Love, Ghosts, Power: Who gets to translate what

In which I struggle to know the right thing to do

Hello friends,

I have said before, and will say again, in my endless rehearsal and repetition of the truth of my life, that I came to Yiddish for the ghosts. No one in my living family spoke it with any great confidence, and certainly never to me. It was the family history of Yiddish, the fact that the relatives who spoke and lived in it were just out of reach, one generation back in every case. Even Bubbe Rose, the only great-grandparent who survived into my lifetime was American-born, raised in English, had spoken no Yiddish, merely heard it growing up. That common thread, the sense that Yiddish was a language spoken by long dead grown ups over the heads of now impossibly elderly children, made it spectral and irresistible to me.

This ghostliness — ghastliness? What a slim difference a vowel makes! — serves not just as my motivation for learning Hebrew and Yiddish, but the justification I wield in translating them. My ancestors want me here, pouring over dictionaries, trying to reach out to them through the stories and poems and prayers that catch my eye. Who guides our taste, our eyes, the whims of fortune, if not our loving ancestors? Who could be behind the sublime pleasure I get out of these literary puzzles, if not the people who loved me without ever knowing me?

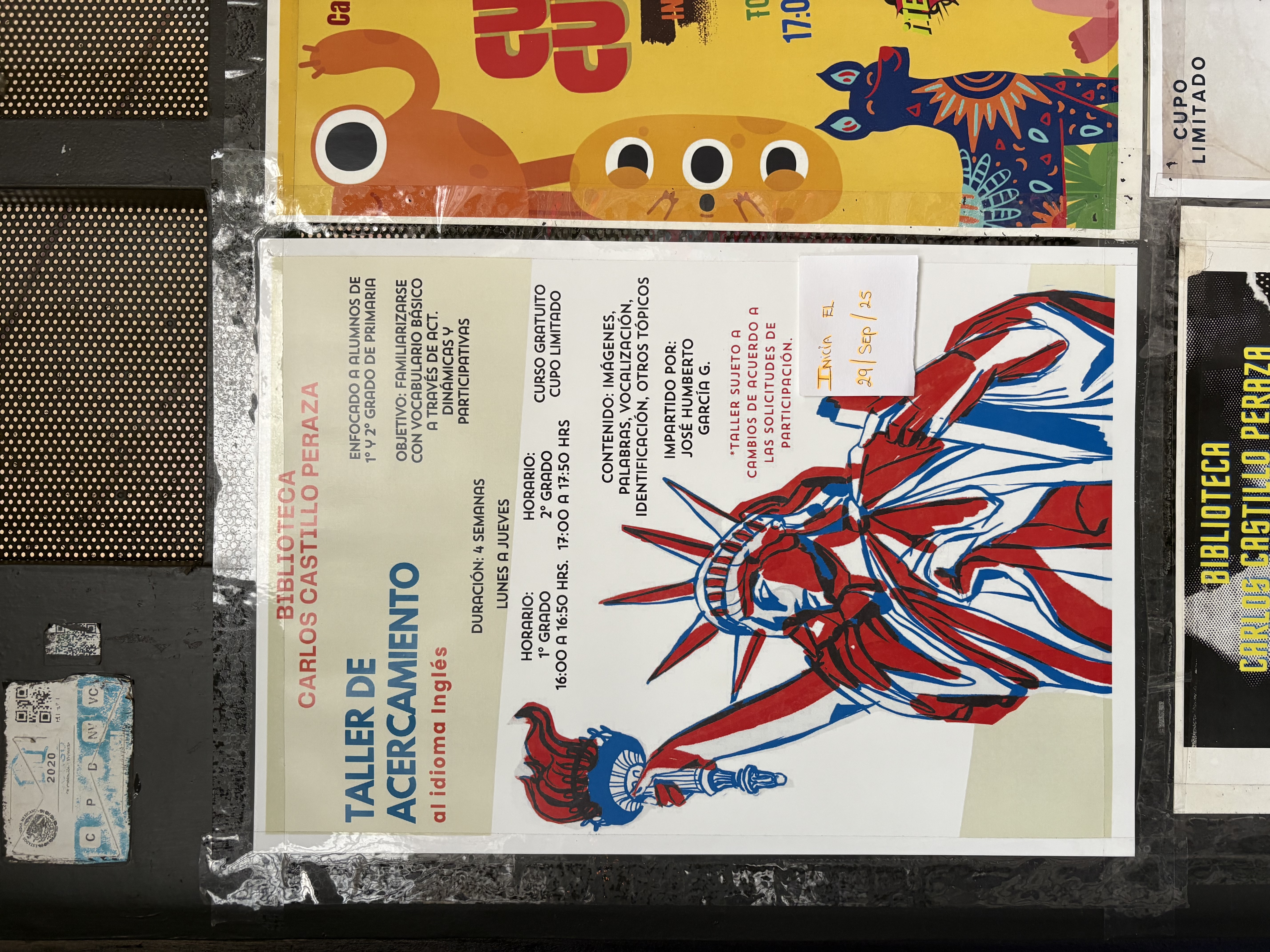

I am in the process of learning a fourth language, after Hebrew and Yiddish. It’s a long story, how I come to be living here in Mexico City, a permanent resident of Mexico, studying Spanish at el Centro de Enseñaza para Extranjeros, composing my clumsy first attempts at writing in Spanish, reading microficciones for my literature class, copretérito, pretérito, the looming subjuntivo, delighted to be learning about sufijos de despetos. The story is as long as the word, “Love.”

Love of course, is gradable in Spanish. In the first few weeks of our romance, I told my girlfriend, “te quiero,” trying to charm her with weak efforts at her own language, hoping she’d long for me as much as she longed for home. Now that we’re married, I upped my game, I say “te amo,” to her and our child. It feels good, to max out love, to be at the very upper limit of the emotion, to have nowhere to go. So when life in the United States took its grim turn, we, in love, married, parents of a beautiful baby, paperwork more or less in order, had somewhere to go. We came back to the city of my wife’s childhood, the monster of her heart, this gran pueblo Tenochtitlán.

I spend almost every day immersing myself in the culture and language of Mexico, trying to understand its moods (my wife’s moods), its politics (those of my wife and our friends being my lodestar), its beauty (the beauty of my wife and child and our family together.) An impossible task, but not necessarily more impossible than what I do in Yiddish, what I did in the Talmud. So why do I hesitate when it comes to the idea of ever translating and publishing a work of Spanish? Why, if I happily use the skills I gained for my family, inherited and spectral, to translate literature, am I unsure I’ll ever use the skills I gained for my family, found and living, for the same?

Here is the volta to Power, the turn of the essay. I feel like stripping back the curtain here, to exposing you to the artificiality of my writing, of my writing you, of this piece that has already thought about languages as love, as connection. It is time to change, to think about raw language, language as particular syntaxes that can only occur here. When I write, how do I write? I write in English. And what is English?

Bastard tongue, virus tongue, all over the world tongue, held at edge of a sword tongue, English forces itself on all of us anglophones, whether that force is the mighty flow of centuries, or, much more usually, real violence done to the heart. The fact is, I speak and write English, fluently, beautifully, and I do so, because generations of my family were humiliated or praised for how they spoke English. An immigrant who barely speaks English, as all but two of my eight great grandparents were, is called “Grine” in Yiddish, sometimes translated to “Greenhorn.” There is a naivety implied, that those in the know (the Americans, the Americanized, like my great grandfather Harry and his wife, my bubbe Rose,) are seasoned wood. Everyone else, green as the spring, brand new, born again into America, where they know nothing.

The shame of that new birth, being told, though you may be an adult, that you are still a child, is actually one of the relatively peaceful ways English has been violently spread. We could talk of colonialism and schools where beating and betrayal is common. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o writes about how in the Kenya of his youth, the British would incentivize children to turn each other in if they heard one another speaking in their native Gikuyu. Education not being sufficient to the task of berating people into losing their languages, we all have heard of or even witnessed confrontations between white supremacist nativists demanding that the people they hear speaking in other languages, “Speak English, this is America!”

And that’s why I wonder if I’ll ever translate Spanish into English. The nature of the relationship between Spanish and English in the moment I live in is not peaceful, not equal. Contempt for Mexicans and their languages is a standard operating hatred of the current white supremacist power structures and government of the United States. A government that continues to collect my tax dollars and spend them on the drug war that ravishes Mexico. A white supremacist power structure that, for the moment, has decided to include white Jews, like me. I don’t agree with these forces or their ideologies, I don’t enact them. But I can’t deny that they raised me and formed me and that I, as much as I loathe them and try to destroy them, represent the world they have created. Moving through the world as a White American, what right do I have to try and resay the words of a brown Mexican poet or writer.

This focus on power analysis is an important lesson of the poet-translator Yilin Wang, whose book, the Lantern and the Night Moths I highly recommend. Wang often posts about their dismay at the amount of people attempting translation of languages of the oppressed global majority with little knowledge of the source language or culture. They particularly dislike the practice of bridge translation, that is, using the “Literal” translation of a usually uncredited translator who DOES know the language, and then those words being “improved” by a monolingual poet or writer. This is probably most famously done by the poet Coleman Barks, whose “translations” of Rumi were heavily criticized in the New Yorker by Razina Ali. We see here behind the mask of “World Literature,” to a world of cultures at war with each other. Or really, several related cultures, those of Europe and the USA, viciously suppressing and twisting the cultures of the world to their own ends.

I began this essay with Ghosts and Love, which may be the only way through this conundrum created by the calcifying nature of power analysis. To break through white supremacy’s insistence on homogenizing culture and language, it may be important to build an ofrenda, to worship the ancestors, to feed them and see what they have to say in turn. This is what I attempted to do in my long learning of Hebrew and Yiddish. This is what I try and do by bringing Yiddish writers to an Anglophone audience. But once it’s done, where does that leave my current life, in Spanish?

I think, if I see a path to translating Spanish, it is a path of relationship. Unlike in Yiddish or Hebrew, where I feel comfortable seeking out works to translate, in Spanish, we will have to see if I can form friendships and working partnerships with Mexican writers. What separates me from the white supremacists who suppress Spanish? Volition? Just wanting to not be them? Rather, I think it is my relationships and love for real people, for seeing the people in my life of any culture or background as people I can love, hold, relate to. That commitment to Humanism is what I can bring to translation that makes it worthwhile.

Readers, what do you think?

With great affection,

Mordecai Martin