Fortran Parsing Algorithm

My friend taught me a really funny parsing algorithm this week and sent me Operator precedence by textual substitution. I love really funny parsing algorithms, so I wanted to try to figure out and explain why this algorithm works:

An ingenious idea used in the first FORTRAN compiler was to surround binary operators with peculiar-looking parentheses:

+and-were replaced by)))+(((and)))-(((

*and/were replaced by))*((and))/((

**was replaced by)**(and then an extra

(((at the left and)))at the right were tacked on. The resulting formula is properly parenthesized, believe it or not. For example, if we consider "(X + Y) + W/Z," we obtain((((X))) + (((Y)))) + (((W))/((Z))).

This is admittedly highly redundant, but extra parentheses need not affect the resulting machine language code. After the above replacements are made, a parenthesis-level method can be applied to the resulting formulas.

It's my belief that this algorithm is a variant of precedence climbing, or can at least be understood as such. So, let's first have a brief discussion of precedence climbing. There are other, more detailed explanations of this algorithm, because mine is going to be a little unhinged.

We want to be able to correctly parse expressions that look like 1+38*12+8*1*2*3+4. Let's ignore parentheses today, and trust we can work it out later.

First, here's an algorithm that works:

import re

plus_re = re.compile(r'\s*[+-]\s*')

times_re = re.compile(r'\s*[*/]\s*')

def parse(s):

return [times_re.split(term) for term in plus_re.split(s)]

print(parse("1+38*12+8*1*2*3+4"))

[['1'], ['38', '12'], ['8', '1', '2', '3'], ['4']]

This illustrates the structure of the kind of thing we're trying to parse, which is:

- An expression is a sequence of terms joined by

+or-, - a term is a sequence of factors joined by

*or/, and - a factor is a number.

This algorithm of course fails in the face of parentheses, which we can fix with actual precedence climbing.

What this illustrates is that to parse at the top level, what we want is some process which replicates splitting on + or -. We want to be able to slurp up everything until we hit a + or -.

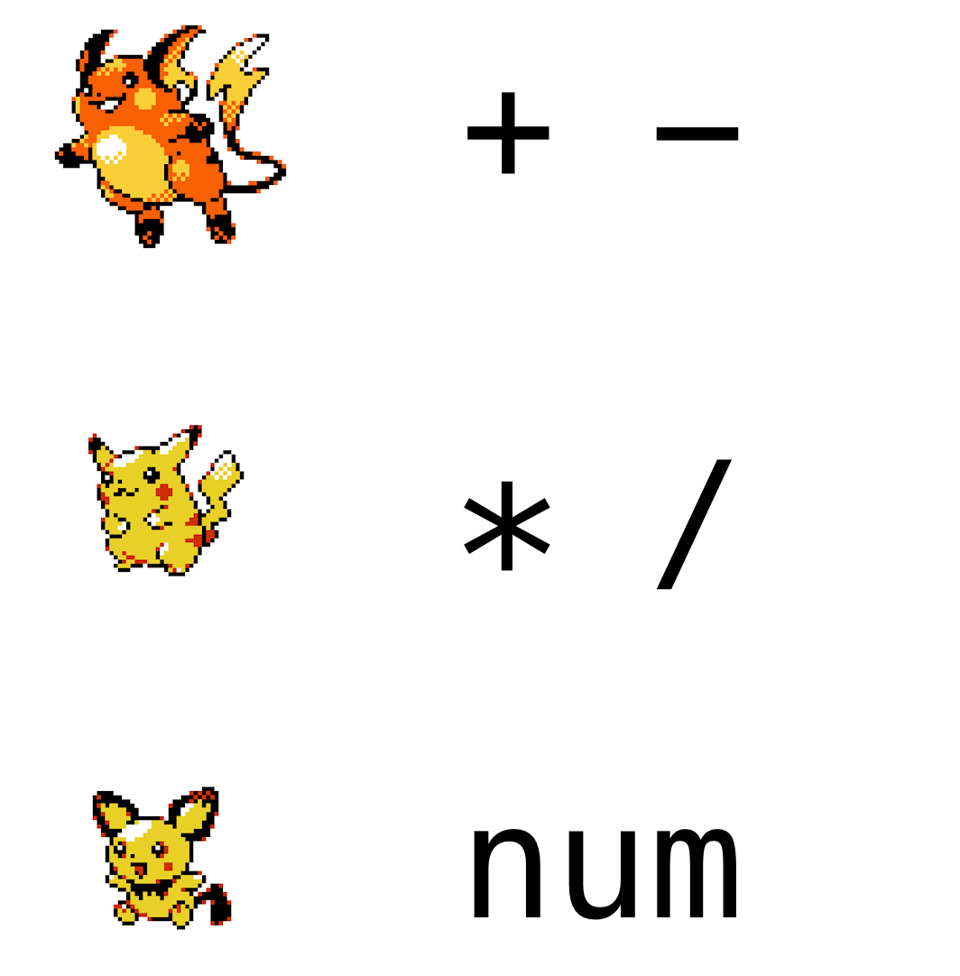

Imagine a stack of Pokemon:

