Online, Asynchronous Schema Change in F1

That's right, we're back to the world of databases. Not because I haven't been screwing around with my dinky little compiler but because I was starting to get embarrassed about how little I've been writing about databases which is ostensibly what you signed up for. This week I thought we'd revisit an old classic: Online, Asynchronous Schema Change in F1.

F1 is the original name for the SQL layer on top of Spanner, before it was folded into Spanner itself, so you can read it as "schema changes in Spanner." I assume they don't do it this way any more (although they might! I have no insight into it), but I always thought this paper was a really lovely solution to a problem that they manage to specify really nicely.

Some background to the problem they are trying to solve, with my simplified perspective as someone more familiar with a prominent Spanner clone. The underlying storage is all key-value based, so you might think of it as just like, raw, untyped bytes. The SQL layer on top creates structure out of that via the schema. I think of the schema in this setting as sort of a lens that you peer through to see the row structure of what is actually a bunch of bytes underneath.

The schema is responsible for translating logical SQL operations into physical operations on the KV data. That is, it might turn:

CREATE TABLE xy (x INT PRIMARY KEY, y int);

INSERT INTO xy VALUES (1, 2), (3, 4)

into

xy_primary.Put(1.bytes(), 2.bytes())

xy_primary.Put(3.bytes(), 4.bytes())

Since x is the key in this table.

If we had a secondary index, say on y, we'd have to create additional writes to that secondary index that use y as the key and x as the value (assuming we've got a UNIQUE index):

xy_secondary.Put(2.bytes(), 1.bytes())

xy_secondary.Put(4.bytes(), 3.bytes())

Now let's consider the problem of adding a secondary index to an existing database, first, sticking to a single-node database.

Actually building the secondary index takes some non-trivial amount of time, because we need to read all of the primary index and concoct writes to construct the secondary index from them. In the meantime, more writes might come in, and our initial scan might miss out on them. So, we have two options:

- After we finish our initial scan, scan any of the new mutations and also do index mutations for them (after which point we might have to repeat this process, until we eventually just block writes for the duration), or

- have any writes that occur during the index build also induce index mutations as they're written.

I suspect option 1 is more popular, but option 2 is what this paper is about, so let's think about this. To do a schema change where we add a secondary index, we:

- Begin assigning any new writes the new schema, so any inserts or deletions will induce a secondary index write,

- scan the entire data and build the secondary index (note we might re-process rows that have been processed by a write, which is fine),

- we're done now. Mark the index as available for reads.

This is great in a single node system, where step (1) can be done atomically, but in a distributed system where there are multiple nodes all using the schema at the same time, we can't guarantee that all of the nodes will swap over to the new schema at exactly the same time. So there will necessarily be points in time where two nodes are looking at data with a different perspective:

Is this a problem? Yes!

Say node 1 has this schema:

CREATE TABLE xy (

x INT PRIMARY KEY,

y INT,

INDEX (y)

)

and does this insert:

INSERT INTO xy VALUES (1, 2)

This will induce these key-value writes:

xy_primary.Put(1, 2)

xy_secondary.Put(2, 1)

Now, at the same time, node 2 has this (old) schema:

CREATE TABLE xy (

x INT PRIMARY KEY,

y INT

)

and does this deletion:

DELETE FROM xy WHERE x = 1

This will induce these key-value writes:

xy_primary.Delete(1)

and leave the secondary index write that the first node performed orphaned, leading to corrupt data.

We talked about this kind of atomic state transition in My First Distributed System, which I think puts forward a useful mental model for this sort of thing: in a distributed system we can't move all the participants through state transitions at exactly the same pace; it's not even necessarily clear what it would mean, since conceptually they all have their own timelines.

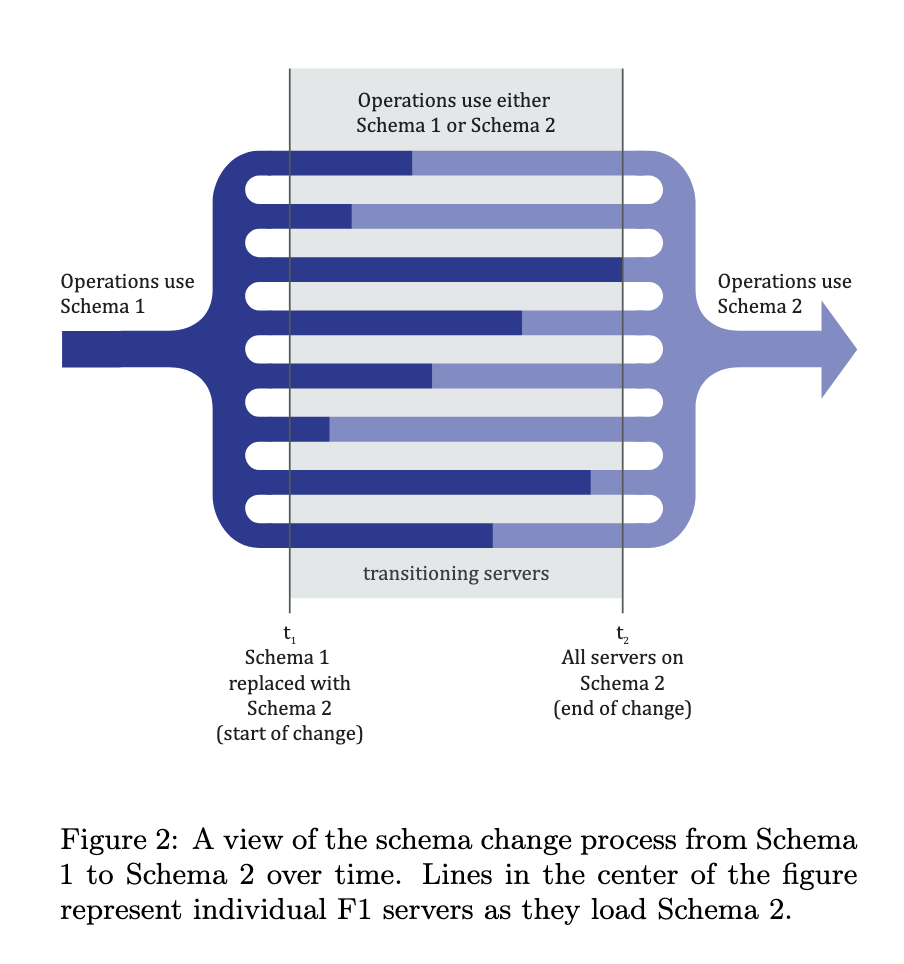

What we can guarantee is that the participants move through in lockstep: move from state A to state B, and then wait until everyone else moves to state B before you move to state C. In this way, we can bound the set of active states in the system to only two.

There's this nice diagram from the paper the illustrates this situation:

Immediately, this doesn't seem to help us, since as we saw, the two states, "no index" and "index" are "incompatible," in the sense that their coexistence can lead to data corruption. The clever insight of the F1 team is that we can invent new states in between these two.

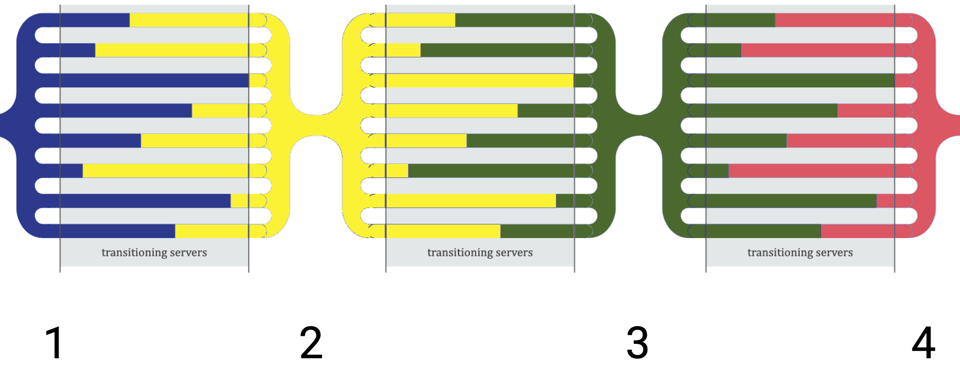

In F1, when an index is added, there are actually four states:

- no index,

- delete-only index,

- write-only index,

- completed index.

Once all the nodes are in the "write-only index" state, we do the build for the old rows.

Carefully checking these states will show that even though 1 and 4, as we saw, are incompatible (produce corrupted data), 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 3 and 4 actually are compatible (the paper provides a more rigorous definition of "compatible"), and will not produce corrupted data if they coexist. So by chaining these state transitions, we can safely add an index:

I think this is a cool trick, where you invent new states that don't actually correspond to something meaningful to the user, but serve to bridge a gap between other states that they do care about.

Check out the paper itself if you want a more thorough treatment of these ideas but I think this is the heart of it: the lock-step state transitions that limit the set of active states to size two.

Add a comment: