Ridiculous Opinions #273

This week David Lynch died. I would assume that a lot of people who read this newsletter might not know who David Lynch is. He hasn’t made a movie since, I believe, 2006, and his last creative work that got any attention was the 2017 Twin Peaks revival. It’s been a while. Lynch was 78 years old and had emphysema; smoked like a freight train all of his life. It’s a very sad end for an interesting figure, but most people would pay no mind after perhaps acknowledging that yet another artist had passed.

But hey, folks, I’m Gen X and David Lynch, for me, was a seminal figure during some very formative years in the late-80s, early 90s. Let us travel back to visit a seventeen-year old Randall P. Girdner in Oklahoma, long ago. Randall was an unhappy teen, desperately searching for a tribe that shared common interests with him and failing miserably. When I was young, I used to take refuge in magazines and I spent a great deal of money on Rolling Stone and Premiere (which was THE movie magazine at the time). We were also lucky enough to have a very progressive video store in my hometown that carried absolutely everything. (It was a place called Computamax and where I got my first job at 14 years old…I should write about it sometime).

Because I worked at Computamax, I was exposed to films other than hits like Beverly Hills Cop and Ghostbusters throughout the 80s. They had a more diverse selection. The store would get really weird things like Stop Making Sense and Au Revoir Les Enfants, the boxes of which I would stare at and wonder, What are these strange films with glowing reviews pasted all over the outside of the box? I was intrigued and because this was before the internet, I would have to do my own research to find out what the hell these movies actually were. It was a wonderful way to live. Each movie, director, actor was a tiny mystery that those with a keen eye and resources would be intrigued to investigate.

So once I started working at the video store, I became what can only be described as a proto-version of a “film bro”. I learned things about film-making and filmmakers. If there was something obscure that I needed to watch, I would read about it, then seek it out at Computamax. Sure enough, the movie would be right there, having not been checked out for years (if ever). At fifteen, I was watching obscure things like Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (this was before the Scorsese renaissance) or Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train. If it was weird and it would have given me some sort of cache, then I was watching it, proud of my ability to sit through long, turgid movies and appreciate someone like Spike Lee for She’s Gotta Have It rather than Do the Right Thing.

But I had no one to share any of this awesome knowledge with. No one cared that I was watching these movies and it was a given that no one was going to watch these movies with me. I accepted my fate.

And in this haze of adolescence and anger, along came a filmmaker named David Lynch into my life. David Lynch was a filmmaker’s filmmaker. There are a ton of tribute pieces up right now, so I’m not going to rehash his career for you, but what you should know is that I started reading about him in Premiere. He had a film called Blue Velvet that many considered to be one of the best films ever made (and still do). Being the avant garde teenager that I considered myself to be, I thought, I’m going to watch this movie and love it.

Well, I didn’t love it. In fact, I didn’t understand it. I was young and Lynch was working on a psychological level that was well-beyond my teenage brain. I had no clue what was happening. I had no clue what the symbolism was in the film. I had no clue what kind of drugs this filmmaker was on (turns out, none).

But in my own warped little mind, I appreciated myself for having watched Blue Velvet. At least in my world, I was cool for having done so, even though I didn’t get it (and even though, to this day, I’m still not sure I do). That self-created hipsterness was what I carried around with me.

But around 1990, I read about David Lynch getting involved in television. He was creating a show called Twin Peaks and the critics were going nutty for it. I had to be a part of this glorious television series. And it was glorious. It was 45 minutes a week of a weird, indecipherable murder mystery with characters that were intentionally odd and storylines that made you feel as if someone was playing a joke on you. They might have been. It might have been David Lynch’s joke, as if he was saying, Can you believe they give me money to make this?

And I stuck through with Twin Peaks all through that first season, right up until the chilling conclusion that revealed the murderer of Laura Palmer. I was jazzed by the film-making, which touched on a primal nerve in one’s psyche that no other filmmaker could achieve. It wasn’t all great, but when it was on its game, it was spectacular.

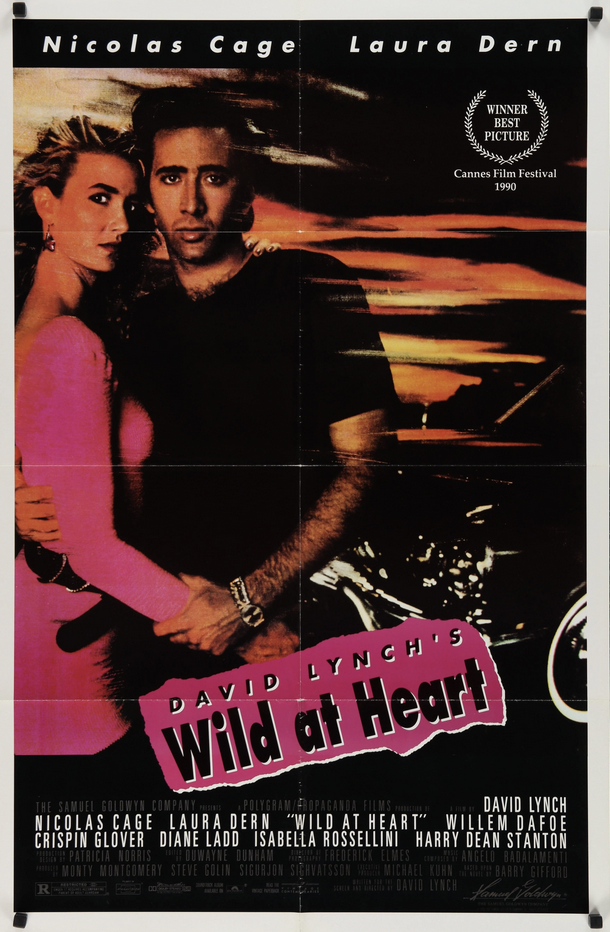

After that, I was all on board with David Lynch. He didn’t produce much afterward, but when he did, I was there, and his next project was a film called Wild at Heart, with a pre-blockbuster Nicholas Cage and Laura Dern playing lovers on the run. When I heard that it won the Palm D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, I knew that it was something that I had to see.

I drove to Tulsa on a Friday night after I got off work as a projectionist at our hometown theater and plopped in at the only place in the city that played art house films (Eton Square, I believe). I sat in my seat for the late showing in a sparsely populated theater, ready to appreciate the genius that is the film-making of my beloved David Lynch. Here’s a wonderful clip from the movie, starring long, lost Crispin Glover:

The whole movie was like that. If you don’t find that absolutely hilarious, then don’t bother watching the film.

I walked out of the theater that night shell-shocked at what I had seen. It was (and remains to this day) one of the weirdest films that one could ever see. It was at once glorious and utterly disturbing, strange and sweet, campy and deadly serious. It was a film that burned its visuals into my brain, like a celluloid depiction of those little nightmares that you experience when you’re just falling asleep and suddenly wake up. I’m not sure that there’s anything like it out there.

As a tribute to Lynch, I sat down last night and watched it again. I’m not sure that I have seen it in the last twenty years, and at first, I thought to myself, Geez, teenage Randy had no taste! The acting was stilted. The story rough. The images disturbing. But what I had to do was get back into that seventeen-year old, open-to-anything mindset to really enjoy it. I have been conditioned over the last thirty-four years to the three-act structure, straightforward storytelling, and traditional acting. I had become numb to film-making and art.

And what ended up happening as I watched the film was that I started to appreciate it for the genius that it was. Nicholas Cage doing an Elvis impression for an entire movie? Check! Dianne Ladd painting her entire face red with lipstick and having a conversation on the phone with a martini in hand? Check! Musical numbers? Check! A man getting his head smashed in on the floor in the first ten minutes? Check! Voodoo? Check! Bobby Peru? Check! Disturbing? Check! Glorious? Check!

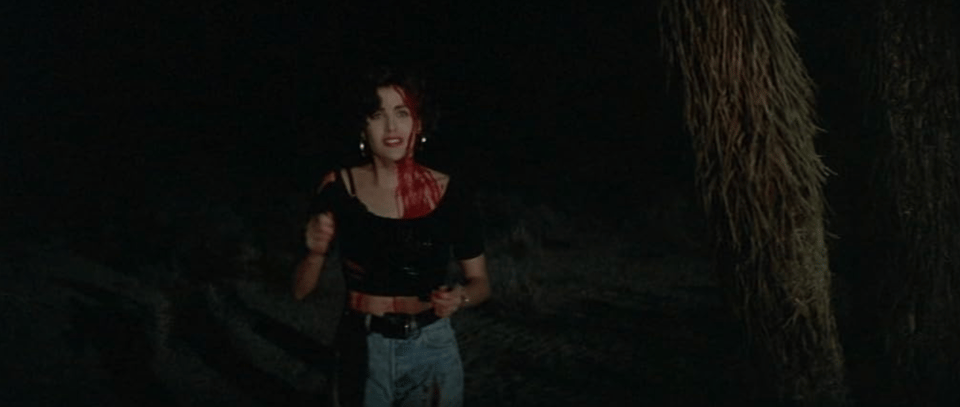

Even as an adult, there are images so striking in this film that they will stay with you for days. Look at this shot of Grace Zabrieski from the movie:

That scene of a ritualistic voodoo killing is so, incredibly disturbing that it’s shocking even today. It’s so out of the blue. So odd. Like a dream come to life. Willem Dafoe as the demented killer, Bobby Peru, is nightmare fuel (be warned…language!):

Dianne Ladd and her lipstick, all in glorious wide screen…

But it’s not just the disturbing stuff. There’s also long, lingering shots like this, with just two people in a car, driving at night:

The scene that affected me most was a scene with Sherilyn Fenn (a Twin Peaks alumnus). The scene has very little to do with the rest of the movie, where Cage and Dern stumble upon a car accident on the side of the road.

I can’t even describe it. It comes out of nowhere and just hits you like a hammer. I vividly remember watching this scene that night in 1990 and driving home in the darkness, wondering what it was all about or whether I would encounter the same thing on the way home. It felt familiar.

The performances in this film are incredible. Dafoe is exceptional as Bobby Peru. Nicholas Cage does the Nicholas Cage thing, but you completely buy into it because he does. Harry Dean Stanton crying because he’s so in love with Diane Ladd is just absolutely hilarious.

But it is Diane Ladd and Laura Dern (mother and daughter) that steal the show. Ladd is absolutely fearless as an actress in this film, an old-school performer devoting every fiber of her being to doing things that very few actors in this day and age would have the guts to do.

And Laura Dern is a revelation. If we’re talking about charisma, she’s got it. Just an absolutely astounding performance where there is not one millisecond where you don’t believe that she is Lula.

By now, I’ve probably lost most of you, and that’s okay. Sometimes, I write these things for myself. I am not recommending that you go out and watch Wild at Heart. You won’t like it. You will be disturbed. You will be annoyed. You’ll think it’s the stupidest thing that you’ve ever seen, and you may very well be right.

But this newsletter today is an appreciation of a man whose vision will never be on the screen again, and that’s unfortunate, even though that’s how life goes. David Lynch taught me to see the world in a new way. His art helped me become an artist. His work, disturbing and glorious as it was, is part of my DNA. I am a better human being for having watched his movies.

I’ll leave you with one last clip. When you watch it, think of the absurdity of the whole thing. But then watch how something so completely stupid turns into something that is stunning in its beauty; the close up of Cage and Dern speaking to each other; the perfect shot of the sunset. This scene, for me, sums up everything that we lost with David Lynch.

Thank goodness I got to enjoy it…

Add a comment: