Expectation and Copysets

That expectation is linear is one of my favourite facts. I got a first taste of this when I was doing an internship at an unnamed trading firm. Some guy was teaching me the basics of trading and showing me how traders (of which I was not one) were expected to have heuristics that would allow them to make snap judgments about things like expectation.

As an example, he asked me, in more words, what the expected rank when flipping over the top card of a deck of cards was (A=1, J=11, Q=12, K=13). This is easy to compute directly as 7. Then he asked me the expectation of the sum of the top two cards. Off the top of your head, this might seem a lot harder, because the rank of the second card is not independent of the rank of the first card: if the first card has a low rank, then the value of the second card is likely to be higher, because there are fewer low ranks it could be. So you might think, "ah, shit, well, I guess I need to condition on the rank of the first card, or something." But this is actually not true: the answer is that the expected rank is simply 7 + 7 = 14, and the reason is that expectation is linear.

Without getting too precise, the expectation of some outcome is the average value over all possible outcomes. If, after we do some process (say, shuffling cards), we look at a result (say, the rank of the top card), and call it X, then E[X] is the average value of X across all possible ways we could do the process (weighted by how probably each is).

If X is the rank of the top card, and Y is the rank of the second highest card (which remember, are not independent), then we write the expected value of their sum as E[X + Y]

When we say "expectation is linear," we mean that E[X + Y] = E[X] + E[Y] and E[aX] = aE[X]. The fact that expectation is linear is easy to show if you just look at the definition, which we will not do here, but I trust you are capable of if you are interested and have not already seen it.

Since expectation of linear, we know that in our card-flipping example, E[X + Y] = E[X] + E[Y] = 7 + 7 = 14.

This, like a lot of mathematical facts, can be interpreted in two ways: one, "I'm so powerful in this situation, no matter how the terms are shuffled around, I can always find the same expected value," or two, "I'm so weak in this situation, no matter how I shuffle the terms around, I can't change the expected value."

There are many classic applications but I want to talk about one that is relevant to the study of distributed systems.

Copysets

Copysets: Reducing the Frequency of Data Loss in Cloud Storage is a cool paper, and a fellow linearity of expectation enthusiast pointed out to me that the core idea is a consequence of linearity (the paper itself also calls this out).

The setup is that we have a set of n servers, and we have a set of m pieces of data that we need to distribute across all of them. We want each piece of data replicated, say, three times. So each piece of data should live on three servers.

Let's say at a particular window, each server has probability p of failing. A given piece of data is lost if all three of the servers it lives on fail at the same time. So, in a given window, a given piece of data is lost with probability p^3, and by linearity we can consider each piece of data in isolation, so the expected amount of data lost is simply mE[p^3]. That's right: the distribution of the data, how we spread it out among the servers, impacts not at all the expected amount of data loss.

Does this mean that where we put the data doesn't matter? No, of course not, there's a whole universe of possible distributions of data loss outcomes that depend on how we allocate the data, it's just that linearity tells us that all of those distributions have the same expected value.

Understanding this lets us intuit some of the design space that's available to us. Say we "scatter" the data, so every piece of data picks three random servers to be stored on. Then, with high probability, any three servers dying will result in data loss. On the other hand, if we put all the data on the same set of three servers, and ignore all the others, exactly those three servers must fail in order for us to lose data. So what's the catch? How can both of these have the same expected amount of data loss? Note that in the first case, when we lose data, we only lose a bit; the data that happened to choose exactly those three servers. In the second case, we lose a lot: all of it! It's just that the second case is much rarer than the first case.

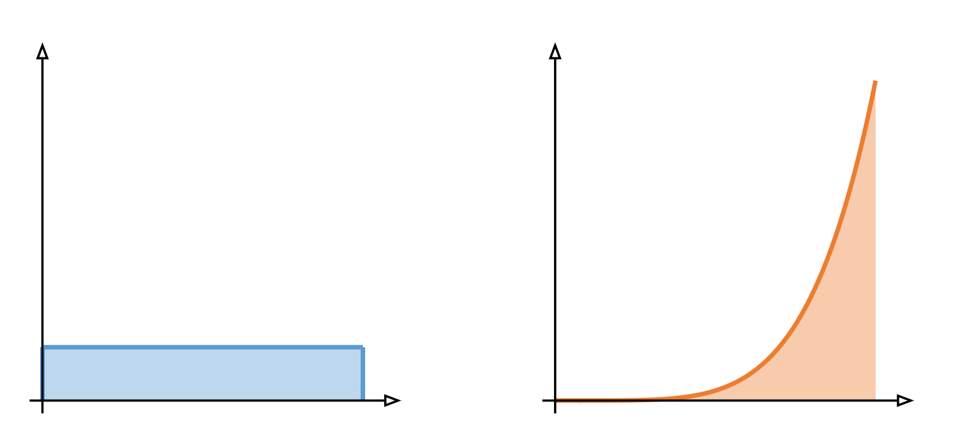

How to think about this is: you have a curve, and you're not allowed to change the area of it, but you can change the shape of it, as long as the area stays the same:

Both distributions have the same area, and thus expected value, but one pushes most of that area to the tail, so when the bad thing happens, it's really bad, but it happens less frequently.

This is the idea behind copysets: instead of having every piece of data randomly assigned to a set of servers, we group pieces of data together and have them all share a set of servers. It's not quite as extreme as putting all the data on the same three servers, which wouldn't actually make any sense to do, but it has the same effect of pushing all the failures to the tails.

Add a comment: