How to leave the house

Gimme $2 so I can buy a donut.

This week’s question comes to us from Natallia Shauchenka:

The internet and the world feels huge and hyper-connected, but hella lonely. How do you actually meet people, find cool stuff and turn strangers into friends?

Get a dog.

Look, I know not everyone can get a dog, and we’re gonna get into other suggestions that are also pretty good in just a second ( and… christ, we’re gonna have to get into the whole “loneliness epidemic” aren’t we? Fiiine.) but first of all we’re gonna talk about dogs because it’s weird not to talk about dogs when we’re talking about loneliness. This is why we have dogs, and they’re very good at their jobs.

Erika and I got a dog when we moved in together. I’ve written Rupert’s origin story already, so I won’t rehash it here, other than the parts that have to do with today’s topic. One of the reasons we wanted to get a dog was because we live half a block from a dog park which we could see from our front window, and well… there were people out there, and they had dogs, and both parties looked like they were having a good time. So we got a dog, we got a leash, we got some shit bags, and we all went to the dog park together.

Your first foray into a new environment, be it a dogpark, a public meeting, a cook-out, or a sex party (ask your parents), is always about learning the rules, seeing how the community works, and doing more listening than talking. You need to find out how this shit works. So we slowly walked up to a cluster of folks who were doing dog things. Eventually, one of them asked us our dog’s name. We told him. Then he told us his dog’s name. This was Rule One of the dog park. No human names were asked for or offered. But everyone now knew our dog’s name. Someone said it was a good name. One of us thanked them. We moved a few steps closer to the rest of the pack.

Then came Rule Two: “Can your dog have a treat?” Yes, Rupert can have treats. And thus we learned that you have to ask before you give someone’s dog a treat. From subsequent visits we also learned that the answer is assumed to be true in perpetuity, and Rupert got treats from everyone from that day forward. Unless he was having “tummy trouble” (a scientific term) and then it was on us to let everyone know as soon as possible, and before treats were offered.

Eventually, we learned the names of some of our neighbors at the dog park. We also learned that everyone mostly keeps to a schedule as to when they’ll be at the dogpark. And as we’ve gotten to know each other we come out, we chat, we gossip about who’s not there, we discuss local and national politics, we exchange movie, book, and TV show recommendations, we check in on folks who aren’t there and make sure they’re ok, and we have the occasional park drama that happens when humans get together. In fifteen years of being part of the dogpark we’ve mourned more than a few dogs, welcomed replacement dogs, and also lost a few people as well. And I suppose those get replaced as well, if in a slightly different way. Either way, the losses were always felt. These were our dogs, and these were our people, and when either left us the community felt their loss.

During the pandemic, the dog park was one of the few places where we could get together with other people, if standing further apart and talking a little bit louder. It’s also when we ended up learning a lot of human names that we hadn’t learned yet. Knowing that the dogpark was there, and that there would be humans in it (as well as good dogs) was kind of a life saver.

The story about the dog park is a story about two types of pack animals.

People need to be around people.

Even people who claim not to like other people need to be around other people. (Record stores are proof of this.)

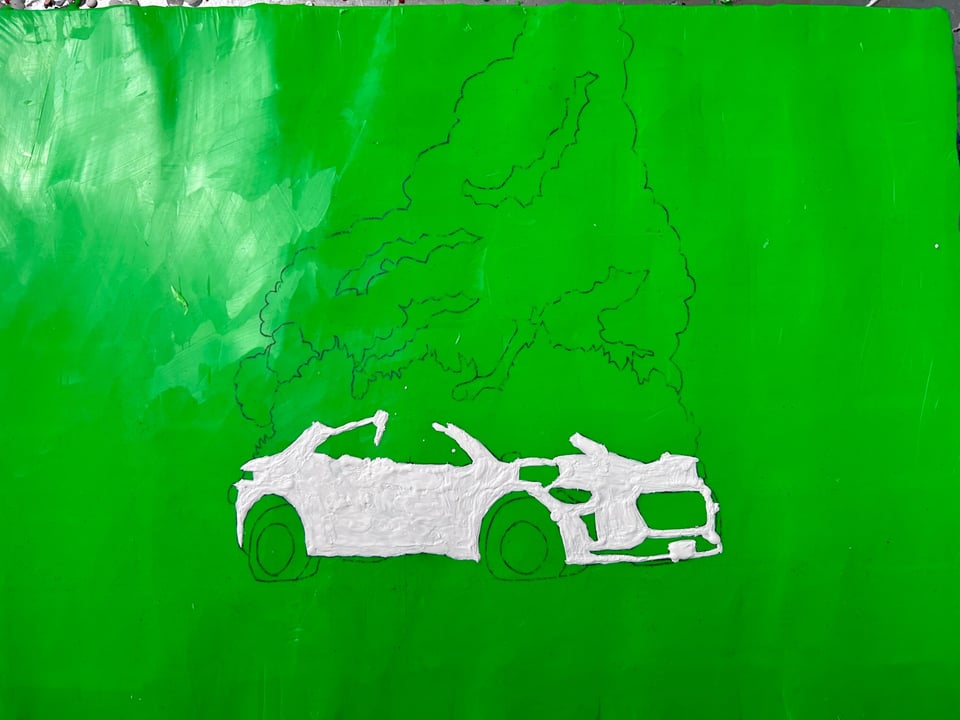

A few years ago I was reading a story about FOX News (know your enemy) and the author (who’s name I apologize for not remembering) mentioned that FOX News’ main goal was to make people afraid to leave their house, to paint such a terrible picture of what was happening outside your front door that you were terrified to ever go beyond it. From personal experience this rings true. Personal experience being phone calls with my mother who is always going on about riots, gangs setting buses on fire, and feral children riding armored pit bulls into combat against “police officers.” All of which she’s seen being reported on TV.

My mother, who immigrated to Philadelphia in 1970s and was always surrounded my an immigrant community that was always within walking distance and included cafés, grocery stores, social clubs and other places where she could talk, gossip, and congregate with other Portuguese immigrants, followed my brothers out to the suburbs.

I grew up in a city. And while I no longer live in the city where I grew up, I still live in a city. I cannot imagine living somewhere that’s not a city. I cannot imagine living somewhere that doesn’t have sidewalks connecting me to places that I can walk to. Sidewalks are a promise. A promise of connection. If there’s a sidewalk, there’s gonna be things that sidewalk connects to, be it a dog park, or a café, or a record store, or a barbershop. A sidewalk implies that we, the city, welcome you to walk through our city, and go to the places connected by that sidewalk, and that in those places you will meet other people, and even if all those other people are strangers, and you don’t say a word to those other people, you will—if for a brief moment—experience the connection of people in the same space at the same time sharing a type of connection. And as slight as that connection may be, it is important.

The lack of a sidewalk is a threat.

The lack of a sidewalk implies that no one in the neighborhood needs the sidewalk to get between things. Therefore anyone walking through the neighborhood doesn’t belong. You are doing it wrong. You are not following the rules. You are not one of us. You don’t below here. In places without sidewalks, people get in their car, drive out to another place, do their business, and retreat back into their home. And while I’m sure they make some form of human connection where they might drive to, there’s a loss in being hermitically sealed in your vehicle during the trip. When I use the sidewalk to go to the record store and come back home carrying a very identifiable yellow Amoeba bag, I can count on at least one person asking me “What’d you get?” during my walk home.

Loneliness is an architectural problem.

We need places where people can come together, and we need those places to be accessible, and free. We need them to belong to no one because they belong to us. Living in a city, I’ve had my share of those places. For a second I was about to say that I’ve been lucky to have those places, except that living in a city isn’t luck. It’s a decision. I decision I want credit for. Then I almost said that having those places was a privilege, except it’s not. Having places where humans can congregate freely isn’t a privilege, it’s a right. And I think to often we call things out as privilege—as if they should be discarded, when the reality is that the real problem is that our rights aren’t evenly dispersed.

Loneliness is a transportation problem.

I ride through the city on my bike. It’s my main method of transportation. When you ride a bike through the city you are part of the city in a way that you’re not when you’re driving through it. There’s no barrier between you and the city. You are touching it and it is touching you. I know the pace of different neighborhoods. I know the smells of different neighborhoods (sometimes this isn’t a positive, but hey…). But riding through the city reminds me that I am part of the city, and that the city is part of me. It’s both humbling and empowering in a magnificent way that reminds me of how community works. As a kid, I remember my father telling us to lock the doors as we were driving though certain neighborhoods, and there are no doors to lock on a bike. Instead, I have to make common cause with the other people in the bike lane, and the people in the crosswalk, and the people opening their driver side door to break my collarbone. We are all navigating the city. We need to listen to what our city has to say. We need to live in it. We need to touch it.

There’s a reason fascists hate cities. Cities force you to deal with your fears. The abstraction of “the other” becomes the reality of neighbors just trying to go about their day, same as you. Good fences don’t make good neighbors, potholes make good neighbors. Everyone coming to a stop when you take a header on your bike makes good neighbors. People sitting with you, until you get over the shock of a bike accident makes good neighbors. A man you’ve never met before, offering to ride alongside you as you bike home (not realizing yet that you have a broken arm) makes good neighbors.

The world of late-stage capitalism is designed to keep us lonely. And while it’s one thing to acknowledge it, it’s another thing altogether to accept it.

The most dangerous thing about riding a bike through the city lately is delivery drivers. The ones on cars will come to sudden stops in the bike lane and then swing their door open without looking. The ones on scooters will weave in and out of the bike lanes. And while, yeah, I wish they were more careful, I also understand that they’re under tremendous pressure to get your order to you under a certain amount of time. The amazing thing about all the delivery drivers is that they’re doing it in neighborhoods that are peppered with all manner of restaurants. And—because I know the makeup of these neighborhoods I bike through—they’re usually delivering food to young people with money (Food delivery ain’t cheap.), who might—and here I’m guessing—be eating their very expensive delivery food in front of their laptop while dealing with after hours work shit. If you are young, abled, living in the city, in possession of a pair of shoes and getting all your meals delivered you might want to rethink the loneliness epidemic thinkpiece you’ve been working on for the last week and just go the fuck outside.

The cure for loneliness might be to leave the house.

Last night, Erika went to a Valkeries game with a friend. I sat at home with the dog watching a documentary about the Poop Cruise. Around 8 o’clock I got hungry, so I rummaged through the kitchen but decided I wasn’t in the mood to cook, so I put on my jacket, got on the sidewalk and took it about three blocks to one of our local falafel places. My intention at the time was to get my falafel and take it home to eat while watching the rest of the poop cruise doc. (I’m not smart.) Instead, I ended up taking a seat and having my dinner there while I watched the folks in the kitchen do their thing, listened in on neighboring conversations, and watched folks walking by on the sidewalk, all going wherever they were going, which was none of my business. Except that at that moment, we were all walking through the same place in time, for the briefest of moments, and none of us were alone.

Much has been said about the loneliness epidemic. And a lot of it is being said by the same people who profit from making us feel alone. They’ve convinced half of us that it’s too scary to leave the house, and they’ve convinced half of us that it’s easier to not leave the house.

We don’t need a Joe Rogan of the left, we need to leave the house.

💰 Enjoying the newsletter? Gimme $2.

🙋 Got a question? Ask it! I might ramble my way to an answer.

🚲 If you are interested in how cities and communities are connected, there are two very smart people you should be paying attention to: Kat Vellos and Alissa Walker.

🍎 Here is a very good article about how Zohran won the NYC Democratic primary.

📣 The next Presenting w/Confidence workshop is scheduled for July 10 & 11. Get a ticket! We have fun.

🐶 Here is a very stupid bandana you can buy for your dog. (Or for yourself!)