#6: a long-term relationship with a country that's not your own

an interview with author rafe bartholomew

Hi and welcome to Other Kinds of Intimacy.

Before we get into it, and speaking of one’s relationship to a country, if you’re looking for ways to fight fascism in the U.S., my friend Yowei put this list together. I’m watching what’s going on in Philly, where the resistance looks like federal judges speaking out about ICE’s tactics and legislation to limit ICE’s powers in the city, but also grassroots efforts like queers organizing “ICE Out” trainings and Filipinos hosting an adobo cookoff to raise money for immigrant rights orgs.

Now to this week’s letter.

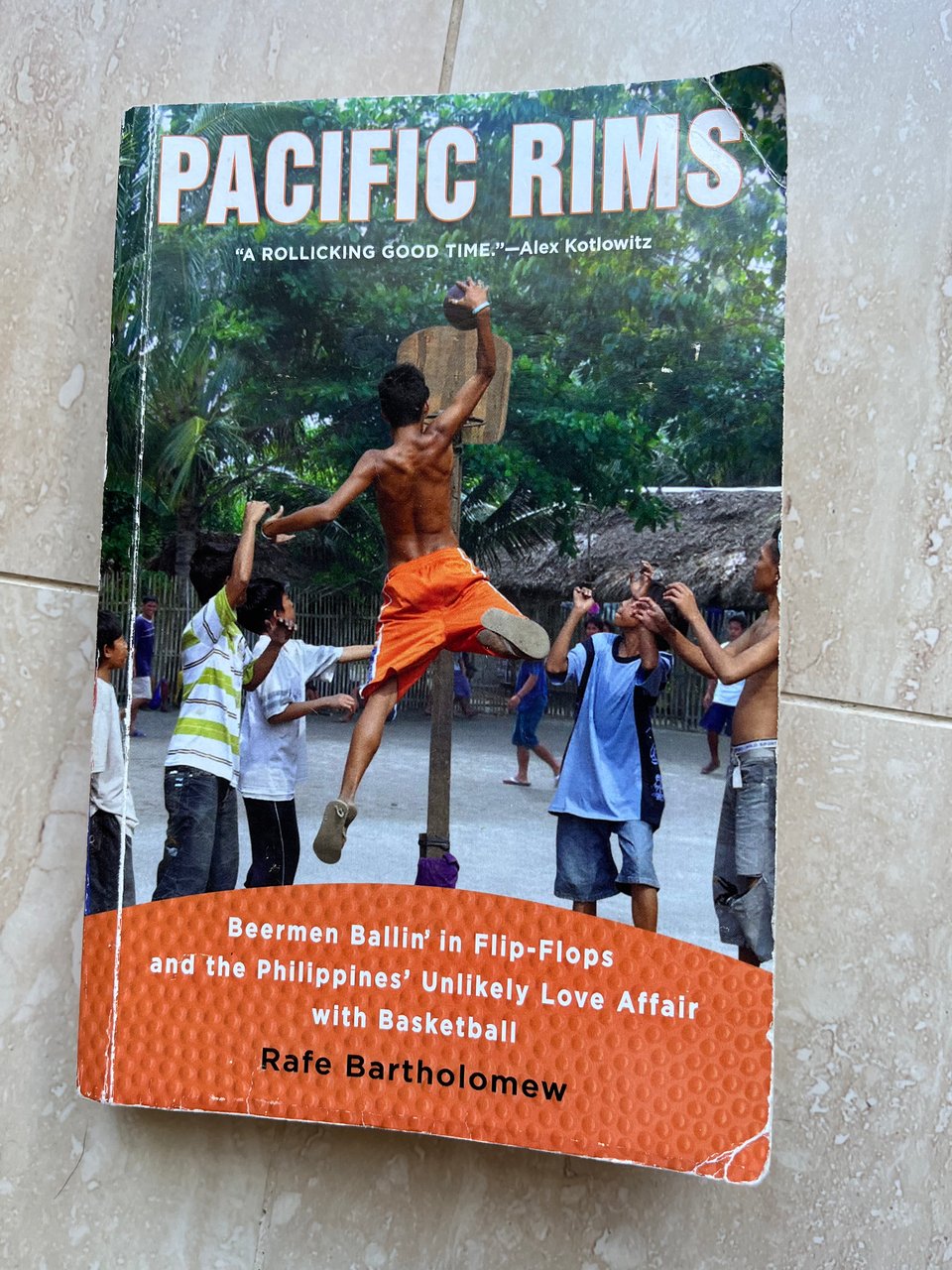

Ever feel like a book is fated for you? That somehow, however improbably, it was always going to find its way to you, and at exactly the right time? That’s how I felt about Rafe Bartholomew’s Pacific Rims, a gem of a narrative nonfiction book about basketball in the Philippines. When it came out in 2010, my first editor (hi Doron!) told me about it, thinking I might be interested because of the Filipino tie but I was like, uh, basketball? And returned to my Jonathan Franzen.

Nearly fifteen years later, I had a strange urge to get the book, seeing it as inspiration for a dream of mine, to report on the Philippines. When I moved to Manila the following year, it was one of the dozen or so books I packed.

I soon after (however improbably) fell in love with Filipino college basketball and finally read Pacific Rims, staying up late in bed with it, marveling at not only the reporting and the easy, extremely funny voice but the way the writer had immersed himself in the country.

The book follows Rafe, a white guy from New York City who, at 23, goes to the Philippines on a Fulbright to study the uniquely Filipino love of basketball. He embeds with a Philippine Basketball Association team and pores over old newspaper clippings in the library. But he also learns Tagalog, gets a Filipino nickname, drinks with the tricycle drivers in his neighborhood, and navigates the city by jeepney and light rail and on foot (to many people’s horror, because if you can afford to avoid doing so, you do). One year in Manila becomes three.

When I looked him up after reading the book, I was surprised to see that after all these years, and despite living in the States, he still seemed immersed in the culture. On his Twitter/X account alone, I spotted an OPM playlist, deep-cut Filipino basketball memes, lots of Tagalog. His location: “New York Cubao (I wish!)” (Which I actually only realized was a real place when I saw it referenced in the Pinoy movie Four Sisters and a Wedding.)

This is not standard behavior for journalists, or people who live abroad, at least it’s not the story you hear—someone building, and sustaining, a long-term relationship with a country and culture that isn’t their own. It’s something I’m deeply interested in, as someone who’s trying to build, or rebuild, a relationship with a place that I can only tenuously lay claim to.

Last month, I got to talk to Rafe over Zoom—me in Manila, him in the Detroit area, where he lives because his wife went to med school there. He told me that even though he sees the Philippines as a second home, he still experiences the country through the eyes of an outsider. It’s one of the privileges of being a foreigner, he said, this way of seeing that makes you feel more alive to your surroundings.

“I still walk around wide-eyed all the time,” he said, even though it’s been more than twenty years since he first set foot in Manila. “I wish I could make myself look at life in the States the way that I look at life in the Philippines.”

His enduring relationship with the country tracks with what I found on Twitter: It’s easier for him to name the years he didn’t make it to Manila for a visit. He has a subscription to The Filipino Channel, watches Pinoy news shows like 24 Oras, easily switches into speaking English in a Filipino accent (which, as my cousin put it the other day, sometimes feels harder than speaking Tagalog). And he set me straight when I called Jacob Cortez the second coming of Mike Cortez.1

My favorite moment of the interview was when we shared our OPM karaoke songs—Parokya ni Edgar’s “Buloy” is one of his—and when I told him mine, “Nosi Balasi” by Sampaguita, he was like, hold on, opened the drawer behind him, and pulled out a shirt bearing the words NOSI BALASI.

You can read edited excerpts from our conversation below.

Some of what we talked about:

the food craving that signaled he had started to assimilate into life in the Philippines

why his time in the country felt like a coming of age, and

why he’ll never say he’s “basically Filipino.”

‘I've crossed the Rubicon here’

When did you start feeling like you understood Manila?

One of the moments that sticks out for me, I can't put a date to it, but after a year and a half, two years, I would be on my way to one of the basketball games with that group, that open run group, and I found myself just wanting either Jollibee or McDonald's spaghetti.

I was like, oh, I've crossed the Rubicon here, because, you know, when I first tried it, I was like, this is OK, but it's weird. This is not spaghetti I'm used to2. And then all of a sudden, I was like, I need this. This is my pre-game meal. It’s the perfect size. It's not gonna weigh me down.

‘I didn’t want to let that go’

What made you want to keep returning to the Philippines?

For whatever reason, it seemed like, I don't want to just use this as a resume building opportunity where I was here for a year, I had this cool grant, and now I go back and embark on my career doing whatever it is I'm actually supposed to do. Honestly, I think that's because living in the country, I felt like, this actually is what I am supposed to do.

You mean journalism? Or…?

Writing about the Philippines. Which, you know, I haven’t always done over the years. It’s not that easy from here. So I think over the years, it’s developed into just being a big part of my life is there and I don't want to let that go.

I remember a few times when I would come home to New York, I'd go home to the apartment where I was born and raised, same block I walked up and down for as long as I could remember, where I commuted every day for high school.

And other than the people in my building, I didn't know anybody up and down that block as well as when I would come and walk around Loyola Heights, Katipunan area in Quezon City and know everybody, have people calling out to me, like, Paeng! Wowowee!3 And all this stuff to me, and it’s just like, that got through to me in a way that I didn't want to let go.

‘I feel like I grew up again’

When I moved to the Philippines, I was 23 years old, and within a few months of me moving, my mother died. She'd been sick for years, she had cancer. And, I mean, you asked about turning points earlier. That was not a turning point in terms of my knowledge or familiarity or being able to get around the country, but I think it was in terms of, it was one of my parents, one of the things that tethered me to my life before.

So in some ways, probably sounds naive, but I feel like I grew up again, or had a coming of age over the next few years living in Manila because it just felt like I was cut off from everything that came before, and it gave me this new start. Not even one that I was seeking. I was just like, all right, this is, to some degree—it wasn't true, but I felt like, what happened in the States doesn't matter. Like, let's be here now

On the privilege of being ‘a big white American guy’ who speaks Tagalog

Do you have any complicated feelings about being a white man who’s immersed in Filipino culture, given the history and cultural context of white men in the Philippines?

While I'm proud of the fact that I feel very comfortable in the country, know my way around, can speak Tagalog well enough to get around most of the country, and in some cases, well enough to be on TV, although these days I probably sound a little bit baluktot, I'm pretty firm, both in my head and with other people about never doing the kind of stuff where it's like, Oh, I'm basically Filipino. I don't believe that.

I mean, people who are Filipino are Filipino. I am not. That's fine. I am a white person from New York who has lived in the Philippines and speaks Tagalog. I can tell you about the experiences that led me to this point in my life where the Philippines is a major part of who I am, but it still does not make me Filipino.

I encounter a lot of people who will say in a really complimentary way, parang kang Pilipino (you’re like a Filipino) or mas Pilipino ka kesa sa mga ibang whatever (you’re more Filipino than others). I'm not going to go out of my way to correct people because to me, that's rude, but I don't encourage it, and I just sort of nod and smile and let it pass, or even people saying like, you know, pusong Pinoy ka (you have the heart of a Filipino), you know, stuff like that.

Again, I'm proud of the experiences I've had, the fact that I've been able to assimilate. But also, it’s a shame that it's so remarkable that at the level that I've achieved, people are that impressed.

I'm aware that I get a level of encouragement and just, I don't know, affection, that I wouldn't get if I wasn't a big white American guy. I can't change that.

But I guess the way that I make my peace with that is, you know, by being humble about it, trying never to take advantage of it in any way, and also trying to make sure that things that have benefited me about the expertise and the work I've done in the country also benefit people actually living there.

I am proud that on both Pinoy Hoops and Hoop Nation for CNN, I was the only foreign part of those productions. Everyone else, the directors, the producers, the cinematographers, everyone else, it was a completely local crew.

‘Meet people in their own words’

Do you have any advice for people looking to build a connection with a new place?

My advice would just be to follow something that you are into, whether it's something you already care about—for me, that was basketball—whether it's something that you discover when you're in another country, like some sort of passion to do frequently that's going to introduce you to a community, and then the rest can kind of fall into place.

For me, it was very important to ride public transportation and see different sides of of Manila, both from the more upper class sides to life on the corners, like making tagay with tricycle drivers in Loyola Heights and Pansol, but that's not necessarily the answer for everyone.

And this is the other great luxury: having the time to do it, like, if you're only going to be somewhere for three weeks, you’re shit out of luck in turning those terms right? If you do get the opportunity to live there for a long time, be open to as much as possible.

The other important thing is if you have the time, study the language. Even in a place like the Philippines, where a lot of people will say you don't need to learn it because almost everyone will understand you speaking English.

And hire a tutor. We're all cheap. Everybody wants to go, oh man, I can just get Rosetta Stone—nobody uses that anymore, but whatever AI bullshit people use to learn language. Yeah, it's easier that way, but it doesn't work. Get a real teacher. You gotta study.

It's worth going, putting in that extra effort and investment and time and money to be able to meet people in their own words, on their own terms. Certainly it changes the way that people respond to me and are excited to talk to me. That's been more important than anything else for me.

That’s it from me. Big thanks to Rafe Bartholomew aka Paeng.

Till Sunday again,

Juliana

“As good as [Jacob and Mikey] are, Mike was a whole different thing in college. Like a transformational player for the entire sport in Manila, not just LaSalle.” ↩

Filipino spaghetti is sweet and hot dog-laden and delicious. ↩

A popular Filipino variety show Rafe ended up on. Some years later, he appeared on another variety show called Eat Bulaga! and I feel the need to insert this gif of the appearance. ↩

“These little rituals of mass humiliation mean something in the Philippines,” Rafe wrote about his televised dance moves, and he was right.

Add a comment: