Hit and Miss #1: Earthworming

Hia! Thanks for joining me. I really appreciate you yielding some portion of your inbox and your day to me. Let’s dive in.

An update on my life

I’m writing this at the end of a pretty peaceful day—a rarity for me in the last month or so. August saw me visiting BC with my family for two weeks, flying back to Toronto, hopping on a train to Montréal less than twelve hours later, speaking at WordCamp Montréal, and then moving apartments. It also saw me crashing, hard, after those crazy weeks. All the experiences were worthwhile (BC is really something—something nice—and visiting with friends in Montréal was lovely as always), but they certainly took their toll. I watched some good movies during those two weeks of crash, though.

I’m now, happily, back in Ottawa. I’m figuring out where I want to devote my energies. I’ve seen how detrimental it can be to be spread too thin, but it’s also hard to know in advance how significant any obligation will be. While school is happily humming along, I’m bouncing between a few ideas for where I want to work for the next little while: I’m considering whether to keep freelancing, to pursue part-time work in something related to government and tech, to pursue something a bit different for me like a retail job, or to pursue university research. These things could be combined, but finding the right mix is tricky.

The bright side of moving: reshelving

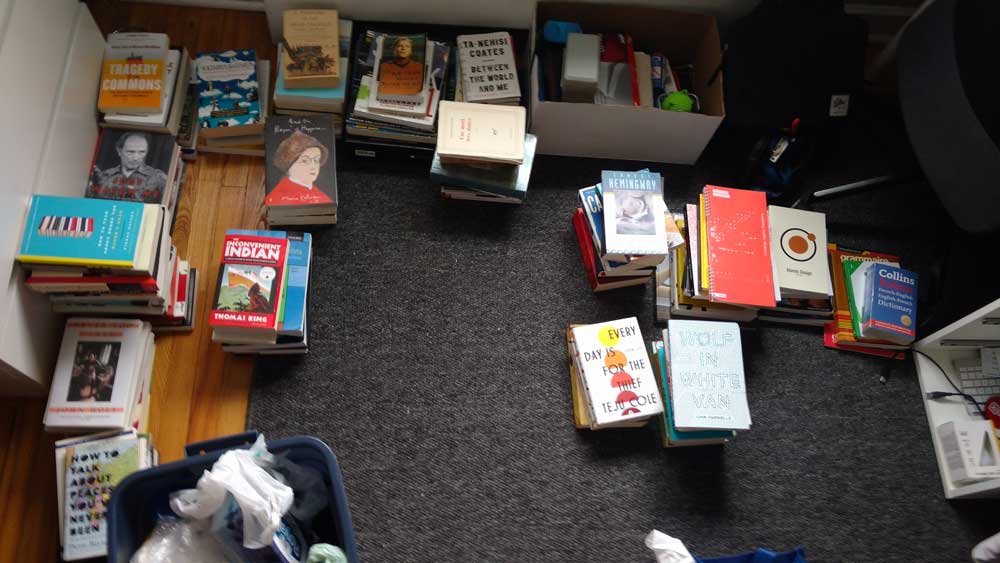

Unpacking, stacking, and sorting the books

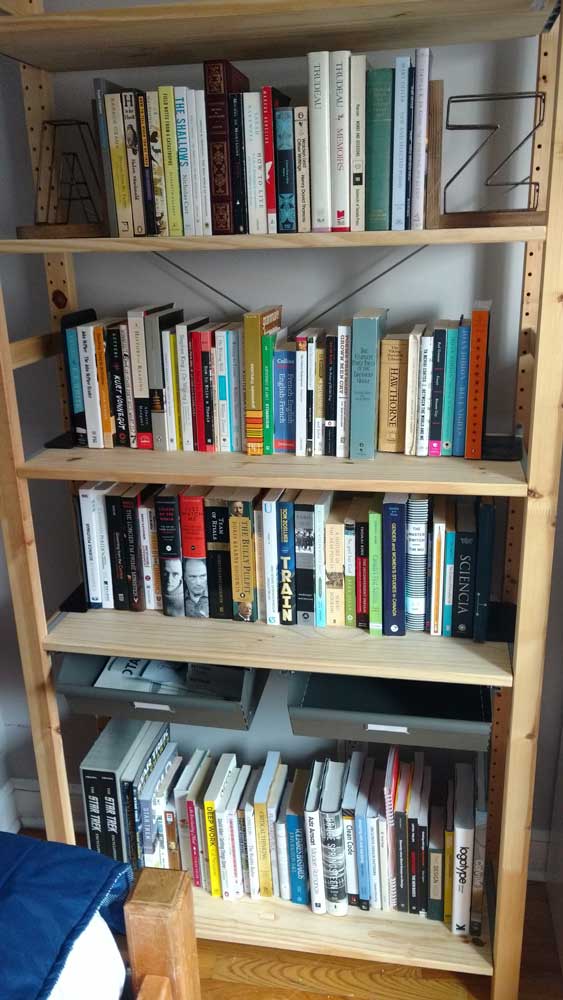

The books loaded onto the main shelves

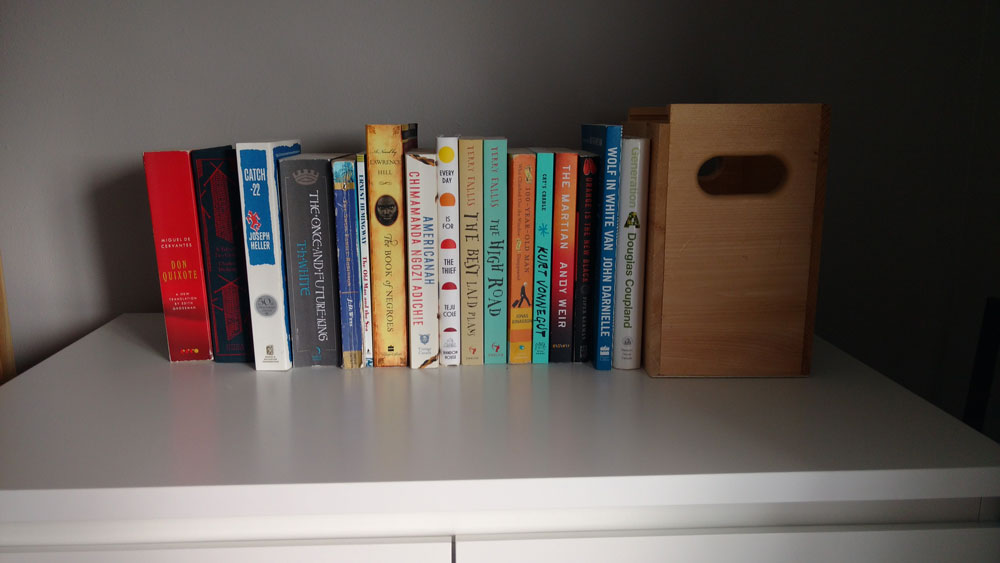

The overflow fiction section, occupying the top of my dresser

I’d like to talk for a bit about my books.

On the whole, moving was fine. Everything got where it needed to. I lugged a blue plastic container twenty times between my previous and current apartments, slowly bringing over the smaller detritus of the last year of my life. (My lovely parents drove over the larger items—thanks Mom and Dad!) Several of these boxes contained books. In all, I moved here with 130 books. Since moving and writing this letter (one week), I’m now at 136 books. (I’ve “read” about 68 of them, though I don’t believe a book is ever actually read.)

I love books.

I believe strongly that a personal library is a reflection of its owner. What exactly it reflects is known only to the person who assembles it, but looking at a person’s private library is enlightening. My library indicates my past, present, and (desired) future selves. Alberto Manguel writes that “we enjoy dreaming up a library that reflects every one of our interests and every one of our foibles—a library that, in its variety and complexity, fully reflects the reader we are.” Such a library is “an assembly of titles that, practically and symbolically, serves [to define us].” (These are from “The Library as Identity” in The Library at Night. If you stay with my writings, you’ll hear much more about Manguel.) Mandy Brown, another of my favourite writers, puts in words my own thoughts on the personal library:

The best library contains both books you have read, and books you have not. The latter should grow in proportion as the library expands. A working library is as much a place for the possible as it is a record of the past.

A place for the possible, indeed.

How to Tell When You’re Tired

One of the best books I read this summer was How to Tell When You’re Tired, by Reg Theriault. His book is packed with insights on working. He certainly has the experience to be an authority on it—Theriault was a longshoreman on the San Francisco waterfront for thirty years. The book is packed with history, literature, and anecdotes.

Some of Theriault’s major themes: we must respect workers (of all kinds); work is social in nature (this is one of the non-economic costs associated with the cuts automation inevitably brings, the loss of work as a social environment); and the need to “give everyone hope for the future.”

That last theme is worth elaborating. In the section the quotation is from, Theriault discusses providing paths toward meaningful advancement, even if that’s outside of management. The technology industry certainly grapples with this problem. How can you advance as a developer or a designer if you don’t want to become a manager? Theriault points out that, quite simply, “Everyone cannot be a boss; there are not that many openings.” Finding ways to reward people for their service beyond a move up the org chart is essential to caring for the people who work for you.

The other way I think this theme develops is exemplified with this quotation:

If retirement is what you are mainly working toward, then you are living a mistake, serving out a jail term, so to speak, waiting for release. … Vacation in the summer is not even a parole, because you have to come back.

Hope for the future doesn’t come just from hope that you’ll get more money or more authority or more of whatever compensation you seek from your job. It also comes from hope that the future of tomorrow, of next week, of next month will continue to yield a job that’s meaningful and worth showing up for. How do you provide this? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ (I can’t say for certain, but it likely has something to do with making a meaningful impact on the lives of others and being able to observe that impact.)

There’ll be more from this handy little book sometime in the future. If you can’t wait, I highly recommend grabbing your own copy and enjoying it yourself. (I read it in June, sitting in Ottawa’s Confederation Park and on the banks of the Rideau Canal.)

Digging in and putting out roots

I’ve been thinking a lot about local community: how to support your local community (communities), how community can hold so many distinct meanings and take a multitude of forms, and how to cultivate communities. I don’t have answers for most of these thoughts, though I reckon that the latter, about cultivating communities, depends very much on context. I’m still playing through different perspectives on these issues—if you have any thoughts on any of them, I’d love to hear them.

The title of this section is quite intentional. My thinking on this issue has intensified thanks to seeing Look and See at Princess Cinemas (ahh, the Original Princess) while I was in Waterloo last week. Look and See is a documentary profiling the life and works of Wendell Berry, the American farmer and writer.

I don’t know much about Berry, but I like what he said in the documentary, and I like how he said it. One point he made really stuck with me. In talking about the small communities throughout the rural United States, communities which used to thrive but may now be dead due to the loss of family farms, Berry says that “no place is nowhere.” There are important histories all around us, and we ought to accord them more respect. No place is nowhere. Nice.

A closing word, from Ursula M. Franklin

In 1989, Ursula M. Franklin, then a physicist and professor at the University of Toronto, delivered the CBC Massey lectures. (Side note: I love published collections of spoken words.) Her series explores the intersection of technology and life. The subject matter may seem specific, but it’s relevant for just about anybody. We had all ought to think more critically about the technology we let into our lives, for it’s no passive entity. It is an active force that reshapes us even as we use it to reshape the world around us.

One of Franklin’s persistent points is that process informs culture. As we shifted to “prescriptive technologies,” ones which broke production into a series of isolated and repetitive steps, our broader culture shifted toward a “compliance culture,” one focused on collective adherence to rules and regulations. This shift was a rational response to the need for conformity in production, but just because it’s rational doesn’t mean it’s right.

The title of this letter, “Earthworming,” is a reference to Franklin’s sixth lecture. In it, she shared “Franklin’s earthworm theory of social change”:

Social change will not come to us like an avalanche down the mountain. Social change will come through seeds growing in well prepared soil and it is we, like the earthworms, who prepare the soil. We also seed thoughts and knowledge and concern. We realize there are no guarantees as to what will come up. Yet we do know that without the seeds and the prepared soil nothing will grow at all. … What is needed is a lot more earthworming.

I have never seen “earthworm” used as a verb before, but of course. I hope this newsletter will contribute in some small way to preparing the soil. May we all be better earthworms.

Sent from Ottawa, Ontario.