Fine! I'll Play With Skiplists

Follow me on Bluesky!

A Log-Structured Merge tree, or LSM, is a popular data structure for storage engines. It’s what is used by RocksDB, which is sort of the poster child LSM. At a high level, the way an LSM works is that new writes get added to a memory-only index called a memtable and a durable file called a write-ahead log, or WAL. The memtable is used to serve queries and the WAL is used to provide durability. When one of those things gets too big, the entire in-memory index gets flushed out to an immutable indexed file called a sorted string table, or sstable, or sst. Since that file is durable, we no longer need it to live in the WAL, and since it is indexed, we no longer need it to live in the memtable, so we can clear both of those out and reclaim their space.

I have a personal, pedagogical interest in trying to express the idea of an LSM in the simplest possible terms. It's generally my view that from a bird's eye view LSMs are simpler than on-disk Btrees, largely because they are more composable and a lot more of their data is immutable (so outside of the one really mutable part, the memtable, concurrency is easy). This also makes them harder to tune for particular workloads since there’s a lot of moving pieces. But generally, you can abstract the various subcomponents of an LSM pretty well.

When getting a little more in the weeds and actually explaining how to implement the individual components, I often stumble at the memtable. Because like I said, it's really mutable. And generally needs to handle concurrent writes well, or at least have reads concurrent with writes. Because the traditional data structure is a lock free concurrent skiplist, which, to explain, requires a trip into some fairly fiddly and subtle concurrent programming (which is not something I have a lot of comfort with). So I'd like to find a substitute for the purposes of explanation. And. Well. Unfortunately I keep coming back to the lock free concurrent skiplist as the best option. So I have been forced to gain comfort with the lock free concurrent skiplist.

Let's explain in more detail the problem we are solving. Assuming you are supporting concurrent access, the memtable must:

- Support fast reads, certainly point reads, and probably forward range scans as well, and probably reverse range scans as well (although for pedagogical purposes I'd happily drop this requirement if it simplified things).

- Since those reads must be merged with SSTs, they might be long-lived, and those long-lived iterators must not block concurrent writes. This rules out coarse-grained locking.

- Even if you don't support a logical range scan, you need to support at least one ordered (nonconcurrent) scan during flushing to build the SST from it. This rules out a hash table (unless you sort it before you flush it).

- Writes should generally be linearizable. This rules out thread-local unsorted buffers that get merged in to a common data structure periodically.

That’s a lot of potential data structures that are no good*!

The use case also offers one nice simplification: it gets to be insert-only. You’re going to be inserting tombstones to represent removed keys anyway (which are interpreted externally), and when it gets full you just discard the whole thing, so you don’t have to dedicate any complexity to deletions. This actually simplifies the skiplist a lot, if you look at a lock free skiplist that supports deletions, it's way more complicated than one that doesn't.

Databases often want to have bounds on their memory usage. One common technique for this in the memtable is to allocate two of them, each backed by an arena. When one memtable gets full and starts having to reject writes, you make it read-only, start flushing it to disk, and swap in the second (which by now is hopefully fully flushed and empty) memtable. Then once you finish flushing one memtable you reset your arena and you have an empty hunk of memory to use for your next memtable. To this end it’s nice if your data structure doesn’t require too much moving around of data that makes an arena annoying to use.

Anyway, a lock free skiplist is a very obvious response to all these constraints. It’s highly concurrent, ordered, and linearizable (as long as you’re careful to ignore new data). But it's not the simplest data structure: it requires atomics and some optimistic concurrency control and a couple nontrivial observations. Not having to support deletions is a pretty substantial simplification, but there’s still a lot of meat if your goal is to write “the simplest possible LSM.”

As a quick overview, a skiplist is basically just a linked list with a bunch of extra linked lists used as shortcuts, each of which has fewer elements than the last. You decide what to include at a given level by filtering out elements from the previous list uniformly at random with probability p. It's traditional to think of this as each node having a "height" which is chosen from a random variable that's geometrically distributed with parameter p, and for each possible height, there are links between successive nodes that are at least that tall.

A big reason to do this with randomness is to avoid coordination between multiple writers: in expectation, you wind up with a nicely shaped search structure.

When you do a get operation, you start from the highest level and find the first level where the sought key is between two nodes, then you descend to a more granular level and continue until you hit the bottom level (which is the source of truth: values are "in the skiplist" if and only if they are in the bottom level).

Anyway. That's just to say, I've just been messing around with skiplists this week. I don't really know what I'm doing yet. Here's a couple things I learned.

Writer Concurrency

First, the LevelDB skiplist appears to be single-writer-multi-reader, this was surprising to me, since it's a nice feature of skiplists that they can support multiple concurrent writers. By contrast, the RocksDB and Pebble skiplists are multi-writer-multi-reader.

At a high level, the distinction is basically in how you insert a node.

In a single-writer case, insertion looks like this:

...

// find the location to insert the new value.

prev, curr = Find(key)

// `prev` is < node, `curr` is > node.

node := NewNode(key)

// no synchronization needed here, because `node` is

// not yet visible to other threads (because no pointers

// yet point to it):

node.next = curr

// this part must be done atomically since a reader might be

// traversing the list right now:

atomic.StorePointer(&prev.next, node)

And then you repeat the process for the upper levels.

To support multiple writers, what can go wrong is that in between finding prev and curr, another thread can come in and insert a different element in between them, which means you're no longer looking at two adjacent nodes in the list. This means that inserting the new node by making node point to curr and prev point to node might lose that other write.

The solution is to use a compare-and-swap (CAS), which is an operation that atomically checks that a value is what you expect it to be, and replaces it only if the check succeeded. If someone else came in and inserted something else between prev and curr, our CAS will fail because the value of prev.next will have changed, and we need to start over:

for {

// find the location to insert the new value.

prev, curr = Find(key)

// `prev` is < node, `curr` is > node.

node := NewNode(key)

// no synchronization needed here, because `node` is

// not yet visible to other threads (because no pointers

// yet point to it).

node.next = curr

if atomic.CompareAndSwapPointer(&prev.next, curr, node) {

// success!

break

}

// we failed, so try again.

}

This is a form of optimistic concurrency control.

The one I implemented was multi-writer-multi-reader but I haven't benchmarked it against anything yet. It doesn't add that much additional complexity, at least in the no-deletes case. Maybe I have subtle lurking bugs, though!

Height

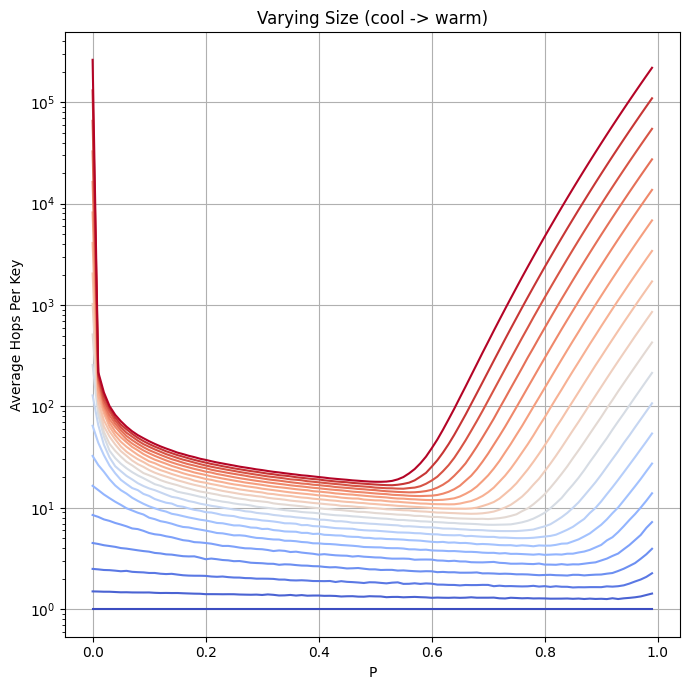

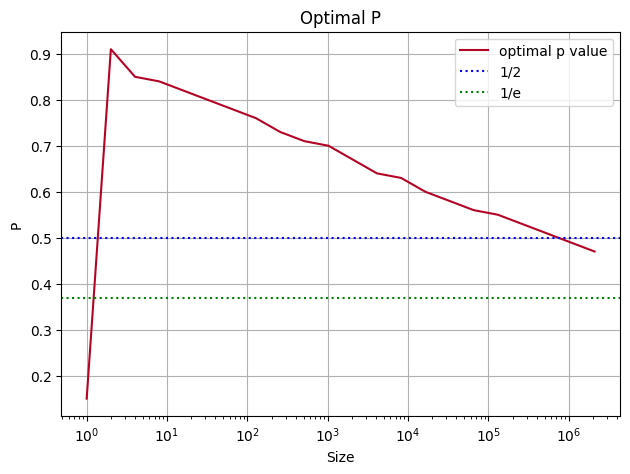

One thing I noted was that the Pebble code asserts that the optimal value of p is 1/e. I haven't been able to find reference to this fact anywhere else but it sounds plausible to me. After giving up on trying to figure out why this might be true analytically (a friend found a closed form for me but the result was numerically unstable and hard to evaluate and analyze which is beyond my expertise) I turned to the succor of modern computing machines and ran some simulations:

This plots the average number of pointer traversals required to find a node in a skiplist with the given value of p with a max height of 16. Different colour curves are over different quantities of values (each curve contains twice as many values as the one beneath it). The values start from a single element skiplist (the coolest value) and warm up to 2^21. You can see the optimal value creep backwards as the number of values in a skiplist climbs, I think it's believable? That the optimal value here approaches 1/e as the number of values goes to infinity (though it looks like there might be a better value depending on how many values you expect your skiplist to contain). Here's a plot of the optimal value of p for different numbers of values:

I will go further when I have more time to run the simulations! I wanted to try to speed up this process by using gradient descent on the simulations but I didn't really know what I was doing and I had to go make soup.

Personally I like p=1/2 just because it lets you compute it in the slick way:

height := 1 + bits.LeadingZeros64(rand.Uint64())

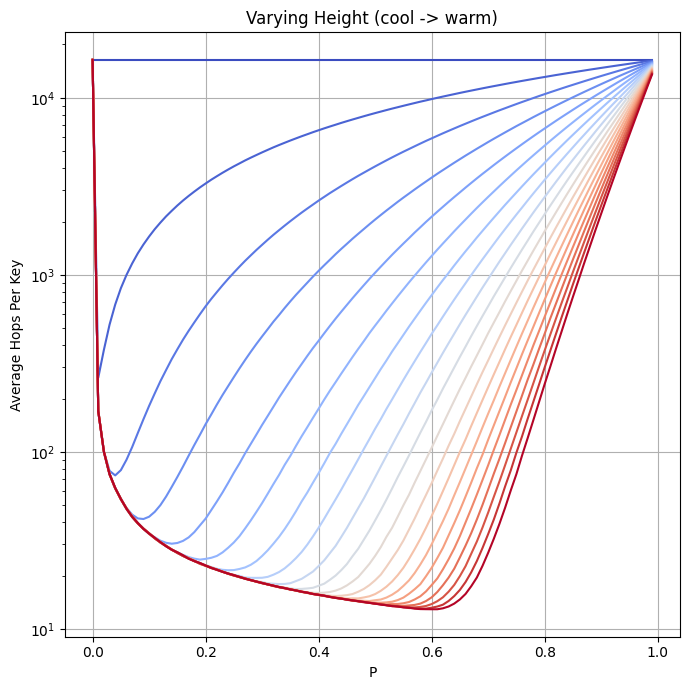

My initial reaction was that the max height of the skiplist doesn't matter that much, since it's with fairly low probability that you ever get that high. But of course, as the number of elements and in particular, the value of p increase, it starts to matter more, since you'll reach that high value more frequently. I plotted the curves for a bunch of different values of the max height:

I will keep messing around with these until I am comfortable with them, or I get bored, I guess. But I am eager for insights! If you have any, please reach out here (you can reply or leave a comment) or on Bluesky.

Links

- I realized too late I have this paper bookmarked and I didn't get a chance to read it for this post. I will read it though.

* One idea I'm interested in messing more with is some kind of copy-on-write Btree, but that's for another time.

Add a comment: