Neo-Victorian Novels: What's Wrong with "Babel"? Plus "Mutual Interest" and "Victorian Pyscho"

A critique of R.F. Kuang's treatment of history in "Babel," plus appreciations of the novels "Mutual Interest" and "Victorian Psycho."

This newsletter is free to the public, and appears infrequently due to my chronic illnesses. If you would like to support me, you can subscribe to my podcast's Patreon here. Although I'm on leave, this still helps. Otherwise, feel free to send me a couple bucks through Ko-fi.

This past week, I finally got around to reading R.F. Kuang’s stupendously popular Babel. This book appealed to me for obvious reasons: it is set in Oxford, and I am an Oxford graduate; it takes place in the early Victorian period, and I completed a master’s in Victorian literature (at Oxford, natch). I had meant to read it when it was first released, but soon got covid, and with long covid the prospect of reading a hardcover book of 542 pages didn’t seem so appealing. (I read in bed, holding books above me, which makes fat hardbacks particularly troublesome.) But after reading an early copy of Kuang’s new novel, Katabasis (out August 26th), I decided to finally get around to reading Babel. I enjoyed Katabasis a lot, though I think it has real flaws, and had felt similarly about Yellowface. Both those books were clever and engaging, but rough around the edges—desperately in need of good editing, which an author who has attained Kuang’s level of commercial success is unlikely to receive. (This is a problem for another day.)

Unfortunately, I soon realized that Babel did not fit into this pattern. It was not a mostly good book with some flaws. Even a book with major flaws can still be interesting, readable, and ultimately enjoyable. Babel is, I suppose, readable enough, thanks to Kuang’s proficient prose, but I did not find it enjoyable or interesting. Instead, I read it with gritted teeth. Babel, despite taking place in the 1830s, is wildly ahistorical in almost every respect: its characters do not behave or speak like characters in early Victorian England and its Oxford bears no resemblance to the Oxford of this period. The novel has other flaws, too: its characters are mostly two-dimensional, its hero an incoherent figure, and characters routinely fail to put two and two together or behave in a rational way. But as a (pseudo) Victorianist, I will focus on Kuang’s approach to history. It is hard to write historical fiction that engages meaningfully with the past and represents the past in an authentic way, but it is not impossible: see the later part of this newsletter for examples. (If you prefer not to read thousands of words on why this book doesn’t work, feel free to scroll down for some briefer critiques and endorsements.) In Babel, alas, Kuang barely makes an attempt to achieve these goals.

Babel is hardly the first work of historical fiction to be written in contemporary vernacular. This can work, if an author approaches the task with self-awareness (and, ideally, humor).1 All too often, however, authors modernize their characters’ speech for no good reason. It’s impossible to fully mimic the cadences of a past time, but the characters in this book speak and think like twenty-first century college students: most egregiously, they critique colonialism and empire using current-day political language, referring to feminism and “brown” people (a term that, if used in the 1830s for some reason, would surely be received as a slur), and so on. Kuang plays fast and loose with the 19th century’s political ideas as well: she repeatedly refers to suffragists, despite the fact that the first public suffrage meeting in England did not take place until 1869. Obviously, there were women and people of color in Britain at this time who were concerned about their rights (and wrote in political journals, or in memoirs and fiction, about the experiences of women and, occasionally, colonial subjects). Black people, in particular, lectured frequently on the cruelties of slavery both in the British Caribbean and in America. But there was no decolonial movement as such, nor a suffrage movement as such, when this book took place.2 It is clear that Kuang’s goal in this novel is to critique the British Empire and, specifically, its relationship to China, but it is impossible to convey the reality of living within that empire as a colonial subject while using contemporary language, precisely because individuals in this period did not have this language at their disposal.

Kuang’s twenty-first century bias extends, perhaps most egregiously, to her depiction of Oxford. Today, Oxford (where Kuang studied for a master’s) is one of the world’s leading research universities, and she characterizes it as such in Babel. Babel, the language institute of the novel, is a pioneering and domineering department, which wards of competition from Cambridge and makes significant leaps forward in the study of translation and specifically language magic. In order to further these goals, Babel recruits undergraduates from the colonies in order to take advantage of their language skills. The book features a diverse group of first-year students: the protagonist Robin (a mixed race Chinese-English man), an Indian man, a Black woman of Haitian descent, and a white Englishwoman. To accommodate their male peers, the female students dress as men. These four students bond as many college freshmen do, studying late into the night, picnicking on the grounds, and going on adventures in London and elsewhere over the course of their studies.

But at this time, Oxford was primarily a training ground for men who would go on to become clergymen. As J. Mordaunt Crook writes, “post-medieval Oxford, prior to 1850, taught little or nothing in the way of law, or medicine, modern languages, or even theology. There was some mathematics, a little physics, a very little chemistry, and of course a touch of divinity. But the bulk of college teaching scarcely spread beyond a conventional range of Greek and Latin texts, plus a smattering of ancient history, logic, and philosophy. The curriculum was extremely limited: students studied Greek and Latin and perhaps some math.”3 Exams were more of an idea than a real practice; students went through a viva voce at the end of their three years but it seems this was basically a formality: “curriculum-based final examinations had yet to emerge.” Crook also notes that no matriculation exam was required to attend the school. (Frankly, lol!)

Around this time, conservative Oxford also got wrapped up in the nation’s roiling religious debates, continuing to insist that its students sign the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England; those who refused were not allowed to graduate, take up a fellowship, or become ordained. Anglicans who objected to one or two of the articles were forced to choose between the Church and their principles, while dissenters and Catholics were not admitted in the first place.4 In other words, in the 1820s and 1830s, Oxford was a deeply conservative and static institution, one that had broken down academically and clung to an increasingly outdated religious code. Reforms would begin in 1850, with the university expanding its curriculum (and beginning to teach women) as the 20th century approached. Writing a novel about the evils of imperialism centered in Oxford in the 1830s doesn’t make a great deal of sense, because it was not the center of… anything in Britain.

Yet Kuang’s vision of Oxford in the 1830s is essentially that of a modern research university transported back in time. Contrary to the historical record, the students take entrance exams and exams during their tenure as students. Robin’s housemates are there to study law, surgery, and classics. (Robin and his cohort are, of course, studying foreign languages.) Never mind that to become a lawyer you became an apprentice, rather than studying at university; never mind that Oxford did not teach surgery (medical school was something of a joke at this point); never mind that everyone studied classics; never mind that other languages (those spoken by living humans) were not studied. Kuang stubbornly recreates the university world that she knows, from big picture ideas to granular details. The scenes of the undergraduates bonding reflect our idea of what college “should” be, rather than any idea of what privileged younger sons destined for the church actually experienced in the early Victorian period. In an annoying author’s note, she defensively explains that she fictionalized certain elements of history, including featuring a modern-style Oxford ball and certain shops around Oxford to which she is attached. But this belies the fact that virtually everything about the book is fictionalized.

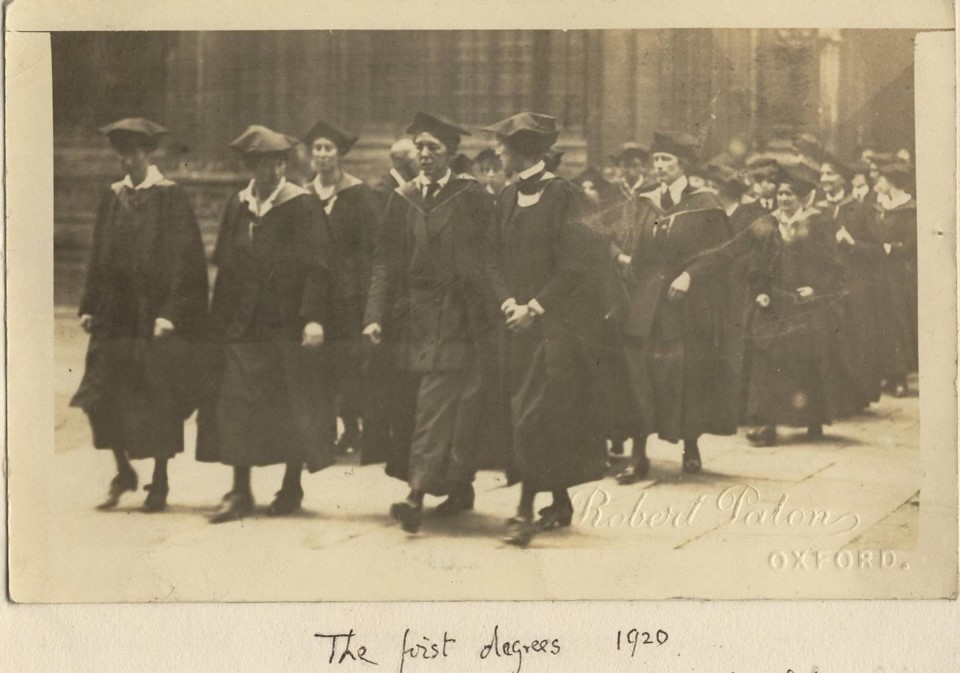

Perhaps most egregious are the inclusion of people of color and women (and a woman of color) in the student body. The first Black woman to earn a degree at Oxford matriculated in 1931, almost a hundred years after this novel takes place. Women were not allowed to take degrees in 1920 (although some had been able to study at the university, not for a degree, earlier). It took Cambridge until 1947 to allow this, despite the fact that their famous women’s colleges had been founded decades earlier. It is simply absurd to think that women would be allowed to study at Oxford in the 1830s, a time when they were barely legally considered people (they could not own independent property if married at this time, could not divorce, and had no independent rights to their children, a situation that could lead to horrifying situations if they quarreled with their husbands). The idea that the problem would somehow be solved by having them masquerade, but only partly, as men, is nonsense: if a women merely walked outside without a hat at this time, it was assumed she was a whore. And people of color would have been rejected even more firmly. Again, this does not mean that women and people of color were not studying or writing publicly. But they were either autodidacts (George Eliot is perhaps the most famous example in England; Frederick Douglass is of course another) or the beneficiaries of forward-thinking (and probably wealthy) parents.

These issues are particularly aggravating to me because I know so much, and care so much, about this historical period, but they should bother every reader, because they prevent Kuang from telling an authentic story. I do not mind a historical fantasy that takes liberties with history: Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell, supposedly a great inspiration for Kuang, does precisely this, but does it within a meticulously researched and recognizable historical framework. The world changes in logical ways based on the existence of magic in that book. By contrast, Kuang wants to make big statements about history and empire in this book, but her grasp of the period is weak, and magic barely changes technological advances, meaning that the social and political condition of Britain (insofar as she describes it) is exactly the same as we know it to be, only with magic. When the students prevent magic from working, enormous buildings and bridges begin to collapse, as though the principles of architecture do not exist.

As limited as Kuang’s conception of these academics is, her understanding of the wider world is even more shallow. When working class Oxford locals show up to support Robin and his revolutionary friends, their leader explains the strategy of barricading the roads around Babel to ward off soldiers. In a footnote, Kuang writes, “If this organizational competence strikes one as surprising, remember that both Babel and the British government made a great mistake in assuming all antisilver century were spontaneous riots carried out by uneducated, discontented lowlifes.” This character’s insight had not struck me as unusual in any way, but Kuang clearly thinks she has to explain to her readers why a member of the working class can have good ideas. She is similarly unimaginative when it comes to China. China has reserves of silver, which is required for her magic system, and they certainly have a wealth of dialects (and surely scholars who speak non-Chinese languages), which is the other required component. Yet Kuang persists in placing China at a disadvantage to Britain. In a novel that wants to critique the British Empire, she cannot imagine a world in which the British Empire is not the dominating force in 19th century history.

As if this post is not already long enough, I want to highlight some recent novels set in the Victorian (or Edwardian) period that, by contrast, handle this historical moment with creativity and insight. The obvious counterargument to Babel is Zadie Smith’s The Fraud, a novel that interrogates Victorian Britain’s relationship to and treatment of race and the Caribbean colonies primarily through the eyes of a middle-class white woman. That character is fascinated by the Black man she encounters, both deeply wanting to help him and unable to help herself from slightly fetishizing him. She is also, despite her very good intentions, unable to understand him. Smith, who does not write in a pastiche style but who has obviously carefully researched this period (and the real life legal case on which she bases her novel), also draws on literary references to deepen her novel’s connection with the literary past.

There are also two 2025 releases that deserve praise and attention. Mutual Interest, by Olivia Wolfgang-Smith, takes place in New York in the early 20th century: a more modern, but still distinctly Victorian, world. Vivian Lesperance, an ambitious and conniving young woman from Utica, makes her way in New York for a while as the partner of a successful female opera singer; after they break up, she sets her sights on Oscar Schmidt, a hapless but professionally successful man (gay, she rapidly intuits) who works in soap manufacturing. Soon enough, the two of them recruit Squire Clancey, a wealthy oddball whose passion for making candles (all of which smell awful) can easily merge with Oscar’s expertise to form a new company. With Squire’s capital, Oscar’s pedigree, and Vivian’s business sense and determination. Soon enough, she is running the business while the two men fall in love.

Wolfgang-Smith’s novel, though it never feels old-fashioned, is in conversation with the Victorian novel in multiple ways. As the 19th century drew to a close, many authors wrote novels about “The New Woman,” i.e., women who (gasp!) worked outside the home (often as typewriter girls or in other semi-professional roles), adopted semi-masculine dress or behavior (riding BICYCLES!), and in general having a life without being married. (There was a surplus of women at this point, leading to “odd women,” as George Gissing explored in his book of that title.) Though these novels occasionally hint at queerness, they obviously cannot go very far in this direction. Wolfgang-Smith, by contrast, can explicitly explore the experience of closeted (and semi-closeted) people in this period, including the lavender marriage at the center of the novel. She also employs an intrusive omniscient narrator, who addresses the reader directly in parentheticals. Though this decision can occasionally feel excessive, for the most part I found it creatively exciting: this narrator reminds us that we are reading a piece of historical fiction, and once again hearkens back to the Victorian novel. Novels of this period often featured omniscient narrators who commented on the behavior of their characters (George Eliot, again, is the most famous example of this, though her tone is more moralizing and less arch).

Meanwhile, while I probably enjoyed Mutual Interest more than Virginia Feito’s Victorian Psycho, I think I admired Feito’s willingness to turn Victorian tropes on their heads in her brutally violent (and often incredibly funny) short novel even more. In this book, a young sociopath named Winifred Notty arrives to serve as a governess at a remote estate in the early fall. As Winifred tells us in the book’s first pages, “in three months everyone in this house will be dead.” In-between her arrival and Christmas, Winifred works on seducing the boorish family patriarch, antagonizing his wife, and then starts murdering people when they get inconvenient. This novel plays with tropes from some of the most famous Victorian novels, most obviously Jane Eyre. In that novel, Jane is virtuous and her romance with Rochester is sincere (despite the latter’s dubious behavior). Here, the relationship between Winifred and her master Mr. Pound is utterly empty and perverse. Winifred also has no maternal feeling whatsoever (as her willingness to kill babies suggests). The novel also evokes Dickens, in particular A Christmas Carol, but whereas Dickens’ orphans are noble orphans and his books full of Christian moral messages, Victorian Psycho has zero interest in morality whatsoever. I am someone who deeply loves the Victorian novel, despite its obvious limitations, but it is nevertheless bracing to watch Feito utterly blow up the form.

I think this is generally easier to do on film, where anachronism can be playfully conveyed through costuming, sets, music choices, etc. But it is not impossible in fiction either. I haven’t read Ferdia Lennon’s book Glorious Exploits, but it’s set in Ancient Greece and written in contemporary Irish vernacular—an intriguing choice that seems wholly defensible to me given how impossible it is to access the language and speech patterns of everyday people at that time. ↩

Ironically, Kuang is dismissive of Britain’s actual antislavery movement, characterizing it as a solely selfish political gambit. While British antislavery was complex, especially in relation to the exploitation of people in (for example) India, there was a genuine and widespread popular movement in opposition to the slave trade and slavery. The issue was debated at length in The Westminster Review, a radical quarterly. Those interested in this subject should check out Bury the Chains, a comprehensive history of the movement by Adam Hochschild, and Black and British by David Olusoga. I also refer readers to Zadie Smith’s The Fraud, discussed below, which considers slavery and race in Britain with considerably more nuance. ↩

From Brasenose: The Biography of an Oxford College. Text here. Thanks good old Victorian Web. ↩

The increased controversy and stress about the XXXIX was a byproduct of the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, and increasing debates over the rights of dissenters, whose civil liberties were also restricted, but not as severely. UCL was originally conceived as a progressive alternative to Oxford and Cambridge as a result of this religious conflict. You can read more about this in Rosemary Ashton’s wonderful book 142 Strand, about John Chapman, the publisher of The Westminster Review, and his associates. Notably, this book focuses on some Oxford graduates who were real scholars, but it is in keeping with my understanding of the university at this time that they left to teach at what was to become UCL. Thomas Carlyle, the leading intellectual of the age, studied at Edinburgh, a significantly more rigorous university. If he were alive today, he would probably have become a professor and stayed within the university system for the rest of his life, but that is not how the world worked then. He was an independent thinker and writer. (Of course, you could actually make a living as a writer at the time.) ↩