How to drink from garden hoses

Today’s question comes to us anonymously:

Can I be happy even if I hate my job?

Absolutely.

Let me tell you about the corner of Duncannon Avenue and Old York Road in Philadelphia. It’s an unassuming corner in the Logan neighborhood, which is just north of North Philly. You have to be from Philly to know that sentence makes sense, but trust me, it does. There’s a County Assistance office on one corner, a library where I spent many afternoons on the other corner, and some homes on the other corners. But what’s important here isn’t what you can see, but what you can’t. Namely, the giant behemoth of a Catholic School and Church that’s a block away on Broad and Duncannon where I spent eight years of my life as a child, forced to wear a suitjacket and tie. And this being the 70s, both items were polyester and the tie was a clip-on.

What was important about the corner of Duncannon Avenue and Old York Road is that once you made a right onto Old York Road, the school crossing guard couldn’t see you anymore. You were free. You pulled off your tie, stuffed it into your back pocket, then took off your suit jacket, and possibly even your dress shirt, and stuffed those into your book bag. (Polyester doesn’t wrinkle.) (Or breath.) And yes, there was an even more complicated ritual that the girls had to go through, but they went their own direction, because 12 year-old boys are objectively terrible while also incredibly uninteresting to anyone except other 12 year-old boys. (And to parish priests, but that’s a story for another time.)

The point is that once we were out of the line-of-sight of the school we were free. We were happy. Sometimes we’d go to the library. Sometimes we’d go to the train tracks so we could make slugs out of pennies. Sometimes we’d just go to each others’ houses and watch cartoons. This being the 70s, no one was expecting us to be home until dinner. We spent our afternoons drinking out of garden hoses and discovering dead bodies in abandoned houses, as the GenX meme goes.

School was part of our lives, a big part to be sure, but it wasn’t our whole life.

Years later I got my first “real” job, by which I mean that it wasn’t a paper route, or mowing lawns, or shoveling snow, or college work study. It was the first job where I typed up a resume, interviewed, was given a schedule, and deductions were taken out of my paycheck. It was at a copy shop, which at the time was a common place to underuse a liberal arts degree. Mostly because you could make free copies for your friends’ bands, and in return they’d put you on the guest list for their shows. (Mind you, their shows were usually $3–5 to get in.)

And look, I’m not going to lie to you, working at a copy shop was stupid fun. We got to play with massive industrial copiers, bindery equipment with very sharp terrifying blades, and talk to the kind of weirdos that come into, and work at, copy shops. We learned how to kill someone’s fax machine thermal roll by taping a sheet of paper together in a loop (after drawing tiny little dicks on it). We had a giant laminator! Best of all, the shop had a bunch of Mac Classics that you could rent by the hour, back when very few of us had computers at home, and if you grabbed a night shift you could use them for free to make zines and band flyers. In hindsight, I kinda loved that job? Which is weird to admit now.

We were also given polo shirts with the company logo to wear during our shifts. They were teal, which is objectively the worst color. And as much as we might’ve (secretly) enjoyed working at the wacky copy shop, that shirt came off the minute your shift ended. You punched your time card, and you tossed your shirt in your cubby, expecting to find it there for your next shift. Unless of course, someone ran your shirt through the large laminator, rolled it up, put it in a tube, and mailed it to another branch. (Yes, that was me, Steve.)

Work was part of our lives, a big part to be sure, but it wasn’t our whole life.

The point I’m trying to make here is that we grew up with a healthy detachment to these places. School and work were a thing we had to do. And I’m not saying there weren’t enjoyable moments, because there were, but when the bell rang, or the shift ended, we were out. We did not love where we worked. We did not rep where we worked. We did not march in the corporate Pride parade. Subsets of us might’ve chosen to hang outside of work, but these weren’t work mandated events. We didn’t stay at work longer than we had to, and we certainly didn’t take calls from our boss on the weekend.

Granted, we didn’t have cellphones or email, so your boss would have to call a phone that was attached to a wall somewhere in your apartment to try to find you, but swear to god, you could always tell by the ring if it was your boss calling. You didn’t pick it up. And come Monday, it was easy enough to tell them you were away all weekend. What am I supposed to do, bring my phone with me? It’s attached to my house, man.

I promise I’m not trying to turn this into a GenX diatribe, but… we were there when it happened. So I’m gonna tell it like I know it. We grew up in an era where people could not find you unless you wanted to be found. We did our job, and some of us were even good at it. We liked being good at it. We took pride in our craft. But when the clock hit a certain number, depending on your shift, you were gone. Off to do your thing.

We were also there when the sales guys at the copy shop got their first cell phones. A gift from corporate, in case people needed to get in touch with them. And I’ll be honest with you, we were even jealous that the sales guys got cell phones because they were new and they were cool. And that jealousy lasted exactly until one of them got a phone call on a Saturday afternoon, during a random hangout in someone’s backyard, when—5 beers and three joints in, ankles deep in a kiddie pool—his phone rang. And we knew one era was ending and another era was beginning.

Fast forward a couple of decades. Work didn’t just become a bigger part of our lives, it started defining who we were. Offices became campuses. Getting lunch, a haircut, working out, game night, dinner, a book club—things you used to do outside of work—became things you could do at work. You were encouraged to do them at work. And, for the most part they were free! What a deal.

You even carry the machine you do your work with you. You carry at least two, if not three, devices on your own body that your manager can use to contact you at any time they choose. And the majority of us feel like we need to reply when summoned. (Especially with all these threats of looming layoffs!)

Work is part of our lives, a big part, and it’s maybe becoming our whole life.

When we think of our community, we’re likely to picture the people at work. Because it’s where we’re spending the majority of our time. This is by design, but it isn’t our design. It’s the company’s design. In that earlier era, when we still drank from garden hoses, losing a job sucked, but it mostly didn’t take your community with it. In this new era, losing a job means getting gutted. Not only do you lose your paycheck, but you lose access to all the people and places where you used to have your non-work-but-actually-at-work fun. And while your old co-workers will promise that you can still hang out outside work (they mean it, by the way), they’ll soon realize that they don’t really do much “outside work.”

The pandemic put a little bit of a dent in this plan, of course, because you were now working from home, but they adjusted quickly to this by keeping you on wall-to-wall Zoom calls for 12 hours a day. Which wasn’t completely sustainable (even though they said it would be) because when your zoom calls are happening on a laptop facing the window, you eventually start peeking out at what’s beyond that window, and you get curious…

Work is part of our lives, a big part to be sure, but what if it wasn’t our whole life?

They want you to return to work, to their simulation of happiness and community, because they’re afraid that if you don’t you might remember that there was a time when you were free. And you were happy. And you drank from garden hoses.

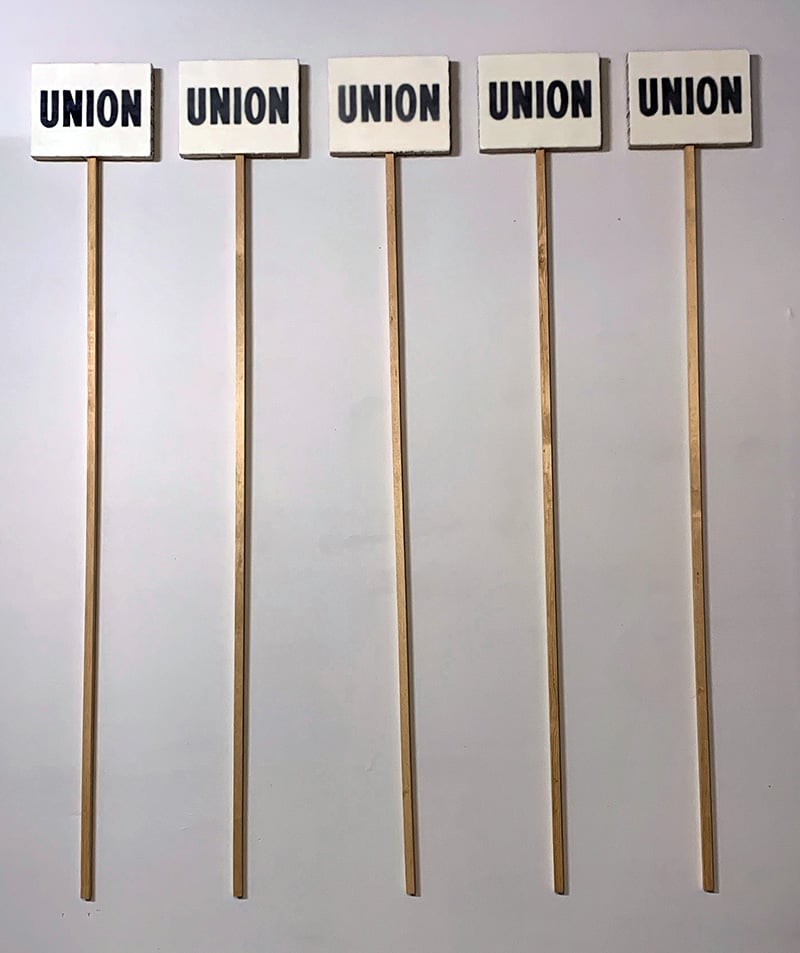

🔗 You will always have more in common with other workers than with your boss. The best time to unionize was twenty years ago. The second-best time to unionize is today. Give the CWA a call and tell them your troubles. It’s like free professional therapy. Unionization is self-care!

🙋 This newsletter works best if I have lots of questions to answer. I know you have one! Ask it. (And yes, you can ask anonymously.)

🖤 RIP Roy Ayers

📚 If the topic if today’s newsletter struck a chord and you haven’t read Ruined by Design yet, give it a shot. (Also available in a Shitty Pulp edition.)

📣 The next Presenting w/Confidence workshop is scheduled for March 20 & 21. If you get nervous talking to people about your work, or doing job interviews, or trying to convince co-workers it’s time to unionize, this is the place to be!