to the US, the people who would seize power would be fascists along with their paramilitary supporters.

People are justifiably exhausted by neoliberalism. And “neoliberalism light,” what Democrats have offered is a losing electoral strategy. The American left has to present a different model. You do not need to abolish markets or private property to get what Danes and Finns get from their governments. You just need a political movement and message that communicates a humane welfare state is wholly compatible with democracy.