Félix González-Torres at the NPG

This post is not, strictly speaking, about my PhD studies - but I did fieldwork at the National Portrait Gallery, and Félix González-Torres is one of my favorite artists, so I hope you’ll forgive the use of this venue to share my visit to “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return” at NPG.

I’ve been wanting to go for months, but the exhibition opened the day after my own museum opened a new exhibit, and things stayed hectic after that. Now that I’m freelancing as a consultant, I have the time to attend, and I will probably go at least once more before it closes in July. This post is a journey through art; if you’re only interested in my work for deaf friendly museums, feel free to skip reading this - but if you’d like a non-art historian’s view of art, please enjoy!

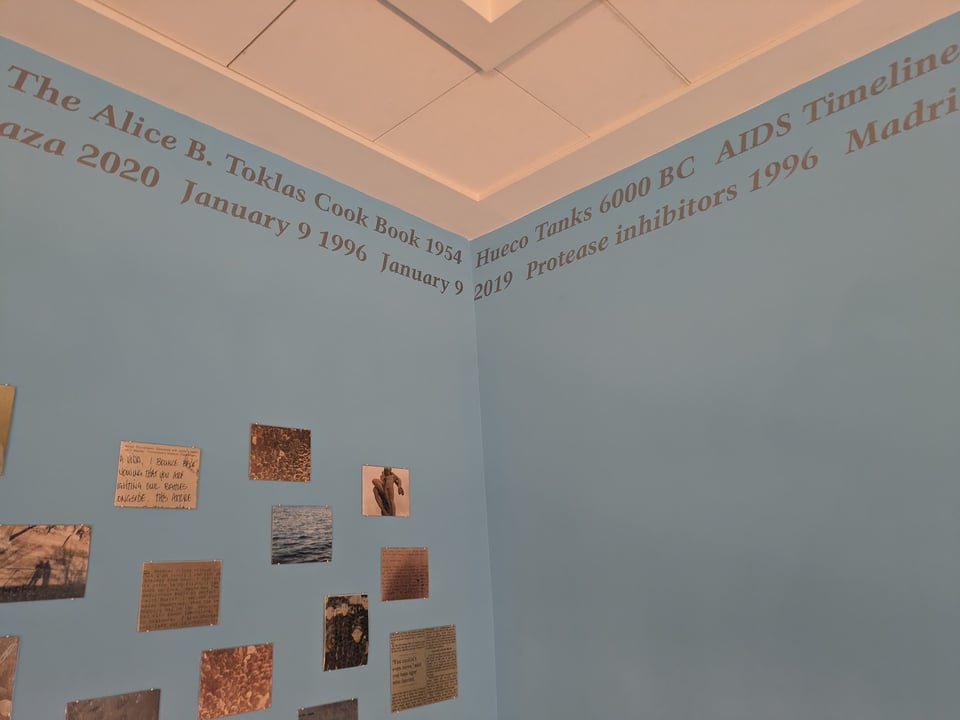

I love González-Torres’s works because they are so mutable. The word portrait above has changed dozens of times since its first showing in December 1989; these changes are the core of his work, and that the viewer ponders each change and each meaning is the purpose of his art. In this case, what I notice is that even in countries where English is not the native language, the work is always displayed predominantly in English. Pondering the reason for this is part of González-Torres’s mission - to examine the whys and hows of curatorial choices.

Also on display at NPG was Untitled (Portrait of Robert Vifian), which is genuinely evocative of the genre of word portraiture. Vifian is a Vietnamese chef, and while the work still varies with each installation, you can clearly read in its variations the story of the man. That Vifian outlived González-Torres does not matter - indeed, the artwork continues to do its creator’s intention even after his death, because its subject lives on. That is the brilliance of González-Torres’s style, that is why I love his work.

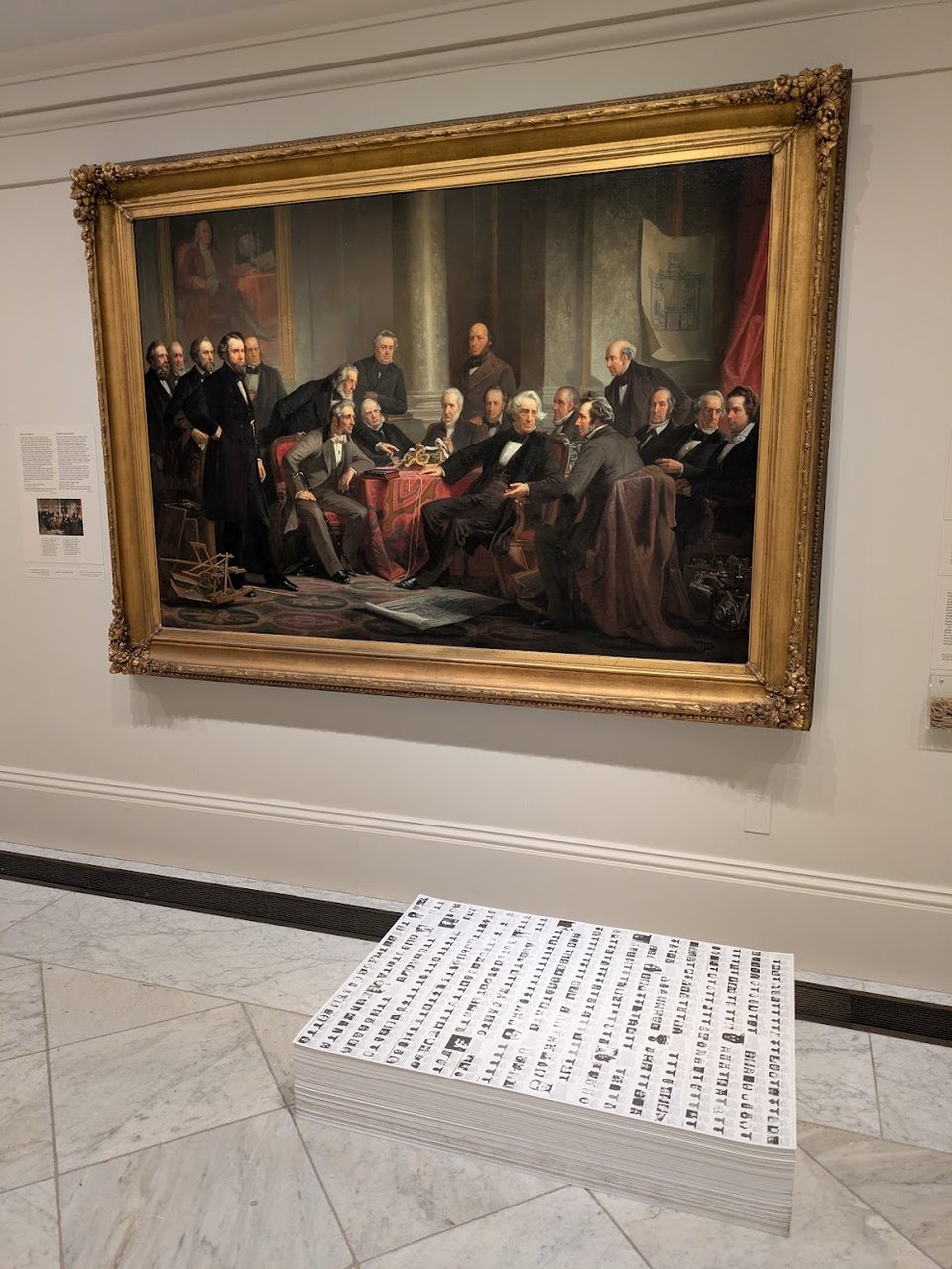

A clever juxtaposition by NPG - the advancement offered by Men of Progress, full of inventors, and Untitled (Death By Gun), full of 464 people who died of gun violence in one week in 1989, and what they might have invented now being lost to us.

NPG had several other Paper Stacks works in this show. Each was accompanied by a box of rubber bands, because you are meant to take a sheet home - I didn’t on this visit, because I had other stops to make in my day, and a big poster tube wasn’t conducive to my journeys. I hope to go back and take a sheet from Untitled (Death by Gun), though, or perhaps Untitled (Passport) - the latter is more my speed for keeping in my world, but neither is terribly easy to display.

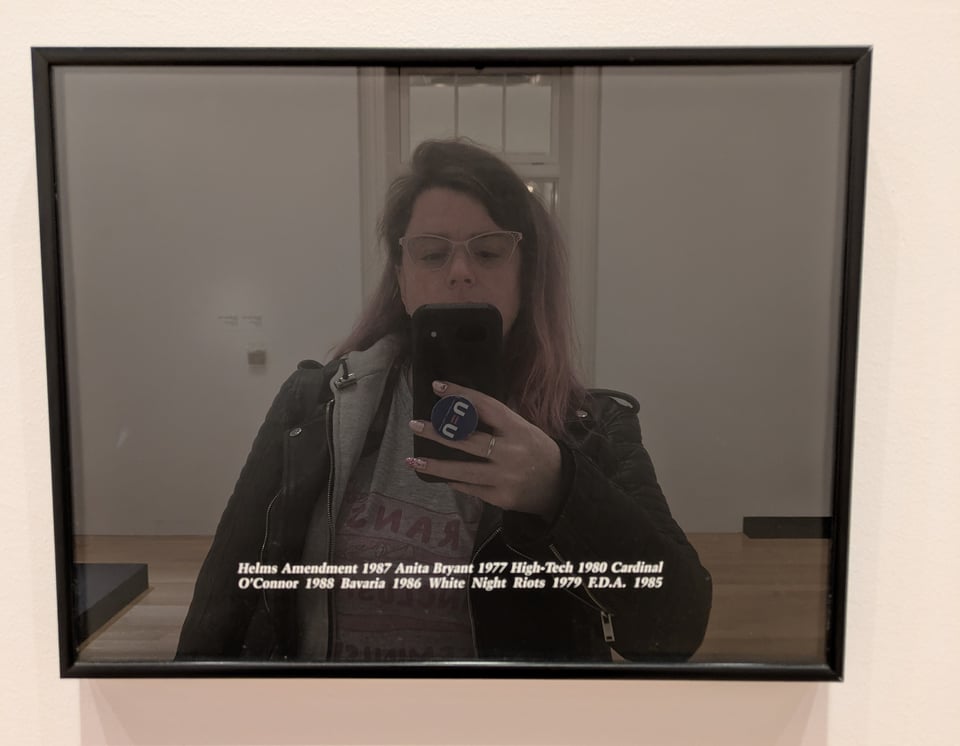

This is not one of his Mirror works. They had one - Untitled (Fear) was on display - but this is just a framed photostat work. Still, like the Mirrors, you are confronted with your own image as you view it. I normally try to avoid my own reflection when taking pictures, but that didn’t feel like the point here. This art demands, like so much of González-Torres’s art, that the viewer become part of the work. So here I am, in my Trans Inclusive Feminism Forever t-shirt and my leather jacket, my hair slightly mussed and my U=U Popsocket askew - part of his work.

|  |

|  |

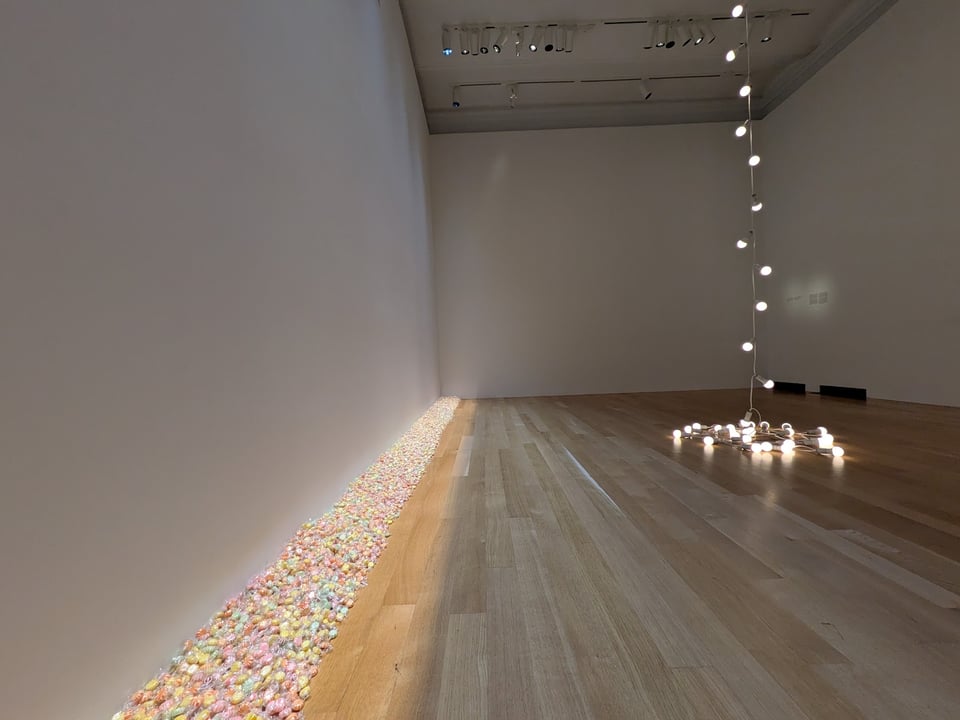

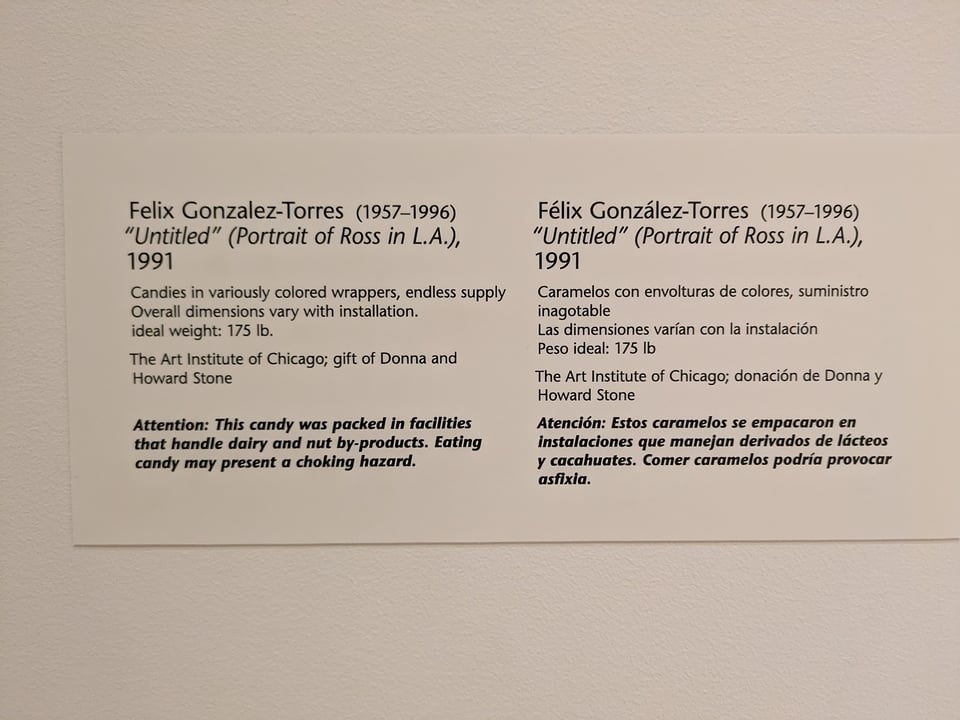

This is my favorite Félix González-Torres work. Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991) is probably his most famous - certainly of his Candy Works, which require museums to allow visitors to take the candies; most museums also replenish them regularly to maintain the work’s “ideal weight.” In the case of this piece, the ideal weight is 175 pounds - the weight of Ross Laycock, the artist’s partner, when he was healthy. In this case, taking candies represents the wasting syndrome common to HIV patients - as visitors take them, Ross gets thinner and weaker; he died of AIDS on January 24, 1991.

I am puzzled by the curatorial choice to choose variously colored candies in clear wrappers, rather than “candies in variously colored wrappers” as instructed by the artist - and even as written on the label at NPG. This creates a lighter, brighter version of this work than I am used to - it’s not bad, just puzzling. I also note that the label includes an allergy warning, which I assume was not part of the label at its original installation.

I found the piece’s juxtaposition with Untitled (Leaves of Grass), a light string work from 1993, quite interesting. This arrangement of the light string feels like it is falling, pooling on the floor as though someone has collapsed in a heap. Is that so different from the metaphorical experience of someone’s journey through illness during the AIDS epidemic? As bright as the lights and candies are, they both feel like a story of death to me.

I chose to take two candies from Ross today. The pink one I chose because it is my favorite color, and I am going to keep it in my store of precious things; it will be my souvenir from this show (unless I pick up one of the publications when they become available). I chose the yellow one to eat in the gallery, because I was curious if it was really lemon flavored, or if it was just a colorful peppermint. It was indeed lemon, which I found curious in thinking about the tartness of AIDS itself, its biting way of destroying lives when the work was created. (It took González-Torres, too, in 1996, at age 38.)

Another curatorial decision here - the artist’s instructions are that this piece is made of white mint candies in clear wrappers, and that is what is written on the wall label. But these candies are vanilla flavored, of a light taffy texture, in translucent white wax paper wrappers. In this case, the substitution feels almost like a statement on the father pictured - that he was a soft and sweet person, rather than a hard and acidic person. There’s an interesting photo at the link above depicting art handlers transferring pieces of this work, if you’re curious how the Candy Works are managed; you’ll also note that not all installations have been white mint candies in clear wrappers, either. As a final note, while this looks like a hefty pile, this was the side opposite the door. The side nearer the door had a good dent out of it from people picking up candies but not circling the piece; I also found a taffy from Dad among the hard candies in Ross in L.A.

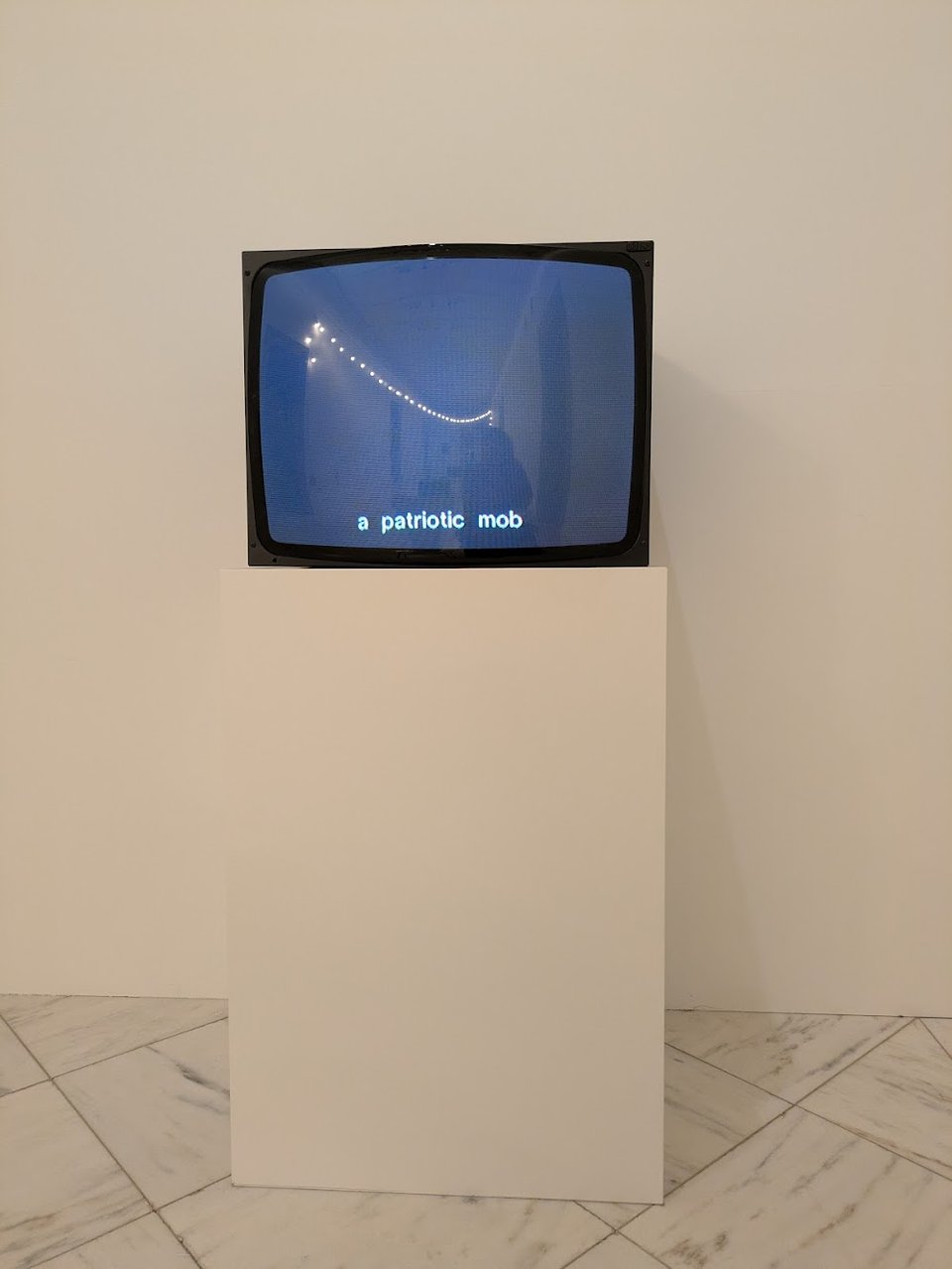

González-Torres’s only video work, Untitled (A Portrait) spoke to me less as a coherent image and more as an assemblage of thoughts. I took pictures of several screens, but “a patriotic mob” stuck with me the most given the cultural milieu in which I am seeing this exhibition, just days before and a couple of miles away from the next presidential inauguration. Beyond the video itself, though, I also see a hazy reflection of myself watching the television, and a clear view of another light string piece. So the image on the screen is not just the words, but it is also the environment in which the words are being presented - here, a patriotic mob gathered in the Second Floor North gallery, among the visitors and artworks.

I cannot tell you much about art history as a discipline, I did not study it as part of my museum studies education. But I love Félix González-Torres’s work, and I hope telling you about it has sparked your curiosity. I think he would also be fine if it sparked confusion, disdain, hunger, or other feelings. That’s what his work is, to me - it’s a way to engage, to experience, and to feel art.

Until next time,