Little Dorrit, or: How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love Dickens

This newsletter is free to the public, and appears infrequently due to my chronic illnesses. If you would like to support me, you can subscribe to my podcast's Patreon here. Although I'm on leave, this still helps. Otherwise, feel free to send me a couple bucks through Ko-fi.

Well, I did say it would be a while before my next newsletter — it has been a particularly unpleasant couple of months for me. I have a few other pieces brewing, but in the meantime I hope this positive tirade on Dickens tempts you read a big fat old book over the coming winter months. I've also put together a Bookshop.org affiliate page, if you wish to purchase any of the books mentioned here, though I myself listened to Little Dorrit via Libby, the most magical app on my phone. I'm feeling especially fierce about libraries at the moment, in the wake of New York's mayor slashing the city's library budget: please, use your library.

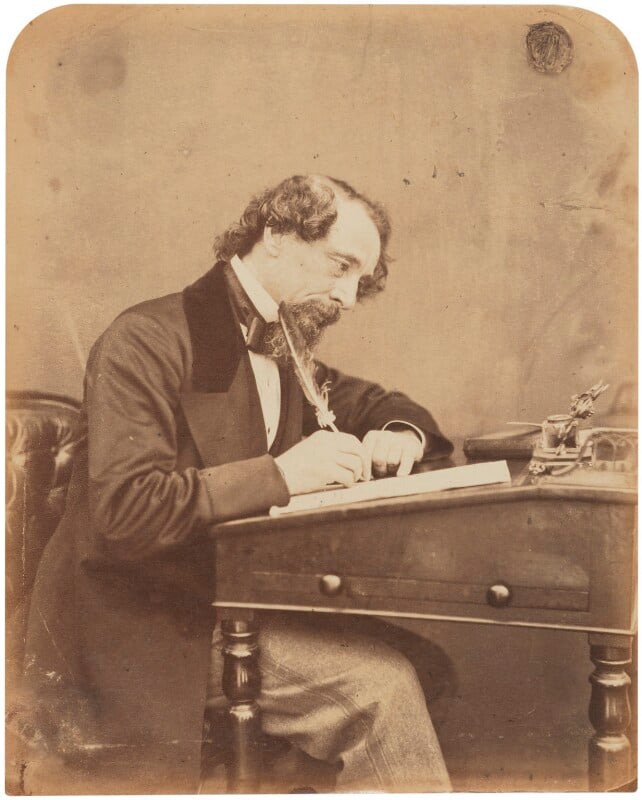

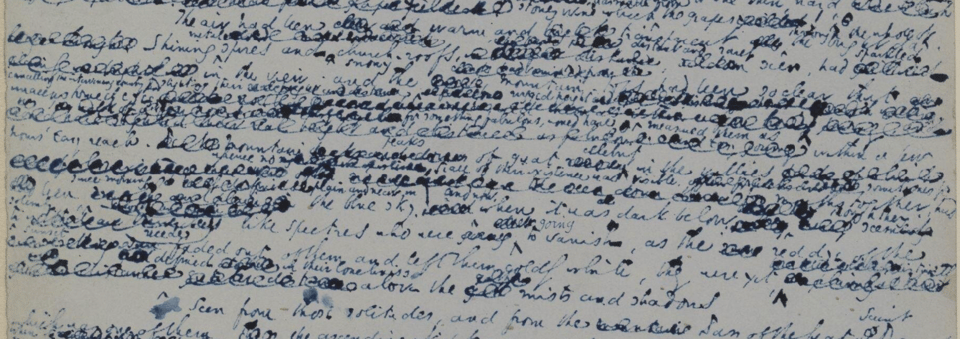

Earlier this year, I decided that it was finally time to familiarize myself with the works of Charles Dickens. Despite literally having graduated from a master’s program in Victorian literature, which I routinely explained to Americans as the period “when people like Charles Dickens wrote,” before this year I had only read two of his novels, A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations, along with his travelogue Pictures from Italy. During my graduate program, Dickens was discussed more often than any other writer, and during that time and in the years since, I’ve become thoroughly familiar with the writer’s personal history (unflattering); his professional enterprises outside of novel-writing, including the publication of the weekly papers Household Words and All the Year Round and his touring performances of his own work (immensely lucrative); and his handwriting (worse than you could possibly imagine). In other words, I could hold a very persuasive dinner-party conversation about Dickens without actually having read him, much.

I deliberately avoided Dickens as a student, partly out of simple contrarianism but mostly because my early experiences with Dickens, particularly with A Tale of Two Cities, prejudiced me against him. The Victorian era, and the long nineteenth century more broadly, was a time of extraordinary literary production by English women writers, including most notably Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, and George Eliot. Many other women were publishing alongside them, especially later in the century — some writing sensationalist or moralizing dreck, but others (like Dickens’ friend Elizabeth Gaskell and the lesser-known but brilliant Jewish writer Amy Levy) producing superb novels that delved into the lived experiences of women. Some male novelists (most notably, to me, George Gissing and the American Henry James) also excelled at depicting the dilemmas and travails of women at this time. And then… there was Dickens.

A Tale of Two Cities, which I read as a young teenager at my mother’s suggestion, features two prominent female characters, the delightfully evil Madame Defarge (who kills people with her knitting needles — at least, as far as I can recall) and the impossibly perfect Lucie Manette, the young blonde love interest. I don’t remember a great deal about this novel, apart from the fact that I was deeply peeved by Lucie and found it, on the whole, overwritten but compelling. As a teenager, I was especially sensitive to and aggravated by this kind of sexist characterization, and my bias stuck with me for many years. I did like Great Expectations, by far the better book, but that, too, is hardly a feminist tract. While the eternal spinster Miss Havisham is memorable and entertaining, she and her adopted daughter Estella are conniving and cold, while the protagonist Pip’s older sister is abusive and cruel. In both books, then, the female characters for the most part fall into two categories: vengeful villain or chaste saint. (Miss Havisham is also chaste, needless to say — but her chastity is unnatural and deforming.)

Years passed, then, without me reading much Dickens, a choice that was no doubt informed by everything I learned and read about Dickens’ own life and treatment of his wife, Catherine. Famously, Dickens abandoned Catherine for the actress Ellen Ternan, who was over twenty years his junior, when he and Catherine were in their mid-forties. By this point, Catherine had borne ten children, nine of whom survived infancy, raising them and keeping the Dickens home with the help of her single sister Georgina. In 1858, however, Dickens wrote to wealthy philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts that he could no longer tolerate living with Catherine, whom he claimed did not love her children: “She has never attached herself to them,” he claimed, “never played with them in their infancy, never attracted their confidence as they have grown older, never presented herself before them in the aspect of a mother. I have seen them fall off from her in a natural — not unnatural — process of estrangement, and at this moment I believe that Mary and Katey [the two oldest daughters]… harden into stone when they go near her.” (Burdett-Coutts was not exactly persuaded by this letter. Later, the Dickens children would feel guilty at the part they played in abandoning their mother.) Although Dickens set up a house for Catherine, after initially claiming she would be allowed to see her children, he quickly banned them from visiting her. Even Georgina chose to live with him. Only the eldest child, Charley, who was old enough to decide where to live himself, remained with his mother. As Phyllis Rose recounts in Parallel Lives, “When their son Walter died suddenly in 1864, Dickens did not even send her a note.” Nor was she invited to her husband’s funeral. (For more detail on the particulars of the separation, I recommend One Hot Summer, by Rosemary Ashton.)

I don’t believe that we should make decisions about which authors to read based on their personal behavior or even, necessarily, beliefs; many if not nearly all writers in Britain’s nineteenth century held views that we would, today, repudiate, and many more behaved poorly toward their wives, friends, or family members. Still, the combination of Dickens’ disinterest in women’s interiority on the page and his cruelty toward his wife in life combined to make me resistant to his work. In the most wonderful type of reading experience, we are subsumed into an artist’s consciousness and world; even if we still find them personally distasteful, we form a strange one-way bond. When we know the author is, in some way, “bad,” this can feel a little like capitulation. And this turned out to be my exact experience when reading — or, more specifically, listening to an audiobook of — one of Dickens’ late novels, Little Dorrit, over the span of a few months this summer and fall.

All of the above is a sensible, contextual preamble for what I really want to say, which is: he got me! After all my years of restraint, and resentment, and stubbornness, listening to Little Dorrit transformed me from a Dickens skeptic to a Dickens fan, an obsessive, a teary-eyed devotee. If I were living in Britain in 1858, the year Dickens began his famous touring performances of his work, I’d be lined up outside a theater waiting to get in and cry some more, like a teenager with Beatlemania in 1963. I capitulated. Earlier in the year, I had listened to an audiobook of Oliver Twist, which I found deeply funny and thrillingly scathing in its criticism of governmental and social institutions that have power over the lives of the young and vulnerable. But it’s also a messy book, obviously written by a writer early in his career, and I didn’t find it a particularly emotional reading experience. Little Dorrit, by contrast, shocked and overwhelmed me with its emotional depth. Though it, too, is often funny and satirical, offering commentary on topics ranging from speculation to government bureaucracy to the perils of wealth, its central characters are vivid and complex in a way that no one is in Oliver Twist. As I listened to the audiobook read by Simon Vance, I was aware of my own pleasure, my own immense emotional investment in the drama’s characters, and also frequently of the strange fact that someone as vain, self-absorbed, and ambitious as Dickens clearly was could write about the travails of other people — particularly, in this novel, other people whose defining characteristics are a lack of vanity, self-absorption, and ambition — with such insight and generosity.

Little Dorrit is set largely in London’s Marshalsea Prison, where Dickens’ wayward father was temporarily imprisoned for unpaid debts during his childhood. In the novel, the patriarch of the prison is William Dorrit, literally known as “the Father of the Marshalsea,” partly due to his decades-long tenure there and partly because his daughter Amy, the “Little Dorrit” of the title, was born in the prison and has lived within its walls her entire life — unlike her more ambitious and worldly sister Fanny, who works as a dancer. Mr. Dorrit, a former gentleman, rules benevolently (and volubly) over his fellow prisoners, or “collegians,” and relies upon cash donations from friends to survive. He cannot, however, bring himself to acknowledge the reality of those donations, or that his daughters work outside the prison to support him and themselves. Though Mr. Dorrit is on some level aware of the various shams and charades he maintains to cling to some kind of respectability, he nevertheless clings to this fantasy, one that demands the obeisance of Little Dorrit and at least the compliance of the much feistier Fanny.

Into this unfortunate situation comes Arthur Clennam, a modest businessman just returned to London from China, where he worked for his own father who has recently died. Clennam, through the convenient coincidences available to Victorian novelists, makes the acquaintance of the Dorrits and becomes unusually interested in their welfare, in particular that of Little Dorrit, who works as a seamstress for his invalid mother. As the novel progresses, Clennam and Little Dorrit form an increasingly strong and unusual bond, despite their different stations in life (Clennam, though hardly wealthy, is hard-working and reliable, and he is almost twenty years older than Little Dorrit). Both these characters are almost implausibly good and virtuous; Little Dorrit, in particular, is something of a living saint, like so many of Dickens’ other female characters. Over course of the novel, she is often put in adverse situations — often as a result of her father — and meekly submits to her circumstances, rather than attempting to stand up for herself.

The relationship between Clennam and Little Dorrit may reflect something of Dickens’ own preoccupations at the time: though Little Dorrit was written before he had met Ellen Ternan and separated from Catherine, it revolves around a romance between a middle-aged man and a much younger woman. (It also features a cruel caricature, in the form of the Clennam’s silly ex-fiancée Flora Finching, of one of Dickens’ ex-flames, Maria Winter, née Beadnell. When he met again in middle age, he found her disappointing and “extremely fat.”) Clearly, Dickens was already feeling restless and unhappy with his personal circumstances at this time, and it is easy to see Arthur Clennam’s accidental romance of Little Dorrit as a fantasy of his own, in which a virtuous middle-aged man is adored by an even more virtuous younger woman. Somehow, though, the romance between Clennam and Little Dorrit mostly escapes potential queasiness, even though Clennam frequently calls Little Dorrit “my child” (a fact that he remembers, uncomfortably, when he finally realizes that their relationship is more than strictly platonic). Although she is young, Little Dorrit is hardened by her family responsibilities, while Clennam’s recent arrival and fresh start in London and his seeming inexperience in romantic matters make him seem younger than his years.

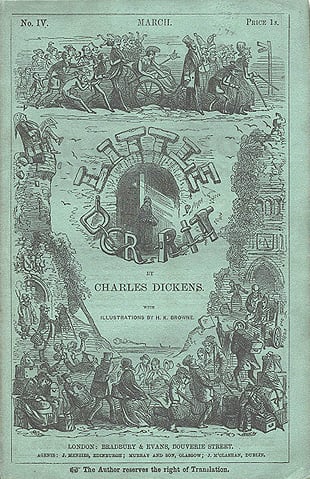

The romantic plot of Little Dorrit is both predictable (they get together in the end) and satisfyingly frustrating (it takes a long time — Amy’s feelings for Clennam are not articulated explicitly until almost halfway through the novel — and for long periods of the book they are separated). Like most great romance novelists, Dickens knew when and how to withhold information and emotional satisfaction from his readers, a skill that was especially useful given that his novels were serialized. (Little Dorrit was originally published in monthly installments, starting in December of 1855 and not concluding until June of 1857.) I derived a great deal of pleasure from taking my time listening to this extremely long novel (the Penguin Classics edition is almost 1,000 pages long), but a few months of reading pales in comparison to the year-and-a-half its original readers had to wait to find out what would happen to Little Dorrit, Clennam, and the novel’s other characters. The ultimate resolution of this romantic plot, though, provides a satisfying and expected conclusion to the book: a happy marriage between the heroine and the hero.

The more emotionally troublesome element of Little Dorrit is Amy’s relationship with her father. Parental relationships cannot, in the structure of a literary narrative, be resolved in the same triumphant manner as romantic relationships; where romances generally end in marriage, parental relationships generally end in death. Little Dorrit enacts both plots. In some ways, the death of Mr. Dorrit is to be expected, and comes as a relief: Amy, who lives for her father, cannot conceive of parting from him under any other circumstances, and when he suggests she marry in the second half of the book, she is alarmed not only because she already loves Clennam but also because marriage would formally sever her from her father, whom she has taken care of since she was a child. Without his death, her character cannot progress forward, even if “forward” only means attaching herself to another man in Clennam. (Interestingly, however, as in Jane Eyre, Little Dorrit places its romantic heroine in a place of power over her male lover when he becomes sick and powerless; both Rochester and Clennam, too, suffer financial/material losses, though Clennam’s are more extreme, appropriately as he begins much lower on the social ladder.)

But before Amy moves on to marry Clennam, she must deal with the death of her father. In the second half of the novel, the Dorrit family’s circumstances are radically transformed by the inheritance of great wealth, which frees them from the Marshalsea Prison and sends them traveling to Europe, where Mr. Dorrit hopes no one will learn of his previous shameful circumstances. He even refuses to discuss his past — and his family’s past — with Little Dorrit, expecting her to rapidly transform herself into a dignified young lady, unmarked by her experiences of poverty. Mrs. General, the woman whom Mr. Dorrit hires to supervise Amy and Fanny’s education and transformation into distinguished young ladies, chastises Little Dorrit for staring too long at vagrants, warning that merely looking at unpleasant things can poison the mind:

it is scarcely delicate to look at vagrants with the attention which I have seen bestowed upon them by a very dear young friend of mine? They should not be looked at. Nothing disagreeable should ever be looked at. Apart from such a habit standing in the way of that graceful equanimity of surface which is so expressive of good breeding, it hardly seems compatible with refinement of mind. A truly refined mind will seem to be ignorant of the existence of anything that is not perfectly proper, placid, and pleasant.

The prescription for Little Dorrit, then, is to forget — to not even be aware of — her own experiences, and the lives of the people she called her friends for the first two decades of her life. This act of psychological severing is not possible, for Little Dorrit or her father.

Mr. Dorrit complains to Amy that “You—ha–habitually hurt me” by “constantly reviv[ing] the topic” of the Marshalsea, “though not in words,” an admission that he himself is often thinking of the Marshalsea, and paranoid that others (including innocent servants) are constantly on the verge of mocking him for his past troubles. Maddeningly, Amy does not ever defend herself or protest against her father’s absurd demands that she obliterate her former life. Instead, she suffers silently. This is, on the one hand, very frustrating to read; I badly wanted her to push back against her father’s emotional cruelty and delusion as I listened to these long, painful chapters. Part of me thought that Dickens had conceived her as too saintly, too feminine, to put up a fight (which her brasher and less morally pure sister Fanny does against Mrs. General’s tyranny, though she too is eager to wash her hands of the Marshalsea). Upon reflection, though, Little Dorrit’s capitulation feels darker to me than mere womanly virtue. There is something masochistic about her willingness to oblige her father, and perverse in her father’s refusal to acknowledge his daughter’s reality. This relationship is not ever satisfactorily reconciled, because Mr. Dorrit is too damaged to truthfully communicate with his daughter before his death.

Here, too, I felt a shadow of Dickens’ future, as though he were writing a version of his own life before he lived it. It’s impossible to know where, exactly, an author gets inspiration, without concrete factual evidence, and surely in crafting Mr. Dorrit Dickens was consciously drawing at least in part on his own troubled father, who as I mentioned above spent time in the Marshalsea when Dickens was young. But Mr. Dorrit also resembles Dickens himself, especially in the wake of the separation that would come in 1858. He was a father who dominated the lives of his children, who demanded that they erase their own histories with their mother to satisfy his own revision of the past. He especially relied upon his two eldest daughters for practical and emotional stability, and was disappointed with his sons, whom he mostly shipped off to the colonies where they died or got into debt (or both).

How much of this dynamic — of Dickens dictating his children’s emotions and behavior — existed before he took them away from their mother? Did some part of him feel a premonitory guilt about his vanity? Or was he merely reenacting his own father’s behavior, recreated here in the form of Mr. Dorrit? There is, of course, no way to know the answers to these questions, and on some level, they are beside the point. Little Dorrit is a marvel, a masterpiece, so wonderful and transporting and funny and tragic that when reading (or listening) to it you don’t think much of Dickens the awful husband and father. Instead you think with awe of Dickens the writer. But the two men were, oddly enough, the same person; somehow, Dickens’ petulant unhappiness, which would lead to unforgivable acts of cruelty, also allowed him to write one of the era’s great novels. Art is funny in this way.