Each Pokemon is only aware of the Pokemon beneath it in the hierarchy: Raichu knows only of Pikachu and Pichu, Pikachu knows only of Pichu, and Pichu is head-empty-no-thoughts.

Furthermore, each Pokemon can only "understand" a certain kind of operation: Pichu can only directly parse numbers, Pikachu is aware of numbers but thinks they're beneath him, and only cares about * and /, and Raichu is aware of everything, but only cares about + and -.

Pichu's job is only to grab numbers:

class Parser:

def __init__(self, s):

self.s = s

self.i = 0

def pichu(self):

result = 0

while self.i < len(self.s) and self.s[self.i].isdigit():

result = result * 10 + int(self.s[self.i])

self.i += 1

return result

p = Parser("100")

print(p.pichu(), p.i)

100 3

^ ^

| Where the pointer into the string is now

The parsed result

Pichu doesn't understand any kind of arithmetic operators, though, so as soon as he sees one, he just stops:

p = Parser("100*200")

print(p.pichu(), p.i)

100 3

Pikachu is different. He doesn't know or care how to parse numbers. he has Pichu for that. And he loves * and /, he just gobbles 'em up.

def pikachu(self):

lhs = self.pichu()

while self.i < len(self.s) and self.s[self.i] in '*/':

op = self.s[self.i]

self.i += 1

rhs = self.pichu()

if op == '*':

lhs = lhs * rhs

elif op == '/':

lhs = lhs / rhs

return lhs

p = Parser("100*200/10")

print(p.pikachu())

2000.0

Like before, Pikachu's little brain can't comprehend things like + and - that exist on a higher plane than him. As soon as he hits one, he throws up his hands and stops parsing:

p = Parser("100*200/10+32*10")

print(p.pikachu(), p.i)

2000.0 10

Now, we can understand Pikachu as doing the same task as plus_re.split: he consumes numbers separated by multiplicative symbols until he hits an additive symbol and stops, so he sort of splits the input string by additive symbols. Luckily, this is exactly what Raichu wants:

def raichu(self):

lhs = self.pikachu()

while self.i < len(self.s) and self.s[self.i] in '+-':

op = self.s[self.i]

self.i += 1

rhs = self.pikachu()

if op == '+':

lhs = lhs + rhs

elif op == '-':

lhs = lhs - rhs

return lhs

Raichu is exactly the same as Pikachu, but instead of asking for the next number, he's asking for the next term. Which he then processes directly.

p = Parser("100*200/10+32*10")

print(p.raichu(), p.i)

So, from Raichu's perspective, every expression looks something like:

stuff + stuff - stuff + stuff

And he delegates to Pikachu to actually produce the stuff.

From Pikachu's perspective, every expression looks something like:

stuff * stuff * stuff / stuff

And he delegates to Pichu to actually produce the stuff.

Now let's return to the problem of handling parentheses in such an expression. Essentially, Pichu wants to defer back up to Raichu whenever he sees a (, and then he expects to see a ). It's an easy change to the code:

def pichu(self):

if self.s[self.i].isdigit():

result = 0

while self.i < len(self.s) and self.s[self.i].isdigit():

result = result * 10 + int(self.s[self.i])

self.i += 1

return result

elif self.s[self.i] == '(':

self.i += 1

v = self.raichu()

assert self.s[self.i] == ')'

self.i += 1

return v

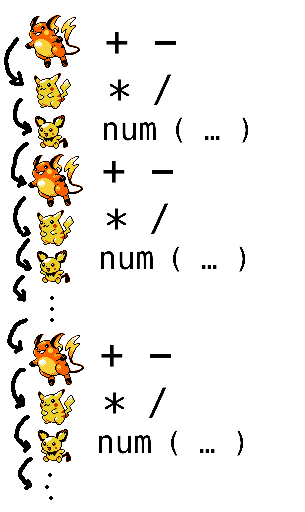

What we're doing here is introducing an infinite stack of Pokemon:

Where Pichu can refer to a lower-level Raichu.

Let's turn our attention back to the Fortran parsing algorithm. The claim is that this function produces a correctly parenthesized expression (we'll ignore exponentiation, and just leave ourselves to two levels). Let's begin without an expression that already has parentheses:

def fortranify(s):

return "((" + s.replace("+", "))+((").replace("-", "))-((").replace("*", ")*(").replace("/", ")/(") + "))"

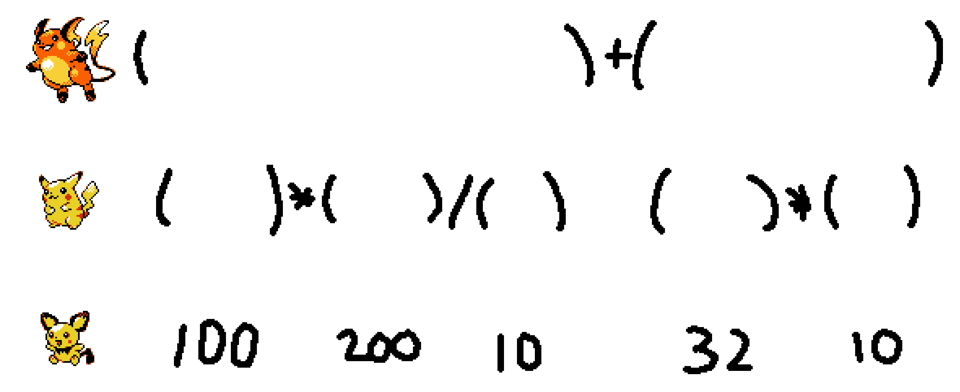

print(fortranify("100*200/10+32*10"))

We can see that on our example, it's correct:

((100)*(200)/(10))+((32)*(10))

The reason we introduced our abstract cast of characters before is that they're a way to understand how this trick is working.

Here's our new setup. When anyone sees an open parenthesis, they begin passing control down to the Pokemon beneath them in the hierarchy. When they see a closing parenthesis, they pass control back up to the Pokemon above them in the hierarchy. In this way, the parentheses can be thought of as instructions: ( says hop down a level, ) says hop up a level:

And we can see that this has split up the example exactly like how each of the Pokemon expect to see an expression: Raichu sees terms separated by additive operations, Pikachu sees factors separated by multiplicative operations, and Pichu just sees numbers. Via this parenthesization, we've recreated the structure that we used precedence climbing to enact. So, let's look at how the rules for the Fortran algorithm bring this about:

- Begin with a

((, this always passes control to Pichu. We're always, by default, at the level of Pichu. - Whenever we see a

+, replace it with))+((. This passes control back to Raichu, lets him process the+, then passes it back down to Pichu. - Whenever we see a

*, replace it with)*(. This passes control back to Pikachu, lets him process the*, then passes it back down to Pichu. We don't have any risk of hopping back up to Raichu here, because remember we are by default in Pichu mode. - End with a

))to pass control back to Raichu to end things.

To cap it off, to handle parentheses in the original expression, we need to triple-escape them:

def fortranify2(s):

return "((" + s.replace("(", "(((").replace(")", ")))").replace("+", "))+((").replace("-", "))-((").replace("*", ")*(").replace("/", ")/(") + "))"

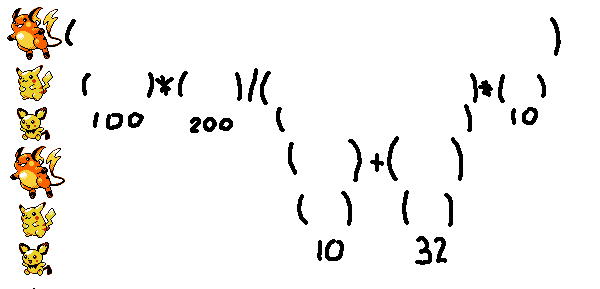

print(fortranify2("100*200/(10+32)*10"))

((100)*(200)/((((10))+((32))))*(10))

This corresponds to hopping down to the Pichu level of an entirely new step in our infinite hierarchy of Pokemon:

And that's it, I personally find that analogy sufficiently convincing that this algorithm works. Precedence climbing is something I have to re-teach myself every time I want to use it because it's a little mind-bending for me, but I think it's a thing I find personally valuable to be able to just write without a reference. It's a fundamental computer technique; you should have it memorized.

I really like this Fortran algorithm, it's a little goofy, a little cute, and very fun.

Add a comment: