Mark Join

I was going through the list of CIDR papers this year and looking for ones that were relevant to my interests. If you're not familiar with CIDR as an institution, it's basically the "short, kind of kooky" database papers conference. You're more likely to find things that are a little looser, a little more speculative, a little more off the wall, and a little more self-contained.

I enjoyed On the Vexing Difficulty of Evaluating IN Predicates, which is relevant to my interests as far as "surprising SQL behaviour" goes.

This in particular made me laugh, though:

Me not knowing anything about the legal particulars, but generally understanding CedarDB to be a commercial form of Umbra, I found this "shade" a little funny.

An IN predicate is, conceptually, just checking for set membership:

justin=# select 4 in (1, 2, 3, 4, 5);

?column?

----------

t

(1 row)

justin=# select 6 in (1, 2, 3, 4, 5);

?column?

----------

f

(1 row)

The difficulty they note arises from (as usual) the possible presence of NULL in the collections. Remember that in SQL, NULL is, allegedly, "we don't know what this value is." This is not applied in the most principled way, but in general it's relatively consistent. If we compare a value to NULL, we get NULL, because we can't know if they were equal or not. The uncertainty is infectious:

justin=# select 1 = null;

?column?

----------

(1 row)

(blank means NULL, in Postgres.)

And with PostgreSQL arrays,

justin=# select array[1] = array[null::int];

?column?

----------

f

(1 row)

Wait, what? Ah, well. whatever, I guess (this is actually a good design choice; having top-level NULL is complicated enough, and having to deal with multi-level NULLs, as we'll see, is a nightmare).

However, in some cases, we can actually deduce the outcome of an expression whose value we don't know; see

justin=# select true or null as ton, false and null as fan;

ton | fan

-----+-----

t | f

(1 row)

Which, you know, sort of makes sense. Even though we "don't know" what those NULLs are, there's no boolean value they could take on that would change the values of those expressions, so for =, we can determine non-NULL values for them.

I don't personally like this behaviour and I don't really think it stands up to much scrutiny. If NULL OR true is true, shouldn't you be able to argue that a = NULL OR a <> NULL should be true, and not NULL, then? Anyway. A battle that was lost before I was born.

This extends to IN: we can tell that 1 is definitely in (1, NULL, 3):

justin=# select 1 in (1, null, 3);

?column?

----------

t

(1 row)

But we can't tell whether 2 is:

justin=# select 2 in (1, null, 3);

?column?

----------

(1 row)

This naturally extends to tuples:

justin=# select (1, 2) in ((1, null), (null, 2));

?column?

----------

(1 row)

justin=# select (1, 2) in ((1, null), (null, 2), (1, 2));

?column?

----------

t

(1 row)

The observation made by this paper is that this is a deceptively hard thing to implement efficiently, and many databases simply do the wrong thing (at least according to the SQL spec):

DuckDB v1.3.2 (Ossivalis) 0b83e5d2f6

D select (1, 2) in ((1, 2));

┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ (main."row"(1, 2) IN (main."row"(1, 2))) │

│ boolean │

├──────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ true │

└──────────────────────────────────────────┘

D select (1, 2) in ((1, null));

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ (main."row"(1, 2) IN (main."row"(1, NULL))) │

│ boolean │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ false │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────┘

And of course these examples, where we use an explicit list literal, are just for demonstration; in reality we could have the right-hand side be a query that reads from a table or does some kind of arbitrary computation, such that we don't know fully the data at plan-time.

As they note, for something like IN, it's easy to tell when the answer should be true; it's true whenever the exact row you have appears in the right-hand side of the expression. The tricky thing is determining whether a given result should be NULL or false.

If the exact row doesn't appear, then it should be NULL if

One of the fun observations they make in this paper is that they can reduce the problem of finding orthogonal vectors to computing these sorts of IN queries, which guarantees (subject to your philosophical beliefs) that there exist some sorts of queries that require at least quadratic time. In an algorithms class, this would be reason to throw up your hands and say, "well, that's it! They cracked it."

This is query processing though! And we're not just interested in the theoretical minimum, but recognizing when the particulars of a given query allows us to compute it faster than that.

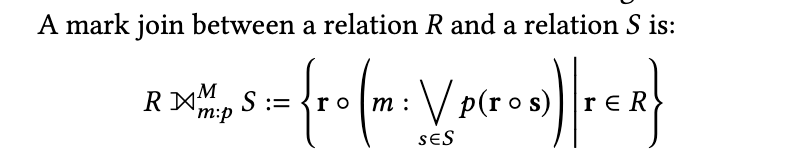

In the paper, they discuss a query primitive they call a "mark join" that they claim has good properties in this regard, where in many common cases that are computable in linear time, the algorithm delivers linear time performance, and only decays to quadratic time execution when it needs to. So, let's finish this issue out by discussing what "mark join" even is. If you want to follow along the paper for how they extend this to computing their INs, you should check out the paper itself. The definition they give is:

Which is, perhaps, a bit intimidating of a definition. But it's mostly the symbology that's confusing. Their prose description is:

In other words, a mark join computes the disjunction of the predicate

pon all rows ofSfor each row ofR. This disjunction is then added as a new attributemto the result.

So, we have a relation R, a relation S, and a predicate p. This is already starting to sound like a join; if we were to compute the inner join of R and S "on" p, we'd be finding all pairs of rows (r, s) for which p(r, s) is true. Recall that this has the property that it might completely remove rows from the result; if there is no s that makes p true for a given r, that r will not show up in the result at all. This is a problem for certain kinds of computations that we often want to do.

Here's a common thing we might want: for each customer, sum of the value of all of their orders. This is pretty easy to compute conceptually: for every customer, find all of their orders, and add up their value. We can join customer and orders to pair them up, and then aggregate the result:

SELECT c_id, SUM(o_value) FROM

(SELECT * FROM customer INNER JOIN orders ON c_id = o_cust_id)

GROUP BY c_id

Actually running this query, we can see a problem: we've thrown away a customer:

D select * from customer;

┌───────┐

│ c_id │

│ int32 │

├───────┤

│ 1 │

│ 2 │

│ 3 │

└───────┘

D select * from orders;

┌───────┬───────────┬─────────┐

│ o_id │ o_cust_id │ o_value │

│ int32 │ int32 │ int32 │

├───────┼───────────┼─────────┤

│ 1 │ 1 │ 10 │

│ 2 │ 1 │ 20 │

│ 3 │ 2 │ 30 │

└───────┴───────────┴─────────┘

D SELECT c_id, SUM(o_value) FROM

(SELECT * FROM customer INNER JOIN orders ON c_id = o_cust_id)

GROUP BY c_id;

┌───────┬──────────────┐

│ c_id │ sum(o_value) │

│ int32 │ int128 │

├───────┼──────────────┤

│ 1 │ 30 │

│ 2 │ 30 │

└───────┴──────────────┘

Semantically, there's no reason customer 3 shouldn't be present in this result, it's just that they have no orders. We generally solve this by switching to an outer join instead:

D SELECT c_id, COALESCE(SUM(o_value), 0) FROM

(SELECT * FROM customer LEFT OUTER JOIN orders ON c_id = o_cust_id)

GROUP BY c_id;

┌───────┬───────────────────────────┐

│ c_id │ COALESCE(sum(o_value), 0) │

│ int32 │ int128 │

├───────┼───────────────────────────┤

│ 1 │ 30 │

│ 2 │ 30 │

│ 3 │ 0 │

└───────┴───────────────────────────┘

The reason that customer 3 got dropped from our result set is that there were no rows in orders that make the predicate (c_id = o_cust_id) true.

This is precisely what the mark join is computing: it's telling us whether or not a given row would be dropped when doing a join with a given predicate. This comes up a lot (as they note) when doing decorrelation, which makes it a useful primitive.

In order to implement it efficiently, they decompose the predicates into components which need to take NULLs into consideration and components which don't (because they can prove statically from the shape of the query, for whatever reason, that those columns will never be NULL). Using these optimized implementations, they claim, you can implement IN efficiently in a lot of common cases.

Add a comment: