"Monet: The Restless Vision," "Paris in Ruins," and the Art of Biography

A joint review of Jackie Wullschlänger's "Monet: The Restless Vision" and Sebastian Smee's "Paris in Ruins: Love, War, and the Birth of Impressionism," along with other fall nonfiction recommendations.

This newsletter is free to the public, and appears infrequently due to my chronic illnesses. If you would like to support me, you can subscribe to my podcast's Patreon here. Although I'm on leave, this still helps. Otherwise, feel free to send me a couple bucks through Ko-fi.

Before I begin, I’d like to share two recent interviews I conducted: with Ana Elena Correa, about her book What Happened to Belén? and the abortion rights movement in Argentina, for Jezebel; and with Cebo Campbell, about his debut novel Sky Full of Elephants, for Electric Lit.

I’d originally intended to write and send this essay and additional recommendations some time ago; instead, maybe some of these titles will serve as Christmas gifts (or gifts for yourself). I aim to send out a Best of 2024 list by the end of next week, also for Christmas purposes; this time I hope I’m on time.

What makes a good biography? This is a question I’ve pondered a great deal over the last couple years: since getting covid in 2022, which led to long covid, I’ve read many biographies, mainly but not exclusively of writers and artists. Though I’ve always been interested in the personal lives of writers, in particular, I found myself relying on these books in the early months of my illness, when I couldn’t read physical books and hadn’t yet gotten used to listening to novels on audiobook. Listening to nonfiction was easier, and books about individuals, full of interpersonal drama, were easiest for me to understand.

Lately, group biographies and histories focused on a slender moment in time have become increasingly popular, offering a novel spin on the traditional cradle-to-grave format. These modes aren’t exactly new — Alethea Heyer published the wonderful A Sultry Month, which chronicled the doings of the Brownings, the Carlyles, and more in the famously hot London summer of 1846 — in 1965. More recently, Rosemary Ashton took a similar approach with One Hot Summer, tackling another boiling London season, this time in 1858, a year in which Dickens left his wife, the Thames was plagued by “The Great Stink,” and Darwin (in the countryside) was perfecting his ideas about evolution. Ashton’s book is chock-full of newspaper clippings, along with letters and other primary source documents, an attempt to recreate three months in a narrow location as closely as it’s possible to do in a few hundred pages.

There’s an obvious narrative appeal to this approach, which encourages a writer to focus on granular human interactions and other details that would probably be lost in longer biographies. The art critic Sebastian Smee adopts this method in his new book Paris in Ruins: Love, War, and the Birth of Impressionism, an entertaining and readable new chronicle of Paris in 1870-71, a year during which the city was under siege by the Prussian army and then descended into the chaos of the Commune after France surrendered. Though Smee’s account is replete with politicians and artists, his focal characters are Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot, two of the only Impressionists who stayed in Paris during the siege. (As aficionados of this period will know, the two also embarked upon a complex love affair, that may or may not have been consummated: Manet was married, and Morisot went on to marry his brother.)

It’s refreshing to see Morisot, a great painter (and the only woman ensconced in the male Impressionist social scene) but one who is often seen in the context of her relationships with Manet and other male artists, given so much attention here, though Smee’s writing about her romance with Manet can be oddly vague. The book is also replete with surreal wartime tales, including the saga of how Paris got mail out of the city via hot air balloons, that remind readers of how ingenious people can be in extreme situations, and also of how much more complicated life was before the telephone.

I found it hard, though, not to compare Smee’s enjoyable book to Jackie Wullschläger’s more formidable, and more traditional, account of Claude Monet’s life, Monet: The Restless Vision, also out this fall. These books are attempting very different things, and there’s no reason not to read and enjoy both; still, as I slowly made by way through Wullschläger’s monumental tome, I found myself appreciating her mastery of the classical form of biography. Notably, Paris in Ruins does not include footnotes, an unforgivable omission for any serious work of history, even one relying primarily (or exclusively) on already published material; by contrast, Wullschläger’s book is heavily footnoted and makes extensive use of Monet’s letters, as well as those of his associates and of contemporary reactions to his work.

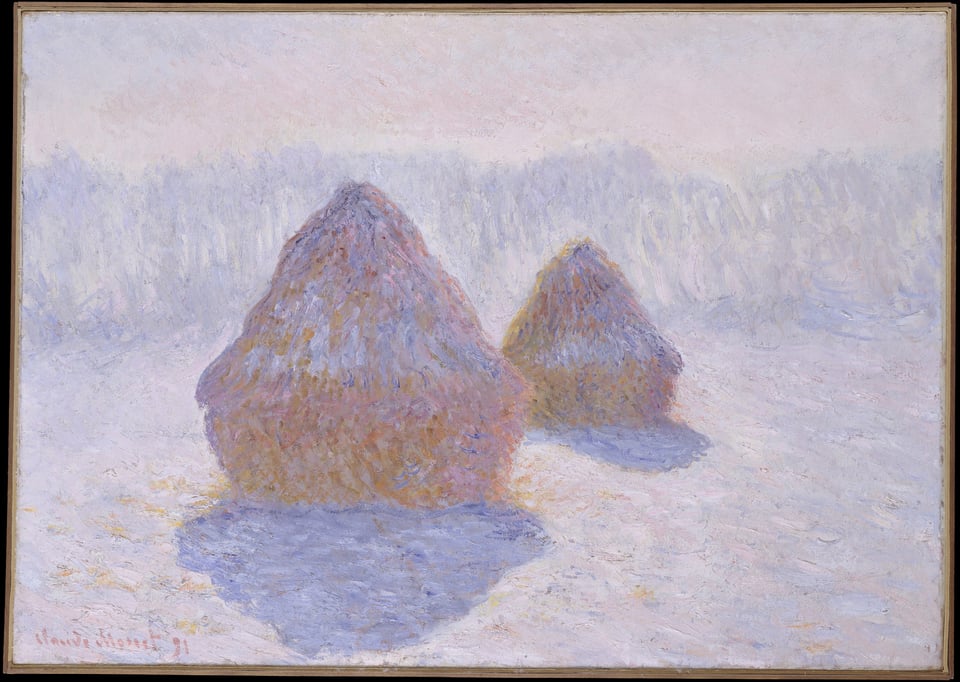

Monet not only paints a fulsome portrait of an ambitious, often histrionic artist — who spent decades failing to manage his money correctly and badgering his friends for loans, or chiding them for failing to provide them — but also of the artistic landscape that Monet disrupted and ultimately conquered. Wullschlänger’s characterization of Monet’s intense commitment to the art of landscape, including his practice of traveling around Europe to find places to paint he hadn’t yet documented — both for his own artistic satisfaction and to make money — and then of his serial paintings (one of which is featured above), is insightful as art criticism and as art history. Monet began his serial paintings once he felt he had no more new vistas to conquer, and they were received as revolutionary and made him even more money because he painted so many images of the same objects. (You have probably seen these paintings in museums, especially if you live in France or the United States, where Monet was popular during his lifetime.) After his long, early period of struggle, Monet succeeded both a consistent artistic innovator and as a man who understood how to market himself and his (prolific) output.

In his review in The New Yorker, art critic Jackson Arn writes that Monet: The Restless Vision “could be called an Impressionist biography of the central Impressionist. Some important events are done in smudged glimpses, but the over-all shape of his eighty-six years is clear. Every few chapters, a sudden nub of detail robs you of your breath.” While I agree with his positive assessment of the book, this characterization struck me as slightly funny. Wullschlänger’s approach is not distinct to Monet but instead a powerful argument for historical biography as a form. It is impossible to truly conjure the life of a person who has died, and inevitably, certain events, relationships, and private beliefs will remain obscured or utterly mysterious to writers attempting to piece together a coherent narrative through the archive. Using primary documents, though, gifted historical biographers can piece together details that give the reader a powerful sense of what their subject thought at a certain time, and how that subject interacted with the people in their life and the world around them.

As he grew older, Monet grew calmer (helped, no doubt, by the fact that he had become spectacularly wealthy), but he was still anxious about his work, growing deeply attached to and never entirely satisfied with the water lily canvases that would eventually be donated to the state and installed at the Orangerie in the Tuileries. I was moved by his compulsive drive to keep working even as he grew very old, but I think I was most struck by Wullschlänger’s description of him as a young person: foolish, dandyish, arrogant, bad with money, and sometimes very rude to his friends. (He was also very handsome.) Most of the images we see of Monet show an old, bearded sage among the water lilies, but a biography — specifically, a biography that takes the trouble to start at birth and follow its subject all the way to the grave — can show us the sides of an icon we don’t already know, or think we know, and so change our relationship to their art.

Other Notable Fall Nonfiction

The Icon and the Idealist: Margaret Sanger, Mary Ware Dennett, and the Rivalry That Brought Birth Control to America, Stephanie Gorton

An insightful dual biography of well-known birth control pioneer Sanger and the much less known Dennett, who also fought for women’s rights and access to birth control but who was considerably less gifted in public relations. This book is, grimly, especially relevant post-election, especially because so much of the book has to do with building activist movements, the qualities that leaders need, and the necessity and danger of compromising core beliefs to make progress.

The Cure for Women: Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi and the Challenge to Victorian Medicine that Changed Women’s Lives Forever, Lydia Reeder (12/3)

This book makes an obvious double-bill with the previous volume, focusing more on medicine itself (and women’s struggle to become medical doctors, and the prevailing sexist ideas that held that educating women would limit their fertility, among others). Putnam Jacobi is a fascinating figure, whom this book argues has a significant legacy that has been underappreciated, but Reeder also expands her focus to other doctors (including male chauvinists) and activists to give a broader picture of this historical moment.

Dangerous Fictions: The Fear of Fantasy and the Invention of Reality, Lyta Gold

Yet another book that feels all too relevant today… in this monograph, Gold uses various recent news stories as well as historical examples to argue against the idea that fictional narratives can be “dangerous” or bad for people (especially children), showing how the right but also the left deploy language that characterizes fiction as the vessel for moral injury or uplift. I didn’t agree with all her arguments, but this book is thought-provoking and, again, vital in the light of the attack on books and free speech we will face in 2025.

Salvage: Readings from the Wreck, Dionne Brand

Another thought-provoking study of literature, this time of classics of the Western canon that Brand criticizes (sometimes eviscerates) for their upholding of the logic of Atlantic slavery; more important, of course, is the continued dominance of these texts in the canon hundreds of years later. The longest section of the book focuses on Robinson Crusoe, a book I have on my shelf but haven’t read; I was startled to learn how deeply embedded that novel is in the slave trade. Brand is an extraordinary critic and her work as a poet also comes through in her sentences here; this made me want to seek out more of her (prodigious) work.