Andy Murray, Emma Raducanu, and the Body's Demands

This newsletter is free to the public, and appears infrequently due to my chronic illnesses. If you would like to support me, you can subscribe to my podcast's Patreon here. Although I'm on leave, this still helps. Otherwise, feel free to send me a couple bucks through Ko-fi.

Today, we take a digression into the world of sports.

July is Disability Pride Month. Perhaps, if I’d been on top of the calendar, I would have pitched an article or two with this in mind; instead, I’ve spent the last few days thinking about some of the most public examples of physical fallibility and chronic health struggles we have: professional athletes.

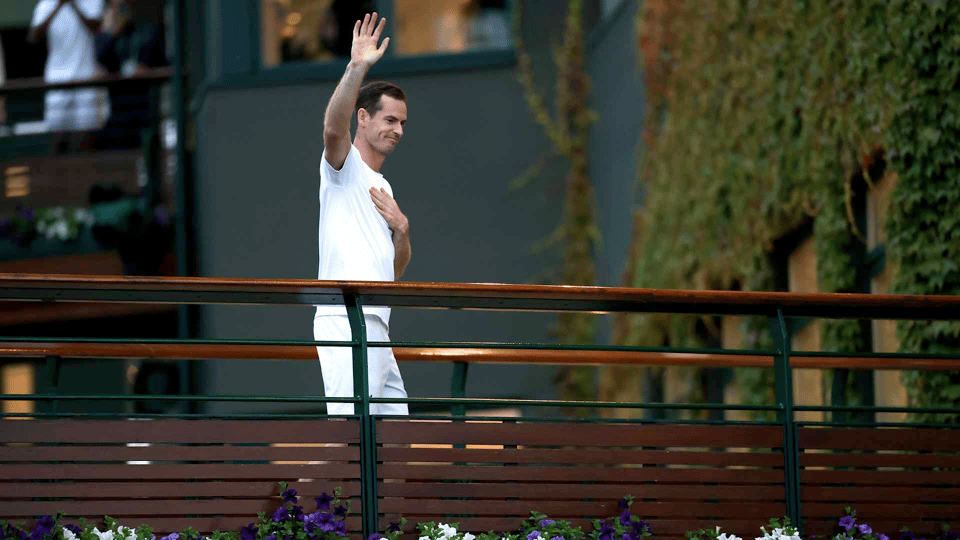

Last week, Andy Murray played his final match at Wimbledon, partnering with his brother Jamie as a doubles team. For the first set, they were surprisingly competitive, thanks largely to Jamie’s heroics; eventually, however, the skill (and comparative health) of their opponents, Rinki Hijikata and John Peers of Australia, overwhelmed them. Andy Murray’s appearance on the court was, itself, something of a miracle: on June 24, he had surgery to remove a spinal cyst. Though he insisted that he wasn’t worried about further injuring his back by playing the tournament, it was possible that the “wound” would cause problems if his stitches were pulled out while he played. The recency of his surgery, which was precipitated by an injury at the Queen’s Club tennis tournament leading up to Wimbledon, prevented him from playing a final singles match at the Championships. Even playing the doubles, I would argue, was an act of minor madness, characteristic of Murray’s historic mule-headedness and also his years-long quest to overcome the indignities of injury and bodily collapse.

Famously, Murray underwent a hip “resurfacing” procedure in 2019, in which part of his right hip was replaced with a metal implant. Before his hip, essentially, gave out, Murray had briefly reached number one in the world in 2016, an especially remarkable feat in the era of Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic. Murray’s determination to train and compete after a hip replacement, and his success in pushing top players like Stefanos Tsitsipas to the limit in memorable slam matches at Wimbledon and the US Open in the years after his surgery, have made him into a different kind of figure than athletes who achieve greatness with seemingly little effort.

Though Roger Federer has made a point of explaining that his “effortless” style was, in fact, the product of intensive training, and though he was ultimately forced to retire due to knee injuries that rendered him a shadow of himself at his peak, his enduring image is that of a peerlessly graceful and stylish player. He was beloved because he seemed like a god, a figure unlike the rest of us. Even at his most successful, Murray’s appeal lay in large part in the effort and toil that underpinned both his victories and defeats and that expressed itself in his playing style: he was at his best returning, getting to balls no one else could, tiring opponents out. After his hip replacement, Murray became an even more relatable figure: someone whose body would not do what he asked, who was frequently in pain (not only from his hip but from frequent groin injuries, now his back, and countless other niggles over the years), and who kept trying anyway.

It seems inconceivable to me that Andy Murray considers himself disabled. The idea may seem absurd: even while struggling with various body parts, in the wake of that crucial surgery, he has been capable of physical feats that regular people would never dream of. I also don’t know how these surgeries and chronic injuries will affect his body once he is no longer training to play professional tennis. Federer, who had back surgery and multiple knee surgeries in the final phase of his career, seems to my outsider’s eye to be enjoying the fruits of his former labors to the fullest extent: jumping off boats, skiing down mountains, showing up at pop concerts at which he’s invited on stage. If he is dealing with persistent physical concerns, which he may well be, he doesn’t show it, and they don’t seem to be preventing him from enjoying his retirement to the fullest.

Other athletes, though, endure more complex and lasting injuries and chronic conditions as they age and approach retirement. Murray, Juan Martin del Potro, and especially Rafael Nadal have brutalized their bodies in the name of one last chance to compete and perhaps win. (Two years ago, Nadal’s doctors numbed his foot so that he could not feel the pain of a deteriorating bone, allowing him to win one final Roland Garros title. The bone, one presumes, continues to deteriorate.) As a viewer, though I have never been athletic or even very physically fit, I see some of my own frustrations and limitations in these players, who do not want to let their careers go. This past week, Andy Murray desperately wanted to play one final singles match, which he would inevitably have lost, to provide him with something — what? — some form of closure. But closure, as I’ve learned myself, and as so many other people whose bodies have taken away their jobs and passions, doesn’t really exist.

Subscribe if you like what you're reading.

This brings me to Emma Raducanu, Britain’s twenty-one-year-old major champion, who has herself been plagued with chronic medical issues despite her young age. Since winning the US Open in 2021, she has struggled to gain a foothold in her sport, repeatedly sidelined by injury. A year ago, she had surgery on both wrists — a particularly perilous area for tennis players — and an ankle. Since then, she’s made tentative progress, with wins at the Billie Jean King Cup (a national competition for women’s players) and a competitive loss to world number one Iga Swiatek on Swiatek’s preferred surface, clay.

This Wimbledon, Raducanu has suddenly started playing serious tennis again, perhaps inspired by the home crowd, perhaps by her comfort on the grass, perhaps by some other private factor the rest of us will never know. She also agreed to play mixed doubles with Murray, a match scheduled for yesterday that would have been a final send-off for him, in the wake of his match with his brother, after which Wimbledon held a ceremony with around a dozen current and former players in attendance, and brought back now-retired but legendary broadcaster Sue Barker to talk to Murray before the emotional Centre Court crowd.

Yesterday, Raducanu pulled out of the mixed doubles, citing stiffness and soreness in her wrist. The match’s scheduled time, late in the evening, was also a contributing factor, given that she has a singles match this afternoon (set to start shortly, as I type). Immediately, critics on social media exploded into a furor over this decision; the BBC announced that she had “ended Murray’s Wimbledon career”; Murray’s camp put out that he was “very disappointed”; and Judy Murray, his mother and a professional coach and advocate for women’s and girl’s tennis, posted on X and Instagram about the situation, calling it “astonishing” and sharing a post in which Serena Williams was quoted (some years ago) about what an honor it was to play doubles with Murray.

Inevitably, I saw this fiasco through the lens of disability; though, again, I’m sure that Murray and Raducanu don’t consider themselves disabled — and Raducanu, given her youth and the fluctuating state of her body, may not really fall into that category. I am not trying to diagnose anyone with anything, of course, or force people I don’t know into an identity group (though I should also note that I don’t believe that being disabled should be the source of shame, even for professional athletes). But as this situation grew and worsened yesterday, I thought more about Murray and what he wanted out of this experience: closure, as I said, which is a myth. A last taste of competition, which he won’t get to experience in the same way as a civilian. But that, too, is a kind of fantasy, because he was not well enough to compete seriously, and Raducanu had never played doubles before and was not likely to perform well enough to win the match of her own steam.

Last night, on The Tennis Podcast, journalist and pundit Matt Roberts pointed out that Murray had not expected his match with Jamie to be his last match at Wimbledon, and so something had been “taken away” from him by Raducanu’s decision to withdraw. Yet Raducanu did not take away Murray’s career: his body did. Every athlete’s body eventually fails, just as every human being’s body eventually fails, some earlier and more dramatically than others. I am not an athlete, but my career has effectively ended prematurely due to my chronic illnesses, and like Murray and all the other players who have and will have to learn to live without tennis, I have had to learn to live without work. Work, ideally, brings purpose to our lives. Even if we do not always love our jobs, and even if we have to carry out mundane tasks we find boring, as long as our jobs are not dangerous or cruelly demeaning, having this sense of purpose and earning a living from that purpose animate our lives. But eventually, our bodies give up, and when that happens, we cannot bargain our way out of injury, illness, or disability to keep working. Work is, of course, not the only thing taken away by illness and disability. Our passions are curtailed, too, as Murray is currently experiencing.

Disability, chronic illness, and chronic injury force us to make difficult decisions: about what to prioritize and when to simply give up. Both Raducanu and Murray have had to make these decisions this week, Raducanu to prioritize her health and her chances in the singles tournament, and Murray to give up his career. But he’s also tried, in some way, to not give up — to not quit — to travel back in time to the days when he was not in so much pain and when his body had not betrayed him. Without anyone exactly planning for it, this canceled mixed doubles match has perfectly illustrated what Murray knows but doesn’t seem to quite want to know: that it is over, that his body has won. Raducanu’s body has not won yet but she has clearly learned to respect its threats and demands. This is smarter than simply choosing to play through pain, because it’s what athletes are “supposed” to do.

Like Murray — and no doubt like Raducanu — I wish that I were healthy, that I could walk out of my front door today and take a long walk in the park that’s only a few blocks from my door. Instead, I can’t get there on my own, and merely writing this has exhausted me. Am I proud? I am proud of surviving and of learning how to exist when so many of the pleasures and distractions of life have been taken away from me. I am proud of not feeling (much) shame. I don’t love my illness, my condition; but I accept the facts of my existence. One day, I hope, Andy Murray will, too.