Disability Books #3: Autism Databases and more, plus "Shattered," "Connecting Dots"

This newsletter is free to the public, and appears infrequently due to my chronic illnesses. If you would like to support me, you can subscribe to my podcast's Patreon here. Although I'm on leave, this still helps. Otherwise, feel free to send me a couple bucks through Ko-fi.

Before I get into the body of this post, I want to share two interviews I did that went up in the past couple weeks. The first, with Samina Ali, fits the disability theme. Her memoir, Pieces You’ll Never Get Back, describes her experience of recovering from brain injury during childbirth after suffering from preeclampsia. It’s extraordinary. I spoke to her for Electric Lit, and you can read our conversation here.

I also interviewed the team behind the new film Julie Keeps Quiet, about a young tennis player whose emotionally abusive coach has been fired from her tennis club after a former student has died by suicide. As a tennis fanatic, I was thrilled to see a film that takes the unhealthy dynamics between players and coaches seriously; that said, you needn’t watch tennis to recognize what’s going on in this film. This kind of unhealthy relationship happens in all systems where men have power over younger women.

This interview was for Dirt’s new tennis vertical Strung, and you can read it here. Below, I’m including a couple answers from actress Tessa Van den Broeck that got cut from the final draft:

I’m really interested to hear you say that you were doing some coaching or mentoring of younger players. What was that like?

TVDB: I really enjoyed it. Everything I’ve been through in my tennis career, I can share with them and help them to grow. It’s really interesting to start with the players not knowing anything about tennis, and then two, three years afterwards, you see them playing their first tournaments. It is very mental, and you can get angry on yourself. It’s pretty hard, especially as a kid. So I try to find a way to help them with that, because I know for me, when I was little, that was the hardest part.

The vast majority of coaches of WTA players are men, and both the bad and the good coaches in this film are men. Tessa, can you describe the gender breakdown of the coaches you were working with was, and if that affected you or people you knew?

TVDB: I always had a man as a coach. I never had a woman, because there were almost never women at the clubs—maybe one or two, but they were teaching on a lower level. I want to have a female coach, but there are just no female coaches. I think a man, as a coach, can be harder on you, and maybe a woman can be more like a sister. You can have a better connection and more fun. There were women you can go to, like the people who looked after us at the residence where we stayed. But I think it would be good if there were a little bit more difference. Maybe in a few years.

Now onto business.

Many of you will have seen the news that Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., plans to launch “a new disease registry is being launched to track Americans with autism, which will be integrated into the data.” Though he and the NIH walked back this announcement a couple weeks ago after immediate backlash from patient groups and, uh, every person with basic common sense, he is still talking about the idea. “Every other disease like this has a registry,” he told Fox News on May 5th, raising a number of questions: what registries is he talking about? What “diseases” is he talking about? (Autism is not, incidentally, a “disease”; it is a neurodevelopmental disorder.) He claims this registry would be voluntary and that patient privacy would be respected; color me skeptical.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the Daily Telegraph reports that the UK will require all trans and nonbinary children seeking gender-affirming care will be subjected to evaluations for autism and ADHD. (Charmingly, the Telegraph put “trans” in scare quotes in its headline.) The goal of these assessments is not hard to intuit. As Joan McKibbin writes in LGBTQ Nation, “It’s nearly impossible these days to pay any attention to trans and nonbinary issues without coming across the infantilizing claim — typically purported by TERFs and their sympathizers — that autistic people are being ‘brainwashed’ into believing we’re trans and/or nonbinary, that we are so universally impaired as to be incapable of asserting our own identities or making decisions about who we are for ourselves.”

The combination of these two attacks against autistic people made me hit the ceiling. RFK’s antipathy toward autistic people is well known by this point: though it is only one aspect of his delusional attitude toward medical science (he also does not believe in germ theory), he is particularly obsessed with autism, and of course the vaccines that supposedly cause it. (They do not.) “Autism destroys families,” he has said, calling it “individual tragedy as well.” Autistic people, needless to say, do not see it this way. He has also claimed that “Most cases now are severe. Twenty-five percent of the kids who are diagnosed with autism are nonverbal, non-toilet-trained, and have other stereotypical features.” This is false. According to PBS, “The vast majority of people on the spectrum do not have those severe challenges.” PBS has put together an article fact-checking his ridiculous statements on the condition, which I recommend.

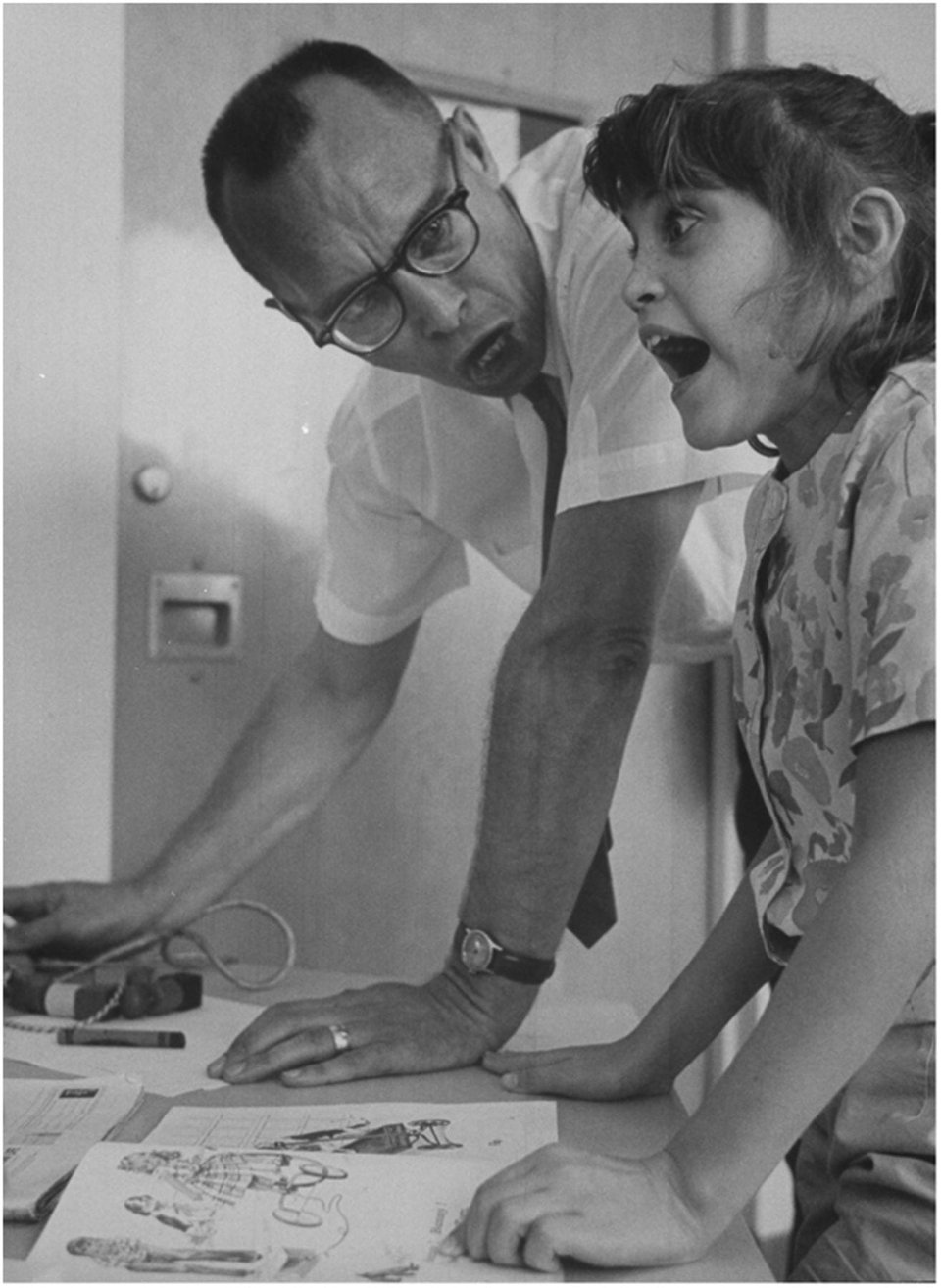

Despite RFK’s singular obsession with autism, anyone who believes that they are safe from his eugenic thinking because they are not autistic should look to the UK, where the government is using harmful stereotypes about autism to persecute another vulnerable population. I found this particularly disturbing because I had just read Steve Silberman’s expansive autism history NeuroTribes, in which he writes about UCLA psychologist Ole Ivar Lovaas’ behavioral experiments on autistic children, which led to the creation of Applied Behavioral Therapy (ABA). Lovaas’ intention was to encourage autistic children to act “normally,” i.e. to suppress behaviors such as stimming or self-injury that would be considered disruptive or disturbing in normal society. This technique has since been adopted widely; many autistic adults have described it as abuse.

It is clear, though, that some current therapists are driven by an genuine urge to help children, even if that urge is misguided; the same cannot be said for Lovaas, who punished his child subjects by spanking them, playing horrifying loud sounds, and subjecting them to electric shock. In his notes, he wrote that “it was definitely painful and frightening.” Disturbingly, his methods were adopted by many parents. Here is another sentence Silberman writes about Lovaas: “He tried to make caddle prods seem less frightening by christening them ‘tingle sticks.'‘“

I describe this grotesque series of “experiments” because they were not limited to autistic children. As Silberman writes, Lovaas “lent his expertise to a series of experiments called the Feminine Boy Project” led by psychologist Richard Green, also based at UCLA. Green experimented on a young boy named Kirk Andrew Murphy, whose parents brought him to Green after seeing Green “interviewed on TV about ‘sissy-boy syndrome’—his term for early-onset gender dysphoria.” This was a form of conversion therapy to which this five-year-old child was subjected. If he played with “masculine” toys, he was rewarded with love and affection, if he played with “feminine” toys he was ignored or “swatted.” The Feminine Boy Project, Silberman writes, “turned into a cash cow for the university, attracting six-figure grants from the NIMH and the Playboy foundation until 1986.” Kirk Murphy died by suicide in 2003.

So the history of suppressing, and indeed torturing, young people who are autistic or queer is inextricably connected. To me this all leads back to the logic of eugenics: the desire to purge society of defectives, “others,” through medical science.

I am not naive enough to think that a book, or books, will somehow cure people of their eugenicist beliefs; still, as I’ve watched these infuriating developments I’ve found myself appreciating the value of books about disability, especially memoirs that allow people to explain their experiences directly to the reader, even more than usual. A book like NeuroTribes is uniquely valuable to anyone interested in the history of autism—or, maybe more accurately, the history of people’s fears about autism—and if you are interested in reading a long history book on the subject, I can’t recommend it more highly. (It’s almost 500 pages but extremely readable.) Most people, though, are probably not going to pick up such a big book. Memoirs can offer insights in more approachable ways.1

Readers interested in learning about autism from the perspective of an adult woman who wasn’t diagnosed as a child (the experience of many autistic women) should check out Marian Schembari’s memoir A Little Less Broken: How an Autism Diagnosis Made Me Whole. For others going through this process themselves, Schembari offers a lot of practical advice and support. More recently, I’ve read two great but very different 2025 memoirs: Shattered, by Hanif Kureishi, and Connecting Dots, by Joshua A. Miele (with Wendell Jamieson).

These books pair together well, despite being so different, because they come at the experience of disability from the opposite ends of life and therefore experience: Hanif Kureishi, an accomplished (and in Britain somewhat legendary) writer and screenwriter, fell in 2022 and became paralyzed, unable to move his arms or legs (he has since regained some, but not much, function in his limbs). At the time, he began posting long threads on Twitter describing his experience, assisted by family members who took dictation. These posts, which have been edited into his book with the assistance of his son Carlo, were candid, funny, and sometimes bawdy (one memorably described a sexcapade in Amsterdam).

Kureishi is not the first older person to suddenly find himself radically physically changed by injury, nor is he the first to write about it.2 But there is something wonderful about a writer of his skill turning his attention and craft to the experience of bodily catastrophe. He carefully describes his emotional and his physical state, sometimes descending into despair in one dispatch, then careening into hilarity in the next. Opening the book to the beginning just now, in which he describes his fall, I immediately saw a stunning piece of writing: “I then experienced what can only be described as a scooped, semi circular object with talons scuttling towards me. Using what was left of my reason, I saw this was one of my hands, an uncanny thing over which I had no agency.” The book is full of gems like this.

Joshua A. Miele is not a writer, and worked with a cowriter, Wendell Jamieson, to write his memoir. (Jamieson had previously profiled him in the New York Times.) Unlike Kureishi, he has been disabled from a very young age: when he was four, a neighbor experiencing psychosis threw acid at his face, leaving him blind and with facial scarring. Thanks to his bohemian upbringing, he was encouraged to remain independent, playing alone outside the family’s Park Slope home. Later, his stepfather, a scientist, encouraged his interest in science and technology. Over the course of his life, Miele has worked to develop accessibility technology for blind people.

Though well-written, a book with a cowriter cannot compete with a book by a bona fide literary star. Yet Miele has a valuable perspective and story to tell. As a child, he desperately wanted to stay away from other blind children, convincing himself that he was special and different—a natural reaction from a child in an era where disabled children typically did not have access to equitable education, yet one that limited his viewpoint and social world. In college at Berkeley, he met other blind and disabled students, discovering the world of activism, and eventually launched onto his life’s crusade of improving accessibility for blind people. He tells many stories criticizing accessibility tools designed by sighted people; for instance, braille on ATM machines, a feature that allows blind people to enter their passcode but not to actually use the machines, which historically relied on a silent screen. In another memorable episode, he made a habit of climbing up street signs to feel the letters, cheerfully explaining to cops and confused pedestrians that he was merely giving himself directions.

Connecting Dots is hardly a perfect book3—Miele’s writing on his wife and kids is pretty bland, as you’d expect from someone who is not out to make a living plumbing the emotional depths—but it is warm, readable, and eye-opening for those of us who have not had to face these kinds of limitations. The more people with disabilities and other marginalized groups are suppressed, the more important these stories will become.

It’s also true that disabled authors are much more likely to write memoirs than any other genre (as Alice Wong and others have written about elsewhere), in large part because our personal stories are seen as more valuable than other forms of creative output we might be interested in. This is a problem—for representation and for the material conditions of writers—but that’s a conversation for another time. For the moment, I think any visibility is a positive. ↩

In fact, his friend Salman Rushdie’s recent memoir Knife, which described the aftermath of the knife attack that almost killed him, follows a similar pattern, though Rushdie was able to recover vastly more physical function than Kureishi. ↩

If you are going to read one book about blindness in current-day America, make it The Country of the Blind by Andrew Leland. ↩