Årstas egen Banksy

Jag är övertygad om att vår busshållplats är ett tillhåll för en eller flera wannabe-Banksys. Små skyltar och klistermärken skvallrar om att hållplats Sköntorpsplan för buss 160 frekventeras av gatukonstaspiranter. Häromdagen dök ovan badattiralj upp, som med sin knasiga design och uppblåsthet skvallrar om att det knappast är något som en barnfamilj på väg till en badplats har glömt kvar.

Den filosofiska recensionen av tre nyutkomna översättningar av Ludwig Wittgensteins Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus avslutas glädjande nog med en konsumentrekommendation:

That said, I strongly recommend that anglophone students of this work get hold of [Michael] Beaney’s and [Alexander] Booth’s translations too – and maybe [Damion] Searls’s, but they will need to treat the last with a great deal of caution.

En av sommarens största läsupplevelser var Hisham Matars My Friends. En bit in i den hajar jag till inför följande stycke:

It was a sunny day. He suggested we walk to the Jardin sauvage Saint-Vincent, a small park behind the Sacré-Coeur in Montmartre.

…och lite senare:

He proceeded to tell me about the garden, how it was part of an old piece of fallow land, that the trees, plants, and flowers were all self-sown. “A little wild meadow locked inside the city.”

Jag kom naturligtvis att tänka på min halvvakna dröm förra året:

Benjamin hade först svårt att hitta platsen – det tog veckor att lokalisera den bakom en anonym port, innanför vilken en frodig och vild natur öppnade sig …

Ett tecken?

Rachel Kushners Creation Lake finns nu att läsa och den är recenserad och hon är intervjuad. Det går inte att motstå en berättelse på spiontema som kombinerar franska eko-terrorister som bor i grottor med neandertal-genetik, om jag har förstått det rätt.

På nåt vis kommer jag att tänka på matematikern Alexander Grothendieck, vars märkliga öde nyligen uppmärksammades i en fascinerande artikel i The Guardian, där journalisten Phil Hoad bl.a. rest till södra Frankrike för att besöka och prata med Grothendiecks barn. (En artikel i The New Yorker för ett par år sedan väckte ett intresse, mest språkligt då). Grothendieck startade ett kollektiv och en ekologisk och teknikkritisk think tank – Survivre [et vivre] – men det gick så där med samlevandet (från NYer-artikeln):

Grothendieck also envisaged a commune, in a house with at least twelve rooms, which would have “the warmth of a family environment.” In 1972, this idea became a reality, in the town of Châtenay-Malabry. He began dating a mathematician, Justine Skalba, whom he had met at a talk at Rutgers; soon afterward, she agreed to leave her studies and follow him. The commune, founded with friends, started with only four people, but others came and went, and sometimes meetings were held on Survivre issues which attracted up to a hundred people. Grothendieck sold sea salt and organic vegetables, but others called him “the bank,” because he was the source of all cash. The commune fell apart within a year.

Andra säregna franska gubbar som dyker upp i södra Frankrike är (anti-)psykiatrikern Fernand Deligny, som “experimenterade” med att förstå och behandla autistiska barn i något slags kollektiv på landet:

Beginning in the 1950s, Deligny conducted a series of collectively run residential programs — he called them “attempts” (or tentatives, in French) — for children and adolescents with autism and other disabilities who would have otherwise spent their lives institutionalized in state-run psychiatric asylums. After settling outside of Monoblet in the shadow of the Cévennes Mountains in southern France, Deligny and his collaborators developed novel methods for living and working with young people determined to be “outside of speech” (hors de parole).

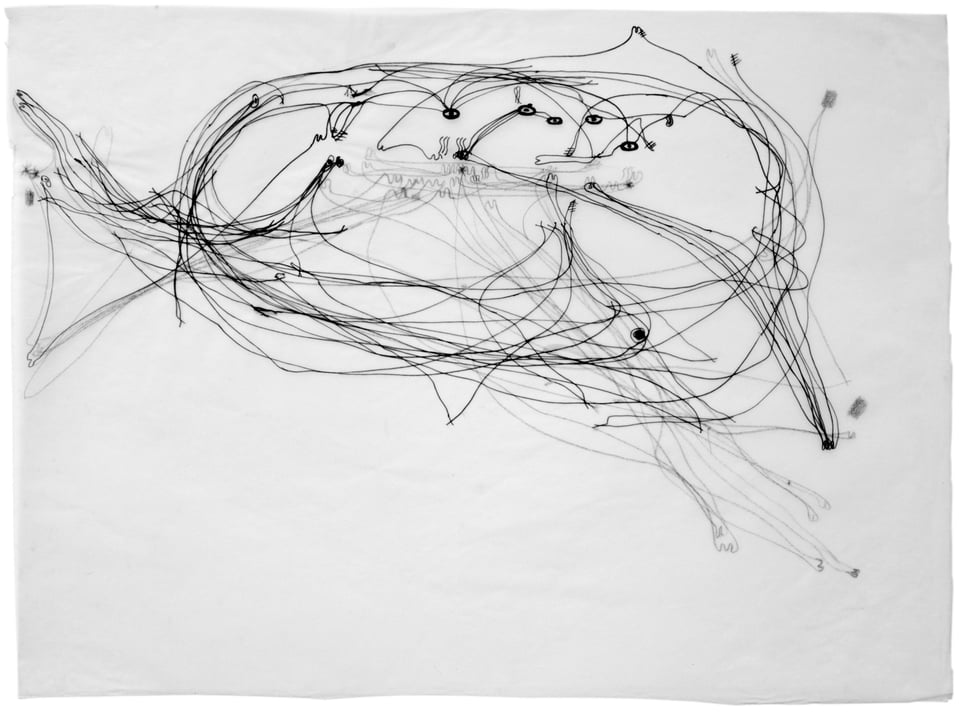

När man läser om deras metod att följa och kartlägga hur barnen rör sig i naturen så är det med blandade känslor av creepiness och fascination:

Abandoning the politically charged atmosphere of La Borde for the desolate Cévennes region, Deligny and his colleagues continued their singular pursuit of “the network as a mode of being” — one that would be far less concerned with interpreting behavior and experience according to the hidden intentions and secret desires of individual human subjects, and more focused on “tracing” the trajectories, detours, and wander lines that compose a given social milieu. It was here that Deligny consummated his longstanding preoccupation with mapping the gestures, movements, and trajectories of the autistics living within his networks. He first experimented with cartographic tracing in the late-1960s in collaboration with a young militant filmmaker, Jacques Lin, who joined the group’s small desert encampment. Deligny, Lin, and their collaborators began to follow their autistic counterparts as they made their way through the Cévennes’s rocky terrain, making rudimentary line drawings to indicate their direction of movement across the rural encampment and into surrounding wilderness.

(Båda citaten från en artikel i Los Angeles Review of Books i samband med att några av Delignys texter utkommit på engelska som The Arachnean and Other Texts.)

Här en karta där barnens vandringar ritades:

Södra Frankrike verkar vara fertil mark för anticivilisatoriska grupperingar och vi får väl se hur det skildras i Kushners roman – kan knappt vänta!

Det var ett tag sedan jag missiverade, men har tänkt att jag skulle vilja ta upp det lite mer stadigt.

Jag registrerade zibald.one häromdagen och tänker att jag ska göra något av det i framtiden. Wikipedia:

A zibaldone (plural zibaldoni) is an Italian vernacular commonplace book or notebook containing a wide variety of vernacular texts, copied into a small or medium-format paper codex by citizens in late-medieval and Renaissance Italian city-states.