Inlining

This is the last NULL BITMAP of the year. If you read these with any regularity, sincerely, thanks for spending time with me every week.

Reflecting on the year, I have been a bit down about the future of programming culturally, with the advent of LLMs it feels like people are telling me that being interested in how things work and how best to think about things is a waste of time. That "no, no, we're automating the boring parts" refrain fills me with dread about which those people thought were the boring parts. And the constant sense that if I'm not programming that way I'm falling behind. And the idea that thinking about things in a way that isn't "scalable" and "good for LLMs" is a liability.

I'm trying to remind myself that thinking about things and thinking about how to think about things is something that nobody ever really does for like...profit. And I expect that none of you who read NULL BITMAP are reading it with the expectation of becoming more efficient at anything. I mean, probably the opposite is more likely.

That's just to say that I'm gonna do my best to continue to enjoy computers the way I want to, which is mostly reading old books about them and writing throwaway programs.

One thing you might hope about query planning is that the size of a query plan isn't too big relative to the size of the input query. We might make this precise by saying something like, if there's a sequence of query plans q1, q2, ..., and the output query plans P(q1), P(q2), ..., then we want the sequence len(P(q1))/len(q1), len(P(q2))/len(q2), ... to grow subexponentially.

Why would you want this? Oh, I dunno. It just seems like a desirable property. Perhaps in practice, you're not concerned about such things, but it would be nice to know that we don't have the risk of our plans exploding when we mechanically generate queries.

One optimization that's fairly nice to be able to do is inlining. Consider the following query:

SELECT 1-a FROM (SELECT 1 AS a)

What we really want to be able to do is to inline the 1 from the subselect into the parent select, so that we get

SELECT 1-1 FROM (SELECT 1 AS a);

->

SELECT 1-1;

->

SELECT 0;

A more substantial example that we need this for, that we might get from ORM-generated queries, is something like:

SELECT

CASE tag

WHEN 'xs' THEN v * v -- want to square things coming in from xs

ELSE THEN v

END

FROM (

SELECT 'xs' AS tag, x AS v FROM xs WHERE true -- generated by ORM

UNION ALL

SELECT 'ys' AS tag, y AS v FROM ys WHERE false -- generated by ORM

);

-> remove the empty union branch

SELECT

CASE tag

WHEN 'xs' THEN v*v

ELSE THEN v

END

FROM (

SELECT 'xs' AS tag, x AS v FROM xs

);

-> inline

SELECT

CASE 'xs'

WHEN 'xs' THEN v*v

ELSE THEN v

END

FROM (

SELECT 'xs' AS tag, x AS v FROM xs

);

-> constant fold

SELECT v*v

FROM (

SELECT 'xs' AS tag, x AS v FROM xs

);

-> simplify

SELECT x*x FROM xs;

So, inlining is a very important, powerful tool. Lots of optimizations that look "dumb" are actually really important because SQL databases often need to deal with queries with lots of superfluous components if they were generated by an ORM, or multiple layers of query building tool that don't pass sufficient information around to know when things will be empty.

Unfortunately, naive inlining can violate our desire for plan sizes to grow linearly. Consider the sequence of queries defined by:

q0 = SELECT x FROM xs

qn = SELECT x+x AS x FROM (q{n-1}) xs;

The first few queries in this sequence look like:

SELECT x FROM xs;

SELECT x+x AS x FROM (SELECT x FROM xs) xs;

SELECT x+x AS x FROM (SELECT x+x AS x FROM (SELECT x FROM xs) xs) xs;

SELECT x+x AS x FROM (SELECT x+x AS x FROM (SELECT x+x AS x FROM (SELECT x FROM xs) xs) xs) xs;

We can get a vibe of the size of the query plan by using EXPLAIN. In Postgres we can do this:

# explain (format json, verbose) SELECT x+x AS x FROM (SELECT x+x AS x FROM (SELECT x+x AS x FROM (SELECT x FROM xs) xs) xs) xs;

QUERY PLAN

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[

{

"Plan": {

"Node Type": "Seq Scan",

"Parallel Aware": false,

"Async Capable": false,

"Relation Name": "xs",

"Schema": "public",

"Alias": "xs",

"Startup Cost": 0.00,

"Total Cost": 80.12,

"Plan Rows": 2550,

"Plan Width": 4,

"Output": ["(((xs.x + xs.x) + (xs.x + xs.x)) + ((xs.x + xs.x) + (xs.x + xs.x)))"]

}

}

]

(1 row)

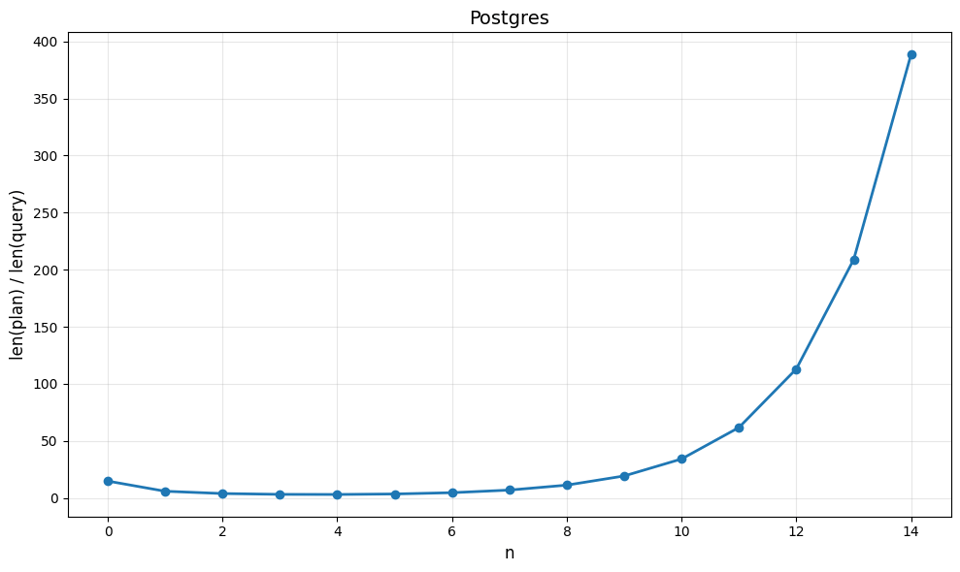

Plotting the ratio of the lengths of the queries to the lengths of the explains in Postgres, we get:

Exponential growth!

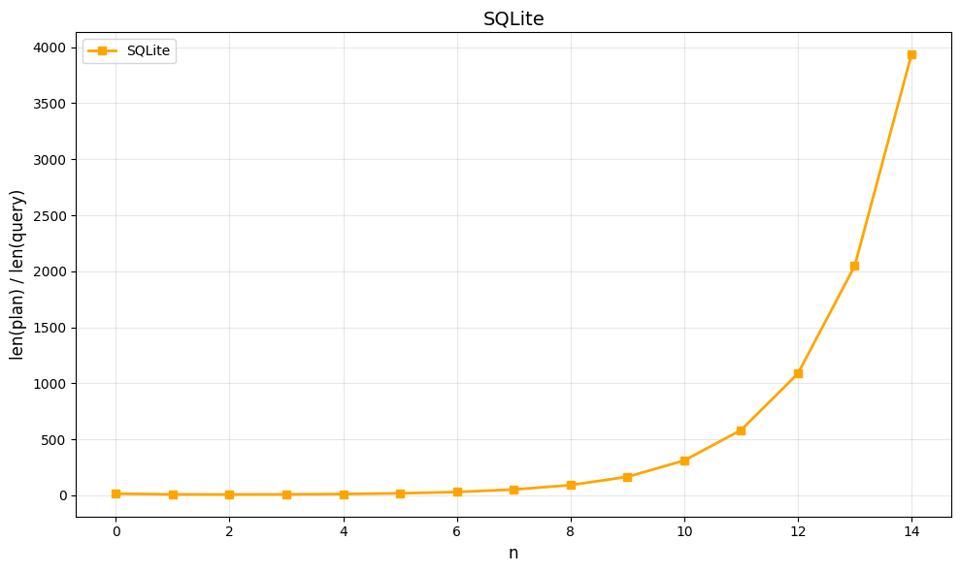

SQLite is no better here:

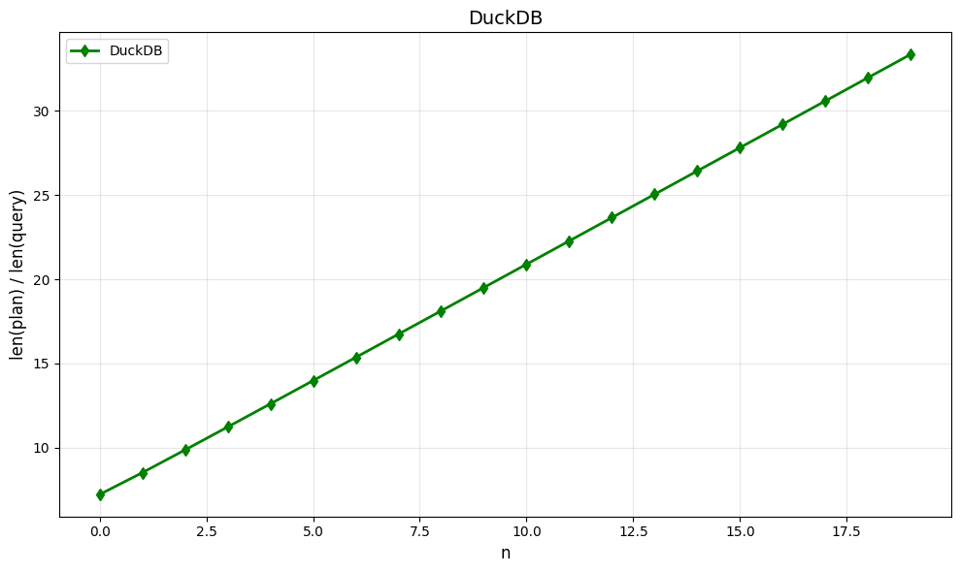

DuckDB gives us the linear shape we crave (note that this actually means that the size of the textual representation of the plan is growing quadratically, mostly due to increased indentation:

At the cost of doing no inlining here at all:

{

"name": "PROJECTION",

"children": [

{

"name": "PROJECTION",

"children": [

{

"name": "PROJECTION",

"children": [

{

"name": "SEQ_SCAN ",

"children": [],

"extra_info": {

"Table": "xs",

"Type": "Sequential Scan",

"Projections": "x",

"Estimated Cardinality": "0"

}

}

],

"extra_info": {

"Projections": "x",

"Estimated Cardinality": "0"

}

}

],

"extra_info": {

"Projections": "x",

"Estimated Cardinality": "0"

}

}

],

"extra_info": {

"Projections": "(x + x)",

"Estimated Cardinality": "0"

}

}

I don't know enough about DuckDB to say whether it does this kind of inlining in other contexts, but it doesn't do it here, which makes it a tad bit safer for this kind of query, I guess.

Anyway, all this is trade-offs; as you can see, Postgres and SQLite, which are two very reliable pieces of software, just freely do the inlining and eat the risk of exponential growth. DuckDB appears to make the opposite trade-off, although I don't know the extent of it.

I'm not sure what the right answer is here, I think you probably should inline up to a (fairly high) "size" limit, so that you don't miss out on any important optimization opportunities, but then cap out somewhere so there isn't unrestricted exponential growth. If you've worked on a system that navigated this trade-off, please let me know!

Add a comment: